Why would Pakistan grow?

Its political system apparently gives it little reason to invest for the future.

I recently wrote a post about Bangladesh’s startling and encouraging economic growth. A number of people have asked me to write a follow-up post about Pakistan, so here it is.

In terms of growth, Pakistan is lagging its neighbors badly. In purchasing power parity terms — the best measure for comparing individual living standards, though hardly perfect — it was passed by India in 2010. It’s still a bit ahead of Bangladesh, but the gap is closing. Since 1990, both of those countries have outgrown Pakistan by quite a bit:

In nominal terms — which are a better reflection of international purchasing power — Pakistan fell behind Bangladesh in 2018:

We could talk about why this is happening, and I will talk a bit about it. But the fact is, countries are poor until they get rich. India and Bangladesh have been doing things that have made them grow steadily richer; Pakistan, in general, has not.

I could write a post giving policy suggestions for Pakistan to get richer — perhaps some mix of industrial policy, trade and tax reforms, infrastructure and education, and so on. At this point I probably don’t know enough to make highly detailed policy recommendations; my ideas would be things like trade openness with export discipline, land reform, investment in education, building infrastructure, improving rule of law, streamlining regulation, and so on. Fairly boilerplate stuff.

But I think a more fundamental question — or at least, a preliminary one — is why Pakistan’s leaders would do any of this stuff. If you don’t actually do the stuff, policy recommendations are useless.

To some, the answer might seem obvious: Growth makes your people materially better off. It gives them food to fill their bellies, a roof over their heads, convenient transportation, sanitation and health care, leisure and entertainment, and so on. Surely Pakistan’s leaders care at least somewhat about the welfare of their people, no?

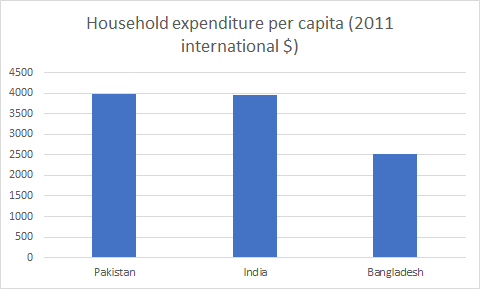

Well, they probably do. But so far they’ve been able to satisfy Pakistanis’ basic consumption needs through means other than economic development. The average Pakistani household consumes as much as the average Indian household, and more than the average Bangladeshi household.

But this comes at a cost; compared to India and Bangladesh, Pakistan invests far less of its GDP in building capital in order to grow its economy.

In other words, Pakistan is eating its proverbial seed corn instead of planting it in the ground. Bangladesh and India, in contrast, are planting their seed corn — foregoing current consumption in order to build productive capital and be richer tomorrow.

One of several things Pakistan does to sustain consumption is to chronically overvalue its exchange rate. If you peg your exchange rate higher than the market value, you can sustain higher imports for a while, but eventually you’re going to have a run on your currency and a “sudden stop”, requiring a bailout from the IMF or some other source. Pakistan has had a number of “sudden stops” over the years. And it has taken out quite a lot of loans from the IMF, including loans that were officially bailouts and loans that were not officially bailouts. Here’s a graph just through 2013:

Now, Pakistan is borrowing from its ally China as well.

In other words, Pakistan is behaving like a lot of natural resource exporters behave — but without the natural resources. Instead of a middle-income or high-income consumption society, it’s a low-income consumption society — keeping its people barely treading water, with lots of help from external largesse. That largesse is doubtless partly motivated by Pakistan’s strategic importance; it sits at the confluence of the War on Terror and Asian geopolitics, and it has nuclear weapons that no one wants to see fall into the wrong hands.

Why would Pakistan consume today instead of investing for the future? I’m not sure, but my guess is that it has to do with the country’s political system. The country alternates back and forth between civilian and military rule:

This chronic instability means that every Pakistani leader is inherently insecure in their position. If the people get mad at a civilian leader, they might let a military leader kick them out of office. And if they get mad at a military leader, they might kick them out and bring in a civilian. (Note: This applies even if the people with the power to kick out the leadership — the “selectorate” — is some elite subset of the populace, rather than the whole populace at large.)

And what tends to make people mad? Having to reduce their consumption, especially from a low base. If Pakistan’s leaders chose to do what Bangladesh does, and divert another 16% of its GDP to building capital instead of giving people the necessities of life, they might be kicked right out of power by a disgruntled populace. Bangladesh, with its greater political stability, is able to make the far-sighted choice instead.

Instability could discourage growth-oriented policy in another way, too. Growth creates new power centers — newly rich businesspeople who are able to spend money influencing politics, as well as newly affluent middle classes who have different political wants and needs. Any regime that chooses growth will have to deal with the shifting sands of power that result from that growth. And if your sands already shift a lot, the added instability might be too scary. Better to putter along for a while as a low-income consumption society, sustained by the IMF and China.

OK, but there’s one more reason to pursue economic growth: National power. Pakistan is right next to a neighbor with whom it has fought four wars (and arguably lost all four), and with whom it has an ongoing territorial dispute. India is more than 6 times as big as Pakistan, so only through greater per capita GDP could Pakistan seek to hold its own in a conflict. For many nations throughout history, this has provided a reason to seek rapid economic growth.

But unlike most of those nations, Pakistan has nuclear weapons. And that means that it doesn’t really have to get rich in order to guard against India; nukes guarantee its ultimate security. It might not be able to wrest Kashmir away from its neighbor, but it isn’t at risk of having further territory seized, or its capital occupied, etc.

This is interesting, because it suggests one way that nuclear armament might be detrimental to growth. Push-button superweapons greatly reduce the need for a state to be rich and effective — or even particularly stable — in order to maintain security from external threats. Perhaps we can see this with North Korea as well, or possibly even Russia.

In any case, my tentative, provisional answer to the question of “Why hasn’t Pakistan grown?” is that the right political incentives for growth-oriented policy are not in place yet. Perhaps a long period of stable civilian rule, or nationalistic envy of Bangladesh’s success, can change the calculus.

This post is a great example of why I love political economy but merely like economics.

Good read. Would be interesting to see your take on India’s economy at least in medium term. Complete the trifecta if you will.