Zines!

An old underground culture quietly thrives.

“I wanna publish zines/ And rage against machines/ I wanna pierce my tongue, it doesn’t hurt, it feels fine” — Harvey Danger

The news is pretty brutal these days, so I thought I’d take a quick break to do another subculture post! It’s been a while since I did one of these. The first two can be found here:

Today’s post is about zine culture.

“Zine” is short for “magazine” or “fanzine”; the term was coined in the mid 20th century. Before the internet, the main way to disseminate writing and images was by printing it out on paper. Printing presses are expensive, and a fleet of trucks to distribute your publication is even more expensive, so the flow of information at the national level tended to be pretty concentrated in the hands of a few big players. If you wanted people to read what you wrote and you didn’t have a ton of capital behind you, you were reduced to guerrilla methods — using a photocopier and hand-distributing your writings, drawings, or photos in small batches.

And this is exactly what zine makers did. If you were part of a fandom that had only a few other adherents — a sci-fi show, or a rock band, etc. — then zines were a cheap and fun way to reach the few other people out there who liked the same things you did. If you were an underground artist, zines were a great way to start building a fandom from the ground up. And if you were someone with subversive or radical ideas that mainstream media refused to acknowledge, you could use zines to expose people to those ideas.

But zines really found their footing in the 1970s and 1980s, with the explosion of punk zine culture. Molly Tie has a very good article covering this history, if you want to read more about it. Photocopiers improved and copy shops opened everywhere, making it much easier to print off big batches of zines. At the same time, punk culture and queer culture combined music fandom, alternative lifestyles, and radical politics into one relatively unified whole, which greatly increased the audience sizes for zines with these themes.

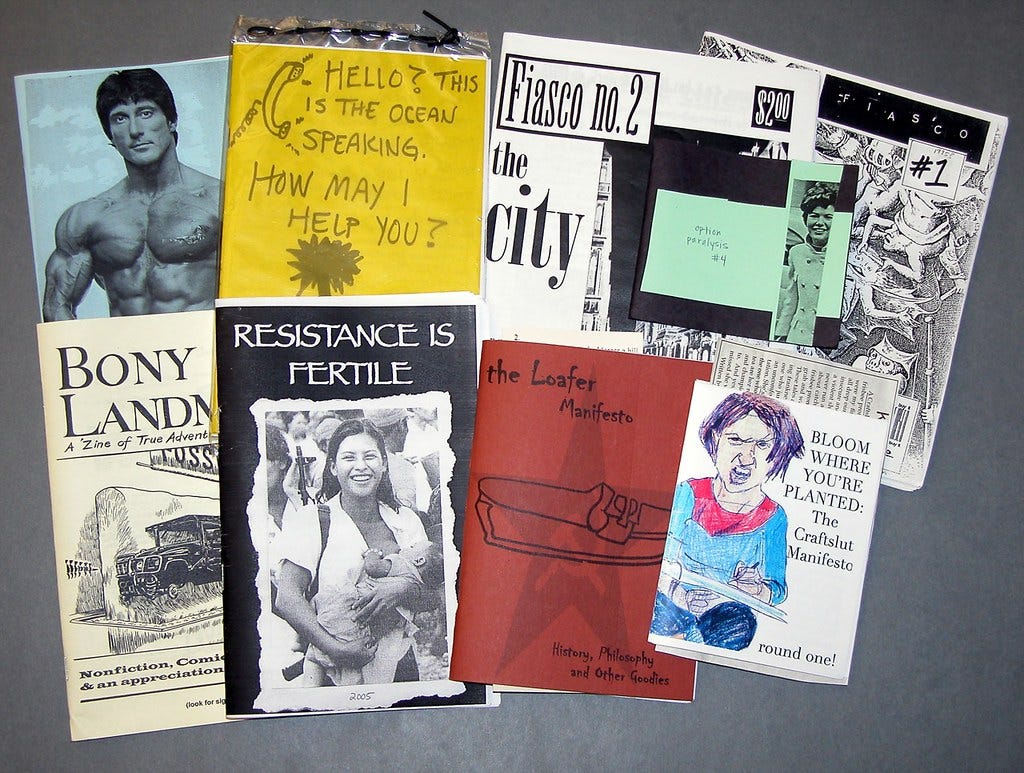

Libraries have done an amazing job of preserving zines from this golden age in all their glory. If you have a day or two to spare, you could do worse than to spend a day at your local library, curled up in the stacks immersing yourself in underground cultural history:

In fact, zine fairs were one of the things that exposed me to punk culture, way back in the early 2000s. By then, of course, the internet was already starting to replace zines. It’s even easier to put your stuff on a website as it is to print it out on paper, and more importantly it’s far easier to distribute it. Instead of going to zine fairs and selling your work in small batches to passers-by or giving your zines to a music store to set out by the cash register, you can blast your writings and drawings out to billions of people all over the world. Social media like Instagram, of course, makes this even easier.

And even more fundamentally, the internet makes it much easier to accomplish the basic functions that zines were created to accomplish — finding like-minded people, disseminating ideas, and building a fandom. Social media has made zines irrelevant for many purposes, and as a result, physical zine culture has waned over time.

Waned, but not disappeared.

The persistence of zines in the online age

There’s something satisfying about holding a physical zine in your hands that even e-readers and tablets will never replace. That’s why the demand for physical comics, for example, has remained strong. Physical zines remain an important way for up-and-coming comics artists to get practice, to build a small core fandom, and to create a portfolio of work. Thus, zine culture has increasingly merged with indie comics culture, to the point where it’s not even clear there’s a meaningful distinction between the two.

But comics aren’t the only zines left. Indie photographers, sketch artists, and poets also still find it useful to have a portfolio of physical work, though perhaps to a lesser degree than comics artists. “News” or op-ed zines have seen the biggest shift to online-only.

Meanwhile, there are a lot of people who make zines just as a fun hobby, just to make something fun or to honor a traditional art form, without any greater purpose. And there are people like me who enjoy consuming physical zines of any type, partly for the nostalgia, but partly because there’s just something special and unique about the chaotic, information-dense format that paper zines create. Like string orchestras, zines are an art form that I suspect will never vanish. Of course there are also plenty of e-zines, and these are part of the culture too.

Physical zine culture also creates something that online culture finds it difficult to create — community exclusivity. The activation energy of showing up regularly to zine fairs and indie comics stores is much higher than for joining Facebook groups or posting on Instagram pages. Online communities are always struggling with random people who come in either looking to disrupt and troll, pretending to be fans, or simply not knowing what they’re talking about. This dilutes the community. Physical spaces, in contrast, create a more exclusive community simply by isolating the people who care enough to show up IRL. That can create a safe space in terms of ideology or identity, or it can just allow hardcore fans to associate with other people who are familiar with all the same esoterica.

The internet makes it easy to find your people, but very hard to be around only your people. That’s why in an age when everyone is online, zine culture has managed to stay rebellious by resolutely maintaining an offline component.

The San Francisco Bay Area has always been a hotbed of punk culture and queer culture, so it’s naturally one of the remaining bastions of zine culture. San Francisco Zine Fest is now online-only due to the pandemic, but in normal years it’s an amazing place to shop for zines, meet creators, and just hobnob with other fans. East Bay Alternative Book and Zine Fest has also mostly shifted online, though they continue to do smaller in-person events around town. Hopefully these events will go back to being in-person, because they’re truly excellent.

In the meantime, the best place to get zines, and to meet creators and fans, is indie comic stores. My two favorite places to get zines are 1) Silver Sprocket, an indie publisher that also has its own bookstore on Valencia St. in the Mission, and 2) Bound Together, an anarchist collective bookstore on Haight. I’d definitely start with one of those if you want to try out some zines. Two other places are Needles & Pens, whose store may have moved recently, and Comix Experience on Divisadero.

But what’s actually in zines these days? I thought I’d share a few samples of zines that I’ve read in the last couple of years, so that you can get a good general idea. (In fact, this whole post was prompted by me discovering a bag of unread zines and going through them.)

A longing for intimacy and community

The first example of a zine is just called Hug, and is just a series of photos of people hugging each other. (This is the zine pictured at the top of this post.) I don’t even know who it’s by; there’s no author or publisher listed. Somehow that felt emblematic of zine culture to me — a celebration of intimacy that has to be earned, a community that you can’t simply navigate to in your web browser and enjoy for a weekend. More generally, though, Hug feels like a celebration of “Found Family” — the idea that friends can become as close as family. And of course, because subcultures are places to meet friends, they’re important tools to create intimacy in an age when all the institutions of society — jobs, suburbia, the toxicity of social media — seem to be pushing us toward disconnect.

A yearning for intimacy is probably the most common single theme I see in zines and indie comics these days. How to Stay Together Forever, by Krusty Wheatfield and V Vale, is a how-to manual on long-term relationships. Here’s a page from that:

In fact, a number of zines I’ve read in recent years feel like a cry for understanding and acceptance — if not by people’s actual families, then by broader society, and especially by their Found Families. A lot of zines I see these days are forthright explanations of what it’s like to have cancer, or depression, or be asexual and Black, etc. — the kind of thing that might make someone feel vulnerable or exhausted to have to explain in person, but which they still desperately need other people to understand. For example, here’s a page from a series of zines called Please Tell Me More About Myself:

And here’s an excerpt from NOW WHAT?, a zine by Roman Ruddick about what it’s like to have cancer:

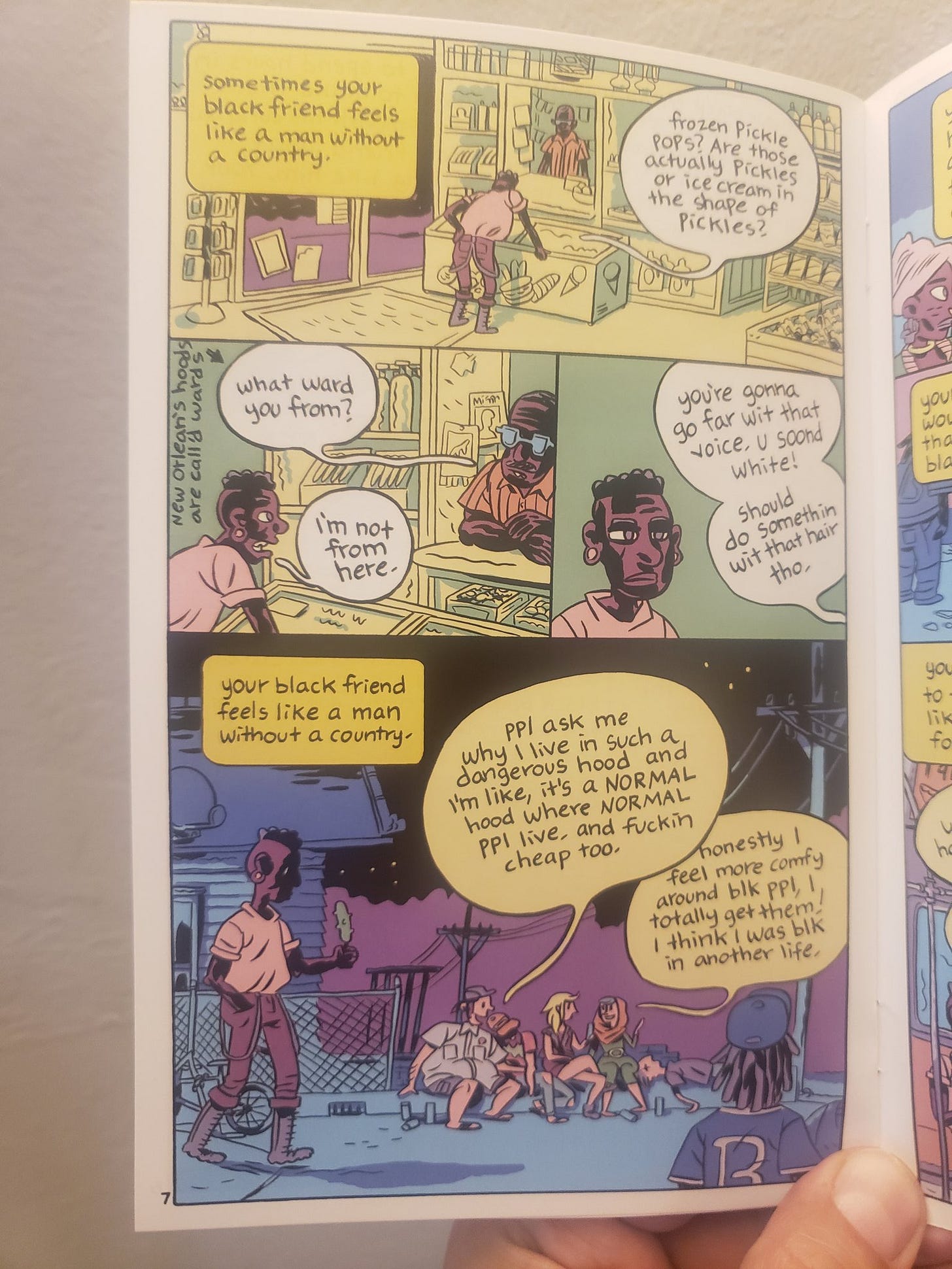

Indie comics can do a similar thing, though often less explicitly autobiographical. The best example of this I’ve read in recent years is Ben Passmore’s Your Black Friend, which got very famous in 2016 and sold over half a million copies, becoming a breakout hit of the early BLM era. Here’s a page I found particularly powerful:

Some of the “personal explanation” zines are more oblique, telling someone’s story through anecdotes and pictures rather than straightforward explanation. A particularly beautiful example of this is Jenell Del Cid’s Memories Are Ghosts:

Some zines, instead of explaining a particular identity or lifestyle, simply imagine a world where it’s the norm instead of the exception. One example here is Welcome to the Neoworld, by @linhtropy. A few years ago when Blade Runner 2049 and the TV adaptation of Altered Carbon came out, a number of people complained that cyberpunk was stagnant — too focused on 1980s retrofuturist aesthetics, too white and male, and so on. Welcome to the Neoworld was part of that wave; it lists a bunch of hypothetical cyberpunk characters who are nonwhite, who have pronouns like “ze/zir/zirs” and “xe/xem/xir”, and who list identities like “trans genderfuck f3mm3” and “aroace”. Here’s a page:

If you’re new to woke culture, or not a fan of it, this might be hard to take in. But I’m not new to it, and while bingeing on recent zines I noticed something beyond the abundance of pronouns and gender identities and such. There’s not much political in here. Even when political acts are advocated or glorified (for example, an anti-police protest), it’s generally portrayed as an act of personal expression rather than a plan for change.

Of course, you could retort that the personal is political, and that simply creating social spaces where “xe/xem/xir” is normal is itself a political or even revolutionary act. To me, though, this seems like a semantic difference that obscures more than it reveals. The zines I’m reading these days are remarkably inward-focused — either on the individual and their struggles and identities, or on a (real or imagined) small community.

We can talk about this as some feature of contemporary society — a reaction to the loneliness and alienation of the Instagram-and-suburbia age, ideologies as the consumer goods of late capitalism, and so on. Conservatives will doubtless snort at this stuff as the identity-obsessed narcissism of the snowflake generation. But when I read zines like this, I think less about social trends and more about the timeless power of subcultures.

One magical thing about subcultures is that they can embody the fantasies they dream about. In my post about weebs, I theorized that weeb culture is a real-life space where people can be as romantic as the characters in an anime show. Zine culture isn’t quite as immersive as weeb culture, but in a way it does a similar thing for family. You can come out to San Francisco and write a zine telling the world all the things you’d like to tell your family, and maybe a Found Family will hear you. The world may never turn into a cyberpunk Neoworld populated by genderfuck transf3mm3 artists in fancy chrome outfits, but Bay Area zine culture is already there. Your mileage may vary, but personally, I think that’s beautiful.

No, this is not the zine culture of 1985. It’s smaller, quieter. The locus of spontaneous weirdness and radical politics and hipster fandom has moved online. But somewhere, zine culture still lives, and still thrives.

P.S.: It didn’t fit with the larger theme of the post, but I did want to show one zine that displayed the kind of punk energy I enjoyed in the early 2000s. Here’s a page from my favorite issue of Mission Mini-Comix. It’s my favorite issue because it raves about inflation, almost the way an angry conservative suburbanite would do, but manages to keep it leftist by presenting inflation as a conspiracy by The Man and a symptom of a “Dying Empire”.

Zines and small presses were how we found out about non-mainstream stuff pre-internet. Today any goofball can find sh** on the internet and go down deep into crazy-land. Back then, you had to really work at it! And it was fun!

Brings me back to my days as an 80s punk. I had a few friends who tried their hand at making a few. They used to be left at Middle Earth Records in my hometown of Downey, Ca.