Why America fell behind in drones, and how to catch up again

A guest post by Cat Orman and Jason Lu

Most discussions of industrial policy in the U.S. focus on semiconductors, batteries, or electric vehicles. But there’s an incredibly important industry where the U.S. has fallen badly behind, and where its deficiencies could cost the U.S. Military its edge over China. I’m talking about drones.

I’ve been banging the drum for a decade about the crucial importance of drones for modern warfare, but I’m no expert in the field. So I got Cat Orman and Jason Lu, the cofounders of Flyby Robotics — a startup developing American-made drones — to write me a guest post on the topic. It’s important stuff.

Financial disclosure: I have no financial stake in Flyby Robotics, or in any related company or fund.

Last month, the House of Representatives passed a bill that would ground over 70% of America’s industrial drone fleet. The Countering CCP Drones Act seeks to ban DJI, a Chinese unicorn and the world’s largest commercial drone manufacturer, from supplying its drones in the United States. So why has the bill sent drone pilots into a panic? Here is the unfortunate truth: there is no real alternative to DJI.

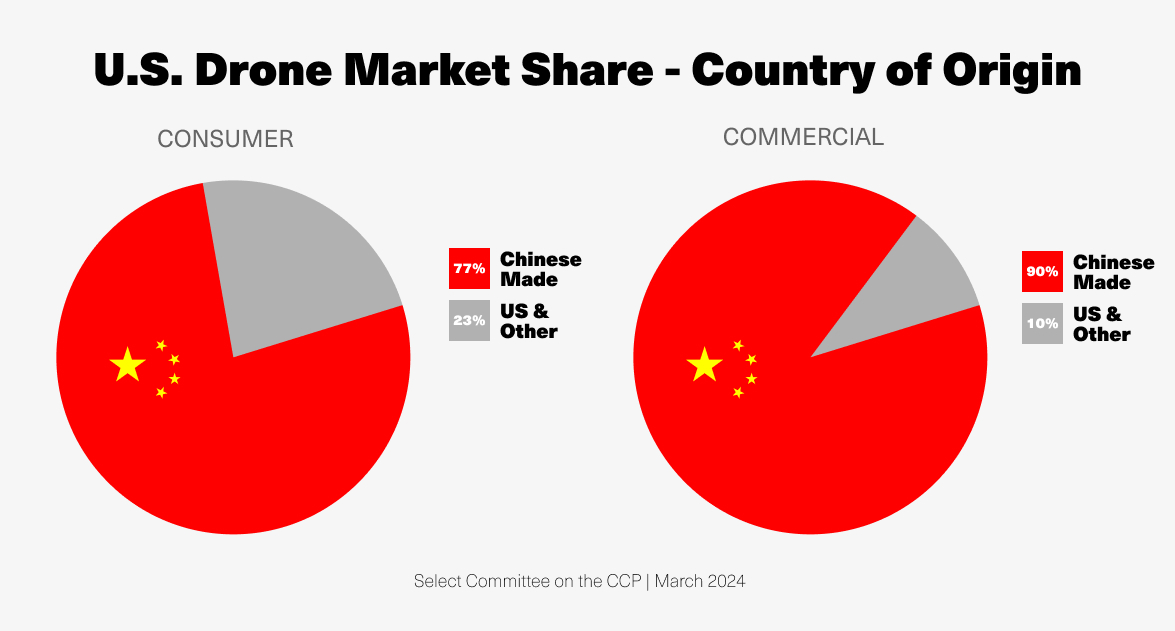

Like much of our electronics, the majority of drones deployed in the United States are made in China. It’s a bigger hole in our industrial base than you might think. Drones operate behind the scenes of every American industry — they inspect our civil infrastructure and electric grid, shoot movies, conduct land surveys, detect diseases in crops, prospect for minerals, locate gas leaks, and create 3D models. If you get mugged in one of over 1,500 American police precincts (including Santa Monica, where I live), the first responder on the scene might be a drone. But — as the war in Ukraine has demonstrated — even commercial-grade drones will play an increasingly important role in national security. To protect our critical industries and field an effective fighting force, the United States must develop a competitive drone industry, then get DJI out of our airspace.

A Brief History of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS)

The Countering CCP Drones Act was prompted by concerns that Chinese-made drones could be used to leak data on our critical infrastructure vulnerabilities back to a foreign adversary. DJI has already been accused of sending sensitive information to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). According to the FBI, the use of DJI drones "risks exposing sensitive information to PRC authorities [and] jeopardizing U.S. national security". As tensions with China rise, we cannot afford this vulnerability — both a serious cybersecurity risk to our critical industries and a commercial dependency that could be cut off at any time.

So why hasn’t the United States developed its own drone industry?

It’s a little-known fact that the United States pioneered the use of drones in the mid-20th century, first as target practice for the Army in the 1940s, then for photographic reconnaissance in Vietnam. American primes General Atomics and Northrop Grumman have dominated multimillion-dollar long-endurance systems like the Predator and Global Hawk since they were deployed over Bosnia in the 1990s. But when drones evolved from eight-figure military jets to commercial quadcopters, the United States lost its edge.

A decade ago, the commercialization of this military technology was a promising capability of the future. “Consumer” drones were largely targeted towards hobbyists with home-assembly kits, and dedicated startups were just gaining traction. In 2010, Parrot, a French electronics company, debuted the AR.Drone, the first-ever smartphone-controlled system, at CES. In 2014, 3D Robotics (3DR), founded five years earlier by a 20 year old tinkerer and the editor-in-chief of Wired, released the Iris+ and the X8 Android-controlled quadcopters aimed for hobbyists with GoPros. But these drones were effectively toys. They couldn’t reliably produce quality video, even by consumer standards, and they were nearly impossible for the average person to fly. With no ability to maintain a stable position, even a slight breeze could render footage unusable. With crash landings so frequent, systems couldn’t make the leap to mass-market.

The king of the consumer drone market was made in 2013, when DJI released its flagship product. Founded in 2006 by Frank Wang in a Hong Kong University of Science and Technology dorm room, DJI had released a couple of hobbyist quadcopters, but the Phantom 1 was its breakout hit. A $629 dinner plate-sized drone with four motors arranged in a distinctive white body, the Phantom had the stability to take professional-quality footage every time, and required little to no training to pilot it successfully. The drone market ballooned from a small community of nerds to anyone who wanted to shoot personal footage, or even professional film. It was an inflection point — suddenly, drones had real consumer utility.

Frank Wang was obsessed with hardware, and the Phantom 1 was in a class of its own. DJI crafted custom components, from motors and gimbals to advanced avionics ensuring that everything the customer cared about was in their control. DJI got three things right:

Reliability: the failure rate was extremely low.

Video transmission: users got crisp 1080p video even at a distance of about 1000’. Gamechanger.

User experience: extremely easy to fly.

Two years after the Phantom hit the market, the first American competitor came out. 3D Robotics released its 3DR Solo, marketed as the first “smart drone” and priced at $999.95. But competing with China in a sub-$1,000 market is a losing game — labor and component costs in Shenzhen are simply unmatched elsewhere. Solo reduced its price to $799.95 a year in, but couldn’t keep up with the $629 Phantom.

That same month, DJI would receive another unfair advantage. On May 19th, the State Council announced Made in China 2025, a ten-year action plan designed to make the nation a manufacturing superpower. The plan focused on developing China’s industrial base, transitioning from the world's factory of cheap, low-quality goods into a leader in high-tech manufacturing. Alongside BYD, Huawei, and Autel, DJI was named a champion of the initiative. Through Made in China 2025, the PRC earmarked hundreds of billions in funding to build up advanced technology companies. Leveraging these subsidies, DJI and Autel, another Chinese drone manufacturer, were able to artificially cut prices to dump cheap systems on the American market. The United States, in observation of a free and competitive international marketplace, did not match these subsidies; American drone companies struggled to survive.

Notably, not all of DJI’s funding came from the Chinese government. Foolishly, in retrospect, the growth of the Chinese drone industry was, in part, fueled by American venture capital. In 2014 and 2015, Sequoia and Accel made major investments in DJI, collectively exceeding any funding for 3DR, Airware, or any other American drone manufacturers. With CCP subsidies and American capital, DJI would continue to dominate the global market. Naturally, a mass-extinction event for U.S. companies followed. In 2016, 3D Robotics shut down its drone manufacturing business line, and Airware, a leading American enterprise drone manufacturer, closed its doors in 2018.

However, one American company was lucky enough to enter the market just after this bloodbath. Skydio, founded in 2014, sought to build and deploy drones for enterprises, not consumers. Critically, like DJI, the founders of Skydio were hardware-obsessed, prioritizing reliability and user experience. They launched their first product, the $2,499 R1, in February of 2018. Just years earlier, there was no enterprise market to speak of — use cases had been discussed, but there was still a large gap in educating end-users on what drones could do for their business. By 2018, experienced drone operators had begun to connect the dots; roof inspection, land surveying, and search and rescue were all early use cases. In fact, commercial awareness grew so much that when the Skydio 2 launched in 2016, it was an immediate hit.

Just as this enterprise market was taking off, President Trump was getting increasingly “tough on China”. Suddenly, the idea that tensions could escalate and Chinese-made drones could become weapons of war became very real. In 2017, the U.S. Army grounded DJI drones following an internal memo citing cyber vulnerabilities. Three years later, the Department of the Interior grounded over 800 DJI drones used for conservation, and the Commerce Department added DJI to its “entity” list, restricting it from buying US-made technology or parts. No longer were drones merely fun consumer toys; they were now industrial tools that presented glaring national security vulnerabilities.

With enterprise-level drones now deployed over cities and inspecting power plants, regulators grew increasingly concerned. Mesh radio, LTE connection, and machine learning further enhanced the efficacy of drones, creating unacceptable risks if they were under any form of control by a foreign adversary. It was these factors that made the gap of American-made drones painfully apparent. Something had to be done.

Small Drones on the Battlefield

Just over twelve months after the DJI Phantom hit the market, Vladimir Putin annexed the Crimean Peninsula. By this time, a small community of tinkerers, pilots and developers had already sprang up around quadcopters — a minute but growing number of dedicated hobbyists knew how to, for example, add a special payload to a drone. Ukraine couldn’t purchase military equipment from foreign governments who were then still unwilling to provoke Russia, and had little money to spend.

But cheap consumer-grade drones allowed Ukraine to leverage its wealth of technical talent to develop a homegrown military capability. In the spring of 2014, Ukrainian volunteers crowdfunded and sourced two Phantom 2s, one Skywalker X8, and one Oktopcopter, all commercial off-the-shelf drones, for the Ukrainian Army. Ukrainian battalion commander Natan Chazin founded the Aerozvidka Project, which by 2015 grew to a 20-man tactical unit of repurposed vans launching modified hobby drones.

Artem Vyunnik, who had been building a consumer drone company at the time of the invasion, modified his prototype into the fixed-wing A1-CM “Fury” for military use, which was quickly adopted by the National Guard and the Armed Forces. Ukrainian drone pilots founded UKRSPECSYSTEMS to build new military drones from scratch out of commercial components, and quickly developed the PD-1 “People’s Drone”, also a fixed-wing system, capable of 6-hour flights. Companies rapidly iterated on combat drone models in conjunction with the armed forces, and produced around 30 different models of drone that were officially used by the Ukrainian army in the first three years of the war. In 2018, a U.S. Army National Guardsman advising the Ukrainian Delta Center told The Smithsonian that “In the last two years . . [The Ukrainians] have rapidly advanced from using dirigibles or balloons to do reconnaissance to building their own UAV systems . . . from zero.”

Ukraine’s successful deployment of its drone industry after the 2022 invasion needs no introduction. Since then, armed forces across the globe have increasingly deployed small UAS for ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance), munitions delivery, as well as electronic warfare. In August 2023 Department of Defense DoD Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks announced the Replicator Initiative, earmarking $1 billion to field thousands of low-cost unmanned systems for the U.S. military.

Simply put, small unmanned systems allow warfighters to complete missions too dangerous for human soldiers, at a dramatically lower cost. The U.S. Coast Guard, for example, calculated that it saved over $6.7 million in the last eighteen months by deploying small UAS instead of helicopters for vessel interception.

Building Drones in America

Drones, like most technologies we interface with today, are as much software as they are hardware. Interestingly, it was 3DR that kickstarted the open-source drone software ecosystem that would go on to power many Western-made systems. FC Cube, flight controller hardware originally designed for the 3DR Solo, was commercialized and sold separately, becoming the world’s most reliable — besides DJI’s. Today, FC Cube powers drones like the Matternet M2, a type-certified system that meets the most stringent standards set by the FAA for commercial use. 3DR also developed Ardupilot, an open-source autopilot software suite supporting a broad range of unmanned systems. Originally developed for internal use, Ardupilot has since ballooned into an open-source ecosystem with over 20,000 developers.

Of course, software alone would not cut it. Competing with China means also building hardware. In 2019, the United States National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for FY2020 — the annual bill funding our military — first included language banning the use of drones with electronic components made in China (today, also expanded to Russia, Iran, and North Korea.) Consequently, the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) created the Blue UAS list, a shortlist of drones with fully verified secure supply chains.

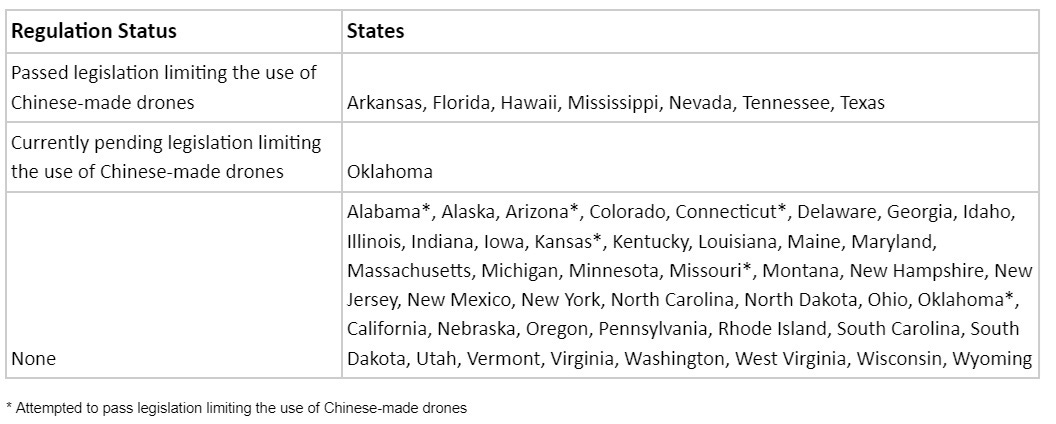

While Blue UAS and NDAA compliance is legally only relevant for Department of Defense procurement, many other areas of government have now chosen to follow these guidelines — but not all of them. Between 2010-2022, over 85% of drones purchased by state agencies were Chinese-made. Below is a table of various levels of state regulation as of July 2024.

While it might seem obvious to outright ban Chinese-made drones in American skies — we wouldn't allow Chinese planes flying over us — such heavy-handed regulation has consequences, too. The reality is that DJI builds the best drones, particularly when it comes to small-business applications. Today, no American-made system is as affordable and reliable, so it’s no wonder that many affected parties have loudly opposed an immediate ban. Moreover, DJI is no stranger to lawmakers — consider that they’ve out-lobbied Skydio nearly 3-to-1, spending $1.6 million just last year.

The Future of American Drones

Although the Countering CCP Drones Act excises the national security threat, it won’t catalyze a domestic industry that rivals DJI out of thin air. Truthfully, it will be challenging to compete with DJI, but with better technology, the United States can win. Where winning technologies coalesce will likely be different according to use case. At a high-level, drones are segmented by “group” according to their size and capability by the U.S. military:

Broadly speaking, drones range from small, cheap Group 1 systems (like military FPV kamikaze drones or commercial indoor inspection drones) to large, expensive Group 5 systems (such as the $30 million MQ-9 Reaper for high-altitude, long-endurance missions).

What matters most is not the price tag, but the cost per mission — how many missions can it be expected to fly before it is jammed or shot out of the sky? A $2,000 drone which flies one kamikaze mission effectively costs the same as a $20,000 drone which can be expected to survive 10 missions. Second is capability — can the drone support high-resolution sensor payloads? Can it deliver munitions? Does it have obstacle avoidance? As drones are deployed in a wider variety of applications, different size/cost/capability combinations own different use cases.

Eliminating CCP-sponsored drones from American skies is essential for our national security. But we will not accomplish a DJI ban by forcing American operators to use subpar systems. Pilots won’t stand for the ban until they have a viable alternative. That can only follow the development of a robust American drone manufacturing base. So how do we win? As the war in Ukraine has gruesomely illustrated, attritable systems are a key capability on the modern battlefield, and the United States should absolutely build up its own Group 1 companies. But the truth that inspired Made in China 2025 still holds — China is far better at making cheap products. We will likely not beat DJI purely on labor and component cost.

America has the advantage in advanced capabilities. The United States drone industry has succeeded in fostering a collaborative ecosystem of open-source software and hardware developers; companies like Aerodome, who builds drone-as-first responder software on top of off-the-shelf drones; and DroneDeploy, which supports reality capture. By acting as a platform and not competing with their customers, American drone companies can achieve the scale needed to drive down costs and compete with DJI. In the age of AI, a single low-cost drone with high-resolution sensors and a GPU can run a variety of software applications that can make it significantly more capable than a comparable Chinese system.

The United States must leverage its strengths in advanced software and open-source development to enhance the capabilities of affordable drones. Building a robust domestic manufacturing base — in military as well as commercial systems — is crucial for maintaining national security and technological superiority. By focusing on innovative solutions and collaboration within the industry, America can effectively compete with China and ensure that our skies remain secure and our defense capabilities remain unmatched.

What really made Skydio S2 successful was its superior obstacle avoidance and autonomous following capability- breath taking videos of snow boarders and mountain bikers using it to film themselves without anyone else helping. But the camera and wireless range still lagged DJI and most people aren’t interested in the autonomous following capability beyond toying around.

Skydio pivoted to industry, public safety and non weapon defense use cases (winning a large army situational awareness use case contract) and now sells the X10 which is too expensive for consumers but has closed the gap on photo sensor quality and still leads in AI compute / autonomous use cases.

It seems Skydio is poised to succeed in these areas, but currently has pulled out of the consumer market. Perhaps if they hit big enough they will have the luxury of reentering the consumer market.

The title says "how to catch up agaon". Is that supposed to be "how to catch Agaon, the dragonrider"?

Drone attacks seem like a good plot for season 3 of House of the Dragon.