War got weird

Half a century of IT innovation is now being used for destruction.

My basic thesis about technology is that it does two things. First, it gives human beings more power over to control our world. Second, as the price for giving us increased power, technology fundamentally transforms the experience of human life in unexpected ways that are difficult to comprehend even after the changes have already happened. In other words, technology weirds the world.

Military technology, unfortunately, is part of that. If you give human beings new capabilities, some of those humans are going to use those capabilities to try to conquer and kill each other. This doesn’t mean that we should restrain the development of technology out of fear that it’ll be used for military purposes — it seems to me that new technology has made humans steadily richer and happier over time without making war any more prevalent or destructive than it was in the past.

And in fact, I think this extends to military technology as well. Some Americans shy away from the idea of making tech for the U.S. military — for example, the Google employees who protested their company’s work for the Department of Defense in 2018. But Russia’s invasion of Ukraine should remind us all that the U.S. isn’t the only country in the world — rapacious, militaristic conquerors still exist, and it’s better to resist those countries than to not resist them. U.S. and European military aid to Ukraine has been essential in helping it fend off the brutal assaults of its much larger neighbor. This is a good thing. We should do more of this.

But the Ukraine war is also showing how recent technological advances have changed the nature of human conflict. In the 70s and 80s, innovation largely shifted from “atoms” to “bits” — our jet engines and rockets and vehicles are only a little better than they were back then, but our sensors and communication networks and information processing tools are vastly better. Recent wars had given us hints about the battlefield effects of the IT revolution — precision-guided munitions in Iraq and Syria, cyber-harassment of Iran’s nuclear program, drones triumphing over armor in the Armenia-Azerbaijan war, ISIS’ propaganda videos, and so on. But the sheer intensity of the clash in Ukraine, and the direct contest between U.S. and Russian technology, gives us a much clearer picture. And as always with technological revolutions, it’s deeply weird.

I am not an expert in military technology or in the subject of warfare in general, but here are a few interesting trends I’ve noticed while mainlining news from the battlefields of Ukraine.

Antitank weapons and drones

Eight years ago I wrote an article for Quartz boldly predicting that drone weaponry would cause a massive upheaval of society. That hasn’t come to pass yet, but drones are certainly being used more on the battlefield. Azerbaijan’s use of Turkish Bayraktar TB-2 drones to essentially wipe Armenian armored vehicles from the battlefield in 2020 was an unusual case; in Ukraine, modern Russian air defenses are having some limited success against the cheap, light remote flyers. But still, independent analysts find that Ukraine’s TB-2s are exacting a significant toll on Russian armor, immortalized in the now-famous Bayraktar Song:

The U.S. is also supplying Ukraine with Switchblade suicide drones (“loitering munitions”), so we’ll also get to see how effective those are.

But if drones have made the battlefield marginally more dangerous for armored vehicles, portable anti-tank weapons have been an absolute game-changer. Antitank guided missiles like the U.S.-made Javelin can kill armored vehicles at a range of more than 2 km, while lighter weapons like the British/Swedish NLAW are useful at shorter ranges. These and other portable weapons have been supplied to the Ukrainians in great numbers by the U.S. and Europe — more than 17,000 so far. That’s probably more weapons than the Russians have vehicles — if a Russian Battalion Tactical Group includes about 100 armored vehicles, and the Russians have sent 75% of their standing force of 160 BTGs into Ukraine, then the Ukrainians theoretically have the capability to blow up everything that Russia has sent into their country.

As long as they don’t miss much, of course. But the antitank weapons’ guidance systems appear to be so accurate that a large percentage of the shots hit their mark — one estimate early in the war guessed that 280 out of 300 Javelins fired had scored a hit. Even if the number is only half that, the Ukrainians seem to have enough firepower to devastate the bulk of the world’s third-largest military, simply by walking around on foot with 25-lb or 50-lb gadgets. They’ve already taken out thousands of Russian vehicles:

The effectiveness of these weapons feels like a game-changer. Portable antitank weapons have always been a big deal since the days of the bazooka, but information technology may have tipped the scales strongly in favor of this kind of tool. The night-vision system that allows a Javelin operator to see a tank far away at night, and the computer chips that guide the projectile unerringly to its target, are both modern advances. Armored forces can’t easily see the foot soldiers approaching, and even the thickest armor (supplemented with a “cope cage” on top of the turret) is no defense against projectiles programmed to seek out a tank’s weak spots.

This doesn’t mean that tanks and other armored vehicles are obsolete on the battlefield — active defenses, combined arms tactics, and other complex and expensive solutions may still be able to foil the Javelins and NLAWs. But it’s worth asking if doing so will be worth the cost. A Javelin costs $178,000; a Russian T-90 tank costs $4.5 million, or 25 times as much, and more modern vehicles with fancy anti-missile systems will cost even more. Even if new defenses get portable antitank weapons’ success rate down to 10%, the balance of costs will still be with the foot soldiers.

The U.S. Marines may have seen the writing on the wall; this year they will stop using tanks.

We could thus be looking at one of those epochal shifts in the way wars are fought. One example is the sinking of the British warships Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese aircraft in 1941, which heralded the end of surface ships as the kings of the sea. But an even better parallel might be the invention of the gun, which ended horse cavalry’s domination of the battlefield. I wrote about this in my 2014 article:

[I]magine yourself back in 1400. In that century (and the 10 centuries before it), the battlefield was ruled not by the infantryman, but by the horse archer—a warrior-nobleman who had spent his whole life training in the ways of war. Imagine that guy’s surprise when he was shot off his horse by a poor no-count farmer armed with a long metal tube and just two weeks’ worth of training. Just a regular guy with a gun.

That day was the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of modernity. For centuries after that fateful day, gun-toting infantry ruled the battlefield.

This process eventually culminated in World War 1, where machine guns and other weapons basically immobilized armies on the battlefield, resulting in years of grinding trench warfare. Tanks and other armored vehicles were invented as a response to that stasis; their thick sheets of armor allowed them to crash quickly over trenches and through hails of bullets and get behind enemy lines. Four centuries after horse archers became obsolete, rapid maneuver warfare returned to the battlefield.

What if this happens again? It seems unlikely we’ll go back to the trenches of World War 1. But people need vehicles to get heavy weapons and supplies around the battlefield quickly, and if these vehicles are very easy to destroy with cheap shoulder-mounted infantry weapons (and cheap low-flying drones), it might simply no longer be possible to execute blitzkriegs against a reasonably well-equipped foe without suffering unacceptable losses. Armored vehicles may no longer be a cost-effective tool for fighting wars.

That could be a very good thing in many ways. Artillery weapons like the ones that have been devastating Ukrainian cities are armored vehicles too (or are towed around by them), so if antitank weapons and drones sweep them from the battlefield that will make it harder to bombard cities.

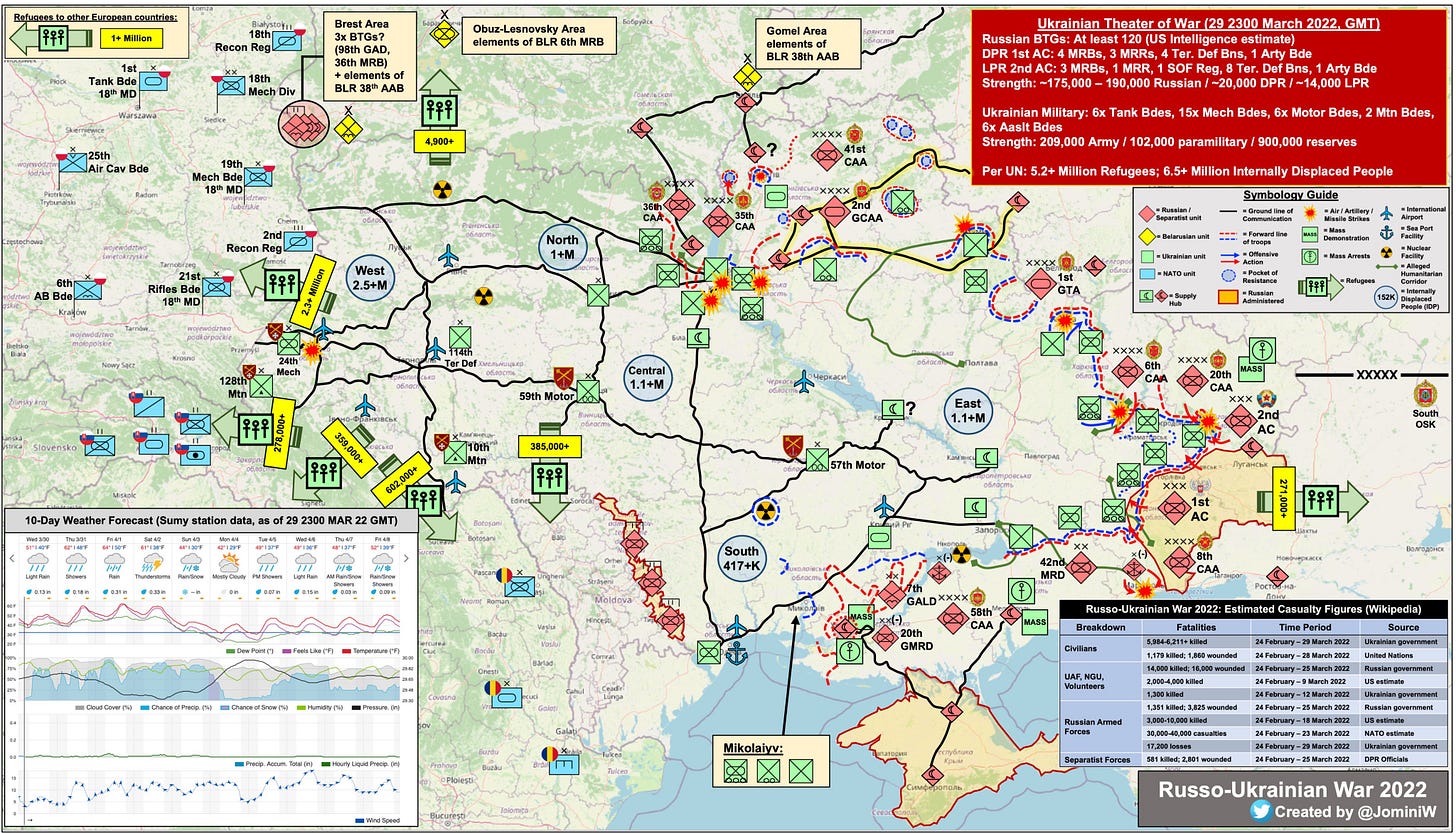

So what does the battlefield of the future look like? Perhaps less of a static front, and more like a game of cat-and-mouse, with slow-moving infantry and stealthy drones hunting each other down across a battlefield the size of the whole country. Already, maps of the Ukraine war are starting to look a little bit like this:

I was struck by how one Ukrainian officer described how his combination of drones and antitank infantry managed to stop a fearsome 40-mile-long armored vehicle column headed for Kyiv:

[Ukrainian Lt. Col. Yaroslav] Honchar describes these technological battles, and Aerorozvidka’s way of fighting, as the future of warfare, in which swarms of small teams networked together by mutual trust and advanced communications can overwhelm a bigger and more heavily armed adversary.

“We are like a hive of bees,” he said. “One bee is nothing, but if you are faced with a thousand, it can defeat a big force. We are like bees, but we work at night.”

Of course, the question then becomes: What happens when guidance and detection systems become so good that infantry themselves are both easy to spot and hit at great distances? One can imagine weapons like super-long-range versions of the Whistling Birds in the TV series The Mandalorian — guided bullets that seek out human targets and take them out unerringly over great distances. If that becomes a reality, what does war? A standoff fight between precision-guided munitions and air combatants? It’s interesting to speculate but very difficult to say. All I can promise is that it’s going to get weirder.

The internet, OSINT, and information war

If new IT-powered weaponry has transformed the modern battlefield, the internet has been no less of a game-changer. Crucially, both Russian artillery and cyberattacks failed to permanently knock out Ukraine’s internet infrastructure:

And when Russian cyberwarriors did manage to disrupt parts of the Ukrainian internet at the beginning of the invasion, there was at least one network they couldn’t touch — Elon Musk’s Starlink.

Using portable terminals, Ukrainians were able to sustain their connectivity even in the face of Russian cyberattacks and destruction of local infrastructure. Private intelligence analyst Bob Gourley called it “an engineering marvel”.

The internet has allowed both the Ukrainians and the Russians to do two important things. The first is propaganda (now sometimes referred to as “information warfare”). This used to be delivered via press releases; now it’s TikTok videos, memes, YouTube songs, Twitter dunks, and so on.

Russia has tried their best, assisted by an army of bots and another army of useful idiots in the West. They’ve even tried making deepfakes of Ukraine’s President Zelensky. But so far, the moral force of the Ukrainians’ cause, combined with Ukrainians’ own more savvy, Western-oriented online sensibilities, have delivered Ukraine a decisive victory in the war for Western hearts and minds. That, in turn, has kept arms and aid flowing, bolstering Ukraine’s battlefield success, which then makes it easier to keep winning the information war. In China, Russia’s messages have found a warmer reception, but so far China hasn’t shown any inclination to step in and save Putin’s failing battlefield effort.

The second big thing the internet has enabled is open-source intelligence, or OSINT. Basically, over the past decade or so the information technology industry has managed to equip a huge percentage of human beings with pocket supercomputers containing high-definition cameras and wired to a near-instantaneous high-speed unified global communications network. This has utterly changed the nature of battlefield intelligence, allowing both far-flung military units and civilian bystanders to identify vehicle and troop movements and losses on the ground, with the help of a global network of onlookers. Ukraine called on its citizens to report the locations of air defense systems. Russians went online to collect personal data on Ukrainian soldiers. An independent website called Oryx has become the go-to data source on confirmed equipment losses, with online enthusiasts helping to geolocate destroyed vehicles.

Intelligence is central to how wars are fought, which means that OSINT is changing everything. Bob Gourley lists some of the key developments:

A thesis I cannot prove but I believe: We are witnessing the world’s first war where open source intelligence is providing more actionable insights than classified sources.

In this war:

Tiktok provided direct evidence of the nature of troop and equipment movements.

Commercial imagery showed field deployment locations, field hospitals, then proof of movement to invade.

Dating apps provided indications of which military units are being deployed.

Twitter gave a platform for highly skilled deeply experienced open source analysts to provide insights.

Cloud connected smartphones with a wide range of capabilities throughout Ukraine gave direct tactical insights into how the war was and is being prosecuted.

Open source analysts are listening into and translating military communications.

Cybersecurity analysts and cyber threat intelligence companies are sharing indicators of incidents faster than ever and before any tipping and queuing by government sources.

Historians with great context on culture and history are more rapidly collaborating and sharing relevant insights.

Much of the above is supported by new tools and applications and collaborative environments for individuals and non government groups.

The internet is what has made this possible. For the first time, armies are not alone on the battlefield — the whole world is with them, hovering over their shoulders like a ghost, ready to help them, confuse them, cheer them on, denounce them or spread their legends. Every war, but especially a high-profile great-power war like this one, is now in some sense a world war.

(Update: Now we have details on how the Ukrainians are crowdsourcing the locations of Russian soldiers.)

Be prepared for more weirdness

So what lessons can we draw from the weirdness of modern IT-powered warfare, besides simply to marvel at the way technology continues to reshape the nature of human conflict? I think if there’s one lesson here, it’s that we need to be prepared for the surprises that modern warfare will bring. Instead of continuing to pour money into legacy combat systems treasured by vested interests, our defense department needs to focus on the technologies that are most likely not to prove to be expensive obsolete liabilities in the event of a real war. The Marines, who gave up their tanks, might be showing the way here.

But being prepared for miltech weirdness also requires spending money. Predictably, many progressives are decrying Joe Biden’s call for increased military spending even as pandemic-era social programs expire and the Build Back Better bill is stalled in Congress. But when it comes to defense spending, Biden is right and the progressives are both wrong and spectacularly ill-timed. It’s a bad look to want to slash American military preparedness when totalitarian dictators are launching invasions and leveling cities.

Furthermore, the technological surprises of the Ukraine war should teach us that military modernization is a process of diversification — it involves putting our eggs in a number of baskets, to make sure that whatever the successful weapons of the next war are, we have them in our arsenal. That means investing in a number of weapons systems and organizational changes, without downsizing our military during the process. And that will take money. Perhaps not much money — Biden’s proposed increases are barely larger than inflation — but some.

We can make a lot of educated guesses about the ways that war will get even weirder in the future (and there are many people whose guesses are much more educated than mine!). But the future of technology is never perfectly predictable, and with evil conquerors on the march, we need to be prepared for as many contingencies as we can.

>This doesn’t mean that tanks and other armored vehicles are obsolete on the battlefield...

The tank's problem is not anti-tank missiles by themselves. The same missiles would do a number on lighter platforms and infantry. Since armies want to attack and need to mass for it, there's a need for an attack platform. But tanks are highly visible while packing surprisingly little attack power. So the platform needs to evolve for the new needs. WW2 was also a period of rapid evolution, where both sides tried heavier and lighter tanks but in the end settled on 'medium' tanks.

I believe the same evolution would happen here. The medium tank just provides too little for its bulk. The tank will evolve back into two variants:

* A light vehicle, quite likely remotely or AI driven. Essentially a disposable glass cannon + detector. Enemy drones and infantry are welcome to expose their position by destroying these tanks. Or not and get detected anyway.

* A very heavy vehicle, for either specialized tasks (portable radar, combat ambulance, minesweeper etc.) or for tank-like outright breakthrough - which will require all the active defences etc. one can muster.

Very well researched and thorough article Noah. War is definitely getting crazier, last year marked the first time an AI drone likely killed someone without being specifically directed to--scary concept for both morals and our future. I wrote a semi-viral piece on it if you're curious.

Keep up the great work!