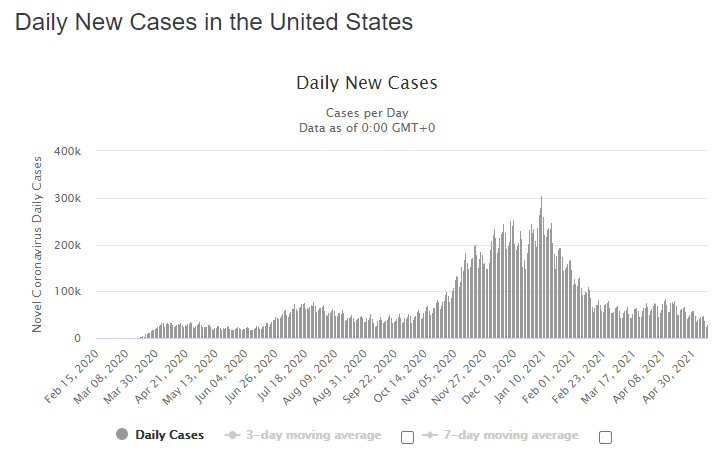

Back in the early days of the pandemic, I started a public interest website called TestAndTrace.com. Our goal was to encourage and to help state governments implement contact tracing programs to contain the virus. After a few months it became apparent that we had failed in our mission, for two main reasons. First, U.S. testing mostly relied on companies that sent their tests to centralized distribution centers, which took several days to turn tests around — far too long to catch people before they spread the virus (this has improved hugely in recent months). Second, and even more importantly, unlike many countries in Europe and Asia, the U.S. never managed to suppress the spread of the virus to low enough levels.

If you can never suppress the virus, your cases never get low enough where contact tracing is able to isolate them.

Before we had vaccines, the main tool we had for suppressing the virus was government-mandated social distancing restrictions — also known as “lockdowns”. In practice our restrictions weren’t anything like the draconian lockdowns China implemented, where people were literally sealed inside their houses. But many European did manage to use government-mandated distancing to suppress the virus…at least until the variants arrived at the end of 2020.

Had we managed to do the same, we might have saved a lot of lives, even if fast-spreading variants and distancing fatigue eventually defeated us in the fall. The reason is that in the early days of the pandemic, we didn’t know how to treat COVID, and death rates were pretty high — maybe about 1% of those who got infected, and around 1 out of 5 people who were hospitalized. By the end of the pandemic, as we learned how to use things like steroids and oxygen to keep people alive, death rates fell to less than half of that level. If “lockdowns” had been able to suppress the virus in the U.S. like they did in Germany, a lot of Americans would still be alive today.

Lockdowns were a very contentious topic. Most of the opposition came from the political Right; small businesspeople were worried about losing their livelihood, and some well-to-do folks were worried about a once-in-a-century pandemic getting in the way of a nice night out:

On the Left, many supported lockdowns, except when it came to protests (fortunately we lucked out when outdoor spread turned out to be very rare). And governors of “blue” states like California and New York were obviously anxious to minimize lockdowns in order to protect their economies (which actually doesn’t work, for reasons we’ll get to in a bit). Meanwhile, let’s not even talk about the debate over remote schools — some topics are too contentious even for this blog.

So anyway, Americans generally resisted lockdowns. And mobility data show that Americans didn’t even really follow the weak, patchy, and temporary lockdowns we put in place.

So this entire post is a moot point. Lockdowns failed. A bunch of us died, until eventually we got vaccines. This post doesn’t really matter at all. But now that the evidence is in, I feel a strange desire to set the record straight.

The evidence that lockdowns work

There is copious evidence that lockdowns reduced transmission of the coronavirus. Some types of social distancing restrictions are more effective than others, and some sub-populations benefit more than others, but overall, lockdowns did limit the spread and saved lives.

That’s hardly a surprising result. The bigger question is, what did lockdown do to the economy? Most people make the natural assumption that lockdown hurts the economy — if you ban people from going out to restaurants, that stops people from spending money on restaurants, right? Obviously. Many economists made this assumption when they tried to model pandemic policy. In fact, some people go so far as to blame all the economic costs of the pandemic on lockdowns:

If you think something seems fishy about that claim, you’re right. The fact is, even without lockdowns, plenty of people will avoid restaurants and other crowded spaces during a pandemic simply out of fear of catching the virus. And that will hurt the economy.

And lo and behold, when we look at evidence, we find that lockdowns accounted for only a small percent of the economic slowdown. For example, economists Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson looked at the state border between Illinois and Iowa. On the Illinois side, the towns issued stay-at-home orders, whereas on the Iowa side they did not. And guess what — economic activity fell almost as much on the Iowa side as on the Illinois side!

This is very similar to the results of a comparison of Sweden and Denmark. Denmark locked down and saw its economic activity decline by 29%; Sweden chose not to lock down, and saw its economic activity decline by 25%. The biggest economic destroyer by far was not government policy; it was fear of COVID.

In fact, states that didn’t issue stay-at-home orders in the spring of 2020 saw just about the same amount of economic devastation as states that did issue those orders:

And a paper by Eliza Forsythe, Lisa B. Kahn, Fabian Lange and David G. Wiczer from April 2020 looked at various sources of data on employment levels, and concluded:

To a first approximation, this [employment] collapse was broad based, hitting all U.S. states, regardless of the timing of stay-at-home policies…Nearly all industries and occupations saw contraction in postings and spikes in UI claims, with little difference depending on whether they are deemed essential and whether they have work-from-home capability…This set of facts suggests the economic collapse was not caused solely by the stay-at-home orders, and is therefore unlikely to be undone simply by lifting them.

The other piece of evidence that lockdown didn’t hurt the economy much is the timing. For example, people stopped going to restaurants well before lockdowns were implemented. Meanwhile, a recent analysis by Chetty et al. looked at very detailed data on business activity and employment and found that “State-ordered reopenings of economies had small impacts on spending and employment.” Here are some pictures:

You can’t even see the effect of lockdowns at all! It’s all just fear of the virus itself.

How did lockdowns save lives without hurting the economy?

At this point you may be scratching your head (or, if you’re a lockdown hater, seething with rage). How the heck could lockdowns have a big effect on the transmission of the virus, but only a small effect on the economy? Shouldn’t the tradeoff basically be one for one? Doesn’t every infection you stop mean one less meal in a restaurant, one less drink at the bar, one less trip to the store, etc.?

Well, no. That’s not how it works. As the evidence above shows, it’s fear of the virus that was the big economic killer. And if fear is proportional to actual infection rates, then by suppressing the virus, lockdowns reduced fear.

Let’s do a little thought experiment. Suppose in City A, they lock down. People stay home. The economy gets hurt, but the virus gets suppressed and infections go to a low level. Eventually, they can start to reopen safely, and they don’t immediately get another wave of COVID because there just aren’t that many sick people in town. But in City B, they don’t lock down. 80% of people stay home because of fear, so the economy gets clobbered anyway. But the 20% who go out end up spreading the virus, raising the infection rate to a high level. That causes more fear, and eventually even the 20% who were going out get scared enough to stay home. But now it’s too late — infection has a higher baseline, and takes much longer to go down. So the fear lasts longer, and so does the economic pain.

In fact, this is why in the long run, lockdowns might even have helped the economy. Countries that don’t lock down will have higher infection rates, thus prolonging the fear and keeping people in their house for longer (on top of having to pay higher medical costs). In its World Economic Outlook in October 2020, the IMF notes this possibility:

The effectiveness of lockdowns in reducing infections suggests that lockdowns may pave the way to a faster economic recovery if they succeed in containing the epidemic and thus limit the extent of voluntary social distancing. Therefore, the short-term economic costs of lockdowns could be compensated by stronger medium-term growth, possibly leading to positive overall effects on the economy.

And an analysis by some folks at the Institute for New Economic Thinking found that countries that tried to sacrifice lives to save their economies ended up hurting their economies anyway.

In fact, historical evidence shows that something very similar happened in the Spanish Flu, the eerily similar pandemic that hit us almost exactly 100 years ago. A March 2020 study by economists Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner found that cities that enacted stricter social distancing restrictions in response to the Spanish Flu saw their economies recover faster.

In other words, we were warned. This isn’t just a case of — pardon the pun — 20/20 hindsight.

The Swedish Experiment

But nothing illustrates the benefit of lockdowns better than the case of Sweden. Sweden famously refused to lock down, while its Scandinavian neighbors did. How did that work out? Here are the final results in terms of deaths:

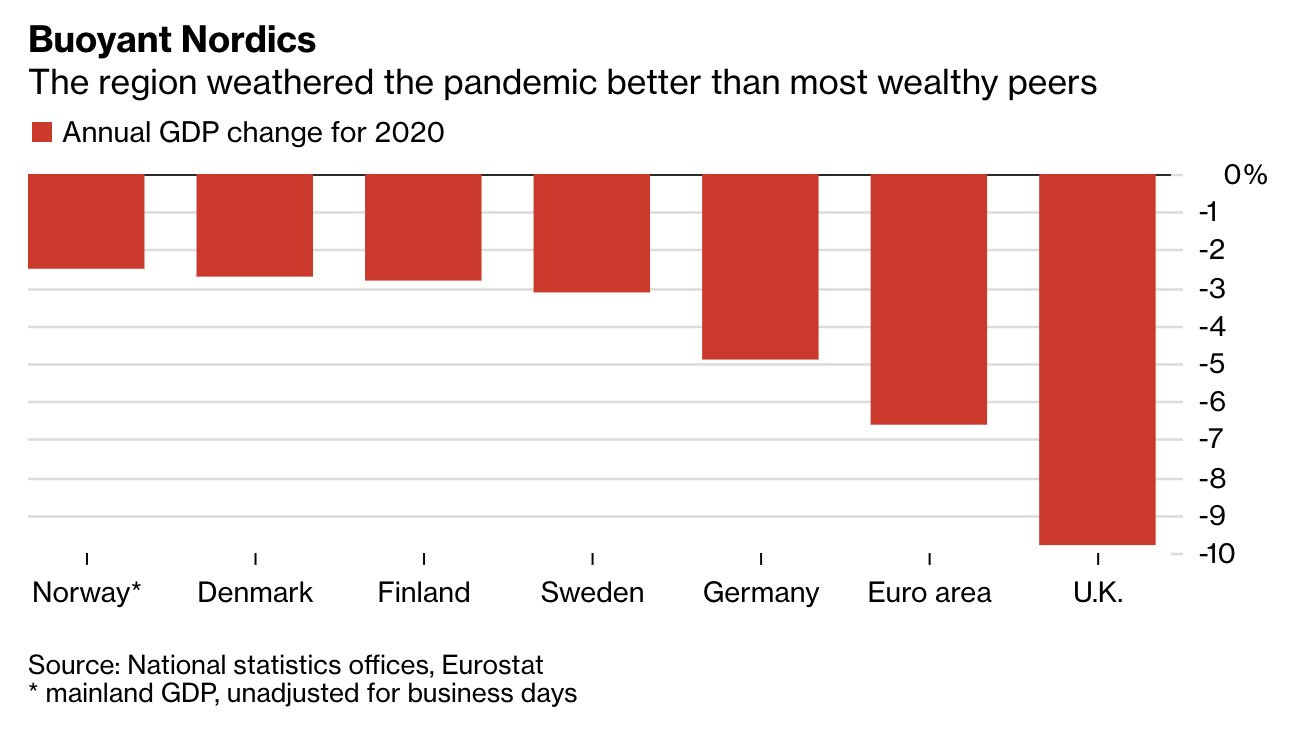

And here, via Alec Stapp and Eurostat, are the economic numbers:

So while Sweden’s economy did better than most Euro area economies, it did worse than those of its Scandinavian neighbors who locked down. Denmark, Norway, and Finland are the most similar countries to Sweden both geographically and culturally, and their lockdowns managed to save lives while also probably improving economic performance a bit.

In other words, the Swedish experiment failed. Lockdowns were good.

Who cares?

Yes, this is all a moot point now. The pandemic is receding rapidly, lockdowns are basically over, and I am a bitter, defeated man shouting at clouds.

But there’s a lesson here for us to learn, should we choose to do so. The reflexive framing of policy as a choice between human lives and dollars of GDP is often a false one; in the end, the economy is made up of human beings, and valuing those human beings is pretty much the best thing you can do for your economy.

It’s not a moot point. Worldwide COVID cases are still at near-record highs. Many Asian countries which had previously been doing quite well (e.g. Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand) are experinecing spikes and have to decide what to do now. E.g. Taiwan is currently reporting several hundred cases a day of B.1.1.7 with less than <1% of the population being even partially vaccinated and now has to decide what sorts of restrictions to enact, for how long, and what the goal should be.

I can agree with Noah on this topic. Australia has practiced severe lock-downs whenever the virus shows up.......and the government has funded the resulting economic pain with an (initially at least) generous wages supplement for idled ("non-essential") workers.

Yet Australia's economy has performed relatively well, suffering only one quarter of negative growth, and now back to c.5.5% unemployment, (from a high of c.10% at the beginning of the pandemic). Needless to say, Australia's vaccination program is progressing at a very leisurely rate.

But note, I'm an MMTer. The whole globe's non-essential economy should have been locked down and managed with IMS and BIS money printing.....I reckon 3 million lives could have been saved (ignoring, for the sake of the argument, the negative effects on some families being cooped-up with one another for an extended period of time..)