Why the CTC is so important

It's more than a welfare program: It's the future of welfare.

(Even before you read this post, go sign this petition to save the Child Tax Credit!)

Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” bill is in peril. Senator Joe Manchin — the pivotal vote in the Senate — has declared that he’s a “no”, drawing a sharply worded statement from the White House. This comes after months of Manchin issuing various conditions and demanding various modifications. It’s not clear whether Manchin will eventually relent and allow something to pass, or whether he ever had any intention of voting for a major spending bill in the first place. This is obviously pretty bad, both for Biden’s agenda and — if you agree with me that much of Biden’s agenda is important to the country — for America.

But there is one silver lining, at least. Forced to reintroduce the bill, the Biden administration is refocusing it on what should have been the top priorities all along. BBB had become a massive kludge — a sort of grab-bag of priorities from a dizzying array of Democratic interest groups, reflecting the Dems’ extremely broad coalition. That breadth in turn pushed the bill’s authors to make many of the programs sunset early in order to make the whole thing cheaper, as well as adding various qualifiers and provisos to the programs that made them less efficient. Now, with Manchin’s stonewalling forcing Biden’s people to rewrite the bill, they appear to be doing what they ought to have done all along — focusing it on the key programs that advance the core of Biden’s economic vision.

Remember, I see Biden’s economic vision as having three basic prongs:

Investment

Cash benefits

Care jobs

Green energy subsidies go towards the investment piece, while the Child Tax Credit (CTC) provides both the cash benefits and increased demand for care jobs, while ACA subsidies also go toward #3.

Today, I want to talk about one of Biden’s core policies: the Child Tax Credit. This policy is still being massively underrated; people just don’t realize yet how potentially transformative it could be. Its impact is large, but the CTC’s importance goes beyond simple poverty reduction — it has the potential to redefine how we think of the welfare state and government’s role in our lives.

The direct impact of the CTC

We’ve had a Child Tax Credit for a long time, but the special version that Biden passed in his Covid relief bill earlier this year is different. First of all, it’s a lot bigger — the old version only went up to $167 per month per child, while the expanded version is up to $300 a month. Also, the expanded version is available to a lot more poor people; the old version insisted that people earn some income of their own in order to receive the benefit, while the new one was mostly unconditional. That meant that more money flowed to the poorest people.

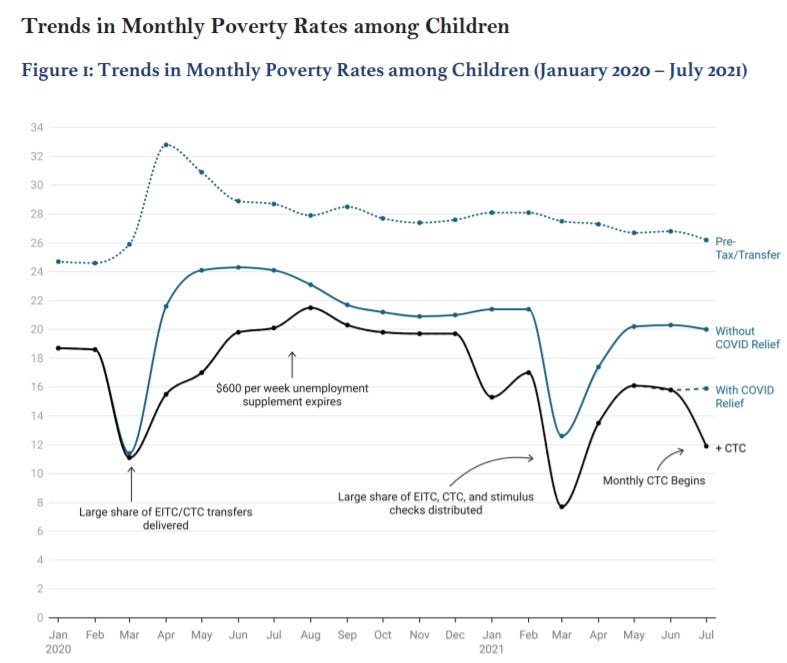

As you might expect, giving more money to poor people reduced poverty. Overall, Columbia University’s Center on Poverty and Social Policy estimates that Covid relief cut poverty by about a fifth, relative to where it was pre-pandemic and also relative to what it would be without the relief spending. For child poverty, the impact was even greater — a reduction of about 40% as of July, with the CTC accounting for about half of that.

This is more modest than the nearly 50% reduction that some had been predicting, but it’s still a very big deal, representing about 3 million kids lifted out of poverty. And the CPSP predicts that if the CTC were made permanent, the benefit would be even greater — up to a 40% reduction in child poverty going forward, if all eligible people were to use the program.

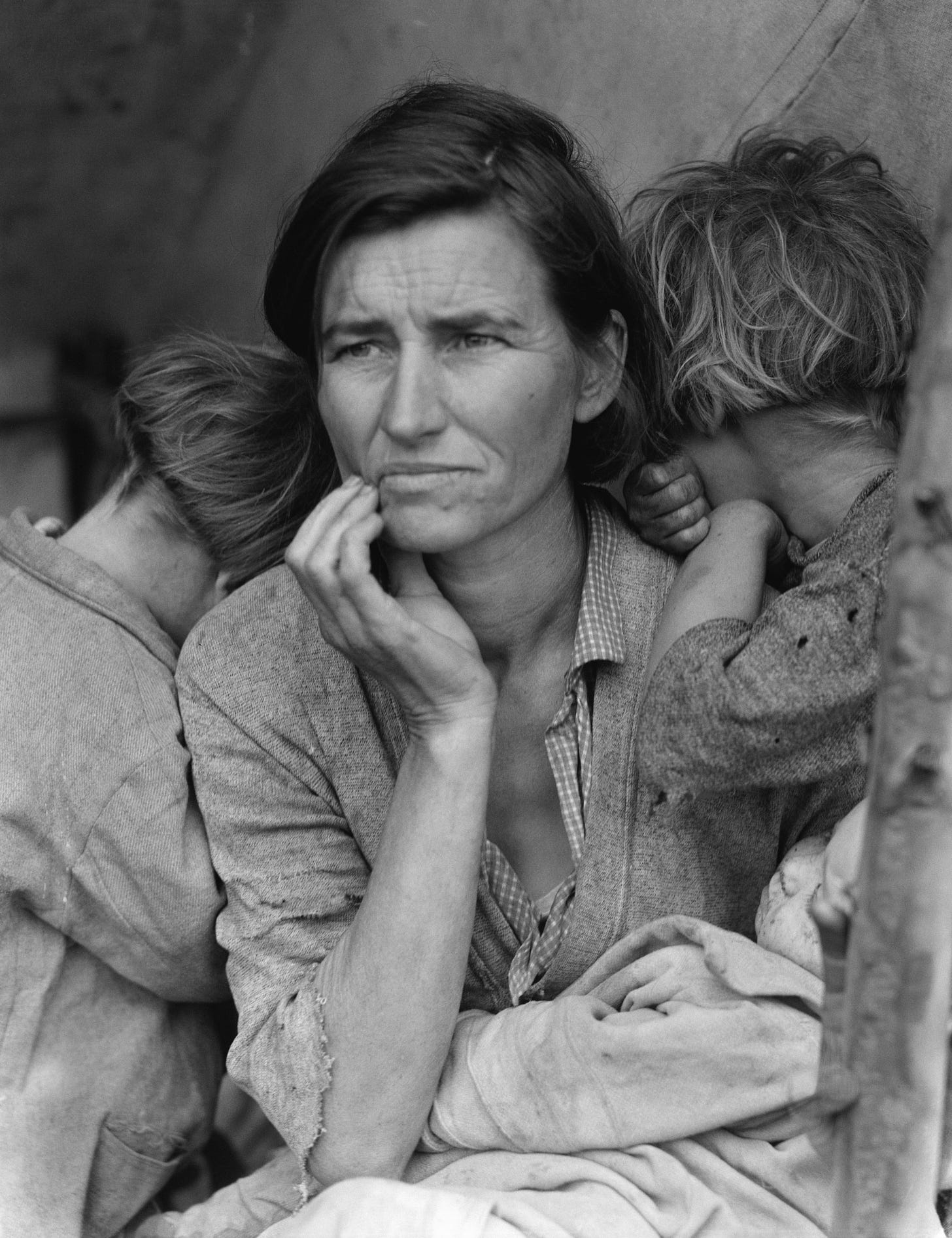

That would be a huge win for the country, and would help erase a great national shame. The U.S. has much higher child poverty rates than most rich nations — the harmonized measures used by the OECD put us at 21.2% (a fifth of all our kids!) living in poverty in 2018, compared to 12.4% in the UK, 11.8% in Canada, and just 8.3% in Ireland. That’s right, Ireland — a country once so poor that it once flooded America’s shores with destitute immigrants, and whose plight prompted Jonathan Swift to write a famous satire about selling babies for food — has a child poverty rate less than half America’s.

If you don’t think it’s a problem that a fifth of American children live in poverty, when only an eighth or fewer do in our peer nations, you should probably reevaluate your priorities! Correcting that problem should be plenty of reason to renew the CTC in perpetuity.

But in fact, the CTC’s importance goes far beyond its direct impact; it could transform how we think about what the government ought to do for the citizenry, and how the welfare state should operate.

A new vision of government

From the 1930s through the 1960s, the New Deal Democrats created a new vision for how government should protect its people from material deprivation and economic uncertainty. Essentially, the New Deal was a collection of A) programs targeted toward the various reasons people couldn’t be expected to earn a living, and B) programs that provided specific commodities that people needed. If you were too old, you could get Social Security and Medicare. If you were disabled, Social Security Disability. If you were thrown out of work through no fault of your own, you could get unemployment insurance, and so on. To the poor, the government also provided housing via public housing projects and later through Section 8 vouchers, food via food stamps, and medical care via Medicaid.

This collection of programs was essentially a huge collection of exceptions. It maintained the basic idea that some healthy, prime-age core of workers should still be expected to provide for themselves and their families with their own two hands. And for those who couldn’t, it made sure that the safety net explicitly provided for only the necessities of life, rather than awarding presumed laziness with luxury. In other words, the American welfare state’s complexity is an inevitable result of the country’s emphasis on work and personal responsibility. That same attitude carried through to the ways that the welfare state was reformed in the late 20th century — work requirements, time limits, income phase-ins for things like the EITC and the old version of the CTC, and so on.

Ronald Reagan came to power in 1980 promising a very different kind of economic relationship between the people and their government. Instead of giving you what it thought you deserved, he and his followers and successors argued, government should let you keep what you earned. Tax cuts were simple and easy — instead of writing endless reams of tax code and hiring legions of bureaucrats and lawyers to administer all the targeted programs, just eliminate all that waste with a stroke of a pen and let people keep the money they already had. Simple! And again, Reaganomics came from the idea of valuing work; it was the idea that the market had already valued the work people do, and that by letting them keep what they earned, the government was simply rewarding them for that work.

Note that each of these approaches had huge drawbacks. The New Deal programs were a giant kludge, with huge overhead and spotty usage. Reaganomics, on the other hand, was far simpler, but most of the benefits flowed to the rich.

But in recent years, there has been some talk of a third approach — one that combines the New Deal’s focus on the working class and poor with the simplicity and flexibility of Reaganomics. This approach is simply to give people cash.

Like Reaganomics, cash benefits let you choose how to spend your money, instead of some distant government bureaucrat or complex set of rules. But unlike Reaganomics, it doesn’t let the market decide who gets the checks — because cash benefits are paid for with taxes, they naturally redistribute income from the rich to the poor, even without phase-outs (though in practice there are always phase-outs somewhere up the income ladder).

Thus, the CTC is a best-of-both-worlds sort of solution — a program whose simplicity concedes the government’s inability to judge who does and who doesn’t deserve help and what kind of help they need, but which refuses to leave things to the market. It’s not all the way there yet — it focuses aid on people with kids, in order to take advantage of our natural sympathy toward families. But it’s a step toward the holy grain of universal, cash-based programs: A universal basic income.

The question, then, is whether cash-based programs represent a departure from the core organizing principle of the New Deal welfare state — an emphasis on work. Fortunately, evidence is accumulating that this isn’t such a departure after all.

A better kind of welfare, a different theory of poverty

The basic theory of poverty is that poor people are simply unlucky. Either they’re down on their luck due to life circumstances, or they were born without the natural gifts and family connections necessary to lift themselves up. This theory was the basis for the New Deal. During the conservative pushback that led to Reaganomics, a different theory of poverty arose — the idea that welfare itself trapped people in a cycle of dependency, discouraging work and causing people’s work ethic, skills, and self-reliance to degrade. This was behind the derogatory stereotypes of “welfare queens”, and it was also behind the push for work requirements in government programs.

In recent years, however, a third theory of poverty has arisen — the idea that the risks and transaction costs of life for a poor or working-class person living hand-to-mouth make it impossible for people to better themselves and boost themselves up to the middle class. A surprise medical bill can bankrupt a working-class family, but for a poor person, even a parking ticket or a busted water pipe can wreck their monthly budget. Add on the risk of becoming a victim of crime, the need to care for relatives who are also poor or suffer setbacks, and the precarious job situations (at-will employment, uneven working hours) that wage-earning Americans have to deal with, and you have a world that’s chock full of terrors. Now add on the hassle — the time spent getting one’s car out of the tow or bailing out a relative arrested for drug possession, the difficulty of finding a new job, the desperate search for a new place to live after an eviction. And since people near the bottom of the income distribution also tend to have few assets, there’s very little cushion there to fall back on.

In other words, poor and working-class people are getting nickel-and-dimed to death. The economist Sendhil Mullainathan has argued persuasively that this constant barrage of risk and hassle traps people in a daily struggle for survival, and thus makes them unable to do things that bring long-term gains — things like getting an education, improving their health, forging better personal relationships, finding a better job, saving some money, or moving to a better place.

The obvious solution is simply cash. Cash creates a cushion that at least partially buffers people against any and all of life’s risks and costs. This seems to be validated by an (admittedly small) pilot program in Stockton, CA, in which 125 families in lower-income neighborhoods received $500 a month. Rather than quitting work to live off of their free checks, the recipients actually tended to move into full-time work, and reported that they were thinking more about the future.

In fact, this is pretty similar to the modal experience with cash-based welfare programs. Economist Ioana Marinescu has a 2018 literature survey collecting studies of a bunch of cash-based programs, and she finds:

Many studies find no statistically significant effect of an unconditional cash transfer on the probability of working. In the studies that do find an effect on labor supply, the effect is small: a 10% income increase induced by an unconditional cash transfer decreases labor supply by about 1%. The evidence shows that an unconditional cash transfer can improve health and educational outcomes, and decrease criminality and drug & alcohol use, especially among the most disadvantaged youths.

Probably the most famous paper in this literature is a 2018 study that Marinescu did with Damon Jones, finding that cash distributions from the Alaska Permanent Fund (which distributes natural resource extraction profits to the people of Alaska) didn’t discourage people from working.

And in fact, we don’t have to look for loose analogues like that in order to predict the effect of Biden’s expanded Child Tax Credit — we can just look at Canada, which has a very similar (but even more generous) policy called the Canada Child Benefit. A very recent paper by Michael Baker, Derek Messacar and Mark Stabile examined the impact of this program (along with a separate program that provides money for child care), and found:

Our analysis indicates that both reforms reduced child poverty, although the Canada Child Benefit had the greater effect. We find no evidence of a labor supply response to either of the program reforms on either the extensive or intensive margins.

In other words, even if there are some people who use a government check as a reason to take an extended vacation, they’re balanced out by the people for whom a government check is a cushion that lets them avoid the daily struggle and get back to work. For many poor and working class people, a handout is a hand up, plain and simple.

So there’s a real chance for Biden’s CTC to move us toward an updated vision of government, poverty, and the welfare state — something that reflects all we’ve learned since the days of Franklin D. Roosevelt. In the short run this may depend on the whims of Joe Manchin, but going forward, even Republicans might get on board with the idea. After all, it was Republicans who first sent out the pandemic “stimmy” checks in early 2020. And Mitt Romney has come out with his own child tax credit proposal that is superior in some ways to what Biden is putting forward.

That’s why I’m glad that as Biden narrows the focus of his legislative agenda, he’s keeping the CTC at the center of it. There are plenty of good programs out there, but few with as much transformative potential. The move toward unconditional cash benefits has been building for a while, and the pandemic gave it a boost. Whether or not it gets through this time, we need to keep pushing.

(Anyway, if you agree with me, go sign that petition!)

Noah,

I just recently found your SubStack and it is great! I had two thoughts from reading this piece.

(1) Comparing the US to Ireland is feasible but comparing it to the EU is perhaps a more correct way to assess American poverty. Whether we like it or not, the civic structure of America is very federal, with semi/quasi sovereign states. America is like a more united EU-a continent spanning superstate with very different regions and sub-interests. Ireland just does not compare. It is structured differently. Perhaps we should ask why Ireland has better poverty stats relative to the state of Hawaii or Mississippi.

(2) Also, when we look at many of the Top 1% they often make great wealth through investments. We need to find a way as a nation to leverage investing to benefit those in poverty. That is where huge fortunes are made.

Great post as always. One small correction: "But it’s a step toward the holy grain of universal, cash-based programs" --> "holy grail", or maybe you're trying to sell farmers on the idea ;)