Was the American Rescue Plan a mistake?

We'll never know for sure. But Dems' policy ideas probably ought to change.

They say “hindsight is 20/20” (or in the words of George H.W. Bush, “50/50”), but that’s not really true. Even long after a policy has had a chance to work, only some of its effects will be clear. So we’ll never really know if Biden’s big Covid relief bill back in March 2021 — the American Rescue Plan— was a good idea or not. It’s also not suuuuuuper important, because nothing like the ARP is likely to happen again in the near future, barring another pandemic (knock on wood). But it’s an interesting question, and the answer we ultimately decide to embrace could be important in Democratic politics and policymaking going forward.

I was a big booster of the American Rescue Plan when it came out. Not only did I see it as a natural extension of the successful CARES Act of 2020, but I was also happy that it included the expanded child tax credit, which I saw as the future of welfare:

What’s interesting is that unlike the CARES Act, Biden’s relief bill promises to make cash payments a permanent feature of our economy. The most important item, in my opinion, is not the $1400 checks or Pandemic UI or any of that stuff — it’s the child allowance. Under the new bill, families will get monthly checks for $300 for each child under the age of 6, and $250 for each child between the age of 6 and 17.If you have two kids, that’s between $6000 and $7200 a year! Officially this is a temporary program, but many people expect it to become permanent.

Essentially this is a pilot universal basic income program for families. It would be phased out at higher income levels, but that’s not really that much different than a tax-supported UBI. The key here is that there’s no work requirement or time limit — all you have to do is have kids.

I didn’t really see a danger of inflation. The reason was simple: The CARES Act hadn’t produced any inflation to speak of. There was evidence that people simply saved the cash they got in 2020, using it to bolster their household financial positions instead of going out and spending it. Why, I reasoned, should getting cash in 2021 be any different? There was still a pandemic on, after all. So I wrote the following when the ARP came out:

As I wrote in an earlier post, COVID relief mostly isn’t fiscal stimulus. It’s disaster relief, which is really a kind of retroactive social insurance — the main purpose isn’t to pump up GDP, it’s to prevent a natural disaster from redistributing wealth and income in huge, arbitrary, unfair, and devastating ways. It’s to make sure that if you lose your job or your income or your business due to COVID, you don’t find yourself starving or out on the street or without a nest egg for retirement.

In fact, it’s good that COVID relief is mostly not fiscal stimulus! If it were, then Olivier Blanchard and Larry Summers would be right, and it would put our country at risk of accelerating inflation. But they are wrong. Because people will either save most of their relief checks or use them to pay debt-like obligations like back rent, the fiscal multiplier on this spending will be low, and we won’t be at risk of inflation.

In retrospect, I was wrong, and Blanchard and Summers were right. But how wrong was I? A note by Òscar Jordà, Celeste Liu, Fernanda Nechio, and Fabián Rivera-Reyes of the San Francisco Fed from about two months ago makes the case that the ARP was responsible for almost all of our inflation problem. They note that U.S. Covid relief measures boosted disposable incomes much more than in most other rich countries; the U.S. was indeed among the most generous countries, if not the most generous:

And they note that U.S. core inflation in 2021 was also much higher than that of other rich countries:

Note that on these graphs you can see why I didn’t think the ARP would generate high inflation. The bump in disposable income from the CARES Act was about the same size, and nothing really happened in terms of inflation — at least, not immediately. It’s possible that the release of all the money people saved from the CARES Act eventually contributed to the current inflation.

But anyway, just showing that America had more generous spending and also higher inflation doesn’t prove that the former is due to the latter. It could have been for some other reason. America’s supply chains could have been less resilient, or we might have had more monopoly power, either of which might have amplified the effect of a demand shock relative to Europe or East Asia. Alternatively, higher demand might have been due to differing pandemic behavior — Americans deciding it was time to come out and spend even though Covid and its variants were still raging, even as people in other countries remained cautious. High demand could have been due less to relief spending and more to the Fed’s aggressive lending programs relative to other central banks. And so on.

To make their argument that relief spending was the main culprit, Jordà et al. have to invoke some macroeconomic theory. So they use a modified Phillips curve. Instead of assuming a relationship between inflation and unemployment (as standard Phillips curves do), they assume a relationship between inflation and disposable income. Using this assumption, they attribute pretty much all of the increase in inflation to relief spending:

This result has basically been hailed as established fact by much of the media, but it shouldn’t be. There are a number of reasons this result could be completely wrong (and this is no knock against the SF Fed authors; macroeconomics is always very assumption-dependent).

For one thing, a Phillips Curve that replaces unemployment with disposable income implies that monetary policy only affects inflation by raising or lowering disposable income. But when we look at the inflation of the 70s, or the disinflation of the 80s and 90s, we see very little movement in disposable income at all during these periods — certainly nothing comparable to the Covid spike.

The authors claim their modified Phillips curve fits past data well, but looking at this graph I’m not sure how that works.

Second, Phillips curves are notoriously hard to identify; this is why they’re usually just assumed. When Hazell et al. (2021) looked at U.S. state-level data to try to identify the slope of the curve, they found that it was very flat — and concluded that most big changes in inflation are therefore due either to supply shocks or to changes in expectations, rather than to the direct impacts of demand management policy.

Finally, Phillips curves assume a pretty rigid lag structure — meaning that something that boosts demand today is assumed to boost inflation X quarters from now. Jordà et al. use a four-quarter moving average of detrended disposable income to retroactively “predict” inflation. (This is basically how the account for the “pent-up demand from CARES Act spending” hypothesis.) And since spending from the CARES Act subsided in late 2020, and spending from the American Rescue Plan (and the December 2020 addendum to the CARES Act) peaked in early 2021, the kind of Phillips curve that the SF Fed authors use means that we should definitely start to see a decline in inflation by the second quarter of 2022. Instead, core PCE inflation has held steady:

This suggests that at the very least, the relationship between disposable income and inflation is a little more complex than the SF Fed note assumes.

So while I don’t think there was anything wrong or bad about the assumptions the SF Fed authors chose for their macroeconomic theory, we have to recognize that there are a lot of other possible assumptions out there. Bianchi, Fisher and Melosi of the Chicago Fed have their own note in which they show how different assumptions can lead to very different conclusions about the ARP’s inflationary impact. Obviously high inflation is the scenario we got, but Bianchi et al.’s examples show that we can’t decisively conclude that the ARP was the main cause. In fact, another note by Barnichon, Oliviera and Shapiro (also of the SF Fed) uses a more traditional Philips curve using labor markets as the measure of economic activity rather than disposable income, and find that the ARP’s impact is about 1/10 as large as Jordà et al. estimate for Covid relief as a whole:

There’s also the possibility that the ARP and CARES Act caused some inflation, but that the real damage came from a shift in expectations; when the Fed incorrectly assumed that inflation was from transitory supply chain disruptions, it convinced some American businesses and investors that the Fed was taking inflation less seriously, resulting in a shift in the Phillips curve. If that’s true, then Covid relief spending bears only a little of the responsibility for persistent inflation, even if it was the initial spark.

As I see it, the fact that America did get unusually high inflation should shift our priors in the direction of theories that predict that we would get higher inflation. But it’s not conclusive at all, and those theories will still need to prove their worth out of sample — in other words, let’s see how quickly inflation subsides before concluding they’re right about the ARP’s role. (It’s also notable that inflation is now accelerating in other rich countries, though this may be due to the supply shocks associated with the Ukraine war.)

Anyway, so far I’ve only talked about the costs of the ARP, and ignored the benefits. Obviously, if we want to know whether it was worth it, we need to know both. Yes, people are mad and pessimistic about the economy, but had we not splurged, would people be even madder and more pessimistic right now?

If we believe in a Phillips curve type model of the economy, then there’s a tradeoff between economic activity and inflation — inflation is basically the cost we pay to reduce unemployment and boost growth.

So how much did we boost growth relative to other rich countries? Well, by the third quarter of 2021, our recovery was ahead of our peers by about 1 to 4 percentage points.

That gap stayed steady through the final quarter of 2021, at least relative to the Euro area, and is projected to stay the same through 2022. Our real investment (gross fixed capital formation) was higher as well.

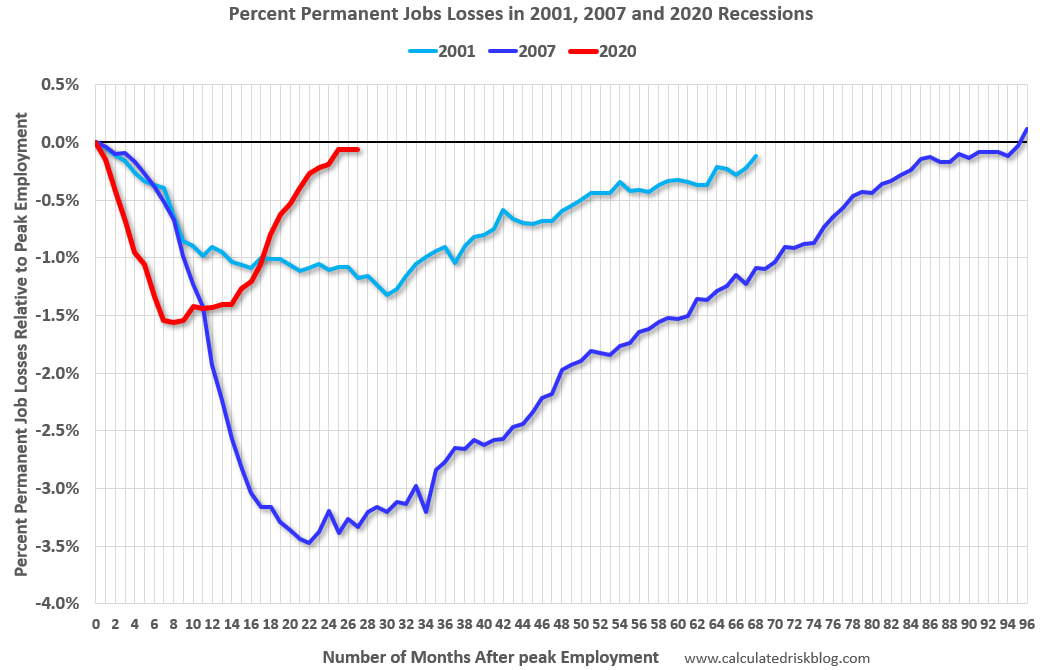

How about employment? Our employment level fell a lot less than headline numbers indicate (because many pandemic job losses weren’t permanent separations). But it was still a pretty deep hole, from which we recovered very quickly. Here’s a chart of permanent job losses, via Bill McBride:

Without the CARES Act, CARES follow-up, and American Rescue Plan, we might have had a much slower employment recovery. Just how slow, of course, depends on all that theory stuff.

But suppose GDP growth had been 3 percentage points lower. By Okun’s Law, that would have been about a 1.5% decrease in employment, or about 2.3 million more people out of work in 2021.

Would that tradeoff have been worth it? 2.3 million more employed people in exchange for 3% lower inflation over 2021?

It depends on what you think about the purpose of economic policy. If you’re more interested in helping the less fortunate, then maybe that tradeoff was worth it.

(It’s worth noting that because of inflation inequality, Dube’s assertion is too rosy; yes, real wages rose in 2021 for the bottom quartile if we use the headline inflation rate, but this was mitigated by the fact that inflation hits the poor harder.)

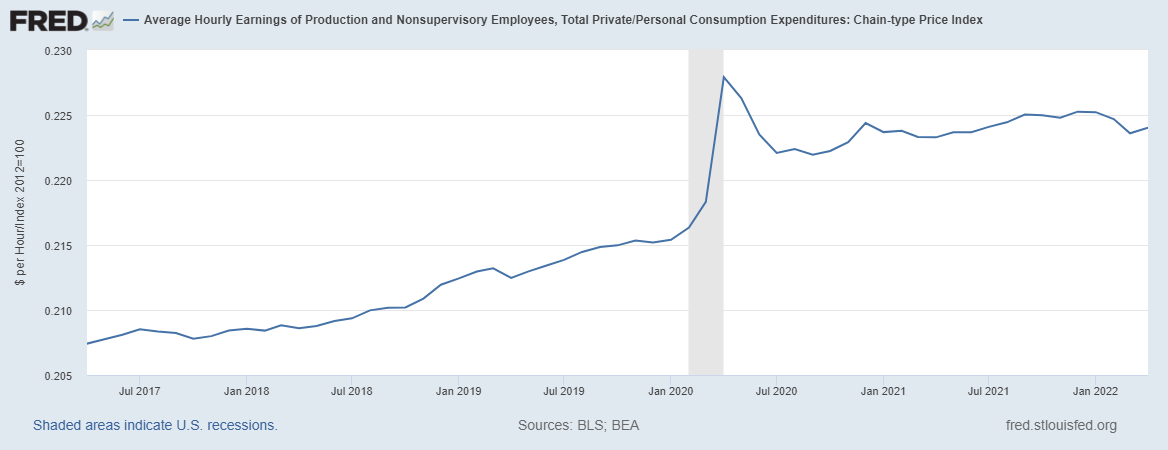

But the way we choose our leaders — one person, one vote — doesn’t emphasize the least fortunate; instead, it’s more about the median. And the median American’s real disposable income is almost certainly falling. Here are real average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers, which are probably now below their pre-pandemic trend:

Some of that is due to higher food and gas prices, but that’s also affected by government spending.

So in economic terms, it’s hard to tell whether the ARP was worth it, both because of deep theoretical uncertainty, and because it depends on whether you care more about the typical worker or the lowest-earning workers. But in political terms, it’s pretty incontrovertible that inflation has been a disaster for Biden and the Democrats, and will probably constrain government spending for years to come.

In other words, I’m definitely not ready to conclude that the ARP was a mistake. Knowing what we knew then, I still think it was the right thing to try. But the current bout of inflation should make us feel less positively about the ARP in hindsight. And it should probably shift Dems’ future economic policy ideas away from “just give people cash” and in the direction of “invest in things that increase the country’s productive capacity”. Redistribution should take a bit of a back seat to supply-side progressivism in the years ahead.

This is a bit off-topic to the current article, but is there any chance you'd do a similar writeup of what the Russia sanctions are meant to be achieving economically? At first we were told to stop buying oil and gas to starve Russia of money, and the ruble would crash. Now, it seems that the import sanctions are causing foreign reserves to pile up needlessly, with Russia having nothing to spend them on, but also that they will run out of reserves to prop up the ruble – and if it's the case that foreign currency can't be spent, does it matter that much whether oil and gas are embargoed.

I understand the general contours of the strategy – we don't want them to have money OR places to spend it, and we especially want to cut them off from parts needed for advanced manufacturing, which is what import controls do – but it would be good to hear from an economist how all these elements interact and what we should be seeing if they're working or aren't.

Too bad the child tax credit will be a victim of this as well.