Who's afraid of the Huawei Mate 60 Pro?

Export controls were never going to make China's semiconductor industry vanish.

Almost a year ago, the Biden administration launched a sweeping new regime of export controls aimed at China’s semiconductor industry. These included various restrictions on sales of chips and chipmaking equipment, as well as restrictions on Americans’ ability to work for Chinese chip companies. The new rules, which I likened to a declaration of economic war, caused a fair amount of alarm and chaos throughout the Chinese chip industry.

Fast forward 11 months, and China’s boosters are declaring victory over the chip controls. A new phone made by Huawei, the company that was the #1 target of U.S. restrictions, contains a Chinese-made processor called the Kirin 9000S that’s more advanced than anything the country has yet produced. The phone, the Huawei Mate 60 Pro, has wireless speeds as fast as Apple’s iPhone, though its full capabilities aren’t yet known.

Many in China are hailing the phone, and especially the processor inside it, as a victory of indigenous innovation over U.S. export controls. Meanwhile, in the U.S. media, many are now questioning whether Biden’s policy has failed. Bloomberg’s Vlad Savov and Debby Wu write:

Huawei’s Mate 60 Pro is powered by a new Kirin 9000s chip that was fabricated in China by Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp., according to a teardown of the handset that TechInsights conducted for Bloomberg News. The processor is the first to utilize SMIC’s most advanced 7nm technology and suggests the Chinese government is making some headway in attempts to build a domestic chip ecosystem…Much remains unknown about SMIC and Huawei’s progress, including whether they can make chips in volume or at reasonable cost. But the Mate 60 silicon raises questions about the efficacy of a US-led global campaign to prevent China’s access to cutting-edge technology, driven by fears it could be used to boost Chinese military capabilities…Now China has demonstrated it can produce at least limited quantities of chips five years behind the cutting-edge, inching closer to its objective of self-sufficiency in the critical area of semiconductors.

In fact, the rush to declare that the Kirin 9000S spells doom for the export control regime has produced some odd bedfellows — hawkish types think it shows the export controls need to be dramatically tightened, while supporters of “engagement” argue that the new chip proves the controls are futile, but both agree that the Kirin 9000S is a heavy blow to the Biden administration’s approach. The most dramatic statement of confidence in China’s indigenous chip industry that I’ve seen so far comes from the research firm SemiAnalysis, which predicts that Chinese chipmaker SMIC will be able to work around all of the equipment limitations that have so far been proposed.

Many long-time observers of the chip wars are urging caution, however. Ben Thompson of Stratechery argues that it was always likely that SMIC would be able to get to 7nm — the level of precision represented by the Kirin 9000S — using the chipmaking tools it already had, but that export controls will make it a lot harder to get down to 5nm. Basically, the U.S. has taken great care not to let China get the cutting-edge Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography (EUV) machines, but China already has plenty of older Deep Ultraviolet Lithography (DUV) machines (and ASML is still selling them some, because the export controls haven’t even fully kicked in yet!).

EUV lets you carve 7nm chips in one easy zap, but DUV machines can still make 7nm chips, it just takes several zaps. China analyst Liqian Ren calls this “a small breakthrough using software to solve the bottleneck of hardware” Bloomberg’s Tim Culpan explains:

Instead of exposing a slice of silicon to light just once in order to mark out the circuit design, this step is done many times. SMIC, like TSMC before it, can achieve 7nm by running this lithography step four times or more…

[Trying to prevent China from making 7nm chips by denying them EUV machines is] like banning jet engines capable of reaching 100 knots, without recognizing that an aircraft manufacturer could just add four engines instead of one in order to provide greater thrust and higher speeds. Sure, four engines may be overkill, inefficient and expensive, but when the ends justify the means a sanctioned actor will get innovative.

In other words, even without the best machines, Chinese companies can make some pretty precise chips. It’s just more expensive to do so, because of higher defect rates and the need to use more machines to make the same amount of chips. But when has cost ever deterred China from making whatever they wanted? China’s great economic strength is the massive mobilization of resources, and if they want to make 7nm chips, they’re not going to let a little inefficiency get in the way. Remember, Huawei’s big success in the telecom world came from Chinese government subsidies that allowed them to undersell Western competitors by enormous amounts. There’s no reason they can’t use that approach for 7nm chips, and eventually maybe even 5nm chips.

But this doesn’t mean the U.S. should give up on the export control regime.

First of all, the main argument that opponents of the controls are throwing around — that export restrictions will just push China to innovate faster — makes little sense. It’s hilariously unrealistic to think that if the Biden administration dropped all export controls tomorrow, Chinese companies would just go right back to buying their chips from Qualcomm, cheerfully relying on U.S. technology and scrapping their plans for innovation. The cat is entirely out of the bag here; the Chinese government is dead set on indigenous semiconductor capabilities, and it will continue using all of the formidable tools at its disposal to push indigenous chipmaking innovation as hard as it can. All that dropping the controls would do at this point is to accelerate those efforts.

And if export controls really did accelerate the pace of Chinese innovation, it’s unlikely that China’s government would be howling about them so strongly and consistently. Just before the recent G-20 summit, China suggested trading action on climate change for an end to export controls. If those controls were really good for Chinese technology, as some claim, why would China be trying to get them dropped? It makes no sense.

In reality, what the U.S. needs to do is to A) temper our expectations for what export controls will accomplish, and B) constantly tighten the controls based on our observations of what China is doing to circumvent them.

As Chris Miller writes in his book Chip War, export controls on the USSR were highly effective in denying the Soviets a chip industry. But even then, the Soviets were able to copy all of the U.S.’ most advanced chips. They just couldn’t make them reliably in large batches, so their ability to get their hands on chips for precision weaponry was curtailed.

Similarly, no one should have expected U.S. export controls to make China’s chipmaking acumen suddenly vanish into thin air. China has a ton of smart engineers — far more than the USSR ever had, given its much larger population. What the Cold War export controls showed was that a foreign country’s technological capabilities can’t be halted, but they can be slowed down a bit. If Huawei and SMIC always take longer to get to the next generation of chips than TSMC, Samsung, Intel, etc., China’s products will be slightly inferior to those of their free-world rivals. That will cause them to lose market share, which will deprive their companies of revenue and force them to use more subsidies to keep their electronics industry competitive.

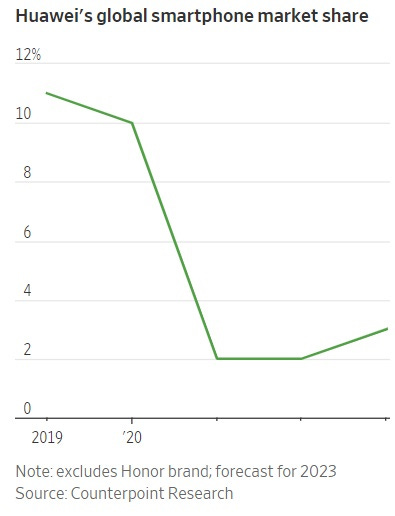

Jacky Wong of the Wall Street Journal points out that the Kirin 9000S is still generations behind cutting-edge TSMC chips. He also notes that export controls on Huawei tanked its share of the global smartphone market:

In other words, expensive-to-make chips with slightly trailing performance will slowly deprive Chinese companies of market share, and thus of the market feedback necessary to help push Chinese chip innovation in the right direction. The Chinese state can lob effectively infinite amounts of money at Huawei and SMIC and other national champions, but its track record is very poor in terms of getting bang for its buck — or even any bang at all — from semiconductor subsidies.

And the greatest irony is that China’s government itself may help speed along this process. Confident of its ability to produce high-quality indigenous phones, China is starting to ban iPhones in some of its government agencies. Those hard bans will likely be accompanied by softer encouragement throughout Chinese companies and society to switch from Apple to domestic brands. That will give a sales boost to companies like Huawei, but it will slowly silence the feedback that Chinese companies receive from competing in cutthroat global markets. Voluntary Chinese isolation from the global advanced tech ecosystem will encourage sluggish innovation and more wasteful use of resources — a problem sometimes called “Galapagos syndrome”.

What effect all this will have on China’s military capabilities isn’t clear, because that depends a lot on the pace of military innovation. It might be that old chips are fine, and China can just overwhelm the forces of developed democracies with sheer mass of missiles and drones. Or it might be that new AI algorithms that allow the creation of highly effective drone swarms might need to run on bleeding-edge chips, in which case China could be at a qualitative disadvantage in a fight. We just don’t know for sure; the argument that China’s military will be hampered by a weaker chipmaking industry is probabilistic, not a law of the Universe. But it’s still one thing that might help put a check on Chinese expansionism in the 2020s and even the 2030s, and every little thing counts.

That all having been said, the Kirin 9000 S also undoubtedly shows holes in the U.S. export control regime. The reaction of ASML’s CEO Peter Wennink to the release of the Mate 60 Pro — a repetition of the old argument that export controls are actually good for Chinese innovation — suggests that the Dutch company yearns for the chance to grub a few more euros of short-term earnings by selling its crown jewels to China. It’s not an eager partner in the export control regime — which is unsurprising, given that it’s just a profit-seeking enterprise located in a small country halfway around the world from China. It will try to sell as much to China as it can get away with.

In fact, the bloggers at SemiAnalysis list several ways that the existing export control rules still allow China to get its hands on DUV machines like the ones that made the Kirin 9000S. They list a number of additional tools and materials that could be restricted in order to make the export controls regime more effective. To me, this shows that loopholes need to be tightened up on an ongoing basis; export controls should be seen as an exploratory, evolving process, instead of a one-and-done silver bullet. In that sense, China’s new chip and phone are potentially a good thing for export controls, because they teach U.S. policymakers how to make those rules more effective at their stated purpose. China learns, but the U.S. learns too.

Update: In the comments, Stan makes what I think is an important point: It’s likely that this chip and phone were likely in the pipeline before the Biden administration’s expanded export controls even went into effect (but when EUV machines had already been restricted):

This means that Biden’s new controls from late 2022 are more of a reaction to the inadequacy of the initial EUV-only restrictions that started under Trump — which reinforces the notion that export controls are an evolving process that has to be constantly observed and adjusted. Of course, if the folks at SemiAnalysis are correct the 2022 controls are still inadequate and need to be supplemented by a raft of new measures. I think that kind of constant course-correction should be our initial expectation going into something like this.

Update: Here’s a good interview with Dylan Patel at ChinaTalk, in which he explains the details of how China evades U.S. export controls. There’s lots of room to tighten up the controls.

No one seems to have commented on the time it takes to get from chip technology to chip to chip in a new product.

This is much more than 12 months so a new phone with a new chip today has nothing to do with restrictions implemented less than a year ago.

Despite some reports out there, this isn't domestication of chip making in China at all--they are still using old imported lithography machines, just in a novel way to juice out chips a few nanometers below what they are intended to make. The machines themselves are still from the Netherlands with German mirrors and full of American IP with complexity beyond the limit of human comprehension. What China is finding out now is the limits to their old equipment. It doesn't reflect a failure in sanctions regime at all, and I'd guess that their capacity to keep up with the West in chips will diverge over time. Taiwan was making 7nm chips five years ago.