We aren't going to defund the police (nor should we)

But we might end up with some good reforms.

The anti-police movement is losing.

One year ago, tens of millions of Americans (including Yours Truly) poured into the streets to express their anger at police brutality and racism after the murder of George Floyd. It was probably the largest protest movement in the country’s history — an epochal, generation-defining event. A little over 80% of the protests in May and June of 2020 were peaceful. But the level of police violence involved was striking. Hundreds of videos from around the country showed cops using aggressive and provocative tactics against peaceful protesters. Perhaps the most iconic scene was when Buffalo police shoved a 75-year-old man onto the ground, giving him a brain injury.

That police violence woke Americans up to the fact that something is broken in our culture of policing. Our law enforcement officers are poorly trained compared to those in other rich countries. They have been inculcated with a “warrior” culture that effectively teaches them to view the public as an enemy force and makes them intolerant of the slightest perceived challenge to their authority. Lyman Stone — a conservative! — made a persuasive, data-driven argument that police violence rose sharply since the year 2000, even as violence in general (and violence against cops) declined.

From this outpouring of justified anger came calls for specific policy reforms, like ending qualified immunity. But the protests also spawned a movement to abolish or defund the police. A whole set of beliefs and folk knowledge sprang up around this movement — the idea that police are an outgrowth of slavery, the belief that cops don’t actually stop crime, and so on. Young people whom I like and respect supported this movement and espoused these beliefs. They envisioned a world without cops, in which social services and an inclusive society reduced the impetus for crime, and unarmed responders learned to de-escalate situations. Some even saw communities organizing for their own mutual defense instead of contracting it out the government.

But a year later, this movement is losing. Minneapolis, the city where George Floyd was murdered, is spending $6.4 million to hire dozens of new cops after a number quit or went on medical leave. After cutting police budgets in 2020 — in response to the Floyd protests, but also because of the immense strain that Covid put on local finances — most big cities are now boosting law enforcement spending once again.

What happened? Was the outpouring of anger against American cops an ephemeral thing, a product of lockdown stress and the euphoria of a nationwide mass movement? I don’t think so. Instead, I think what happened was that policing is simply a very hard problem — while the situation is bad, radical solutions to that situation are all even worse.

“Abolish” became “defund”, and “defund” is dying

One early harbinger of the anti-police movement’s failure is how quickly the slogan “abolish the police” turned into “defund the police”. Supporters of the movement will insist very strenuously that these are the exact same thing, and that they have given not an inch of ground. But everyone knows this is false. “Abolish” is a bold, visionary word that hearkens back to the abolitionist movement against slavery; “defund” is an awkward, wonkish term that focuses narrowly on fiscal measures. It’s clear why this slogan was changed — “abolish the police” scared the shit out of people, especially after the giant flaming disaster that was Seattle’s “autonomous zone”. Meanwhile, “defund” potentially created a bigger tent by being somewhat of a Rorschach test — squishy fence-sitters could tell themselves it meant modest budget cuts even as the diehards knew that it really meant abolition.

This gambit might have won a little bit of support, but overall it was a failure — everyone who had any significant amount of trepidation about radical police reforms interpreted “defund” to mean “abolish”, just like the diehard supporters did.

And both defunding and abolishing the police are incredibly unpopular policies. Here are the results of an Ipsos/USA Today poll from March of this year:

“Defund” polls better than “abolish”, but only slightly. On net, Black people are against “defund” and strongly against “abolish”. Political independents are overwhelmingly against both.

The poll also finds that Americans tend to trust the police as an institution. Look at the wording of this question — it’s not about general trust, it’s specifically about which institutions people trust “to promote justice and equal treatment for people of all races”, and the cops still come out ahead, especially with political independents:

It’s not clear why this is the case, but the most likely reason is that people know that police do lots of good and useful stuff. The clearest evidence is that other rich countries all have plenty of cops — in fact, many have substantially more police per capita than we do. Presumably they are there for a reason.

The anti-police movement promotes a caricature of cops as primarily dedicated to racist violence — all George Floyd, all the time. But when law professor Rosa Brooks worked as a part-time police officer from 2016 to 2020, she found something very different:

I see two profound truths that are in tension with one another. One is that policing in America perpetuates extremely unjust socioeconomic divisions, particularly along the lines of race, and policing in America is stunningly violent compared to policing in most other countries. That’s a profound truth.

But there’s another profound truth, which is that the overwhelming majority of police officers will never even point their weapon at another human being during their entire career, much less shoot someone.

In DC, at least, the average cop only arrests someone about once a month. They spend most of their time responding to calls. You’re taking sick people to the hospital. You’re doing CPR on people who overdose. You’re trying to find a kid who’s missing. You’re trying to help protect a victim of domestic violence or comforting a robbery victim. This is a profound truth, too: A lot of cops spend a lot of their time responding to people’s requests for help. Many cops never use excessive force, and they’re courteous and kind and thoughtful, but all of that good doesn’t cancel out the abuses or the structural problems.

It’s hard to talk about this in our polarized discourse. You’re either locked into “Police are heroes and fuck you if you think otherwise” or it’s “Cops are brutal racist pigs and they exist to kill Black people.” These are both wrong.

This doesn’t sound like the kind of institution we should abolish; it sounds like the kind of institution we should reform.

And it’s far from clear that defunding will produce any kind of positive reform. My general impression is that even for the fence-sitting moderates who don’t equate “defund” with “abolish”, there’s the sense that threats of defunding are the only way to wring reforms and concessions out of police departments that have grown too politically powerful for city governments to control by normal means. But as any economist knows, a threat only works if it’s credible — if you can follow through on it.

And following through on the threat of defunding could be very bad. First of all, it might make the police even worse. As Tyler Cowen points out, police officers in many cities are not especially well-paid; if you pay cops less, that means that the people who are attracted to the force will tend to be less educated people with worse outside options, who are attracted to the culture of machismo and unaccountability. Exactly the people we don’t want on the force.

But even more importantly, people are starting to realize — or perhaps, starting to remember — that police play a very important role in the reduction of crime.

Cops prevent crime

One of the most ridiculous canards believed and promoted by the anti-police movement is the idea that police don’t prevent crime. I hear this over and over on Twitter:

I suppose they have a mental image of a uniformed cop on the sidewalk seeing a crime in process and going “Oi! You there!” and running over to stop it. Certainly, that rarely happens. But even a moment’s thought will reveal at least two far more important ways that police prevent crime.

First of all, the existence of police deters crime. People who want to commit crimes will often stop themselves from doing so if they know there’s a good chance the police will come and arrest them later. This is so obvious that it shouldn’t even need explanation.

The data strongly backs it up, too. A 2017 review paper by economists Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary looks at the literature and finds:

There is robust evidence that crime responds to increases in police manpower and to many varieties of police redeployments. With respect to manpower, our best guess is that the elasticity of violent crime and property crime with respect to police are approximately −0.4 and −0.2, respectively. The degree to which these effects can be attributed to deterrence as opposed to [taking criminals off the street] remains an open question, though analyses of arrest rates suggests a role for deterrence.

This means that if you double the number of cops on the force, violent crime goes down by 40%! That’s huge.

This isn’t the result of one study; it’s a whole bunch. Nor are these simple correlations; they’re the kind of credible empirical studies that take advantage of natural experiments and try very hard to account for measurement error. Just to give one example, Steven Mello looked at the results of a 2009 federal policy that gave cities grants to hire more cops. Mello compared cities that just barely made the application cutoff for a hiring grant with cities that just barely missed that cutoff. He found that getting a grant caused police staffing to increase by around 3.2%, and crime to decline by 3.5% — a huge amount of bang for the buck!

Actually, a number of the studies surveyed by Chalfin and McCrary deal with programs that surge police into certain areas, instead of hiring them more for the long term. The effectiveness of these surges points to the second way police prevent crime — through their presence on the street. If you see a cop around, it makes you less likely to commit a crime. This is also why foot patrols — cops getting out of their cars and walking around — have been shown to reduce crime.

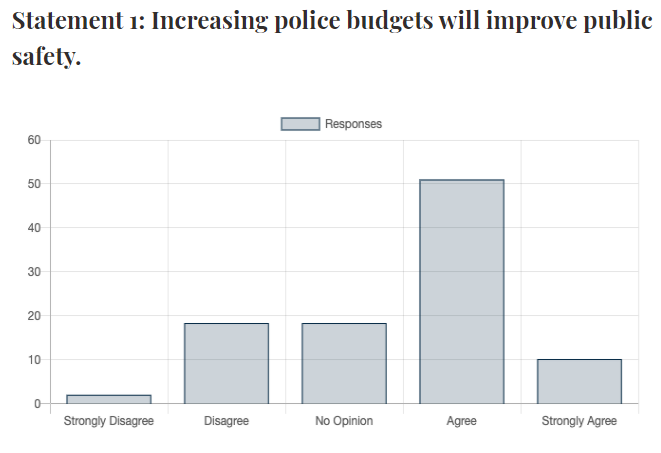

In fact, if you ask criminologists, they will straight-up tell you that increasing police budgets reduces crime. A survey called the Criminal Justice Expert Panel polled a bunch of respected criminal justice scholars in various fields and in various countries, and found that a substantial majority think that increasing police budgets will make the public safer:

Against this mountain of evidence and expert opinion, the anti-police movement has — what? An anecdote about a New York City police slowdown in which crime reports actually fell? Sorry, but data is data, and the systematic, carefully gathered evidence clearly shows that more police, especially more police on the street and in dangerous neighborhoods, really do reduce violent crime.

And that’s important, because America is currently getting a very painful reminder of what high rates of violent crime are like.

Violent crime is back

From the mid-1990s to the early 2010s, there was a huge nationwide decline in violent crime. In 2015 there was a major spike, but that mostly reversed over the following three years. But in 2020, violent crime soared — not all the way to the dark days of the early 90s, but far above the levels Americans have come to expect.

Violent crime numbers depend on reporting, and some crimes (especially rape) often go unreported. So it’s important to look at murder, which almost always does get reported. And murder absolutely skyrocketed during the pandemic year — 44% in New York City, 38% in Los Angeles, 50% in Austin, 71% in Minneapolis, 53% in Portland, 49% in Seattle.

There was hope that this was the result of the pandemic — fewer eyes on the street, economic stress and personal anxiety, and so on. But as the pandemic has abated and people have come out of their houses, the violence has remained stubbornly high. We can hope that this monster surge fades the way the smaller surge in 2015 faded, but no one really knows how likely this is. Crime surges don’t always fade, as evidenced by the stupendous rise in violence in the late 1960s and early 1970s that ended up lasting for 25 years and costing hundreds of thousands of lives. Even criminologists who study the great crime decline now think that happy era might be over.

(What about lead, you ask? Hadn’t we found that the great crime decline was caused by the effects of childhood lead exposure? Well, lead is certainly bad for you, and it probably does increase criminal behavior. But we must always remember that statistical significance is not the same thing as explanatory power — just because we can detect an effect doesn’t mean that effect explains everything. And a meta-analysis of papers on the lead-crime hypothesis found that it probably explains less than a third of the crime decline in America.)

Especially gut-wrenching is the wave of racist attacks against Asian people in America. The Atlanta spa shooting is the biggest and most well-known such attack, but it’s only one of many. ABC correspondent CeFaan Kim has done an excellent job of documenting the violence, so if you want to scroll through the long litany of recent attacks, check out his Twitter feed. Here are just a couple:

The list goes on and on and on. Film director Joseph Kahn has a whole thread just of Asian people getting attacked on the New York subway.

Even more than the startling numbers, this outpouring of random brutality seems to have shocked the country. The attacks are making Americans remember why hiring more police used to be among the most popular policies in the country.

In other words, police exist for a good reason, and Americans know it. We will not get rid of them.

But that leads to the painful question: To what degree was the urban revival of the 1990s and 2000s bought at the cost of police abuses? And how can we sustain our great cities while minimizing those abuses?

How do we walk away from Omelas?

In her famous 1973 short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”, Ursula K. LeGuin describes a liberal paradise, whose freedom and happiness depends on the torture of a single abandoned child. It’s a powerful allegory — an indictment of the brutal utilitarianism that would choose to provide for the greatest number at the expense of a minority.

The question is: Are the great Liberal Cities of modern America just a form of Omelas? The years since 1990 have seen a dramatic urban revival, especially in coastal metropolises like New York City and Los Angeles. The big crime drop was a big part of that, since it allowed high-earning professionals and their employers to move back into the inner cities after decades of abandonment and neglect. Writer Will Wilkinson declared in 2017 that these cities are proof that “the liberal experiment works”.

But if police are essential to crime reduction, and crime reduction was essential to the liberal experiment, was that success bought at the expense of the victims of America’s broken policing culture?

Maybe so. And that means we can’t just go back to the way things were — we can’t just say “Oh well, I guess we need cops to prevent crime”, and just throw money at the old system and let it do its thing. Police won’t be defunded, but they definitely need to be reformed.

And despite the anti-police movement’s confident pronouncements to the contrary, there are ways to reform policing in America. Camden, New Jersey fired its police department and then rebuilt it from the ground up, bigger and more professional than before; crime fell by a huge amount. St. Cloud, Minnesota has worked hard to integrate police with the community rather than set them up in opposition. Part of that involves creating Japanese-style police boxes where the cops can have a permanent but peaceful presence on the street. This idea has been catching on among some friends of mine:

Another idea is to shift traffic stops away from cops and toward unarmed responders. Berkeley is experimenting with this concept (which was partially the brainchild of the excellent activist Darrell Owens). Traffic stops are one area where solid evidence of police racism exists, and even minor stops can easily lead to deadly altercations. A related idea is to send mental health professionals to answer some 9-1-1 calls.

Of course, training for cops should improve, and the profession should become more professionalized. That will almost certainly involve raising salaries — the opposite of defunding the police.

As for what the cops should be doing more of, there’s a good argument that they should be solving more crimes. The clearance rate of major crimes in America is abysmally low. Shifting police work from traffic stops and mental health calls to detective work would help convince American communities that the police really will help them and dispense justice — and thus discourage Americans from taking their safety into their own hands with personal acts of violence. Note that hiring a lot more detectives will require, once again, the exact opposite of defunding.

And none of this should discount the importance of improving social services! Sure, police do prevent crime, but social services prevent crime too; these are complements, not substitutes, and they should be part of a multi-pronged approach. The Criminal Justice Expert Panel strongly agrees:

And finally, police accountability has to improve. Ending qualified immunity and weakening legal protections for police unions seem like the most promising ways to do that. Again, the experts are strongly on my side on this:

We’re not going to abolish or defund the police. Nor should we. But hopefully the "defund” movement has created some lasting impetus toward change in America that will allow actually sensible reforms to get done. If that happens, maybe one day we’ll thank the doomed “defund” movement for — pardon the pun — playing the role of “bad cop”.

The observation about a "warrior culture" that prizes total control of every situation, regardless of the stakes, seems to explain the most egregious incidents. The search continues for a snappy slogan that gets at the core idea of enlightened reform that doesn't sound wonky, flaky, or conservative triggering (which doesn't take much, it turns out).

I wonder if chalfin and mccrary had any idea their paper would get the traction it got. I could die happy if any work of mine got half the attention theirs did