What is an American?

We are bound together by shared culture, not by online memes about "heritage".

“You can go to live in France, but you cannot become a Frenchman. You can go to live in Germany or Turkey or Japan, but you cannot become a German, a Turk, or a Japanese. But anyone, from any corner of the Earth, can come to live in America and become an American.” — Ronald Reagan

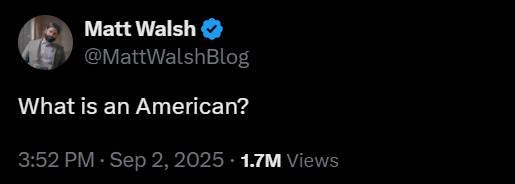

There’s a meme going around on right-wing social media, where right-wing influencers ask “What is an American?”. Some don’t give answers, and simply assume that people who read the question will start thinking along the lines they want:

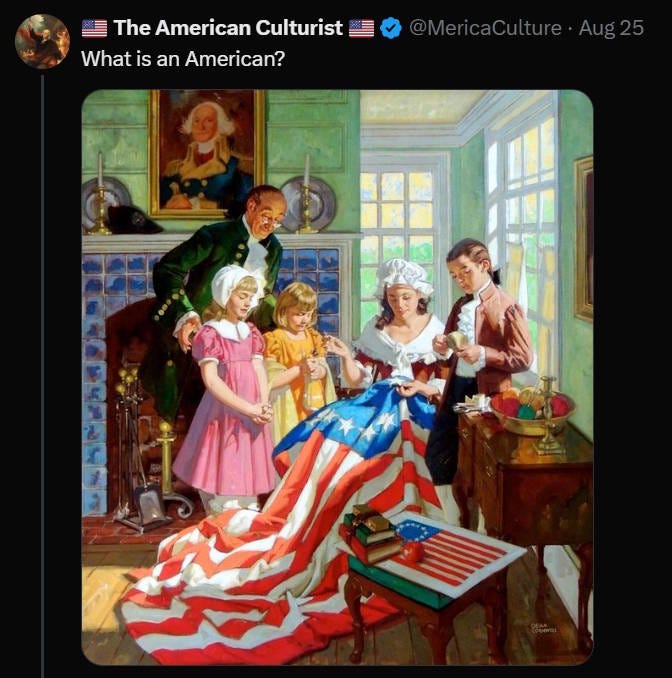

Others merely prompt the reader with evocative images:

But some do give answers, and their answers give a glimpse into how the political right is thinking in America nowadays:

What’s interesting on this chart is that the author — who may or may not himself be American, but who is certainly doing a good job of riling Americans up on social media — doesn’t try to establish a hard and fast cutoff, but instead defines a system of grades, where the longer your ancestors were in the country, the more points you get.

This kind of thing is natural in a polyglot country of immigrants like America. In every country you’ll find some form of restrictive nationalism — the idea that no matter what the citizenship laws say, only certain groups of people are truly members of the nation. But in most countries, there’s some kind of hard cutoff you can use — usually, membership in a specific ethnic group or religion. But America is so diverse that any attempt to draw a hard, bright line around which groups are “real Americans” is probably going to fail, because the cutoff will be transparently arbitrary. And so our restrictive nationalists resort to drawing concentric circles, defining a whole spectrum of American-ness based on some combination of family history, race, ethnicity, and religion.

This idea seems to be gaining power on the right. Online, you hear the term “Heritage American” thrown around a lot. C. Jay Engel, who has done a lot to popularize the term, sees “Heritage Americans” as people who value both the racial composition and the racial hierarchy of the U.S. before World War 2:

When I say Heritage American, this is what I mean: those who are ethno-culturally tied to the ethos and spirit of the United States prior to its definitional transformation into a Propositional Nation after World War II. This therefore includes the type of people that came here during the Ellis Island generation, even if that was a significant sociopolitical mistake. We are also the product of our mistakes as a nation.

It includes the blacks of the Old South (like Booker T Washington), though it repudiates any instinct that some of them have to leverage their experience for the purposes of political guilt in our time. It also includes integrated Native Americans with the same stipulation.

It affirms however the domination and pre-eminence of the European derived peoples, their institutions, and their way of life. Heritage America is centered around the experiences and norms of Anglo-Protestants.

This is pretty vague — there’s no test you can really do to tell if someone is or isn’t a “Heritage American” under this definition. In fact, the right can’t agree at all who exactly qualifies. A blogger calling himself “Ragnar Lifthrasir” defines the idea purely in ethnic terms (though he allows for other ethnicities to attain “ally” status):

[U]nderstanding who Heritage Americans are has never been more urgent. These descendants of the Founding Americans—Protestant, English-speaking, Northwestern Europeans who built the nation from Jamestown through the 1870s—represent more than ancestry. They embody a distinct American ethnicity forged through centuries of frontier experience, constitutional development, and cultural synthesis…

[There are also] those who are not Heritage Americans but who unequivocally support Heritage America…I call these citizens, “Ally Americans”. They can be of any ethnicity or faith or immigration vintage. But they advocate for America remaining a predominantly White, Christian nation governed by the spirit and letter of America’s founding documents.

Ben Crenshaw, on the other hand, adds an ideological element to the definition (something that Engel explicitly rejected):

For most nations of the world, to be considered a true German or Italian or Chinese or South African you must be a blood descendent (and thus exhibit common genetic traits), you must live in a geographical location where those people have historically lived, and you must abide by certain customs and ways of life. While America is not a “propositional nation,” neither does she neatly align with how other peoples have historically associated. Heritage America is not reducible to “blood and soil” fearmongering, yet neither are family, kin, and the land unimportant in America’s identity.

What does it mean to be an American? Heritage America is best understood as involving seven inheritances: the English language, Christianity, self-government, Christian government, liberty, equality under the law, and relationship with the physical land.

All these people can agree that “Heritage Americans” are an important group, but none of them can agree on who exactly belongs in that group.

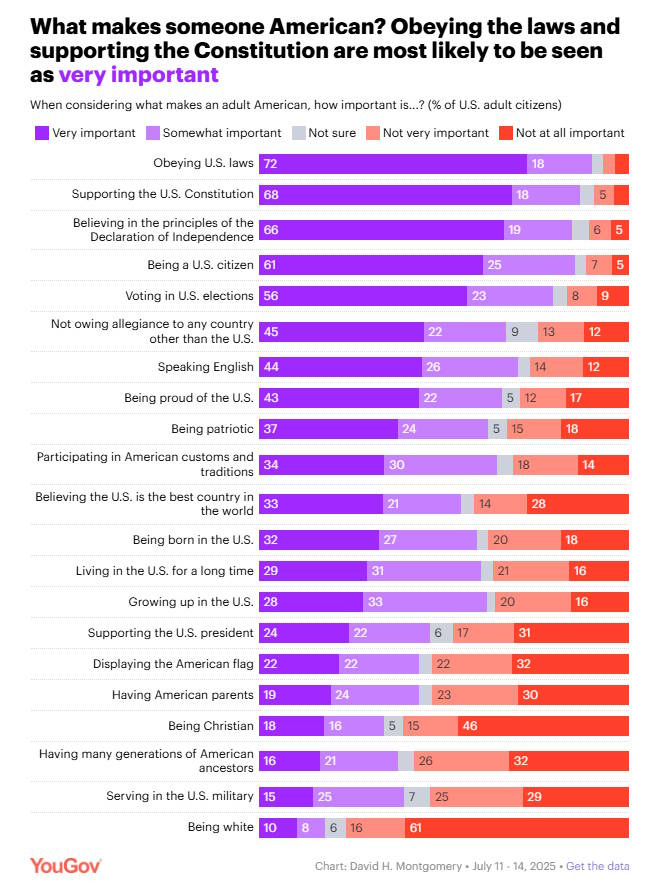

It’s important to recognize that all of these ideas are well outside of the mainstream. YouGov did a poll this summer asking Americans what makes someone an American. Most of the items at the top of the list were behaviors like obeying the law, voting, speaking English, and beliefs like supporting the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, not owing allegiance to other countries, and so on. Ethnicity, race, religion, and family history all scored at the bottom of the list:

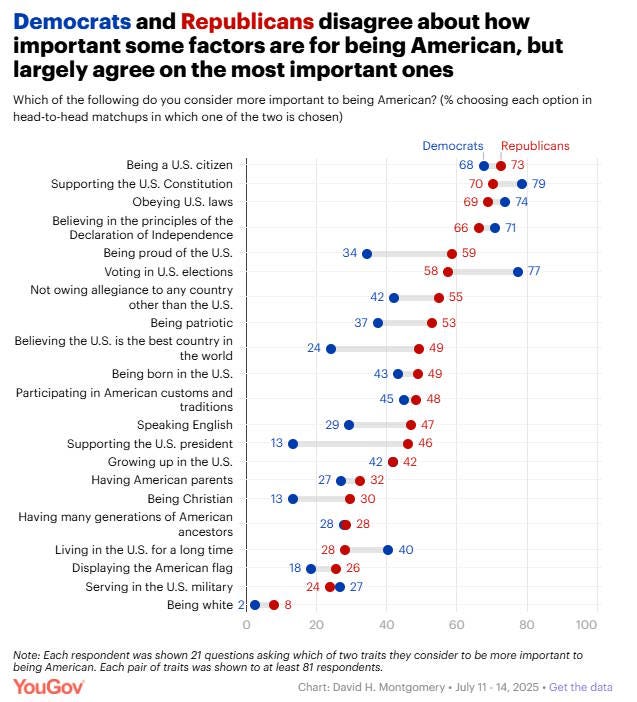

YouGov also asked a bunch of head-to-head matchups about which of these traits was more important, and the results came out basically the same. Furthermore, the partisan breakdown didn’t show particularly stark differences between Republicans and Democrats on who belongs:

It’s important to note that this poll came out after Trump’s 2024 victory, after the eruption of popular anger over uncontrolled immigration, and well after the “vibe shift” that saw America take a more conservative turn. It closely matches the results of a similar poll in 2021 by Pew, another similar poll by the VOTER Survey in 2017, and others too. Americans consistently say that race and religion are far less important to them as markers of shared nationhood than belief in American ideals and behavior consistent with that belief.

So why should we care what some online weirdos think, if they’re so out of the mainstream? The answer is that in the age of social media, it’s not necessarily mass opinion that determines policy — at least, not in the short term. Regular Americans may be tuning the “Heritage American” stuff out, but young Republican staffers are absolutely marinating in this online stuff, and they’re the future of the party. As Politico reports, savvy politicians and social media managers courting the young right-wing base are already making reference to the “Heritage Americans” term:

While the specific worldview surrounding “heritage America” may have been incubated online, it is increasingly finding its way into the policies and rhetoric of the Trump administration. In a speech at the conservative think tank the Claremont Institute in July, Vice President JD Vance urged conservatives to reject the view that America is founded exclusively on a common creed, reviving a theme from his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention last year. “America is not just an idea — we’re a particular place with a particular people and a particular set of beliefs and way of life,” said Vance…If the subtext wasn’t clear enough, he added: “That is our heritage as Americans.”

The iconography of the heritage America movement has surfaced in the Trump administration’s messaging…In early July, the Department of Homeland Security’s official account on X posted a painting of a pioneer couple cradling a baby in the back of a covered wagon, under the caption: “Remember your Homeland’s Heritage.” Later the same month, DHS followed that post up with another one featuring John Gast’s painting American Progress, captioned “A Heritage to be proud of, a Homeland worth Defending.”

And Eric Schmitt, a senator from Missouri, gave a speech at the recent National Conservativsm convention called “What is an American?”, expressing similar sentiments to what you’d hear from online rightists:

At this point, it should be clear that the fact that something is sanctioned by our government does not mean it’s good for our country. That much is obvious with various forms of legal immigration today…

We Americans are the sons and daughters of the Christian pilgrims that poured out from Europe’s shores to baptize a new world in their ancient faith…

My ancestors arrived there from Germany in the 1840s…The first settlers in my state were mostly Scots-Irish—a hard, proud, fiercely independent people, forged in the hills of Ulster and the backwoods of Appalachia, ideally suited to life on the edge of civilization. They were the ancestors—as it just so happens—of my friend and our vice president, JD Vance.

As the historian David McCullough writes, the Scots-Irish families that first settled Missouri “saw themselves as the true Americans”…For some time now, we’ve been taught to be ashamed of these things that defined us[.]

To these “national conservatives” who now control much of our government, the struggle to make Heritage Americans the country’s dominant group is paramount, taking precedence over economic concerns, and even over defense against foreign enemies. A new National Defense Strategy being considered by the Trump Administration would basically see American power withdraw from the entire world in order to focus on the struggle to deport immigrants from the U.S.:

Pentagon officials are proposing the department prioritize protecting the homeland and Western Hemisphere, a striking reversal from the military’s yearslong mandate to focus on the threat from China…A draft of the newest National Defense Strategy, which landed on Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s desk last week, places domestic and regional missions above countering adversaries such as Beijing and Moscow…[I]n many ways, the shift is already occurring. The Pentagon has activated thousands of National Guard troops to support law enforcement in Los Angeles and Washington[.]

To the “natcons”, the paramount threat to America is immigration, not any foreign adversary. JD Vance has already expressed that sentiment with regards to Europe, and there can be little doubt that he and his fellow-travelers — who at this point dominate the Trump administration, and thus the MAGA movement, the Republican Party, and thus the nation as a whole — feel the same about America.

Trump renamed the Department of Defense the Department of War, but it’s clear that the main “war” he thinks he’s fighting is against immigration:

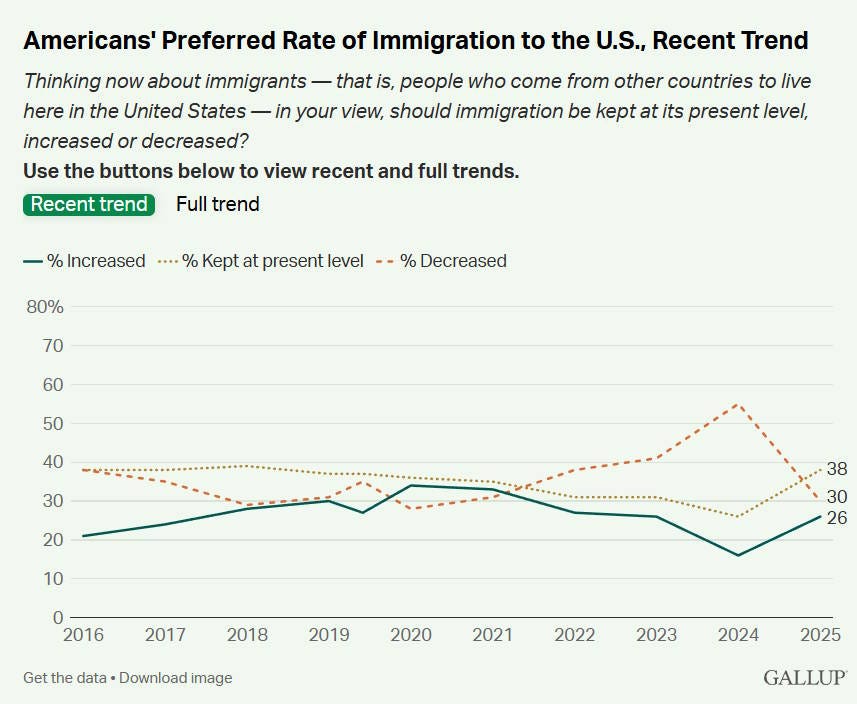

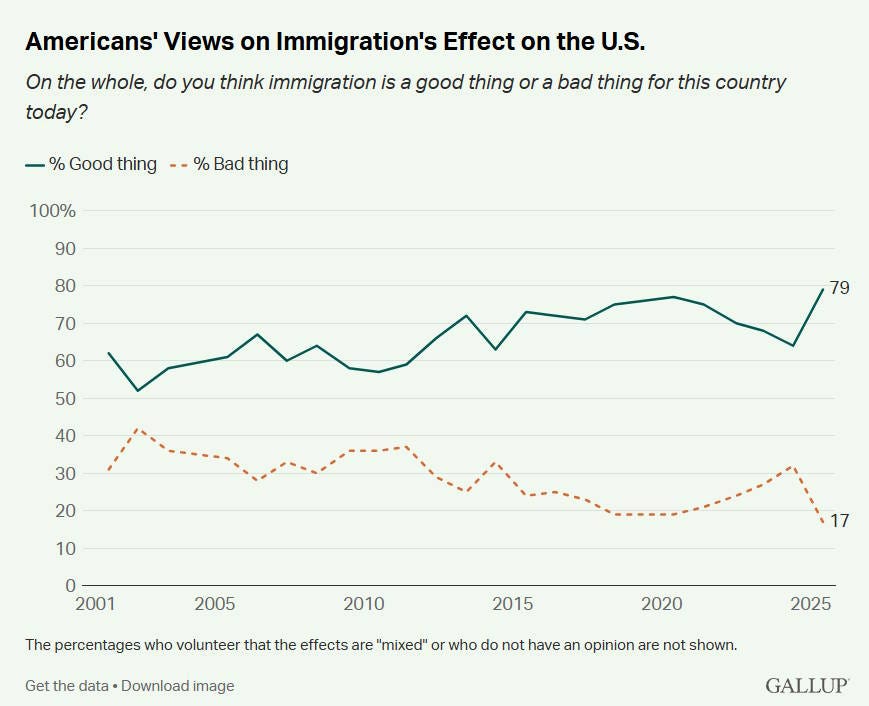

But this idea of immigration as an invasion, and deportation as a war, isn’t shared by the majority of Americans. Gallup has begun to see a major backlash against Trump’s anti-immigrant jihad. The fraction of Americans who wanted to decrease the rate of immigration soared under Biden, but has now plummeted back to where it was in Trump’s first term:

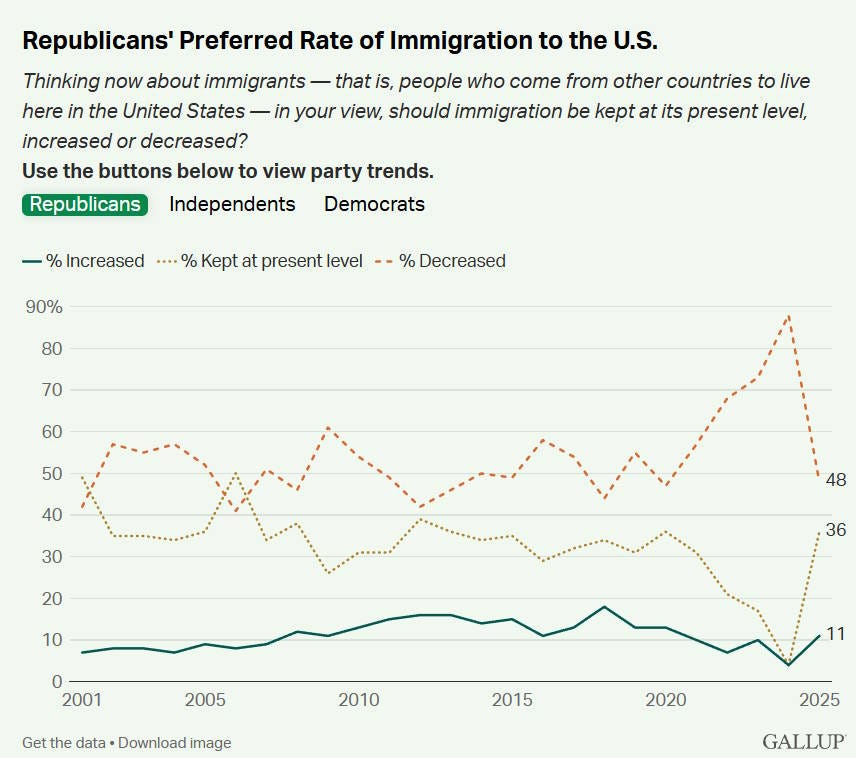

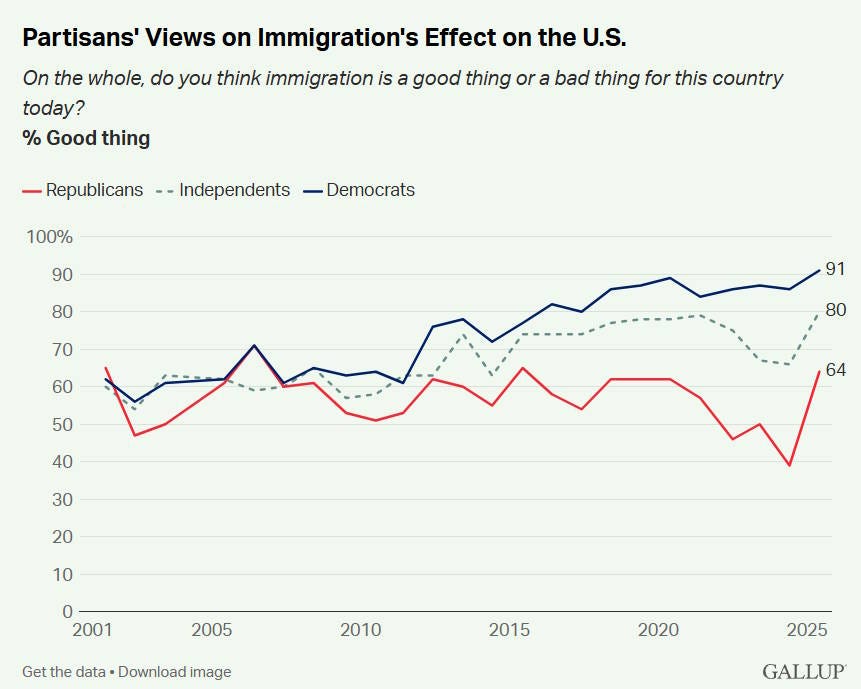

Interestingly, the shift is even sharper among Republicans:

And the percentage of Americans who say immigration benefits the nation is surging:

Again, this shift is happening more among Republicans than among Democrats:

Republicans still generally approve of Trump’s immigration policy. But this shift suggests that many Republicans are satisfied with what Trump has done so far, and don’t want to see it go much farther. They probably do not want to see the nation redefine itself around the blood-and-soil concept of “Heritage Americans”, and reorient the mission of the U.S. Military around mass-expelling people who have less “heritage”.

In fact, I suspect that there’s a very deep and fundamental reason why most Americans — including most Republicans — reject the “Heritage American” concept. Yes, many think of America as a “propositional nation” — an idea defined by the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and so on. But I suspect that many also value American culture as a marker of shared nationhood.

When I was growing up in Texas, one of my best friends was born in Shanghai, and didn’t become a U.S. citizen until the age of 18. Culturally, he was a little different than me and the rest of my friends — his mom made dumplings instead of sandwiches, he taught me how to use chopsticks, he didn’t believe in God.

But in all the cultural ways that mattered to us, we were the same. We watched the same TV shows, played the same video games, and listened to the same music. We used the same slang, had the same attitudes toward school, and wanted pretty much the same things for our future. And yes, we believed in the Constitution, and American freedoms, and all of that stuff.

During the 2010s, during our nation’s great national collective freakout over race, I wrote to my friend and asked him if he had ever felt discrimination growing up, or if he had ever felt excluded from the majority. He responded that while once in a great while he faced a little racism from a few jerks, it didn’t dominate his experience. In terms of identity, he told me he just felt very American.

This kind of real, on-the-ground cultural affinity is something too nebulous for YouGov pollsters to ask about, and yet I suspect it’s deeper and more important than most of the more quantifiable markers of American-ness. America is a propositional nation to some extent, but we’re also a cultural nation, bound together by shared habits and attitudes and lifestyles and beliefs. What matters the most isn’t our family’s history in the country, but our own personal history. Shared life experience beats shared heritage in terms of building the bonds of nationhood.

I recently had an extensive online conversation with a dedicated natcon, and it was…weird. He told me that nonwhite Americans can never really be his countrymen. But he also talked a lot about Europe, and about his family’s history in the German Empire. It was clear his notion of “heritage” went way beyond America, and connected to deep ethnic and religious concepts that reach far beyond our nation’s borders.

It felt very foreign to me. When I compare that online guy with someone like my high school friend who was born in Shanghai, there’s no question which one feels more American. My friend can quote the Simpsons and Star Wars with me. We can go to a mall together with his kids, and see a movie and enjoy it together, with shared cultural context. We won’t obsess over his ancestors in China or my ancestors in Europe. What will matter most to us is our shared personal history in the United States of America.

The bond my friend and I share is rooted in the land, and in community. It is tied to the place we grew up — College Station, Texas, and the United States of America — that taught us to be who we are. In contrast, the bond that natcons feel with the German Empire, or with other natcons in Australia and the UK, or with the idea of heritage and whiteness and Christendom and so on, is what I call a vertical community. It’s a notional bond between a bunch of people who find each other online and decide that they have more in common with those distant people than with the people who live next door in physical space.

Vertical communities have always existed, but in the 20th century, place still dominated. Only with the coming of social media did vertical communities begin to make a serious challenge to traditional communities as the organizing social unit of humankind. But the bonds that those online communities create are thin; a human being cannot thrive forever on the sugar high of Twitter flame wars and Facebook likes. The physical world draws us inexorably back to the places we live, and the people who live around us.

Right now, the MAGA movement is in charge of America. It is fundamentally an online creature — a weak bond between a bunch of people whom social media has taught to have the same notional enemies. In our division and our complacency, the American majority, who does not live for online hate memes, has allowed ourselves to put people in power who would tear up our actual heritage in the service of those memes. But eventually, no nation ruled by the Extremely Online can thrive, and I think my countrymen are starting to realize that.

Update: Matt Yglesias has a good post about how National Conservatism is out of step with American history:

The genuflection from the tech leaders was absolutely, fundamentally anti-American. If there is one thing, one ideal, that should be at the core of what binds us it is that we bow to no king. We need more elites remembering that (and showing some goddamn spine).

I really enjoyed this piece Noah and I hope you're right in your optimism. But looking on from Europe - both with our own history and experiences and with an outside view on the US - I worry.

A few general thoughts:

• Reagan’s line is powerful, but it isn’t unique to America anymore. Many European countries have also become hugely more propositional in recent decades. This may be hard to see / feel from the US at times, but it's really a sea change (and there's also a bit more complexity to their historical identity formation, but that's beyond this post).

• I would strongly contest your claim that these types of vertical communities are a new phenomenon. Some good examples of very powerful enduring vertical communities well beyond place and geography are the European aristocracy, religious sects and even religion more generally (from Calvinists to Puritans to world religions), but also Renaissance intellectuals, Enlightenment scientists and many more. All created strong identities that went far beyond geography and often very deliberately tried to distinguish themselves from their immediate surroundings. And that's also why I worry that these ties and imagined vertical communities might actually prove way stronger than you think. The idea of whole nations tied so closely to place formed really strongly in the 18th–20th centuries. It's not certain at all that this will easily and quickly prevail in the coming years over other streams.

• An additional thing that deeply troubles me is how much of the language and concepts first used by the woke movement - “allies,” “heritage,” hierarchies of groups and what they are “due” - is now being copied by the far right. And arguably, they have a way more powerful and terrible way to use and leverage it. That was always the risk and why it was so dangerous for progressives to move into the territory of group-based identity and rights. Now we see that come due and progressive public intellectuals have prepared the ground for these ideas in America.

Would be curious to hear your thoughts on this.