Answering the techno-pessimists, Part 1: life expectancy

The techno-pessimists are not our enemies. It’s wrong to think of techno-optimists and techno-pessimists as two opposing teams, each arguing for its own point of view; in fact, we’re on the same side. Both want faster technological progress, we are merely debating how hard the challenge will be. In fact, it’s not even clear that we want substantively different policies.

That said, I’m going to go through a few arguments by TPs and explain why I don’t agree. These arguments are absolutely worth worrying about, and my rebuttals are often more in the form of “here’s why this might be wrong”. But anyway, it helps to think through these issues.

Some of the main TP arguments are (paraphrasing heavily):

We’ve picked the low-hanging fruit of science

Productivity has been slowing down, why should it accelerate now?

Solar, batteries, and other green energy tech isn’t for real

Life expectancy is stagnating

I listed these in order of hardest-to-rebut to easiest-to-rebut. The first one is the most worrying, and the last one is the least worrying. So I’m going to answer them in reverse order. Today, I’ll talk about life expectancy, which is really not a reason to be pessimistic about technological progress.

Is life expectancy stagnating?

The blogger at Applied Divinity Studies posted the following graph:

They write:

So sure, there is a slight uptick, but basically it is still at a plateau with growth far below historical levels.

If you believed in stagnation when the paper first came out, you had better continue believing it in now.

Tyler Cowen and Ben Southwood are not techno-pessimists, but they also made the argument that plateauing U.S. life expectancy is a sign of recent technological stagnation.

But there are two big problems with this argument. First of all, life expectancy hasn’t actually stagnated. Here’s a graph with some other developed nations included:

You can see that the stagnation is almost entirely a U.S.-specific phenomenon. The U.S. falls behind other advanced countries in life expectancy growth around 1980, and absolute life expectancy in the mid-80s, and it never catches back up. It’s also possible that the UK has experienced a stagnation in life expectancy just in the past few years, but too early to tell. The U.S. is really the only one who has clearly plateaued.

Presumably, the U.S. and other developed countries have access to similar life-extending technologies. Thus, the one-country life expectancy stagnation in the U.S. is almost certainly due to non-technological factors — lifestyle differences, differences in the health care system, etc.

Life expectancy isn’t a great measure of technology

First of all, here’s a graph of GDP per capita in England, where they’ve been keeping fairly consistent records for a very long time:

You can see living standards have gone up by a factor of about 30 since the Middle Ages. That reflects massive technological progress. But during that time, life expectancy has increased only by a factor of two:

But in fact, the disconnect between technology and life expectancy is far stronger than even these charts would imply.

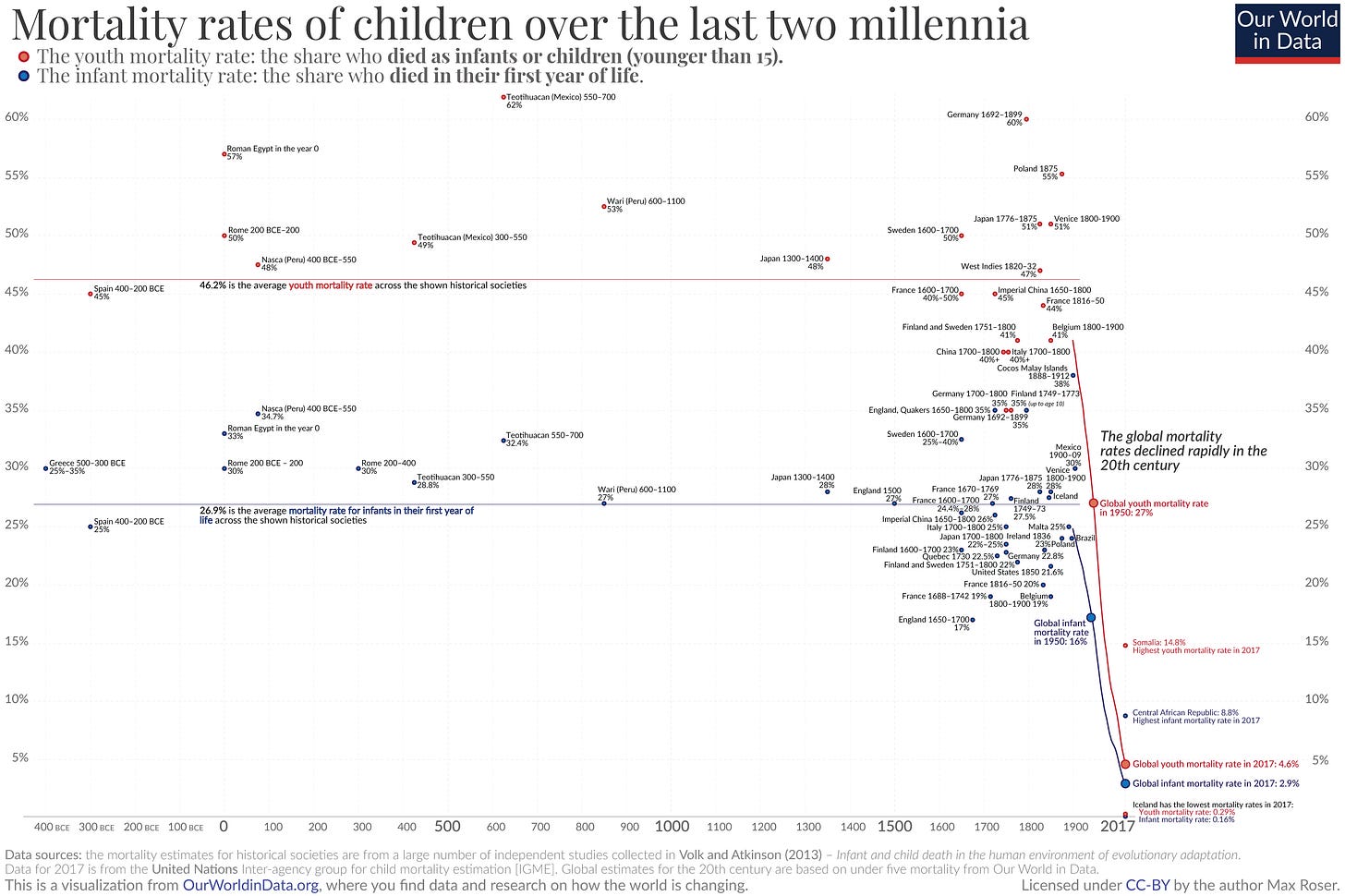

The reason is that much of the big increase in life expectancy was actually a drop in infant mortality (and to a lesser extent, child mortality). We all hear about how people used to only live to age 35 back in Ancient Rome, or whatever. But that’s not right. Basically, if you made it past the danger zone, you could expect to live to age 60 or so.

Now, technologies that reduce infant mortality are very important and very good. These include things like vaccines and antibiotics. But the drop in infant mortality was really a rapid, one-time thing:

Infant mortality rates are really low in developed countries right now, and can’t go much lower. So the contribution to life expectancy from that big one-time drop in infant mortality is over. You can call that technological stagnation if you want, but it really just means “mission accomplished”.

What about the rise in adult life expectancy? Adults used to live to be 60, now they live to be 80. That’s a big improvement!

But when we look at when that improvement happened, it doesn’t really line up with the epic productivity boom of the Industrial Revolution.

For American women, there was a big acceleration between 1930 and 1950 (probably due largely to a big one-time drop in maternal mortality), but otherwise a fairly steady increase that doesn’t really match up with productivity or with our general sense of when the big, important inventions happened.

For men, the big acceleration in adult life expectancy starts around 1970 — basically the exact same point that productivity slowed down! A big driver is probably lifestyle changes, e.g. the drop in smoking:

Anyway, it’s clear that although technology to reduce infant and maternal mortality was very important in giving life expectancy a one-time boost, in general life expectancy is not a good proxy for other broad measures of technological progress.

In conclusion: We might get life extension technology in the future, but we shouldn’t expect a continued steady upward climb of life expectancy as overall technology improves.

So that’s that. In the next post, I’ll address the idea that solar and batteries aren’t a big deal…

By the way, remember that if you like this blog, you can subscribe here! There’s a free email list and a paid subscription too!

I had thought that the ancient life expectancy you describe would apply to men, but that women's life expectancy was much lower due to death from childbirth. One of the modern miracles is the drop in infant/child mortality, but also in reducing the death from childbirth for women. This is an area where the US lags behind and contributes to our lower life expectancy relative to other developed countries.

Generally agree, not deserving of pessimism, but it is difficult to sort out tech impacts here.

Cleaner power and cars will reduce local pollution, providing bankshot health wins. I'm definitely bullish on medical therapies too.

The problem is that behavioral factors can swamp everything else going on. Reductions in smoking, as you mention, contributed a lot to the decline. (Not only in cancer and heart attack rates, but even in things like household fires: https://www.nber.org/papers/w16625 )

In the other direction, that dip a year or so ago was mostly from spiking suicide rates in the mountain west, which doesn't seem to really be a tech story (maybe the lack of mental health tech?) Also, cheap synthetic opiods, which could be called tech working against us.

I'm still holding out for a moonshot on malaria or cancer to improve global health.

Along the way I'm expecting non-health tech to contribute incremental improvements too.

But I still worry the overall trendline will be dominated by behavioral choices, which still need clever new policy solutions in areas where there aren't easy answers.