Why price controls are a bad tool for fighting inflation

They have their uses, but this isn't one of them.

Economist Isabella Weber caused a stir when she wrote an op-ed in the Guardian calling for price controls in order to fight inflation. She wrote:

[A] critical factor that is driving up prices remains largely overlooked: an explosion in profits…[L]arge corporations with market power have used supply problems as an opportunity to increase prices and scoop windfall profits. The Federal Reserve has taken a hawkish turn this month. But cutting monetary stimulus will not fix supply chains. What we need instead is a serious conversation about strategic price controls…

Price controls would buy time to deal with bottlenecks that will continue as long as the pandemic prevails. Strategic price controls could also contribute to the monetary stability needed to mobilize public investments towards economic resilience, climate change mitigation and carbon-neutrality. The cost of waiting for inflation to go away is high.

Paul Krugman wrote a brief thread explaining why he didn’t like this idea:

Stephanie Kelton (the most prominent MMT advocate) then wrote a rebuttal to Krugman that she claimed was posted on behalf of the economist James Galbraith. This should remove any doubt that price controls are one of MMT’s front-line policies against inflation. But the MMT people are not alone — J.W. Mason and Lauren Melodia of the Roosevelt Institute list price controls as one of several policies for fighting inflation:

When prices are rising rapidly for basic necessities that people cannot delay consuming—like housing, food, and medical care—it may be necessary to adopt rules that limit how fast prices can rise or set a cap on prices…In periods of crisis and national emergencies, the government has used its power to implement economy-wide price regulations, setting a ceiling on price increases for a wide range of goods and services. Economy-wide price regulations are unlikely to be called for in the contemporary United States, but there are many cases where the government can take action to limit price increases for particular goods and services.

I’m on Krugman’s side here — I don’t think price controls are always bad (they’re useful in war, or in certain markets that are very distorted), but I think they’re very bad as a tool for fighting inflation. But I don’t think Krugman quite managed to capture why I think this idea is so bad. The real dangers from price-controls-as-inflation-policy, as I see it, are A) the signal it sends about monetary policy, B) the possibility that inflation will be exacerbated by shortages, and C) the possibility that inflation will be exacerbated by alternative currencies.

Price controls: Simple theory

If there’s one thing you should know about macroeconomics, it’s this: Convincing evidence is really really hard to come by, so people end up relying a lot on theory and making a lot of assumptions. Price controls are no different. So we can’t just point at evidence for whether price controls are good or bad; we have to think about how we believe the economy works.

Anyway.

The basic theory of competitive supply and demand says that price ceilings cause shortages. Here’s the graph showing the theoretical gap between how much people want and how much they get when government caps the price of something:

The basic logic here isn’t complicated. Government declares that milk shall be super-cheap. People say “Oooh, milk is super cheap!” and rush out to buy milk. The shelves empty out and there’s no more milk. The people who were late to the store can’t find any milk, and they get mad. The end.

But this perfectly competitive model is often a bad description of reality. Sometimes, as we’ve seen with minimum wage, price controls don’t distort markets by a noticeable amount. In that case, the model we want to think about is more like a monopoly model. When there’s monopoly power in the economy, a price ceiling can actually move the price toward what it ought to be, and relieve shortages instead of exacerbating them. Here’s what that graph looks like:

When Weber cites corporate profits as the cause of inflation, or when White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki talk about inflation being due to the “greed” of corporations, this sort of monopoly power is probably what they have in mind. (Update: Here is a good post by Joey Politano throwing some cold water on this explanation.) Monopolies make goods more expensive and limit the amount people can consume; a modest price ceiling can make goods less expensive while also making them more abundant. (The price ceiling prevents companies from jacking up prices as much as they’d like, so the next best thing they can do is to increase volume.) So price controls aren’t always bad!

But does this make any sense when talking about inflation? Monopoly models like the one in the picture above are static, long-term equilibrium models; they don’t say much about the rate of change. It’s probably not plausible that monopoly power would change significantly in the course of one year due to supply bottlenecks. In other words, as Matt Bruenig points out, if powerful companies could have jacked up prices before now they would have done so; if their ability to jack up prices has increased, it’s probably not because they’ve suddenly become much more powerful.

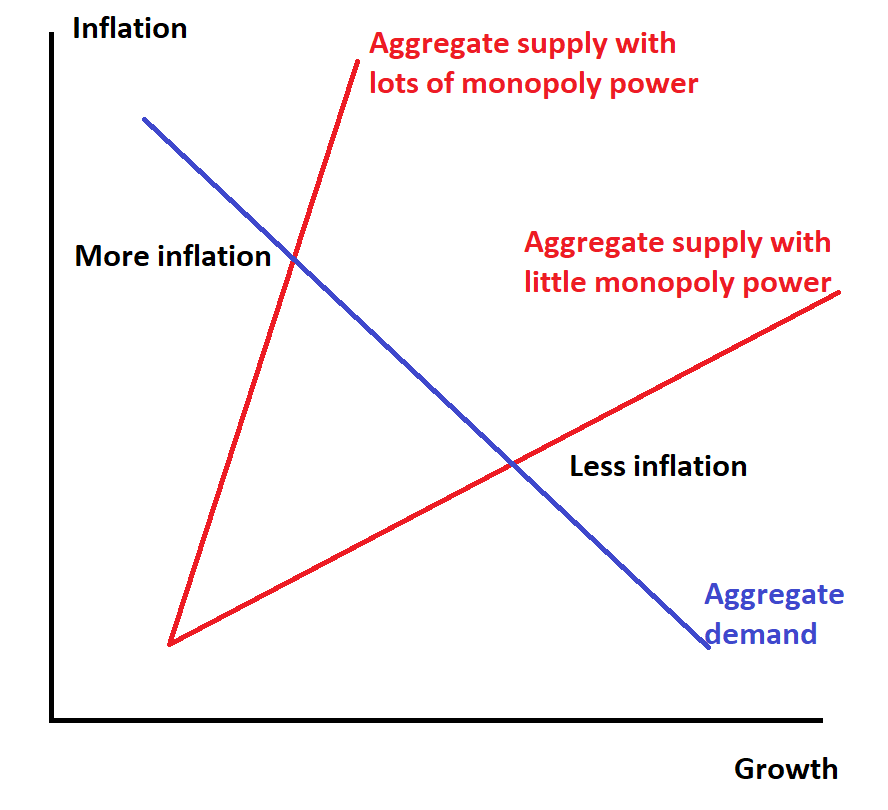

OK, let’s think in terms of a simple macroeconomic model — aggregate demand and aggregate supply. Here, growth and inflation — i.e., rates of change — are on the axes, rather than static amounts. And it’s conceivable that an economy with lots of monopoly power in various markets might have steeper supply curves in those markets, which in turn might make aggregate supply steeper, which would make inflation tend to be higher. That would look like this:

But if this is how the economy works, would price controls in various markets reduce inflation at a time like now? Probably not, no. Go back and notice that in the monopoly model, the price ceiling doesn’t actually change the supply curve. So if the aggregate supply curve just comes from some sort of summation of companies’ individual supply curves, price controls aren’t going to change the aggregate supply curve either.

Because remember, even if there are monopolies in each market, that doesn’t mean the macroeconomy overall acts like a monopolized market. There’s no one company that has a monopoly over aggregate production. So price controls, macroeconomically, are likely to reduce inflation only at the cost of causing a recession:

That would be a bad idea; sure, we’d beat inflation, but we’d throw a ton of people out of work. If that’s what we want to do, we might as well use monetary policy.

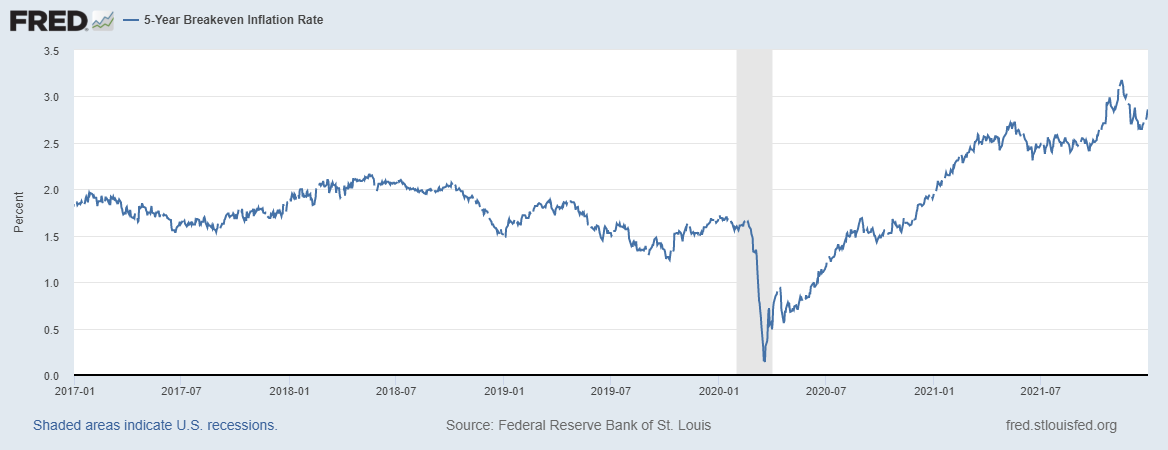

But we shouldn’t do that. It’s not worth it, just as it isn’t worth it to pull a Paul Volcker right now and crush employment in the name of bringing inflation back down to 2%. As long as inflation doesn’t spiral upward, it’s only doing minor harm. And the Fed seems to have kept a lid on inflation expectations:

So maybe the Biden administration will find it politically advantageous to control the prices of some highly symbolic goods like gasoline, or spout a bunch of populist condemnation of the evil greedy corporations. But simple theory suggests that that enacting economy-wide price controls just to bring inflation back down to 2% is not worth the damage it’ll cause.

Price controls: More complex theory, and why they’re scary

But simple theories like AD-AS aren’t always sufficient for determining policy. Real macroeconomies have a lot more going on — there are expectations and beliefs, coordination problems, information problems, and all sorts of complex stuff. Price controls are something we don’t see every day (though it’s helpful to look at history, as we’ll talk about in a moment), so it’s possible they’ll lead to some weird, unusual macroeconomic effects.

One possibility is that if price controls do cause empty shelves — as they will if they’re strong enough to overcome the amount of monopoly power in the economy — that this will cause people to engage in hoarding behavior. Martin Weitzman explained how this can happen in a 1991 paper called “Price Distortion and Shortage Deformation, or What Happened to the Soap?” He used this concept to explain chronic shortages in the Soviet Union. This effect goes well beyond the standard “Econ 101” explanation of why price controls cause shortages.

And when we’re talking about inflation as a price control measure, hoarding could be especially bad. It would boost demand (because everyone is trying to hoard), which will lead to even more inflation, causing the government to respond with even more price controls, etc. That would be a very unpleasant spiral, even beyond the hardships and unfairness created by hoarding. This possibility of a price-control-inflation spiral has occurred to economists, but it’s very hard to measure. Anecdotally people talk about cases where something like this seems to have happened.

And that’s not the only theoretical reason why price controls could exacerbate inflation. Many economists theorize that inflation is, at least sometimes, determined by people’s beliefs about monetary policy. If people think the government (especially the central bank) doesn’t care that much about fighting inflation, then they’ll raise prices now in anticipation of future cost increases, causing fear of inflation to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is one leading explanation for the high inflation of the 1970s — the oil shocks caused some prices to rise and the Fed didn’t respond, which convinced people that the Fed didn’t care that much about inflation, which caused inflation to spiral upward much more than the oil shocks should have caused just by themselves. It’s also part of the story many economists tell about how hyperinflation — which is truly devastating to a country’s economy — gets started.

So if price controls became the government’s primary tool for inflation-fighting — as Kelton suggests — it could send a very dangerous signal. It could convince the public that the government isn’t willing to use monetary policy to do the job. In a post last May entitled “When to worry about inflation”, I wrote:

I think there’s another important warning sign to keep an eye out for. If policymakers start seriously talking about price controls as a way to manage inflation, it’s a very bad sign…[I]f it becomes clear that the Fed is no longer the first line of defense against inflation, then inflation is probably on the way.

So far, we’re not seeing anything like this. The Biden administration has suggested price controls on prescription drugs, and they are understandably very fixated on supply-based explanations for inflation rather than demand-based ones. But this doesn’t yet appear to translate into the idea of price controls as an inflation-fighting approach. There’s no sign that Biden and his people are listening to Stephanie Kelton, James Galbraith, or the MMT people, or even to the much more moderate Roosevelt Institute.

And more importantly, the Fed itself doesn’t seem to be shifting even slightly toward the idea of price controls. They’re definitely using strong forward guidance as well as actual concrete policy measures — QE tapering and rate hikes — to reassure the market that they still care about inflation. And with inflation expectations seemingly under control and growth still strong, they look to have succeeded.

But it’s still useful to remember the possibility that shifting toward a reliance on price controls as the first line of defense against inflation could bring about the very inflation it’s designed to prevent.

Price controls: History and evidence

So that’s the theory. What does evidence say? Remember that in macroeconomics it’s very hard to get the kind of clean, convincing evidence that we have for policies like the minimum wage; macroeconomic stuff affects everything and is affected by everything, so it’s incredibly hard to disentangle cause and effect. But it’s still important to look at evidence, and the lessons of history, for crumbs of insight.

Unfortunately, there is a paucity of careful historical studies of price controls as inflation-fighting policy. This is probably due to the unfortunate fact that macroeconomists thought inflation had been conquered, and thus haven’t been very interested in studying it in recent years. But there are a few things we can look at.

Justin Damien Guenette of the World Bank wrote a paper in 2020 in which he looked at the history of a variety of price control regimes in developing countries, and concluded that the effect on growth and employment generally seemed to be negative.

Economists Diego Aparicio and Alberto Cavallo recently took a look at some targeted price controls in Argentina (Argentina traditionally has a lot of inflation, so it’s a good place to look for evidence; this is also probably why it produces so many great macroeconomists). These targeted controls are similar to what the Roosevelt Institute people might recommend. The economists found that the controls accomplished very little but also did little harm:

We first show that price controls have only a small and temporary effect on inflation that reverses itself as soon as the controls are lifted. Second, contrary to common beliefs, we find that controlled goods are consistently available for sale. Third, firms compensate for price controls by introducing new product varieties at higher prices, thereby increasing price dispersion within narrow categories. Overall, our results show that targeted price controls are just as ineffective as more traditional forms of price controls in reducing aggregate inflation.

So, that’s somewhat reassuring; at least targeted, Roosevelt Institute type controls wouldn’t be disastrous. (Though it’s worth noting that Argentina already has pretty wacky macro policy, and thus it might not have much public confidence left to lose; similar moves by the U.S. government might have a more deleterious effect.)

A more well-known example is the Nixon price controls that began in 1971 and were mostly ended by Gerald Ford in 1974. Economists’ standard story of these price controls, as laid out in a paper by Alan Blinder and William Newton, is that they temporarily suppressed inflation a little bit, but that this only caused a bigger rebound later. You can kind of see that in the data:

Note that prices were already accelerating in 1973. The more prices go up, the more a given price control will bind (i.e. the harder it’ll hit producers), and the worse the shortages it’ll tend to cause. So inflation from the oil shock can be seen as having broken the back of the Nixon price controls, causing even more inflation, much as a wave of capital flight from a country can break its currency peg and cause even more capital flight as a result.

A more successful example is the wartime price controls during WW2. These didn’t prove inflationary. Private consumption did fall, but not because of aggregate shortages or an economic slowdown; instead, the government was simply redirecting production toward the military on a mass scale. Also, there’s little reason to think that monetary policy expectations or hoarding behavior would have been much in effect during the war. So this example probably isn’t that applicable to the current situation.

Then there are some examples of when price controls seem to have been a key part of a truly disastrous macroeconomic program. One of these is Venezuela. Here’s a well-sourced blog post with some of the relevant history:

A price ceiling was fixed in 2003 on all staple food items….Hugo [Chavez] set the military and the National Guard to crack down on any smuggling of food…But the price controls led to shortage of food as suppliers could no longer afford to import necessary goods which put increased stress on domestic production…This has led to a growth in black marketing where in even engineers and lawyers are smuggling goods like pasta and petrol across borders…

Chavez persuaded the Venezuelan legislature to decree the 2011 Law on Fair Costs and Prices, which actually made inflation ‘illegal’. A newly created ‘National Superintendence of Fair Costs and Prices’ was empowered to establish fair prices at both the wholesale and retail levels. Companies that violated these price controls were to be subjected to fines, seizures and expropriation.

This led to massive hoarding up of necessities like toothpaste, toilet paper with people buying up 12 packets (4 rolls each) in one go. Such trends saw the supermarkets being emptied out even before stockers could get in the supply…

In 2014, Chavez’s successor Nicolas Maduro passed the Fair Prices Act through which it banned profit margins above 30% and chalked out prison terms for offenders of hoarding and over-charging….Maduro sent out inspection teams comprising of inspectors, lawyers, military personnels to check on the ‘fair prices’…In one day alone, around 331 audits were held…Strict measures to check irregular invoices, speculative profit margins and missing price tags during the Christmas shopping period, were put in place.

And so on. Obviously, this increasingly comprehensive and vigorously enforced price control regime did not have anything like the intended effect. Inflation bumped along under Chavez at about 20-30% a year, then exploded under Maduro:

This hyperinflation was a big part of why Venezuela suffered the most stunning and utter economic collapse in recent world history. The stories out of the country belong in a post-apocalyptic novel.

The utter failure of Venezuelan price controls should also serve as a reminder that there are real-world factors that don’t appear in macroeconomic models — for example, the black market. In the U.S., a vigorous, comprehensive regime of price controls would undoubtedly cause people to turn to cryptocurrency, and to technologies like the dark web, to evade the controls.

Anyway, I don’t want to present this history as if it adds up to a slam-dunk, airtight case that price controls never work as an inflation-fighting policy. In fact, history is hard to interpret, theory involves lots of assumptions, and macroeconomists have been largely derelict in their duty of studying inflation in recent decades (though I predict this will change quickly now). We don’t know for certain that price controls can’t work as an inflation-fighting tool.

But that said, as things now stand, the balance of evidence certainly looks to be against this tool. There are multiple obvious downsides and potentially catastrophic possible downsides. That’s why until we know more — which will be decades from now, and will involve a lot of careful research effort — we should avoid using price controls to fight inflation.

Update: Isabella Weber has an excellent Twitter thread in which she talks about the uses and abuses of price controls, and clarifies what she thinks their scope should be. In this tweet, she echoes my own reservations about price controls:

Very balanced and informed summary of what we know and don’t know. An additional thought. If the relatively moderate inflation we have now, significantly affected by supply side disruptions that may be easing, legitimizes the retreat from extraordinary monetary ease, there may be a positive consequence. The massive accumulation of excess reserves and negative real risk-free rates has encouraged both leveraged recapitalizations of established businesses and the flood of “nontraditional” capital into illiquid ventures at unsustainable valuations, as well as the crypto bubble. This extreme, speculative financialization of enterprise both raises Minsky-type macro-financial risk and distorts the potential for productive speculation. Enough is enough, if not too much

Solid article on the theory and history of price controls, particularly in the context of inflation. I also think that we should keep in mind that a significant driver of inflation is the shift in consumption of services to goods. [1] It’s expected that the higher demand for goods will lead to a short term increase in prices and further we’d expect the goods/service balance to normalize as the pandemic hopefully wanes over the coming year. Price controls would largely only shift consumer preference from price controlled (i.e., rationed) goods to alternative goods that aren’t yet price controlled and simply change the specific goods experiencing inflation.

I’d also recommend Joseph Politano’s recent article, “Are Rising Corporate Profit Margins Causing Inflation?” [2] (It’s free). That article analyzes corporate profits to show that there isn’t any evidence that our current inflation corresponds to increasing corporate profit margins. E.g., despite higher car prices, car manufacturers have actually had a decrease in profits due to component shortages constraining volume and increased costs.

Politano also points out that the US’s WW2 Office of Price Administration had 160,000 employees at its peak. It would not be feasible for the US to legislate and build a comparably large government org in time to address our current inflation controls. Further, our modern economy is far larger and complicated, with substantial foreign firm integrations.

[1] https://twitter.com/mattchagy/status/1466900351861211137

[2] https://apricitas.substack.com/p/are-rising-corporate-profit-margins