Wealth is partly imaginary

And crypto wealth is more imaginary than most.

We’re all having a lot of fun laughing, or perhaps crying, at the ongoing saga of FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried. John Ray, the CEO who wound down Enron and who just took over FTX to do the same, says the latter is far worse. The crypto exchange had basically no internal controls, or even basic bookkeeping. There’s also some evidence starting to emerge that SBF may have simply stolen much of the customers’ money that he appropriated from FTX, rather than simply funneling it into bad investments (if so, I would imagine he still has some of it stashed somewhere). The whole thing will make a great movie someday, though I doubt the movie will be as crazy as the reality.

But this piece of the dark comedy especially caught my eye:

How can it be that a bunch of assets that were marked down as being worth $5.5 billion — billion with a B! — were actually worth only about as much as a used laptop? (Update: Actually it’s marked as being worth $659,000, not $659, but this doesn’t change much!) Well, part of the answer here is that SBF was blatantly lying, but part of it is just the nature of how we measure wealth.

Back in June, I wrote a post in which I attempted to explain this:

Basically, only some small shares of an asset get traded. But we value the entire asset at the price that those shares trade at. This is called mark-to-market accounting. And it means that the amount of cash you could sell an asset for is different from the value that your asset is logged as. Here’s the example I gave in that post:

[I]magine if one guy (let’s call him “Noah”) owned 999,000 of the shares of Noahcorp. The price of Noahcorp shares — and therefore, the value of Noah’s wealth — would be determined by the remaining 1000 of the shares that did get traded. So if the price is $300 per share, then Noah’s wealth is $299,700,000.

But now imagine that Noah tried to sell all his shares of Noahcorp at once. The price would probably go way down…So Noah won’t get $300 a share. As he keeps selling more and more shares, the price will go lower and lower. By the time he sells all his shares, he’ll have much less than $299,700,000 in cash.

We often use the word “liquidity” to describe this phenomenon, but that word isn’t really up to the task. “Liquidity” officially means how easy it is to sell an asset — i.e., how easy it is to convert it to cash. But “easy” can mean lots of things. Your house is illiquid because it takes you a long time to find a buyer, but at the end of the day you’ll probably get about the amount the appraiser says it’s worth. Most publicly traded stocks, on the other hand, are considered very liquid because they get traded very frequently and it’s quick and easy to find a buyer for a few shares. But if someone tried to sell a very large number of shares in a short space of time — say, 40% of all the outstanding shares of Netflix — it would be very hard to find enough buyers to buy all of those shares. The only way to do it would be to drop the price a lot.

On paper right now, as of this writing, Netflix is worth $131.4 billion dollars. Suppose you had 40% of that. On paper, that amount of stock would be worth $52.56 billion. But if you tried to sell all of that quickly, you would not get $52.56 billion in cash — you would get a lot less, even though Netflix is considered an incredibly liquid stock.

Nor is it really possible to know just how much less you would get. We can measure the price impact of selling just a few shares of Netflix, but that doesn’t tell us much about the price impact of selling a whole lot of shares. In other words, it’s just unknowable ahead of time — the only way to know how much cash you really can get is to try to sell it and find out.

And that’s for the most liquid stocks in the world. Imagine you have a stock where only a very few shares ever trade, and there aren’t many people interested in buying or selling that stock. The difference between that stock’s mark-to-market value and the amount of cash you could raise in a fire sale is even bigger than for Netflix.

Among other things, this means you can raise the value of your company — and thus, raise your paper wealth — by issuing only a very tiny amount of stock (the amount you issue is called the “float”). A very tiny amount of stock costs only a very tiny amount of money, so a few people might buy it just on a lark. And this can make you very rich on paper, even if the actual amount of cash you could get for your paper wealth is quite low. A few years back, Alex Rampell of Andreessen Horowitz pointed out how this works in the IPO market:

Of course, if this is a problem in stocks — which are very transparent, highly regulated, and widely understood — imagine how much worse this problem is in crypto, where almost every asset is new and there’s extremely little oversight or transparent disclosure. SBF marking his $659k of crypto as being worth $5.5 billion was probably largely just a lie, but there are plenty of crypto fortunes out there that are not lies — they’re just fantasies generated by mark-to-market accounting in a highly illiquid market.

It’s also worth noting, of course, that very low liquidity, combined with opacity, also makes it much easier to manipulate a market and boost your paper wealth using fraud. Here’s how that works:

But anyway, many of the super-rich crypto people whose fortunes you see reported in the press could only raise a small fraction of that amount in cash — not because they’re frauds or because their companies are bad (though these may also be the case), but simply because there aren’t many buyers out there for their tokens. And although this discrepancy is less severe for stocks and bonds and real estate than for crypto, it still exists. Much of the wealth in the world is hypothetical. Notional. One might even say imaginary.

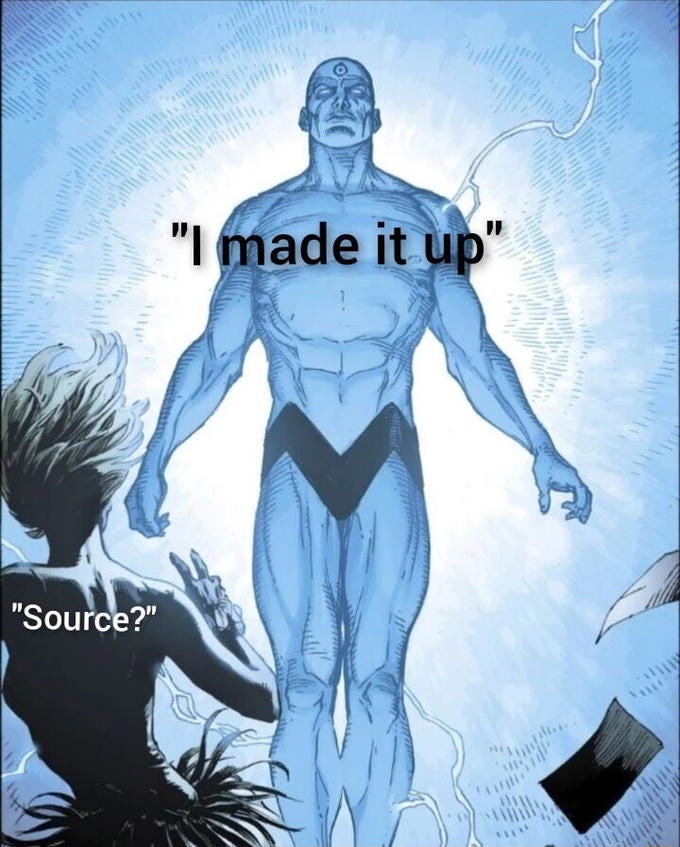

Now at this point you might be thinking: “Isn’t there a better way to do the accounting, so that people’s wealth reflects how much cash they could actually raise?”. And the answer to that question is “not that we know of”. To borrow a phrase from Churchill, mark-to-market accounting is the worst form of accounting, except for all the others that have been tried. In the runup to the 2008 financial crises, many banks created highly complex products that were so byzantine and so bespoke that there was almost no market for them at all (remember “CDO-squared”?). Because these assets were almost never actually bought and sold, banks were unable to use mark-to-market accounting to value them at all, so instead they used something called mark-to-model accounting instead. These models turned out to be very bad, leading to the assets being massively overvalued. Basically, instead of asset values being determined by how much people would actually pay for them, it was this:

And unlike whatever SBF was doing, this was perfectly legal. But it lead to catastrophe, when those assets had to be actually sold in the crisis. Only the intercession of Congress and the Fed saved those banks from being brought down by their model-based accounting.

So no matter what accounting system we choose, a lot of the wealth in the world is imaginary — it does not reflect how much cash people could raise, and thus it does not reflect how much real consumption their wealth would allow them to do.

OK, so why do we care about any of this? Players in the financial world already know about liquidity, and they hopefully take it into account when making important decisions such as how much collateral to demand for a loan. As long as lenders and such aren’t being defrauded, why does it matter if paper fortunes get marked up the stratosphere?

Well, one reason is that wealth inequality has become a hot-button political issue in recent years. In the past, pundits and policymakers focused mainly on income inequality, but the work of the economist Gabriel Zucman, and the advocacy of politicians like Bernie Sanders, has recently shifted the focus from income to wealth.

As Zucman & co. like to point out, wealth inequality is greater than income inequality, and has risen by more in recent decades. Thus, the shift towards a focus on wealth inequality has helped to raise the level of concern over inequality in general.

But why has wealth inequality increased so much? The stock market has a lot to do with it. Since 1980, housing wealth has stayed about the same as a share of national income, but stocks — which are mostly owned by wealthy Americans — increased pretty substantially.

This is especially true for the people in the top 0.01%, whose share of the nation’s wealth has increased so dramatically since 1980. These people’s fortunes consist mostly of stock in their own companies (or, since the creation of crypto, their own companies’ tokens). The wealth of average folks, in contrast, tends to be in stuff like pensions and houses, where the discrepancy between paper and cold hard cash is much less.

Why have stocks gone up so much? Partly because corporate earnings have gone up, which may in turn be due to monopoly power. But a lot of it is just the fact that investors are willing to pay a lot more for U.S. stocks these days, relative to their earnings. Here’s the Shiller PE ratio (also called CAPE), which measures how “expensive” stocks are relative to the profits of companies:

When this number goes up, mark-to-market accounting inflates the fortunes of the 0.01% above and beyond the actual profit-making power of the companies they own.

In other words, some piece of the enormous increase in U.S. wealth inequality is only on paper — it’s an artifact of the weird definition of “wealth”, and of the high valuations of the U.S. stock market, rather than an increase in the inequality of the amount of real consumption goods that people can afford to buy.

Crypto only exacerbates this paper inequality. Even setting aside SBF’s fraudulent billions, and the other frauds in the space that are yet to be discovered, many of the “whales” who own most of the world’s $835 billion of notional crypto wealth are highly illiquid.

This doesn’t mean that the people you think are rich aren’t really rich — most of them are. Nor does it mean inequality isn’t a problem in America, or that it hasn’t increased — it is a problem, and it has increased. But perhaps the imaginary nature of some of this newfound paper wealth should temper our outrage just a bit.

Wealth is just sort of a weird concept. It will always be a little bit of a fugazi. Sometimes a little more than other times.

It’s $659,000 I believe (he has a later tweet). Still a long way off $2.2bn!

The Jane Austen manner of describing wealth as x amount per year is much simpler.