Where China is beating the world

On high-speed rail, EVs, and solar, China is doing truly amazing things.

Interviewing Dan Wang has made me want to write more about China’s economy, so here’s one of a short series of posts.

Over the past two years I’ve written a lot of criticism of China’s economic policies. There were basically two reasons for that: First, China really did make a bunch of policy blunders during that time, and second, there was a narrative of Chinese economic infallibility in the late 2010s that needed correcting. Now I think that correction has largely been accomplished, and I see the possibility of an opposite narrative of Chinese economic incompetence taking hold. That would also be a mistake. The truth is that China has some serious weaknesses but also some amazing strengths, and we need to pay attention to both.

In fact, I think they’re connected. In his book China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know (which is excellent and which I heavily recommend), Arthur Kroeber offers a grand unified theory of the country’s economy — that it’s good at rapidly and effectively mobilizing lots of resources, but bad at using those resources in an optimally efficient way. So in the case of say, building too many apartments, or failed Belt and Road projects, or wasteful corporate subsidies, the lack of efficiency can really bite. But if we’re talking about building the world’s biggest high-speed rail system, or creating a world-beating car industry from scratch, or building massive amounts of green energy, then China’s resource-mobilizing approach can accomplish things on a scale no other country has ever accomplished before.

High-speed rail

Remember a few years ago, when a bunch of people were sharing this map of a hypothetical U.S. high speed rail system?

Of course, the map and others like it were pure fantasy; in 15 years, California’s much-ballyhooed high speed rail project has managed to almost complete one small segment out in the middle of nowhere. That’s the extent of the U.S.’ high speed rail prowess.

But in China, they actually built the map!

In the last 15 years, China, starting from scratch, built a high-speed rail network almost as twice as long as all other high-speed rail networks in the world, combined. I’m not exaggerating; you can look these numbers up on Wikipedia. As of last year, China had 42,000 km of high-speed railways in operation, with another 28,000 km planned. That’s compared to just 2,727 km in Japan, with its famous shinkansen.

And it’s not just the size of this network that’s incredible; it’s the speed. Here’s a series of pictures showing all the high-speed lines China built in the decade between 2008 and 2017:

The speed of Chinese rail construction has to be seen to be believed. Here’s a video showing work on a train station that was built in nine hours.

And China built the system very cheaply — 40% cheaper than Europe, on a per-kilometer basis.

How did China manage this? Well, for one thing, it didn’t have to invent the technologies of high-speed rail as it went along, like Japan and Europe did; instead, China got Japanese and European companies to hand over their technology in exchange for the unspoken (and ultimately unfulfilled) promise of big Chinese contracts.

That was far from the only factor, though. As the World Bank explains, China is the world’s manufacturing center, and thus has all the suppliers for a high-speed rail network in-country. Not only does that allow for quicker coordination among contractors and suppliers, but because both the contractors and the suppliers have basically guaranteed demand from the Chinese government, they can massively ramp up production of everything that’s needed to build a train, instead of having to increase and decrease their capacity in response to intermittent demand as in other countries. The in-country network of suppliers also allows the Chinese government to standardize everything instead of having to work with a patchwork of international standards.

Other factors include the fact that China’s government system allows it to grab land for trains more cheaply and quickly than in other countries, a massive glut of steel and other materials, and a very rapid permitting system (construction typically begins less than a year after the first feasibility study).

Some might assume that this rapid construction would compromise safety — after all, if you build all your trains in a highly standardized fashion, special local factors might eventually cause problems in some of the lines. But there’s little sign of safety problems so far; China did have one big high-speed train crash in 2011, since then the safety record has been excellent. Of course, problems might crop up as the lines age, so we’ll see.

China’s high-speed rail network is inarguably a monumental feat — one of the true wonders of the modern world. Less clear is whether it makes sense from an economic standpoint. China’s HSR network has some ferocious critics, such as the economist Zhao Jian of Beijing Jiaotong University, who has alleged that the rail system doesn’t make enough money to cover the cost of its construction, operation, and financing. The World Bank’s analysis suggests that so far, many of the faster lines are profitable, but the slower lines in the system don’t yet make enough money to cover the interest on the debt that was used to finance them:

That would be consistent with the experience of Japan and France, where high-speed railways can rarely turn a profit off of ticket revenue alone.

Defenders of the system, like the investor Glenn Luk, counter that demand for the system will increase over time. The World Bank finds that the unprofitability of China’s HSR system is due to very low ticket prices; in the future, as people get used to using the high-speed rail system, the trains might be able to hike ticket prices while keeping ridership high.

Luk also argues that high speed rail will create positive externalities through agglomeration effects that will make even money-losing lines economically advantageous. Personally, I’m skeptical that these effects are large. A 2018 study by Charnoz et al. found that France’s HSR network raised corporate profits by about 2%, by making business travel easier — not nothing, but it’s not enough to really change the economic calculus of these trains. Theoretically, true agglomeration requires the movement of both goods and people, and HSR really only carries people. And if HSR ultimately displaces freight trains, as Jian alleges it eventually will, it could end up having the opposite effect on agglomeration (so far, freight trains have just taken over some of the slower train lines displaced by the HSR). Still, it’s possible that HSR feeds the growth of other transportation networks, allowing cities to become effectively denser, and that this benefit is large and unmeasured.

So I’d say the jury is still out on whether China’s massive high-speed rail will ultimately be worth the cost overall, or whether only some of the lines are worth it. But one thing is for certain — the creation of the network is one of the single greatest feats of resource mobilization and civil engineering of all time.

Electric vehicles

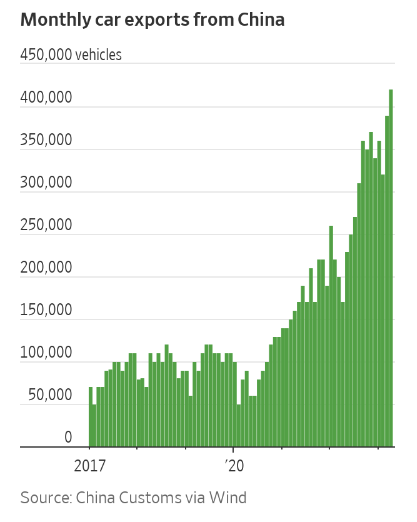

China is the world’s manufacturing superpower, but until recently there were three big things that Chinese companies couldn’t seem to make as well as Europe, Japan, Korea, or the U.S. Those things were computer chips, wide-body aircraft, and cars. Well, time to scratch the third item off the list. For decades China struggled in vain to break into the global car market. But in the last two years, that has changed in a big way. Since 2020, Chinese car exports have more than quadrupled:

China is now the world’s biggest auto exporter, having rapidly overtaken Germany and Japan.

A minor factor here is the Russia sanctions, which have caused Russia to start buying its cars from China. But the main reason is the massive shift in the global auto industry, from internal combustion cars to electrics.

Internal combustion engines are a complicated technology, with lots of tacit knowledge distributed across the workforces of big old companies like Volkswagen, Toyota, and GM. That’s the kind of technology that it’s notoriously difficult for Chinese companies to either copy or steal. Also, the global car market was crowded with established brands with established dealer networks, mindshare, etc.

Then came the big shift to EVs. Electric motors are a much simpler and more standardized technology than internal combustion engines. And because the technology was new, Chinese companies weren’t at a disadvantage versus foreign incumbents in terms of building up tacit knowledge about how to build EVs cheaply and well.

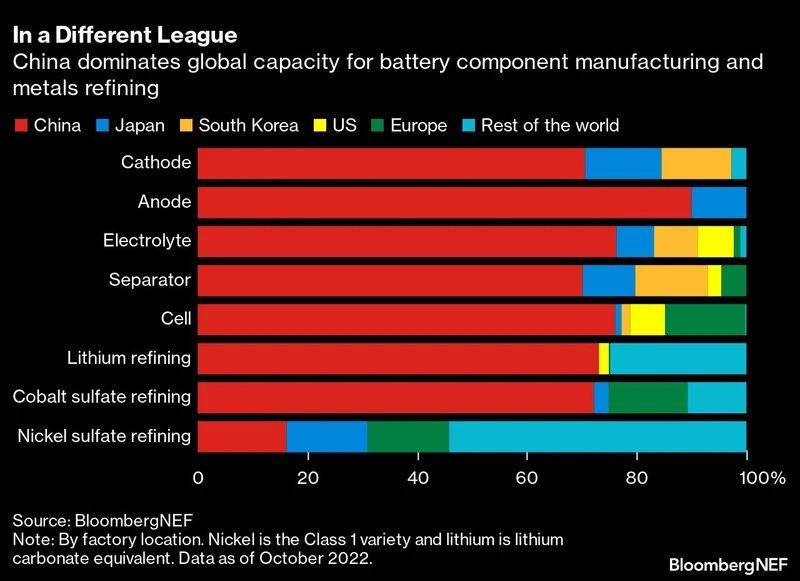

And China also owns the most important upstream inputs to EVs — most importantly, batteries, and the materials and components used to make batteries.

That means if you’re an automaker located in China, all the batteries are right there; it’s easy to secure as much supply as you want, and it’s quick and cheap to transport the batteries to the factory.

But there’s one more big factor that’s allowing China’s EV industry to leapfrog the world: scale. Because legacy automakers mostly make internal combustion cars, they can’t easily scale their EV businesses. China’s EV companies, starting from scratch, can pour all of their resources — their engineers, their land, their financial capital — into making EVs, which allows them to make EVs much more cheaply. And because fewer Chinese people had cars of any kind to start with, the domestic Chinese market was able to provide Chinese EV makers with a huge and almost guaranteed source of demand that allowed them to scale up quickly, reducing costs.

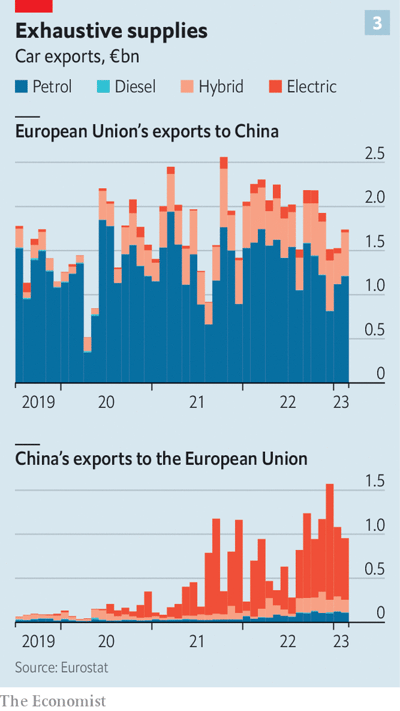

Thus it’s no surprise that Europe, which is working hard to switch its car fleet to EVs, has recently become a massive importer of automobiles from China. Soon that may cause one of the EU’s main sources of net exports to China to flip into a trade deficit:

This looks like a huge success for Chinese industrial policy, which has struggled in other industries, but which successfully used dominance of the battery supply chain and generous subsidies to position China for global dominance in autos. (Interestingly, the auto industry is generally believed to be the biggest success of Japan’s industrial policy back in the 70s and 80s, so it may be that autos are just one industry that’s very amenable to government support.)

Now, a couple caveats here. First, China’s massive expansion of automaking capacity has left many of its car companies unprofitable. The winners, like BYD, are now profitable, but their margins are still lower than traditional car companies. So I’d expect to see some consolidation and moderation of the industry’s growth.

Also, many of the EVs made in China are still made by foreign brands. Tesla has put a lot of its factories in China, and most of the EVs that Europe imports from China are either from Tesla or are European brands. China’s own domestic EV brands like BYD are still mostly competing by underselling the competition in developing markets; you don’t see many people in rich countries driving BYD cars. That could change, of course, but for now Chinese companies aren’t reaping all of the profits of the manufacturing they’re doing.

Still, China’s rapid rise to dominance in auto exports — which, unless the legacy automakers and rich countries can get their acts together very quickly, will turn into dominance of car exports, period — is a marvel to behold. Once again, China’s ability to marshal and deploy vast resources has created something out of nothing almost overnight. Ultimately the whole world will benefit from the shift to EVs, but for now, it’s raking in huge export earnings for China and providing tons of jobs to a country that needs them very badly.

Solar power

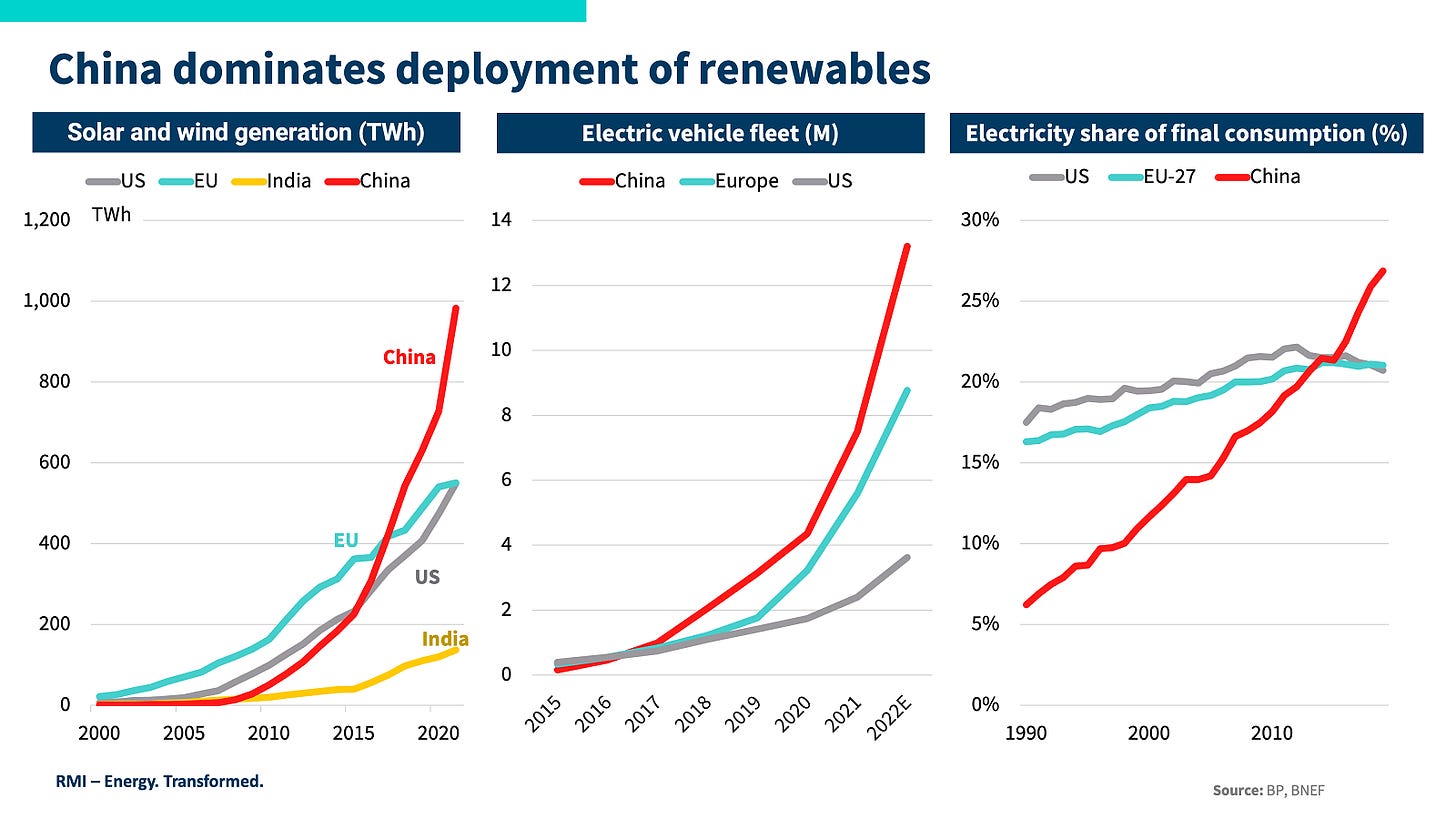

China is the world’s biggest contributor to climate change by far, largely due to it’s vast coal industry, which is still expanding. But China is also the biggest contributor to the solution to climate change — or at least, its technological component. By massively scaling up the deployment of solar and wind power, China has helped to drive down the cost of these technologies, via the magic of learning curves. That will ultimately make solar and wind cheaper than coal and gas for countries all across the world, which will make it economically worth their while to use renewables instead of fossil fuels even without taking climate impacts into account. Ultimately, this will be crucial in holding back climate change.

The sheer scale of China’s deployment of renewables is staggering. Over the past few years, China has zoomed ahead of both the EU and the U.S. in solar and wind production:

And it’s still accelerating. 2023 solar installations are far outpacing previous years:

China is adding more renewable energy than the U.S., EU, and India combined, even though its total GDP is only about half as large. Much of this advantage, of course, is due to the fact that most of the world’s solar panels are produced in China.

Once again, this is the outcome of China’s skill at massive deployment of resources. The transition to green energy A) benefits enormously from scaling effects, and B) needs to happen quickly to minimize climate change. Maximizing short-term economic efficiency was just never going to make this happen; China thus did what the U.S. and Europe could not. And it ultimately paid off, not just environmentally but financially — China’s solar panel makers were unprofitable and subsidized a decade ago, but now make healthy profits (well, some of them do, anyway).

In high-speed rail, electric vehicles, and solar power, China has shown the amazing power of large-scale resource mobilization. The result isn’t always profitable or efficient in the short term (though sometimes it is). It isn’t always the right approach. But it can and does accomplish some great things — technological and industrial miracles that no other country on Earth can come close to. It’s an approach the developed democracies should pay attention to and learn from — the kind of thing we used to do in the early 20th century, and then abandoned later in terms of quarterly earnings, efficiency, and comfortable stasis.

Not mentioned in the article, especially for the US audience, is that high-speed rail is a much more pleasant way to travel than flying. You can arrive at the high-speed rail station a half-hour before departure (usually via modern, fast, reliable, clean, safe subway system), much simpler security measures, only need your ID for boarding, start up so smooth you hardly know you're moving, smooth ride, comfortable seats, quiet, electrical power at the seat, ability to get up and walk around, no turbulence, wireless connectivity, cheaper (for "economy", and the next tier up is about the same cost as flying), no weather delays. For longer distances flying is faster and common. But for short and intermediate distances, the high-speed rail is the preferred way to travel.

I think it was Freddie DeBoer that recently wrote about how progressive environmental regulation was making it impossible to actually build anything. Noah here has talked about now nonprofits are sopping up large percentages of the money we allocate to new projects and ideas.

In practice, this means that in the time America builds 40 miles of high speed rail track in Nowherev-ille, CA, the Chinese build out hundreds of miles of functional track connecting most of their major cities. (I live CA so am very familiar with the CA High Speed Rail boondoggle.) I don't care what your politics are, whether you're a Bernie-bros, a rabid libertarian, a Amari integralist, a BLM cultural Marxist, or an Amish escapist... everyone must acknowledge that this is a problem.

China has a "screw private property, living wages, human rights, safety, and environmental concerns, and just build the darn thing" approach. We have a "study it to death but for God's sake don't actually do anything" approach. Neither approach is efficient. But if your goal is to create things that might improve quality of life, the former is at least effective.