Why aren't wages rising in a tight labor market?

A macroeconomic mystery with important consequences.

Why do people hate inflation? Traditionally, economists just shrugged at this question. If a dollar is worth less, who cares? If your salary doubles and all the prices double, is anything really different? Yes, the value of your (dollar-denominated) savings and/or debt will change, but across the whole economy this will cancel out. So why does inflation send voters into such paroxysms of rage?

In fact, I wrote about this about a year and a half ago, when high inflation had just begun:

The answer, it turns out, is that people hate inflation because they think it makes their wages go down. Instead of “your salary doubles, and prices double, so who cares”, it’s “prices double, but your salary only goes up 1.5x, so now you’re poorer than before”.

And in fact, people look pretty right about this. Here’s real average hourly compensation over the years. You can see that while the inflationary periods — the 70s and the early 2020s — aren’t the only times that wages stagnate or go down, they definitely are bad times for wages.

This is kind of a weird mystery, but first let’s take a minute and rebut some of the folks who claim wages have actually risen in this inflationary era.

Yes, real wages have fallen during the big inflation

In 2021, some economists on the more progressive side of things argued that real wages were rising at the lower end of the scale. But not all data sources agree, and by late 2021 it was clear that real wages were falling across the board as inflation continued. Here’s data from the Atlanta Wage Tracker showing 3-month median wage changes for each quartile of the wage distribution, adjusted for the 3-month change in the CPI:

You can see how unusual the current period is. People are used to seeing their real wages go up most of the time, and any dips are small and short-lived. The inflation of 2021-22, however, has seen huge and sustained decreases in real wages across the board. Interestingly, real wages on this graph have returned to growth in the last month, due to a two-month drop in energy prices that led to a flatlining in short-term measures of headline inflation. But this just drives home the point — namely, it sure looks like real wage growth is driven by inflation, at least in the short term.

In fact, there are still some people who try to argue that wages are actually up in the inflationary era. Paul Krugman wrote a Twitter thread to this effect the other day:

Well, not really. First of all, when you compare to March 2020 — when significant numbers of recorded Covid cases began, along with social distancing measures — you find that real average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers are actually down since the start of the pandemic. But that’s just a nitpick. The much bigger point is that sustained, rapid inflation didn’t start until 2021. By choosing “pre pandemic” as his starting date, Krugman includes the burst of deflation that we had in April of 2020, and the big increase in real wages that seems to have resulted from that.

In other words, it really looks as if inflation is pushing real wages around in the pandemic era. When inflation was negative, real wages surged. When inflation was high, real wages fell.

In fact, this looks like it’s not just a U.S. thing — it’s true in other countries as well. For example, Australia:

So the common belief that inflation makes workers poorer appears to be very right, at least in the short term. And so it makes perfect sense that people are mad about inflation — no one likes to get poorer, month after month!

But the larger question here is: Why?? Why does inflation make wages go down? In fact, this is a major macroeconomic mystery.

Why does inflation make real wages go down?

First, let me explain why this is such a mystery. The real value of labor isn’t the number of dollars you can get from an hour of work; its the amount of real, valuable stuff you can buy from an hour of work. And there's nothing about inflation — which is just a decline in the value of a dollar — that should change the real value of labor, any more than it should change the real value of rutabagas or Netflix.

Instead, economists think the real value of labor should be determined by supply and demand. If the economy is booming and unemployment is low, that means demand for labor is high, which should push up real wages. And unemployment is quite low — 3.7%, the lowest it’s been since 1969. The same is true of broader measures like U6. And my favorite measure of labor market strength, the prime-age employment-population ratio, is right around 80%, which is just about as high as it gets in any economic boom except for the late 90s.

There are some other indicators that also suggest that employers are desperate to find workers:

So with all these companies trying very hard to attract workers, why aren’t they bidding up the real price of labor? Why is labor getting less valuable in real terms, even as employers are clamoring for workers?

One possible reason is that salary negotiations don’t happen that often. If wages and salaries can only go up once a year, then maybe wages were set before people realized how high inflation would be. This explanation may have made sense a year ago, but high inflation has been going on for a year and a half now. A year and a half is definitely enough time for workers to renegotiate their wages to adjust for high inflation. So I don’t buy the “infrequent wage setting” explanation.

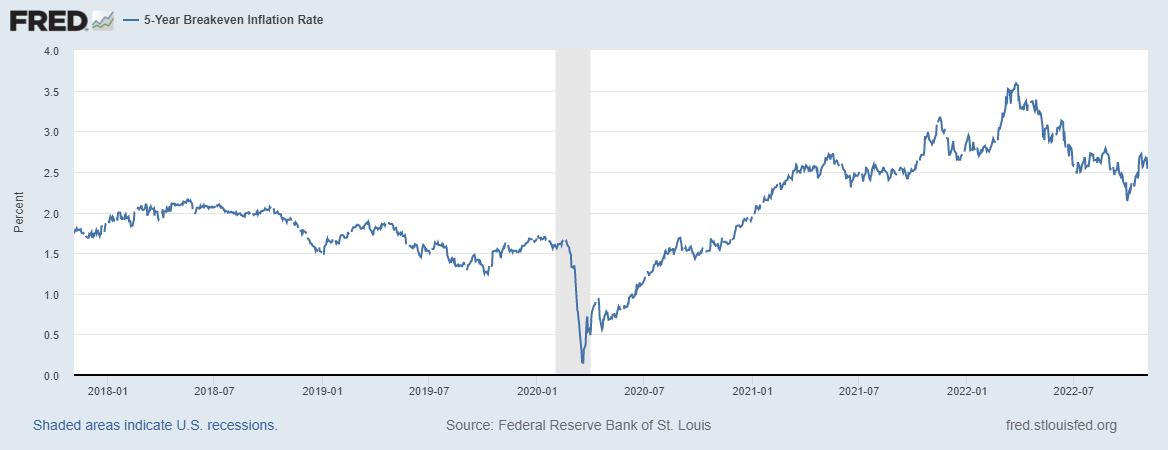

Another possible reason is that everyone keeps expecting inflation to be transitory. If both employers and employees think inflation is going to die down in a couple months, maybe they’ll keep getting surprised when inflation fails to die down, with the result that wages keep undershooting inflation. And indeed, even as inflation went to 8%, 5-year inflation expectations never went above 3.5%, and are now back at 2.5%.

So maybe workers are getting screwed because they keep playing for Team Transitory. In fact, markets (which are driven by finance people rather than workers) tend to be pretty bad at predicting actual inflation, so this kind of consistent human error seems entirely reasonable. And this also fits with the experience of the 1970s — real compensation fell in the first oil shock (1973) and the second oil shock (1979), but rose a little bit in the mid-70s even though inflation stayed high. Maybe expectations caught up to the reality, and workers started demanding consistent cost-of-living increases. And maybe that will happen now if the current inflation drags on for another year.

But it’s still just a big strange to attribute what looks like a pretty consistent effect (of inflation on real wages) to consistent errors in human judgment. Why do workers keep expecting inflation to undershoot the reality, in era after era, in country after country? It seems likely that there’s more to this story.

In economics jargon, what we should be looking for are sources of upward nominal wage rigidity — things that make it hard for workers to bargain for higher wages. There’s lots of research on downward wage rigidity — things that make it difficult for employers to cut wages. But downward wage rigidity implies that workers have some bargaining power. Upward wage rigidity implies that the balance of power is on the employer side, at least sometimes.

Also, there is little direct evidence of upward nominal rigidity in the data on wage changes. Wage cuts are rare but raises are common. So if there’s upward wage rigidity, it’s more likely to be real wage rigidity. When Robert Shiller talked to people about why they don’t like inflation, this is basically what people told him.

There are certainly theory papers that posit the existence of real wage rigidity in both the upward and downward directions. On the empirical side, however, I can’t find much evidence, and the few papers I can find are a bit conflicted on whether or not upward wage rigidity exists. Nor can I find many papers delving into the possible sources and mechanisms of upward wage rigidity.

This seems like an important topic for macroeconomists to research. If upward real wage rigidity exists, it changes how we should think about inflation. It would mean that inflation consistently takes income away from workers and hands it to capital owners. In addition to being unfair and reducing social welfare and making most people really mad, that will also tend to hurt economic efficiency (because it distorts the relative prices of the factors of production). So if I were a macroeconomist, this would be a topic I’d look into.

Meanwhile, the Fed has to decide what to do about the current inflation — whether to keep raising rates, or to back off for fear of a recession. If inflation consistently reduces real wages, that biases things toward the “keep hiking rates” side of the debate. It means that a short spell of higher unemployment that brings inflation back to low levels might be the best way to raise real wages in the medium term.

That’s very contrary to typical economic intuition — usually, we think that unemployment lowers wages because it decreases labor demand. But in a world where high labor demand coexists with falling real wages, we need to start to ask ourselves whether the standard intuition is just wrong.

Upward nominal wage rigidity is so obviously a thing, I can't believe anyone would discount it. I have unique access to this phenomenon, as a Professor (top rank) at a 3rd-class public non-research university. Faculty salaries here do not have cost-of-living adjustments. Once we have reached the top rank (I call myself a "gargoyle") we are both 100% job-locked (no other university in its right mind would hire any one of us) and subject to the results of union negotiations. Our paychecks might be the same for years on end, unless the union can negotiate an increase here and there. The union can point to inflation and beg and plead, but the idea that they could ever win a 10% increase in a single year is laughable. 3% per year for 3 years is considered a huge win.

Interesting piece. And although I agree with Noah that it seems highly likely there's probably something deeper at work (that economists need to research), I was intrigued by this sentence:

>>Another possible reason is that everyone keeps expecting inflation to be transitory.<<

The above rings credible to my ears, although I might be tempted to replace "expecting" with "hoping." It's a royal P.I.A. to switch jobs. In some cases doing so means moving to a different city. Perhaps a super expensive one. In many cases (yes, even in this age of remote work) it entails screwing up your commute. And who wants to move when you've got a good deal on rent or your kids are happy in school? There's also spousal income to consider, which has been linked to a general decline in employment-related geographic mobility.

Plus, there's this: for most workers I'd imagine that "amount of time with an employer" correlates positively (almost by definition) with job security. The employee who has been working for a given employer for (say) nine years is understandably going to be nervous about making a move to a job where the long term prospects for stability are questionable. This is all the more true given the fact that, in the US at least, it wasn't all that long ago that underemployment was a persistent, nagging problem (and indeed we had a scary episode of *mass* unemployment only 2.5 years ago!). So a lot of workers have vivid memories of a recent, weaker job market, and thus they're understandably hoping for the best in terms of their own wages rather than getting into a situation characterized by less job security that increases the risk of joblessness.