Why $15 minimum wage is pretty safe

And why economists changed their minds on the minimum wage

When David Card and Alan Krueger came out with a landmark study in 1994 showing that a big minimum wage hike didn’t cause unemployment (as most economists predicted), Card was actively shunned by many of his colleagues, who were deeply invested in the theory that minimum wage kills jobs:

[E]conomists who objected to our work were upset by the thought that we were giving free rein to people who wanted to set wages everywhere at any possible level…I've subsequently stayed away from the minimum wage literature for a number of reasons. First, it cost me a lot of friends. People that I had known for many years, for instance, some of the ones I met at my first job at the University of Chicago, became very angry or disappointed. They thought that in publishing our work we were being traitors to the cause of economics as a whole.

Note that this opposition wasn’t just the anger of theorists who didn’t like having their favorite theories debunked by empiricists. The anger was partly political and ideological. The economists Card describes saw themselves as guardians of the free market, and viewed Card’s research as giving succor to advocates of command economies.

But over the next few decades, an interesting thing happened — empiricists like Card and Krueger began to take over the discipline of economics, while the scholars who recoiled at his minimum wage research became both rarer and quieter. And as the economics profession evolved, so did economists’ beliefs about the minimum wage.

The Shift

Actually there were really two shifts. Economists became more concerned with topics like inequality. Here’s a graph for the field of public economics (which deals with things like taxes and spending):

And thanks to computerization, empirical economics research steadily took over the field — becoming more credible and careful as it did so.

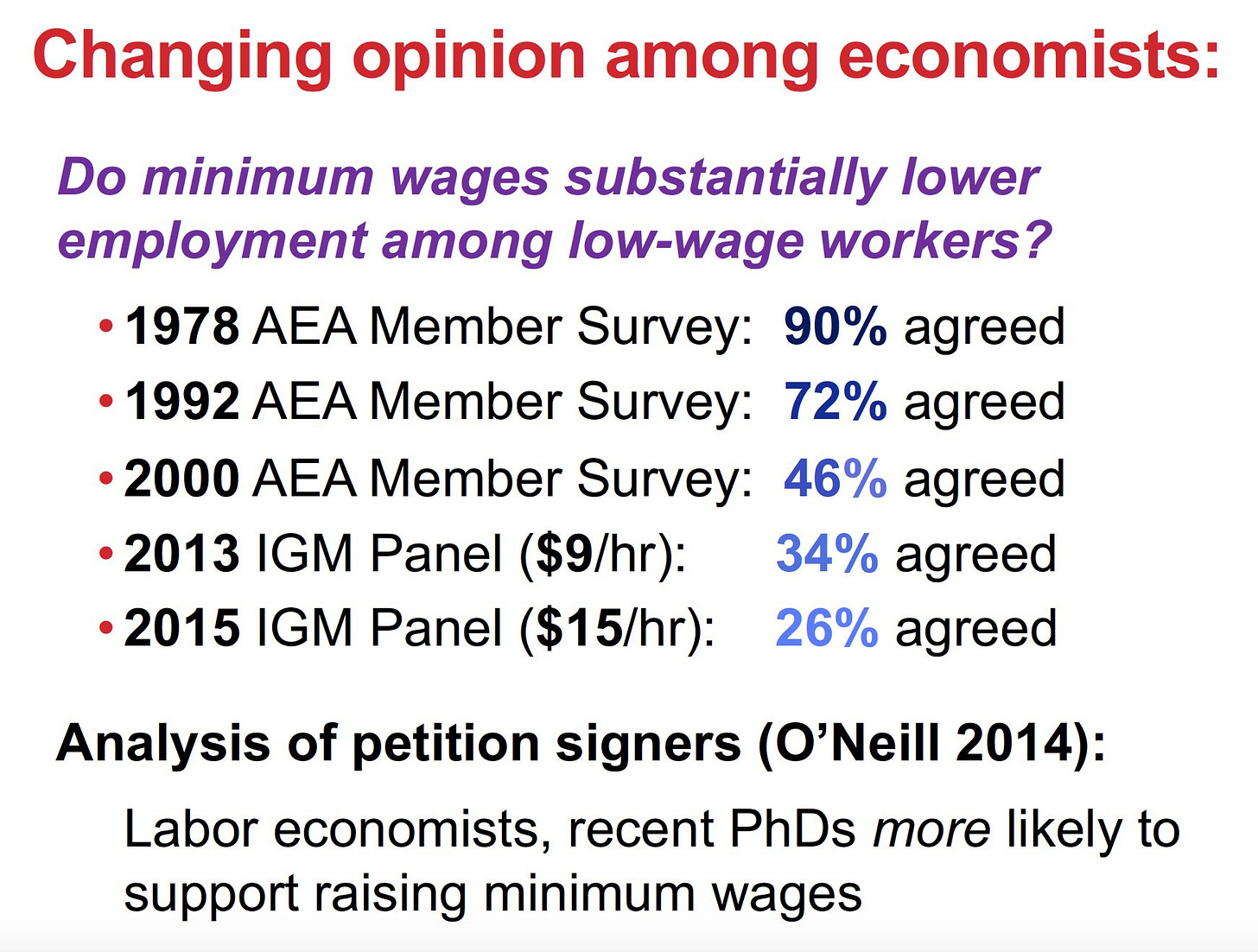

Over this time period, economists changed their beliefs about the minimum wage. As the chart at the top of this post shows, the percent of economists who think minimum wage is a substantial job-killer went from an overwhelming majority in the late 70s to a modest minority by the mid 2010s. That data is from an older version of a presentation by Arin Dube, an expert on minimum wage research. Here’s the slide from the most recent version:

That’s a pretty dramatic change, and you can see that it started before Card and Krueger did their famous study. So it’s not immediately clear how much of the shift was due to economists’ changing ideological views, and how much was due to the accumulating mountain of evidence.

But a mountain of evidence was accumulating.

The Evidence

At the behest of the UK government, Dube recently wrote a summary of the evidence. Instead of going through a bunch of papers like I did for immigration, I’ll keep it short here and just quote Dube. He writes:

In the US, a large body of high-quality research has investigated the impact of minimum wages on employment. Overall, this body of evidence points to a relatively modest overall impact on low wage employment…Across US states, the best evidence suggests that the employment effects are small up to around 59% of the median wage…Research conducted for this report also finds that in the 7 US states with the highest minimum wage, where the minimum is binding for around 17% of the workforce, employment effects have been similarly modest. Not all US studies suggest small employment effects, and there are notable counter examples. However, the weight of the evidence suggests the employment effects are modest.

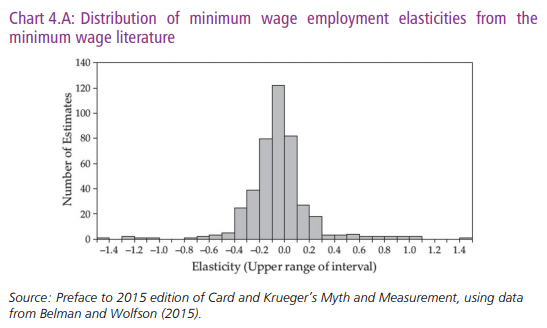

And here’s a graph aggregating a bunch of studies’ results. A positive value here means that minimum wage was found to increase employment, while a negative value means it was found to kill jobs:

Note that while most studies conclude that the effects of minimum wage are small, many actually conclude that higher minimum wages create jobs.

In fact, there’s a pretty clear and simple reason why this could happen. It’s called “monopsony power”. So let’s take a moment and review the basic Econ 101 theory of the minimum wage.

The Theory

If the market for low-wage labor is competitive — if there are a bunch of companies all scrambling to compete to hire workers, and a bunch of workers all scrambling to compete for jobs — then you can represent the labor market with a good ol’ supply-and-demand graph. In that competitive world, a minimum wage drives a wedge between employers and employees, by forcing companies to pay more than the market rate. Theoretically, that would cause unemployment. When people say minimum wage kills jobs, this is the theory they typically have in mind.

OK, but suppose the labor market ISN’T competitive. Suppose some employers are big and powerful, or they somehow cooperate to keep wages down, or simply that it’s really hard to switch employers. Then the theory changes a lot. In the extreme case — a “company town” with only one employer — the market outcome is whatever The Company wants it to be (technically, where The Company’s marginal cost equals its marginal revenue). It has nothing to do with supply and demand! And of course, The Company is going to hold wages artificially low, which kills jobs because some people just can’t afford to work for wages that low.

In that case, minimum wage can actually create jobs. It forces The Company to raise wages, which allows more people to work. It looks like this.

This is called a monopsony model. “Monopsony” means “single buyer”, which refers to the big and powerful Company. As you can see in the graph, minimum wage moves the economy closer to full employment — it creates jobs.

Now, in the real world, you almost never have an actual monopsony. But what you often do have is something in between the first graph and the second graph. Employers don’t have complete market power, but they do have some market power. And thus, it’s possible for minimum wage to create jobs, as long as the minimum wage isn’t set too high.

That could explain why some studies find positive employment effects from minimum wage. Those could just be cases where companies’ market power was strong, and minimum wage wasn’t too extreme. And it also could explain why most minimum wage studies only find very small employment effects in either direction.

In other words, the question “Does minimum wage kill jobs?” doesn’t have a definitive, universal answer. It depends on how high the minimum wage is. It depends on how high prevailing wages are. It depends on the local labor market, and how powerful local employers are. And it probably depends on other things too, such as whether we’re in a recession.

So incoming President Joe Biden is proposing a $15 federal minimum wage. Would this kill jobs, or create jobs? Is a national one-size-fits-all policy safe, or would it screw over places where wages are naturally lower?

$15 Federal Minimum Wage

So, Dube’s literature review above suggests that in general, minimum wages aren’t harmful if they’re below about 60% of the median wage. The median weekly earnings of U.S. workers currently stands at around $994, so assuming a 40-hour workweek that’s about $24.85/hour. 60% of that is about $14.91, meaning that $15 is right around the maximum safe level. But because the economy will recover from COVID-19 and wages will rise, and because Biden’s $15 minimum wage would undoubtedly be phased in over time, $15 will probably be under the national “safe” level by the time the law goes into effect. And thanks to inflation, it will be further and further below the “safe” level every year (we really should index minimum wage to inflation, but that’s another story).

But that’s at the national level. What about at the local level? In big cities where wages (and living costs) are naturally higher, $15 won’t be any problem at all. But in small towns in Kansas, where wages (and living costs) are naturally a lot lower, a federally mandated $15 wage could be a big problem.

Fortunately, there’s reason to think that small towns won’t be so screwed by a too-high minimum wage. The reason is that these small towns also tend to have fewer employers, and therefore more monopsony power. And as we saw above, more monopsony power means that minimum wage is less dangerous, and can even raise employment sometimes.

A recent study by Azar et al. confirms this simple theoretical intuition. They find that in markets with fewer employers — where you’d expect employers’ market power to be stronger — minimum wage has a more benign or beneficial effect on jobs:

We find that more concentrated labor markets…experience significantly more positive employment effects from the minimum wage. While increases in the minimum wage are found to significantly decrease employment of workers in low concentration markets, minimum wage-induced employment changes become less negative as labor concentration increases, and are even estimated to be positive in the most highly concentrated markets.

This implies that in smaller towns where wages are naturally low, the danger of minimum wage is reduced because employers are more powerful to start with. And in bigger cities where there are lots of employers and labor markets are more competitive, the danger of minimum wage is reduced because wages are naturally high.

In other words, a $15 federal minimum wage just might be pretty safe after all.

Of course, I expect Biden’s policy — if it passes — to include a number of safeguards. It’ll probably be phased in over a number of years, like city-level $15 minimum wages typically are. There will probably be some partial exemptions for small businesses, startups, etc. There should be a policy allowing the government to reduce the minimum wage during a recession. And despite the mitigating factor of monopsony power, there may be some kind of policy that allows towns to get partial exemptions from the federal minimum wage if their prevailing wages are low enough, just to be on the safe side. (Biden’s plan does index future minimum wage increases to median wage growth, so eventually the policy would give lower-cost areas more of a break.)

But anyway, the overarching point here is that minimum wage is a lot safer than economists used to think. And we have a pretty good idea why this is true. And economists have really changed their minds on the matter.

When the evidence is clear, true scientists follow the evidence.

I don't understand why nobody ever even tries to just say "every county's minimum wage will be set each January 1st to 50% or 60% of that county's most-recent median-wage, based on whatever numbers from BEA or the Census seem most reliable."

Thanks for this. I'm very interested in whether or not min wage laws are good. I'm glad that you went into regional differences because a national min generally seemed like a bad idea to me and I would wonder if it could be tied to regional wage levels. But even with the monopsony scenario, is the assumption that if an employer has market power then they WILL be artificially keeping wages low and can afford more? I'm not trying to say that I think employers are good and will always want to pay fair wages but it seems like the argument perhaps assumes that employers will be unfair.

Also, how would you compare min wage laws to letting the market wages go but then using more gov't assistance like EITC, UBI, or something else.

Thanks again!