America doesn't really have a working class

Why class politics is unlikely to succeed where identity politics failed.

In January 2017, I was at a house party in Berkeley. People were discussing why Hillary Clinton had lost to Donald Trump, and one woman — a law student at the University of California — declared that it was because Clinton had ignored the “working class”. I asked her to describe someone in the working class. She imagined a “sex worker” who had a bunch of student loans and a humanities degree that she wasn’t able to use.

This episode really stuck in my mind because of how surprising her response was. I had expected her to describe a unionized auto worker or steelworker or a stereotypical Midwestern guy in a hard hat, and I was prepared to expound on how little of the U.S. private-sector workforce is actually unionized, and how few Americans now work in manufacturing. I was utterly unprepared for her to instead describe someone from her own educated progressive social circles. And yet there it was. To this law student, the “working class” was simply those of her friends who were most down on their luck.

I think about that conversation whenever I hear people talk about how Democrats need to shift from identity politics to class politics. For example, here’s how Bernie Sanders responded to Kamala Harris’ loss to Donald Trump the other night:

Sen. Bernie Sanders…said Democrats lost the 2024 presidential election because they relied too much on talking about race, gender and sexual orientation…Sanders…said Vice President Harris didn’t spend enough time talking about how to help working-class Americans by raising the minimum wage and lowering the cost of health care…

“What were they going to do to address the fact that so many people in America are struggling? Does it have anything to do with the greed of corporate America? The fact that you have a billionaire class that wants it all, they want to own the political system? Does anybody really talk about the degree to which the people on top own this country and want more and more and couldn’t give a damn about ordinary Americans?” he asked.

A lot of Dems and progressives must feel tempted right now to just substitute this kind of class politics for the failed identity politics of the past decade. After all, everyone who remembers 2016 must wonder if Bernie, with his more race-neutral class-focused populism, might have won against Trump. And everyone knows that Dems won lower-income voters and less-educated voters until recently, so it seems like class politics might be able to win them back.

I just don’t think this is going to work.

Yes, I also wonder if Bernie might have beat Trump in 2016. And yes, I think focusing on economic issues — especially ones where Dems have the advantage, like minimum wages and health care — is good. I don’t think it’s sufficient — Biden did a huge amount of pro-worker policy and handed out lots of benefits to lower-income people, and lower-earning voters still abandoned Harris en masse. In a rich country like ours, cultural and social issues often take precedence over pocketbook concerns. But yes, economic appeals are fine and good.

But I think that class politics of the type Bernie is pushing is extremely hard to pull off in America. And I think the discussion I had with that Berkeley law student back in 2017 shows why. Americans simply lack a clear idea of who the “working class” actually is.

If you don’t believe me, look at a poll. It’s common knowledge that most Americans consider themselves “middle class”, but did you know that most Americans also consider themselves “working class”? Check out this poll from earlier this year:

It’s kind of wild that 51% of college-educated Republicans, and 59% of upper-income Republicans, call themselves “working class”. And though the numbers for Democrats are lower, they’re still substantial. Americans just really like thinking of themselves as “working class”, no matter how much money they earn or what degrees they have hanging on their wall.

I could speculate on why this is the case. For many Republicans these days, being “working class” probably just means not identifying with the progressive culture that most highly educated Americans adhere to. Even if you’re rich and have a college degree, you might feel a sense of cultural solidarity with lower-income non-college voters who are turned off or confused by words like “heteronormative” or “cisgender” or “cultural appropriation”. For high-earning or highly-educated Democrats, calling themselves “working class” might simply be a way of saying that they earn their income by working, rather than by collecting passive income from stocks or real estate.

I also suspect that Americans feel that their society is a highly mobile one. John Steinbeck is often (mis)quoted as saying that “socialism never took root in America because the poor see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.” But the flip side of this is that a lot of rich Americans see themselves as recently exalted proletarians. A billionaire might think back to his modest childhood home and think that he’s working class because those were his roots.1

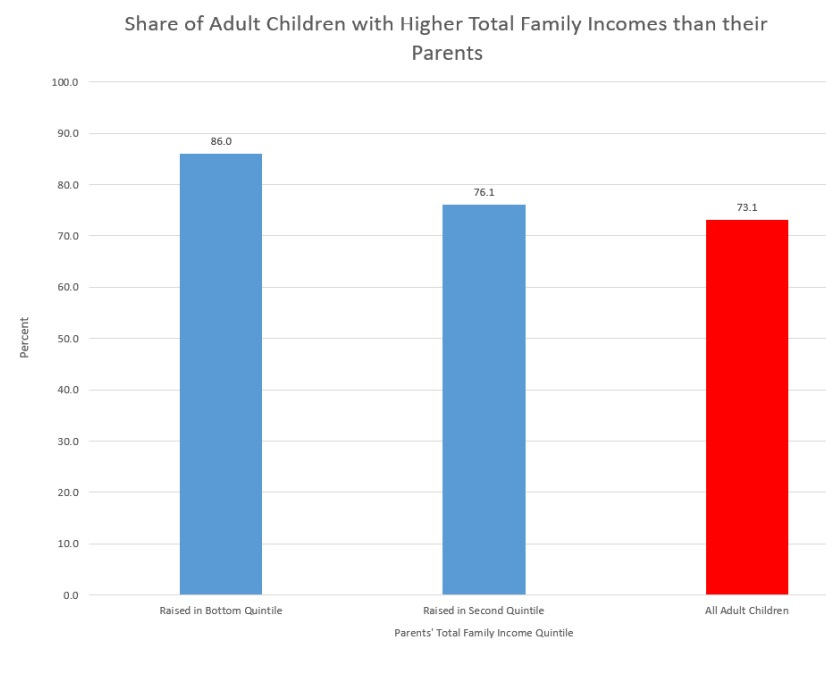

In fact, America is a pretty mobile society. Over the last decade, a lot of commentators, and a few economists, have claimed that the American dream is dead, but the numbers don’t really bear it out. Most lower-income Americans do end up earning more than their parents:

Incomes at the top are especially volatile, and have become more so in recent years. In fact, some research back in 2016 found that 11% of Americans will reach the top 1% at some point in their careers. Across the generations, rags-to-riches stories, and riches-to-rags stories, are not uncommon.

Mobility — including both opportunity and risk/volatility — probably tends to erode the sense of being in a particular socioeconomic class. Before the Industrial Revolution, you had a discrete agricultural class — farmers whose families had always been farmers, and whose children were going to be farmers too. And you had other classes, like artisans or the nobility, who also tended to pass on their occupations, incomes, and social status to their kids. In a post-industrial society, there’s simply a lot less intergenerational persistence.

Of course, the industrial age did famously have the proletarian class — urban factory workers. But in America, that broad grouping has been disappearing, year after year. The vast bulk of the U.S. workforce no longer works in manufacturing2:

In the modern day, Americans’ jobs have simply fragmented too much to form a cohesive class. Service occupations are all over the place — cashiers and baristas, sales assistants and servers, customer service reps and personal trainers, sommeliers and receptionists, medical assistants and warehouse workers, etc. Their jobs don’t necessarily have much in common — probably not enough to form a class-conscious proletariat like in the industrial age.

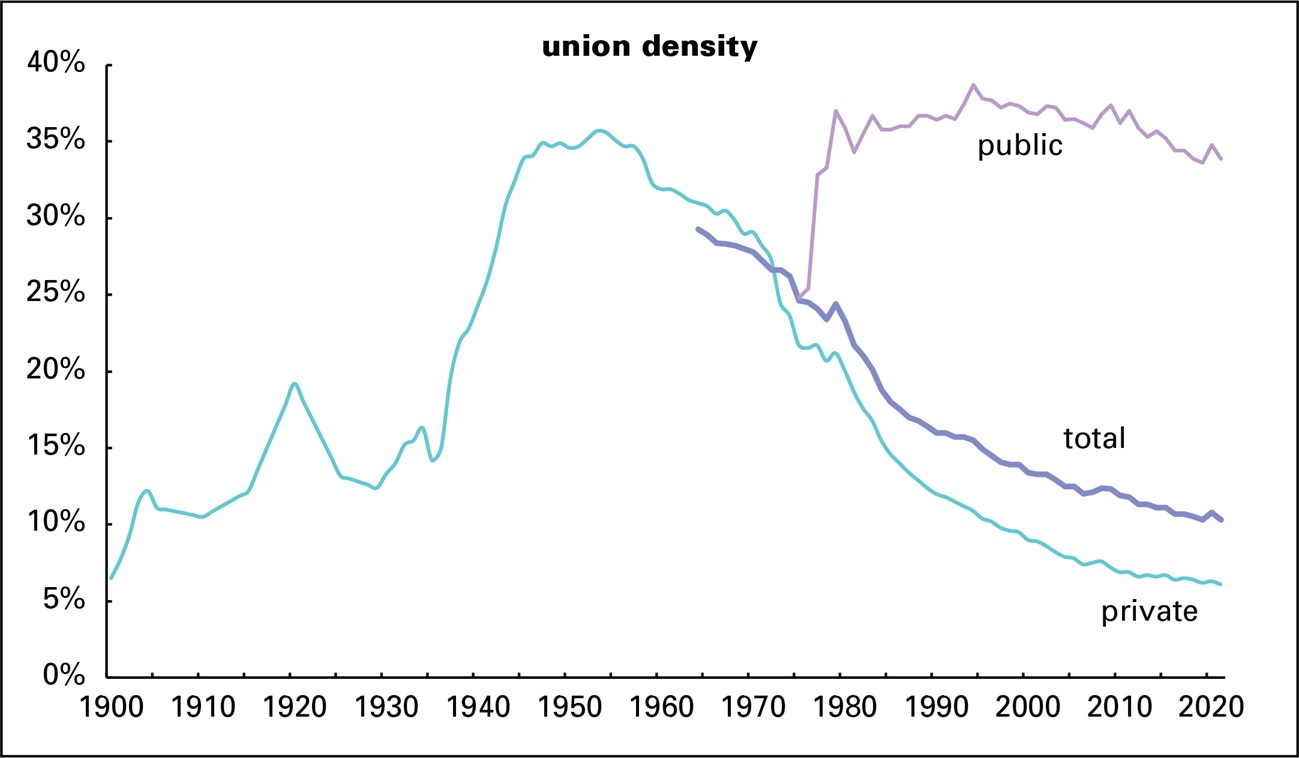

Another thing that defined the American “working class” in the mid 20th century was unionization. But private-sector unionization has declined to almost nothing in America:

As you might expect, the fall-off in private-sector unionization, coupled with still-high public-sector unionization, means that union workers are now a lot more educated than they used to be. Farber et al. (2018) show that in the postwar period, union workers in America tended to be significantly less educated than other workers, but that this is no longer true.

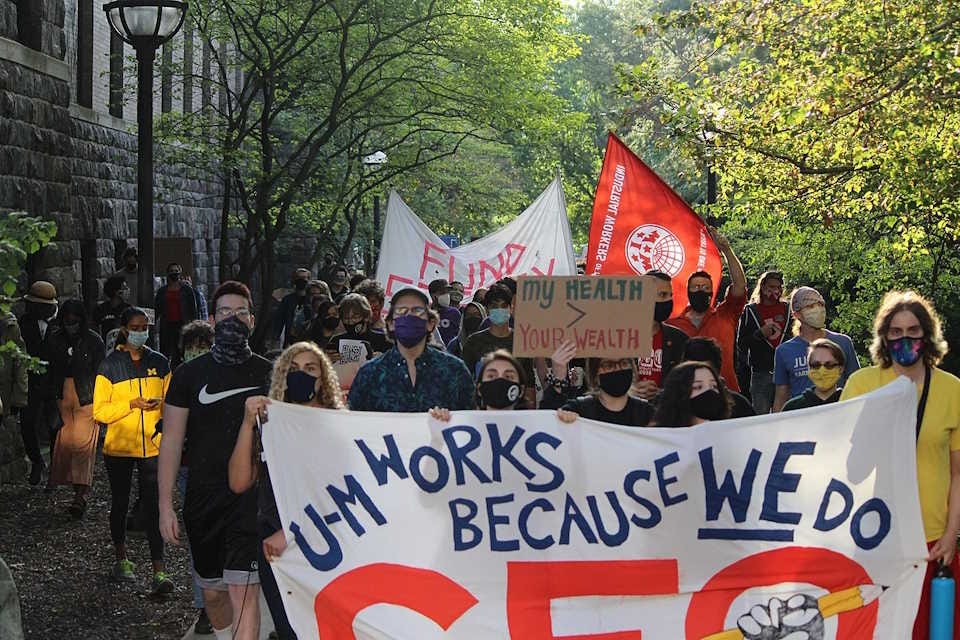

Just to give you one example, I was a union worker! As a grad student teaching economics classes at the University of Michigan, I was in a union, the GEO. I even went on strike with that union, much like the people in the photo at the top of this post.3 But despite this experience, I never felt I was part of the same social class as the unionized factory workers of the 1950s. Far from it.

This might be why when Joe Biden became the first sitting President to walk a picket line, the number of people who identified with his action was fairly small. The typical unionized worker is no longer a blue-collar swing voter who works on an assembly line, but a government employee who’s likely to vote for the Democrats already.

What about dividing the economy into people who work for a living and those who collect passive income? There’s certainly a lot of capital income out there, and rich people own most of the stocks. But our numbers for capital income are probably greatly exaggerated, because capital income gets taxed at a lower rate than labor income. Smith et al. (2019) find that most rich Americans get a lot of their income from working at their own pass-through businesses, but classify most of this as business income in order to pay a lower tax rate:

A primary source of top income is private “pass-through” business profit, which can include entrepreneurial labor income for tax reasons…Tax data linking 11 million firms to their owners show that top pass-through profit accrues to working age owners of closely held mid-market firms in skill-intensive industries. Passthrough profit falls by three-quarters after owner retirement or premature death. Classifying three-quarters of pass-through profit as human capital income, we find that the typical top earner derives most of her income from human capital, not financial capital.

(And yes, this means that the decline in labor’s share of income is probably significantly exaggerated. The story is probably more about labor income inequality than about passive capital owners taking a larger share.)

So almost all Americans are putting in a lot of hours on a day-to-day basis. Yes, some do backbreaking manual labor and some write emails. There is still a divide between blue-collar and white-collar work. But so many Americans now do white-collar work that we seem to have collectively decided that it too constitutes “real work” — that as long as you put in the hours, you’re working. And so there’s very little divide between workers and non-workers in America.

What about just defining “working class” by income? For all the talk of the working class vs. the professional class, there’s not actually a discrete divide between these groups in the data. It’s actually just a continuous distribution:

If there were multiple peaks in this distribution, you could identify them as discrete “classes”, but since there’s only one peak, the difference between the “classes” on this chart is just going to be a series of arbitrary cutoffs. As a commentator, you can just decide to call everyone in the bottom third of the distribution “working class”, everyone in the middle third “middle class”, and so on. But will people in those “classes” really feel any sense of solidarity with each other?

I doubt it. Suppose the cutoff between the “working class” and “middle class” on your chart is at $40,000. My bet is that someone making $39,000 will identify more closely with someone making $41,000 than with someone making $12,000. A continuous distribution just doesn’t lend itself to “classes”.

In fact, the only real class distinction in America that I think makes any sense is higher education. Whether you go to college makes a huge difference in your life — both in terms of future income and the kind of jobs available to you, and also in terms of health and other social outcomes. This is why I do think it makes sense to talk about an “educated professional class” in America:

But just because America’s educated professional class has a fairly unified culture doesn’t mean that the people who didn’t go to college have any kind of working-class solidarity or class consciousness. College is a powerful integrating institution — it instills a certain culture and certain attitudes in the people who go there, and it teaches them to behave like a single community. But the Americans who don’t go to college mostly don’t have anything like that, unless they join the military or are very religious. Instead, the non-college “class” is highly fragmented and isolated. We can call them “working class” if we want, but that doesn’t mean they’ll behave like one, or care when Bernie gives them a shoutout.

A postindustrial economy like America’s has a whole lot of workers, but no real working class. That’s why if Democrats want to win back lower-earning and non-college voters, I think they’ll have to appeal to them as Americans, rather than as one side of a class struggle. Bernie Sanders’ class politics may have felt like a refreshing alternative to racial identitarianism back in 2016, but they’re really something out of another age.

Therefore I think that while Democrats should definitely address pocketbook issues, the idea that lower-earning and non-college Americans can be motivated to rise up against the rich with some combination of pro-union policy, more health care subsidies, higher minimum wage, and fiery rhetoric against billionaires is probably fanciful. As much as people might like class war to be an easy off-the-shelf substitute for identity politics, it’s unlikely to be any more successful.

Even if his roots were actually middle- or upper-middle-class, he might see that living standard as “working class” in retrospect, because it’s so much lower than what he enjoys today.

Some of this decline is actually exaggerated by outsourcing. In earlier decades, manufacturing companies would also do a lot of their own business services — accounting, payroll, and so on. The employees who did those things were counted as manufacturing employees, because they worked for companies that were classified as manufacturing companies. Now, manufacturers largely outsource those functions to businesses that specialize in those services, so the people who do those services are no longer counted as “manufacturing” workers. Still, the number of people who actually work in factories has definitely declined enormously as a percent of the total workforce.

We ultimately succeeded in getting better health benefits and various other benefits that I now forget. I did think striking was a bit silly, since we were all going to have high-paying jobs in the future. But I did it anyway, because, well, it was fun, and I was in my 20s. I like to think I was a little more ironic and self-aware about my working-class LARPing than some of my fellow grad students.

If you want to get a definition of working class, maybe you asked very much the wrong person? Because your description seems to come from someone who has never actually talked to a blue collar worker.

I live in a very red area, moved out here because I wanted to live in an area where keeping horses was feasible. Don’t have horses any more but I am still here. I have lived here for a good while. What I see with people out here who consider themselves working class:

Most are NOT in a union, by a large margin.

Many are self-employed or employed by very small businesses, including plumbers, electricians, carpenters, pest control, grading companies, landscape companies, fencing companies, mechanics, welders

Others are police or firemen

Most are loosely associated with some type of house of worship, men often more through their spouses than personally, and they are respectful of religion even if not devout

Income levels are not the determining factor in what class they perceive themselves. Working with their hands and having a small business are. Some are out and out wealthy.

They are very attached to their specific community with ties of friendship and family and are not interested in moving for more income

Their safety net tends to be family and community resources rather than public programs

They often have outdoors oriented interests and hobbies that are negatively impacted by density, including hunting, fishing, camping, small scale agriculture, the last often on land long time owned by their family

Finally, yes, they have a very definite feeling of class consciousness, but it’s not at all an academic definition of class. That class consciousness is reflected in the music they enjoy, the movies and TV they choose, the comedians they find funny, and, more on point, the politicians they elect.

Policies targeted at unions and green energy thus don’t benefit most of the people I know who consider themselves working class. That’s probably why they are not moving the needle.

FWIW.

Re the point that income (and wealth for that matter) is a continuous distribution - I think this is why the Occupy-era notion of "the 99%" never really took off. That's an insane way to divide up the population - there is no way in which people at the 1st and 98th percentiles of affluence have anything like the same material interests.