Why renewable subsidies are better than carbon taxes

Democrats got this one right, and economists were left in the dust.

The Inflation Reduction Act is first and foremost about creating abundance — about lowering the cost of living for the average American. It also just so happens to be the most significant piece of climate legislation in U.S. history. Climate wonks are overjoyed, and rightly so.

But the IRA didn’t approach climate change the way most climate economists wanted it to. For decades, climate economists have focused rather obsessively on the idea of carbon taxes. While Democratic politicians were talking about investment and green jobs and technology, climate economists were maintaining their laser-like focus on measuring the “social cost of carbon” so we could design the perfectly-sized tax. Bob Kopp of Rutgers has a good thread of soul-searching about why climate economists ended up making themselves so irrelevant to climate policy, and what could be done to correct course:

Except for a tax on methane emissions, the IRA employs subsidies rather than taxes. Instead of charging companies for emitting greenhouse gases, subsidies pay companies to switch to specific renewable technologies like solar power and electric vehicles. Economists tend to think carbon taxes are superior to subsidies, because taxes allow companies to reduce emissions by whatever is the most efficient method (renewables, energy efficiency, simply cutting production, etc.), while subsidies focus only on specific alternatives for specific pieces of the emissions puzzle.

So why have climate policymakers so resolutely ignored carbon taxes and focused on subsidies instead? Part of the reason is politics — taxes make people feel poorer, even if you pair them with cash benefits, which is why carbon tax initiatives fail at the ballot box even the greenest of states. But in fact there’s a deeper economic reason why they IRA’s subsidy-centric approach is better than what climate economists would have given us. Renewable technology subsidies are simply a better climate policy than carbon taxes, and the climate economists didn’t realize this because they were asking the wrong question.

The real climate problem

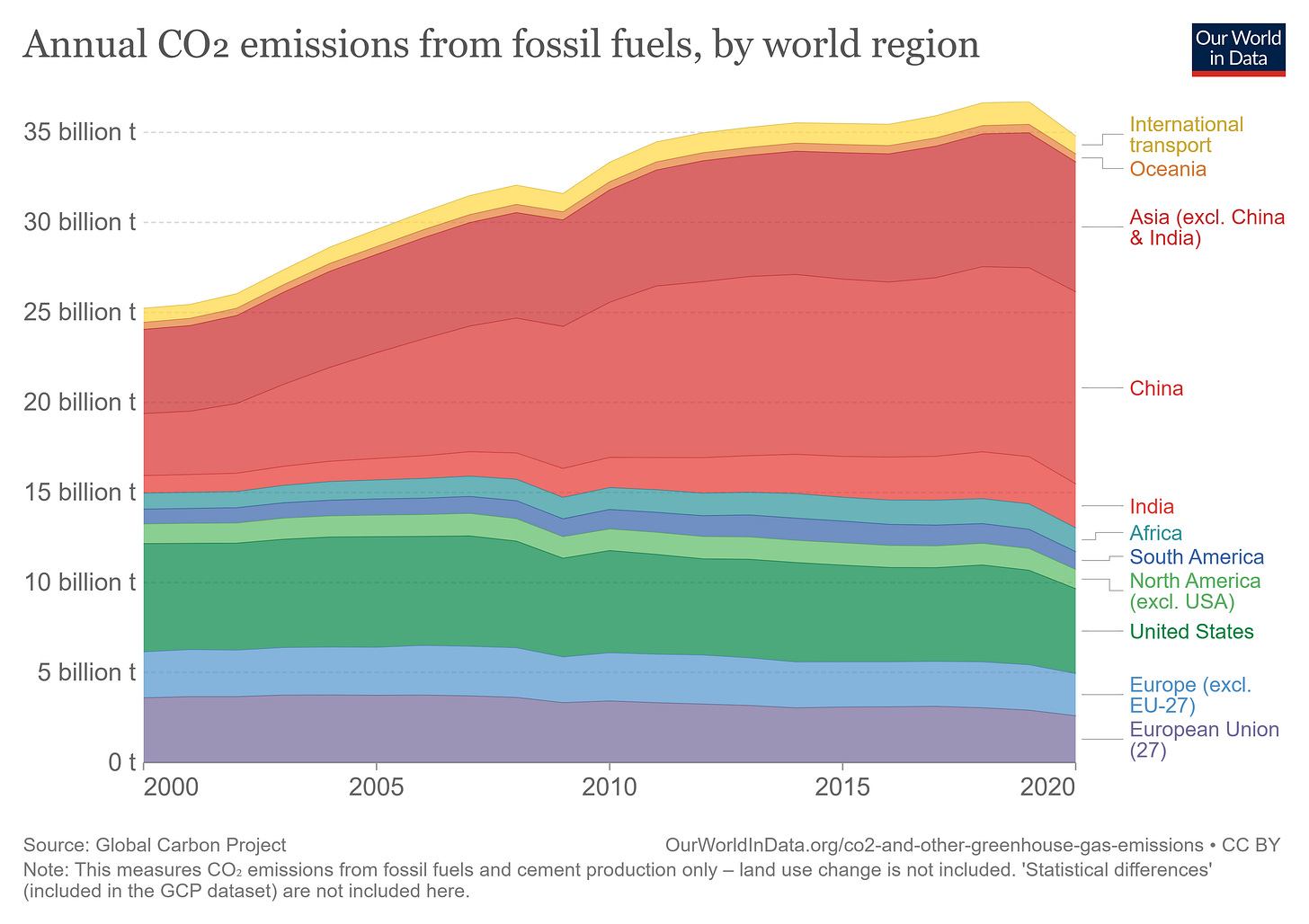

The fundamental fact about global warming is that it’s global. Greenhouse gases contribute the same amount to climate change no matter where they’re emitted. And the U.S. represents only around 14% of global emissions, a number that is falling every year:

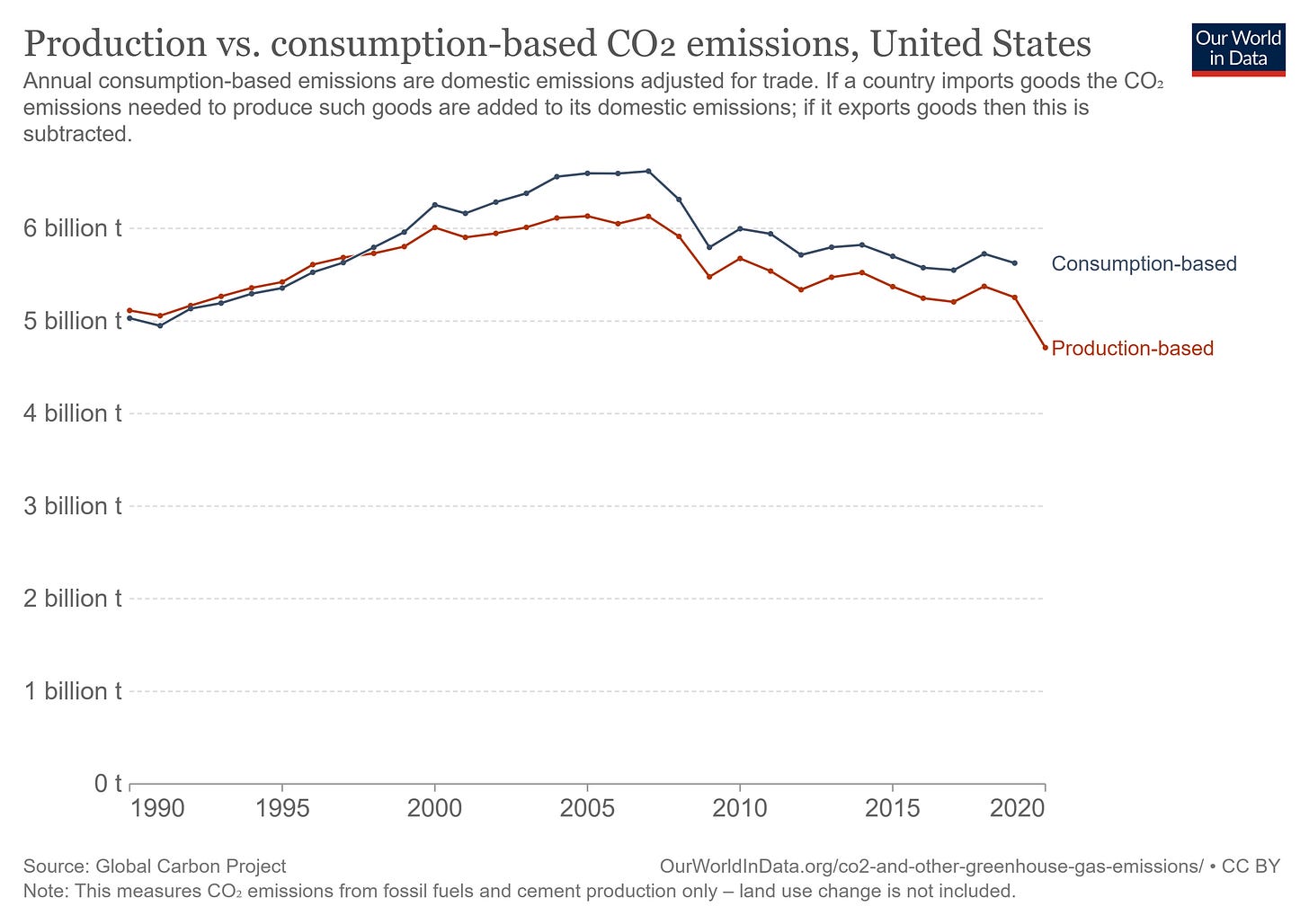

And no, this is not because the U.S. outsources a bunch of our emissions to manufacturing-intensive countries like China. When you look at the emissions produced by U.S. consumption, it’s just not that different:

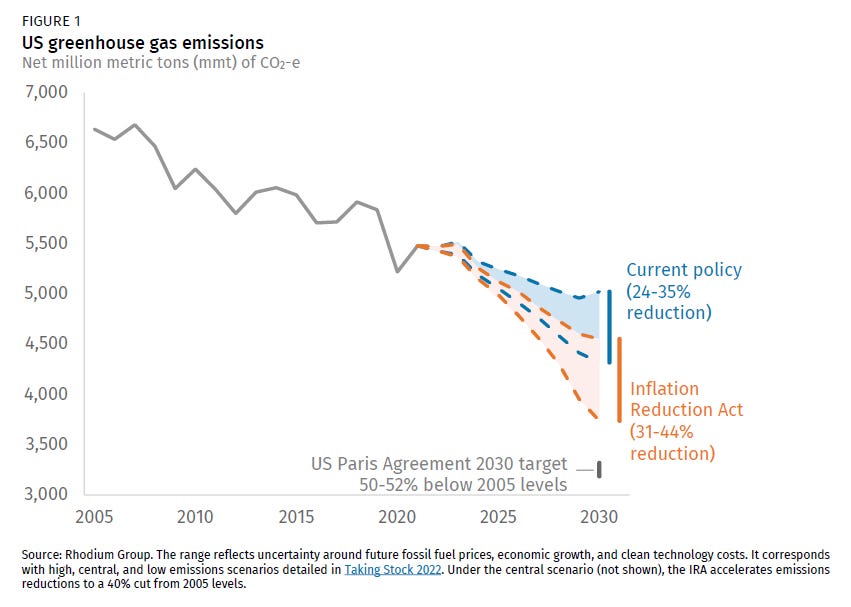

So even if a U.S. carbon tax were applied to imports as well, it would have only a very limited ability to curb climate change. Even if you zeroed out U.S. emissions completely, it would represent only a moderate reduction in the global total. But of course realistic policies, including our Paris Agreement commitments, won’t come close to zeroing us out anytime soon. A recent analysis by the Rhodium group shows just how much of a reduction we can expect in the next decade:

We’re already reducing emissions somewhat, due to cost reductions in renewable technologies. If we met our Paris commitments, by this analysis, it would result in an additional decrease of between 17 and 26 percentage points over what we can expect to achieve otherwise. That’s quite substantial, but it still represents a decrease in global emissions of only 2.4% to 3.6%.

But in fact, that’s just the direct effect. What would China and the rest of the world do in response to the U.S. meeting our Paris commitments? The rest of the world emits 86% of carbon emissions and rising, so this is a really crucial question.

There are basically two schools of thought here. The first is that the U.S. exercises an almost magical degree of “moral leadership” in the world, such that if America decarbonizes, China and other countries will follow suit out of shame or out of desire to retain their international standing. This idea strikes me as extraordinarily unlikely. The U.S. can’t even get China (or India) to join sanctions against Russia. China is gearing up for military conflict with the U.S., with its officials constantly tweeting out stuff like this:

This is not a country that thinks America is some sort of shining moral beacon it needs to emulate. And developing countries like India are concerned first and foremost with alleviating poverty. Europe, meanwhile, has been making its own decarbonization efforts; at best the U.S. will be racing to catch up in that regard.

A more likely scenario is that China and developing countries take advantage of U.S. carbon taxes in order to buy cheap fossil fuels. If carbon taxes reduce U.S. demand for oil and coal, that will decrease the prices of these things on the international markets. China and others can then buy them cheaply.

In fact, you can see something very much like this effect at work in the markets right now — China’s recession is lowering demand for oil, which is causing oil prices to fall. All else equal, that price drop will raise oil consumption in the U.S. and all over the world, which will cancel out some of the climate impact of China’s recession. Similarly, if the U.S. imposed a carbon tax to reduce our own demand for oil (and coal), the international price drop would cancel out some fraction of the positive effect.

There’s just really not a lot you can do about this. Global warming is a global externality, yet policy is made at the national level. Climate economists, obsessed with salvaging the carbon tax idea, have come up with byzantine schemes for clubs of countries to use coordinated tariffs or other economic sanctions to punish countries that didn’t implement their own carbon taxes. But this is basically just fantasy-land.

If you want to use one nation’s policy to push the whole world to decarbonize, you’re going to have to do better than single-country carbon limitations. Note that this also applies to regulations that ban coal, or fracking, etc.

Fortunately, we do have a policy that will not only reduce America’s emissions but also influence the world at large to give up fossil fuels. That policy is subsidies for specific renewable technologies — the exact approach used by the Inflation Reduction Act.

The thing economists neglect: learning curves

In terms of cutting emissions directly, the Inflation Reduction Act is no more of a global game-changer than a U.S. carbon tax would be. The bill is a great step and a landmark victory, but the people who say that “the planet has now been saved” are pulling your leg a little bit. In fact, the Rhodium Group analysis above predicts that the bill will decrease U.S. emissions by an amount that corresponds to only about 1-1.3% of global total emissions. So why do I keep saying that the IRA’s subsidies are better than carbon taxes?

There are two reasons. The first, which economists know about but often just ignore, is the international price effect that I talked about above. Carbon taxes make fossil fuels cheaper. Renewable subsidies do not make fossil fuels cheaper. Thus, the effect of subsidies is not partially canceled out by international price effects, the way the effect of carbon taxes is. Score one for subsidies. (Note: As someone in the comments pointed out, renewable subsidies actually do decrease global fossil fuel prices a bit as well, though less than carbon taxes.)

But in fact there’s a far more important advantage of subsidies. They’re much better than carbon taxes at taking advantage of learning curves.

Learning curves for renewable technology are something that every climate wonk and energy wonk seems to know about, and no climate economist seems to know about. Ramez Naam, my favorite energy wonk, has been yelling about learning curves for over a decade now. The basic idea is that the more you build of a technology — solar panels, or lithium-ion batteries, etc. — the cheaper it gets. There are several reasons for this — economies of scale, learning-by-doing, incentives for follow-on innovation, etc. It’s now widely believed that learning curves are behind the amazing cost drops we’ve seen in both solar and batteries over the past few decades. Here’s a good Ramez thread about solar learning curves, where you can actually see the curves graphed out:

Now, as any economist knows, it’s important to know whether these learning curves are causal. Of course as stuff gets cheaper there’s an incentive to install more of it, and learning curves aren’t the only reason stuff can get cheaper over time. So we have to make sure that installation is actually driving price declines before we decide that learning curves are magic. There are some papers out there about learning effects in general, but these probably don’t tell us much about the specific cases of solar and batteries.

Fortunately, there is a lot we can observe directly about the sources of costs in the solar industry, just by looking at detailed data from within the industry. For example, if utilities find that it’s cheaper to build bigger solar plants, then we pretty much know that funding the building of larger plants will drive costs down. And if we observe that plants become more efficient at installing panels over time without any change in what they’re installing, we know that learning-by-doing is at work. We can then roughly decompose cost declines into all the factors we can observe.

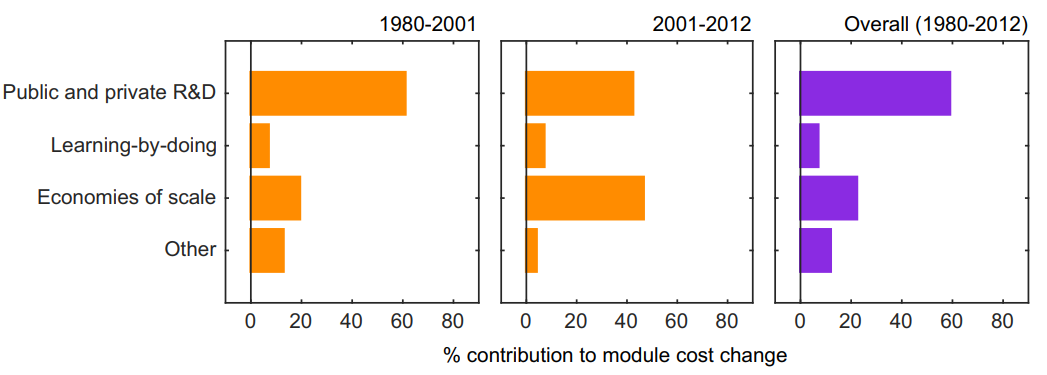

My favorite paper that does this is Kavlak, McNerney, & Trancik (2018). Looking at a bunch of industry data on solar costs, they find that in the early days of solar, R&D was responsible for most of the cost decline. But since the turn of the century, economies of scale and learning-by-doing have been responsible for a little more than half of the solar cost decline:

So learning curves may not be 100% causal, but there is lots of causality there. Batteries might be different of course, but it seems unlikely, given that Li-ion and similar technologies are now fairly mature. (And of course, remember that R&D can also be part of learning curves. When demand for a product increases, there’s more incentive to pour research money into figuring out how to make more of that product.)

In other words, we can be fairly confident that for a lot of renewable technologies, simply building more of the stuff will push down the price.

This is where subsidies shine. Carbon taxes can incentivize a switch to greener technologies, but they can also incentivize cutting back on production or improving energy efficiency. Subsidies for renewables, on the other hand, simply incentivize building more, more, more. And because of learning curves, that drives down the price of renewables.

And when renewables get cheaper, it gives China and India and all the other countries out there an incentive to decarbonize that has nothing to do with climate change. These countries will naturally tend to balk at the idea of tightening their belts and cutting back for the good of the planet — China because they want to be tough and strong for geopolitical dominance, India and other developing nations because they want to escape desperate poverty. But if renewables are just cheaper than fossil fuels, those other countries will switch simply because it makes hard-nosed economic sense.

And in fact, there are signs this is happening. China is building so much renewable energy that they’re worried about losing farmland to solar plants!

And solar is so much cheaper than coal in India now that the country is rapidly shifting from the latter to the former. Other developing countries in Asia and Africa and Latin America will doubtless do the same, because renewables are now simply cheap as heck.

Carbon taxes never could have done anything like this. This was a function of the magic of technology, and of learning curves. Countries like Germany and China that subsidized solar in the 2000s and 2010s, even before it made economic sense, helped push those costs down and accelerate this trend.

And the subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act will do the same. The incentives for the deployment of solar power, electric vehicles, hydrogen, heat pumps, electric home appliances, and other renewable technologies on a mass scale in the world’s largest (or second-largest) economy will continue driving the prices of these technologies down, and give all the countries of the world an incentive to adopt all of these things at an accelerated pace — which will in turn drive down prices even more. It’s a virtuous cycle — a key part of the Green Vortex that’s our best hope for beating climate change.

Economists simply missed this. Not because the discipline of econ is blind to the idea of learning curves — in fact, the ideas of economies of scale and learning-by-doing come from econ. But for some reason, economists only considered climate policy in terms of a single externality — the negative externality of greenhouse emissions. In fact, there was another externality at work — the positive externality of technological progress — that we could harness to fight the negative one.

And thanks to climate wonks and Democratic politicians, we are going to harness it. We’re going to make “cheap energy” and “green energy” synonymous. And we’re going to accelerate the virtuous cycle of decarbonization, not just in America but all around the globe.

I wonder if industrial policy skepticism explains the fixation on carbon taxes.

If you associate subsidies with wasted money spent trying to "pick winners," you're going to prefer an agnostic approach like a carbon tax.

It seems like industrial policy is back in fashion these days. Hamiltonian approaches get much more respect than a generation ago. Maybe it was the ideas in fashion in the 1990s, as much as anything else, that accounted for climate economists fixing on a carbon tax as the One True Policy.

Great post. Three points confused me, though.

First: you say "the effect of subsidies is not partially canceled out by international price effects, the way the effect of carbon taxes is."

But why should foreigners care why we're using less oil? Oil will be cheaper for them no matter why we shift away, whether to avoid taxes or exploit subsidies.

Eg, if the USA magically converted all fuel and power to renewables tomorrow, wouldn't the plunge in oil prices from American disuse lead to more foreign oil use and somewhat higher foreign emissions, whether the magical conversion at home was achieved by subsidies or taxes?

That is:

1) carbon taxes make us use less oil, because for us oil is pricier, but

2) renewable subsidies also make us use less oil, because for us renewables are cheaper, so

3) both carbon taxes and renewable subsidies reduce our oil use, so

4) both carbon taxes and renewable subsidies should lower oil prices elsewhere, so

5) both carbon taxes and renewable subsidies suffer partial cancellation of their intended "changed relative domestic prices reduces emissions," because foreigners use more oil.

Is this wrong? If it's right, how isn't this the same problem for subsidies as taxes?

The answer might be "okay, technically subsidies do also induce a foreign rise in oil use following domestic disuse, but it's overwhelmed by the learning effect," but you don't say it that way in your post.

The second thing that confused me: you say subsidies encourage learning, but taxes don't.

But in theory, higher oil prices should also encourage more investment in non-oil power sources, and more R&D in energy efficiency.

What is it about renewable subsidies that generates an unusually high learning effect?

The answer might be "energy efficiency doesn't exhibit the same kind of massive scaling we're seeing in solar, batteries, etc." That's plausible, since solar etc represent new industries with lots of concentrated development, whereas efficiency probably involves a bunch of different steps in a bunch of different places. So "new efficiency knowhow" could easily be much harder to copy on and scale up than "new solar knowhow."

Alternatively, the answer could be that a fair chunk of carbon taxes' effect would simply be in reduced consumption, which doesn't generate learning.

Third, you suggest economists were blindsided by the scale of these learning effects. Is that because the economists were naive, and this always happens with a new power industry? Did this happen with coal and oil and nuclear?

Or are solar and wind and batteries unusually good at having scaling effects, in a way that previous energy technologies weren't?

It's true that solar and wind and batteries are all made of high-tech mass-manufactured objects, and solar in particular exploits circuitry technology nearly as much as computer chips do.

But should it have been obvious that windmills would have more learning payoffs than oil wells, for example? Or were there historical large learning effects to oil adoption that the climate economists just forgot to generalize from? Or is today's "green power learning" a fortunate surprise that only a real expert would have predicted early?