Why do economists get paid more than sociologists?

An economic explanation.

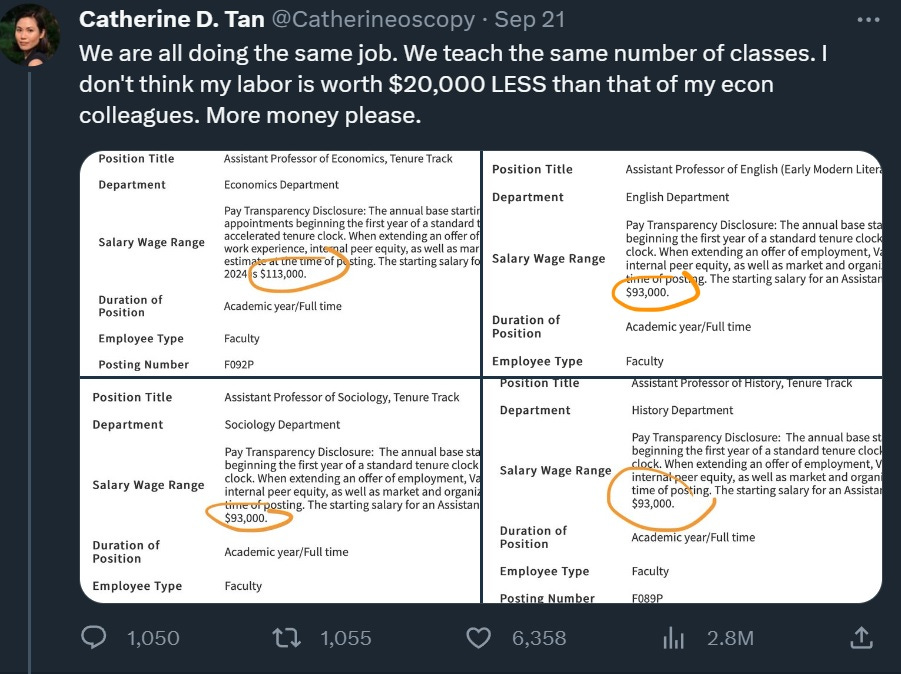

The other day, Vassar College sociologist Catherine Tan complained about the fact that her econ professor colleagues made higher salaries than sociologists, historians, or English profs:

Now, the phenomenon of someone who makes 2.3 times the U.S. median personal income complaining about the salaries of people making 2.8 times the U.S. median personal income is an interesting one. It probably points to some important sociological (or psychological) phenomena — who people compare themselves to, what jobs they think are equivalent, how money conveys status, and so on. But as interesting as all that stuff is, today I just want to talk about the actual question — why economists make more money than sociologists.

Tan is certainly not the first to observe the disparity. Fourcade, Ollion, and Algan (2015) noted that economists make considerably more than sociologists or English profs, and perhaps only slightly less than engineering profs:

There are various other data sources, some of which put sociologists higher on the salary ladder, but they all have economists ahead. The question is why.

Economists and sociologists are going to have different answers to that question, because they analyze the world in different ways. Sociologists might explain salary differences as a function of power, or relationships, or cultural values. But economists would tend to explain salary differences in terms of supply and demand.

The supply and demand for economists and sociologists

First, let’s quickly review what “supply” and “demand” are. If you know this, you can skip down to the next section

In casual conversation, people use “supply” to mean “how much gets sold”, and “demand” to mean “how much gets bought”, or something along those lines. But in economics, supply and demand are actually just hypotheticals. Supply is how much sellers would hypothetically sell at a given price, while demand is how much buyers would hypothetically buy at a given price.

Obviously there are lots of hypotheticals we could throw out there. How much pizza would you eat if a pizza cost $10? How much pizza would you eat if a pizza cost $20? And so on. So we can represent all of those hypotheticals as a curve (or a straight line, because drawing curvy lines in Microsoft Paint is annoying, and I don’t own an iPad).

So as an example, maybe the supply and demand for sociologists looks like this:

I drew the demand curve as just a straight up-and-down line, for the sake of simplicity. What this means is that universities decide they’re going to hire a certain number of sociologists, and they just hire that number, no matter the price. Obviously that’s unrealistic — if sociologists insisted on salaries of $15 million each, universities would probably not hire very many. But for the purposes of this simple example, let’s just assume that Vassar University says “OK folks, we have to fill 6 tenure-track sociology positions this year, so we’ll pay them whatever we need to.”

Now let’s think about the supply curve. It slopes up. What this means is that hypothetically, the more sociologists get paid, the more people will want to be sociologists. If sociologists got paid $400k a year to start, a ton of people would be getting sociology PhDs and competing for those spots. If sociologists got paid $15k a year, people would avoid that job like the plague.

OK, so that’s what supply and demand curves are. They’re just hypotheticals. But the point where the two curves meet is not a hypothetical; it represents the model’s actual prediction of what actually happens. When the universities offer the level of salary that sociologists require in order to fill the universities’ yearly quota, it’s a done deal, and the sociologists get hired, and that’s that.

This is just about the simplest possible model of a market, but it immediately lets us think about possible reasons why economists might get paid more than sociologists. There are both supply-based and demand-based reasons why economists would get paid more.

The supply story

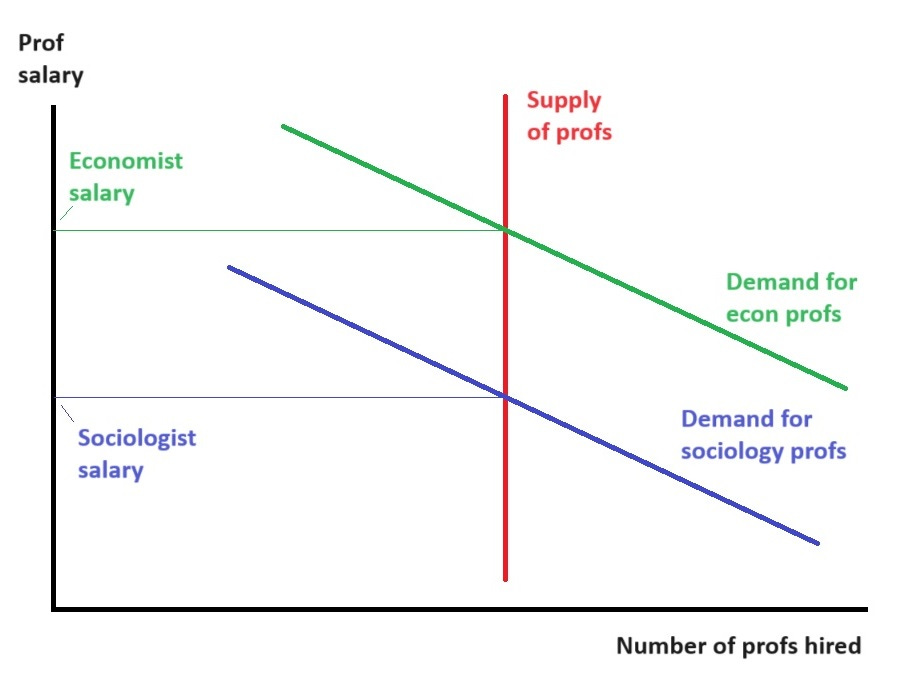

Suppose that universities hire the exact same number of economists and sociologists. But suppose that economists have a lower level of supply. That means that for any given salary, fewer people want to be economists than sociologists.

If that’s true, the graph looks like this:

If fewer people want to become economists than sociologists for any given salary, but universities just insist on hiring as many as they need to, then economists get paid more than sociologists, because you have to pay them more, otherwise people won’t do the job.

Why might you have to pay people more to become economists than to become sociologists? Well, maybe being an economist just isn’t as nice. You have to put up with some jerks, the papers are a bit longer, you have to take more math classes (which Americans hate), and the subject matter is a bit more dry. So maybe economists get paid more because the job is worse!

This is called a “compensating differential”. I don’t actually think this explains much (or any?) of the economist salary premium, but it’s useful to think about, because it illustrates the unintuitive principle that when people are less eager to do a job, you have to pay them more to do it.

A more realistic explanation, I think, is that the people who are considering becoming economics profs have a lot more outside options. Economists tend to feel favorable toward the private sector — after all, a lot of economics theory is about how the private sector is great. So people with econ PhDs might consider academia, but be almost as happy to go be consultants, or data scientists, or private-sector economists working for Amazon. Whereas sociology PhDs might be more likely to have their heart set on a career as a scholar.

Another reason economics PhDs might have more outside options is that their skills might translate more easily to a high-paying private-sector job. Though sociology has increased its statistics acumen in recent years, econ still generally requires learning more advanced stats (or “econometrics”, as they call it). That can make it easier for economists to transition into data science roles. When some economist friends of mine decided to go into data science and went to a boot camp for PhDs, they found that the statistical methods weren’t too different from what they had done as academics. Whereas for many sociologists, especially those who do more qualitative research, it probably requires more retraining to make that jump.

Also, the private sector simply hires a lot of economists to do actual economics. Susan Athey and Michael Luca wrote a fairly detailed description of what tech companies hired economists to do as of 2019. Here are some excerpts from a recent article about Amazon hiring PhD economists:

Amazon is now a large draw from the relatively small talent pool of PhD economists, which in the United States grows by about only 1,000 new graduates every year…In the past few years, Amazon has hired more than 150 PhD economists, making it probably the largest employer in the field behind institutions like the Federal Reserve, which has hundreds of economists on staff…

[A]ccording to background interviews and Amazon itself, integrating economists has been critical to the company’s phenomenal growth in e-commerce…Amazon’s economists game out real estate decisions, set the lowest prices that will deliver a profit, precisely determine what customers care about and whether advertisements are working[.]

You just don’t see that sort of direct application of sociology research in high-paying private-sector jobs. A lot of people with PhDs want to get a job doing research in their chosen field of study; it’s a lot easier to do real econ research in the private sector than real sociology research.

All these outside options naturally make young econ PhD graduates more reluctant to take a job as a prof. Why get paid $113,000 or even $180,000 to go work as an assistant prof when you can go do real, substantive economics research at Amazon — and even see your theories immediately tested in the field! — while making $245,000? Of course PhD students are taught to love academia, so many will still go be profs instead of taking the higher private-sector salary. But the existence of all those tasty outside options probably forces universities to sweeten the deal a bit.

So that’s the supply-based explanation for higher economist salaries. Essentially, it’s very plausible that economics PhD grads aren’t as eager to be profs as sociology PhD grads, forcing universities to sweeten the deal for economists with cash.

The demand story

Alternatively, it’s possible to tell a somewhat plausible story based on higher demand instead of lower supply.

For this section, suppose that the number of people who have made up their minds to become sociology profs is fixed, and that the number of people who have made up their minds to become econ profs is also fixed, and that they’re the same number for each. So supply is now just a vertical line.

And now suppose that universities are more desperate to hire economists than they are to hire sociologists. This would mean, for example, that a university would be willing to pay more to hire 6 new econ profs than to hire 6 new sociology profs. That would look like this:

Why would universities be more desperate to higher econ profs than sociology profs? Well, one reason could be the very high demand for economics classes from undergrads. Business majors take a lot of economics classes, and business is a more popular major than all of the social sciences put together:

If a university doesn’t have enough econ profs to teach that massive horde of business majors, they could be in big trouble in terms of their ability to recruit undergrads (or, cynically, to charge those undergrads high tuition). Whereas if they don’t have enough sociology profs, they might be in only modest trouble. So it’s plausible that they’re willing to pay more to secure their quota of econ profs — allowing econ profs to charge them more.

In my view this is probably less plausible than the supply story, simply because it’s a lot more complex, and requires more assumptions about what universities want. But it’s still worth mentioning.

So what’s actually the true story?

The simple theories I sketched out above are how most economists probably think about the salary differential among academic fields. Sociologists might disagree, and use a completely different theoretical framework with lots of different assumptions. How would we tell which one is right?

Well, the answer is “empirics”. Theory might differ between sociology and economics, but data and statistical methods look much the same. Ideally, we could test competing theories of salary gaps and see which can explain the data better (and more parsimoniously).

In reality, that’s going to be a tall order. Even if we knew that supply-and-demand was the correct model here, it would be hard to match the theory to the data. Remember that supply and demand curves are purely hypothetical; the only thing that actually happens is that one little point where they meet. That’s all you get to see. So in the real world, identifying supply and demand curves requires lots of assumptions and is generally really hard. Of course, it’s probably going to be even harder to get a clean empirical test of sociology theories, especially theories that are written in words rather than equations.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, of course. There are lots of innovative ways people use to try to estimate supply and demand curves — natural experiments, surveys, pricing experiments, and so on. And as sociology becomes more empirical, it will also get better at specifying and testing its theories. So I actually think we’ll learn more about why exactly economists get paid more than other social science academics.

In the meantime, one way to test whether or not salaries are determined by market forces or social ones is to simply try demanding more money from universities. Catherine Tan’s concluding line — “More money please — represents an approach that is far more likely to work if salaries are socially determined than if they are set by markets.

And it’s perfectly possible that that approach will work, at least at some universities. After all, there are plenty of examples of universities seeming not to be purely rational cost-minimizing entities. For example, a ton of college sports programs lose money, but students and alumni both love them, so colleges spend a lot on them. It seems unlikely that Ibram X. Kendi’s Center for Antiracist Research would have received tens of millions of dollars in funding based entirely on ruthless considerations of dollars and cents.

In the meantime, though, consider the possibility that market forces — things like professors’ outside options, demand for undergrad majors, etc. — are also potentially very important. Universities can fight market forces if they want to, but it’s expensive and difficult. Paying economists a little bit more than sociologists may simply be the path of least resistance.

Can vouch that as an undergrad at Reed about fifteen years ago, I watched this very drama play out on campus. I came in watching the tail end of a second failed faculty search for an Economics professor where Reed tried to maintain equal faculty pay across all disciplines, and after receiving feedback from the candidates that declined the position who said they were offered more $$ elsewhere, they began a third search with a substantially higher salary offer, much to the immense and vocal displeasure of several of my professors in the Sciences (and I imagine other disciplines as well…).

I think it's very weird for sociologists or liberal arts professors to fixate on economics professors' salaries when lots of other fields get higher average & median salaries. The argument (see https://twitter.com/JessicaCalarco/status/1704894737172627659 for example) that it's all about economists' government positions and status seems very odd to me when you look at all the other disciplines that also get paid more. I don't think "accountant" is a super prestigious title--the field is (unfairly) a shorthand for a boring, soulless job--but professors of accounting make substantially more than most economics professors.

Some of the responses and alternative explanations sound more like cope than a serious attempt at explaining wage differentials, which is also slightly odd because I don't think most sociologists secretly wish they were working at Amazon or an investment bank, so "economists have outside options at <insert evil firm here>" seems like it would satisfy a lot of people's egos, but I guess not in the way they wanted?