As we gear up for election season, a big debate is whether the U.S. economy is doing well or not. Biden supporters point to extremely low unemployment, falling inflation, and real wages that have started rising again. Biden opponents — including both conservatives and socialists — contend that the inflation of 2021-22 left such a severe scar on Americans’ pocketbooks that low consumer confidence is perfectly justified. Biden supporters counter that since inflation has come down — and was never as severe as in the 1970s — the anger over the economy is just “vibes”.

Basically, the Biden supporters are right; the U.S. economy is truly excellent right now. Inflation looks beat, everyone has a job, incomes and wealth are rising, and so on. But on the other hand, I can’t command people to simply stop being mad about the inflation that reduced their purchasing power back in 2021-22. People care about what they care about.

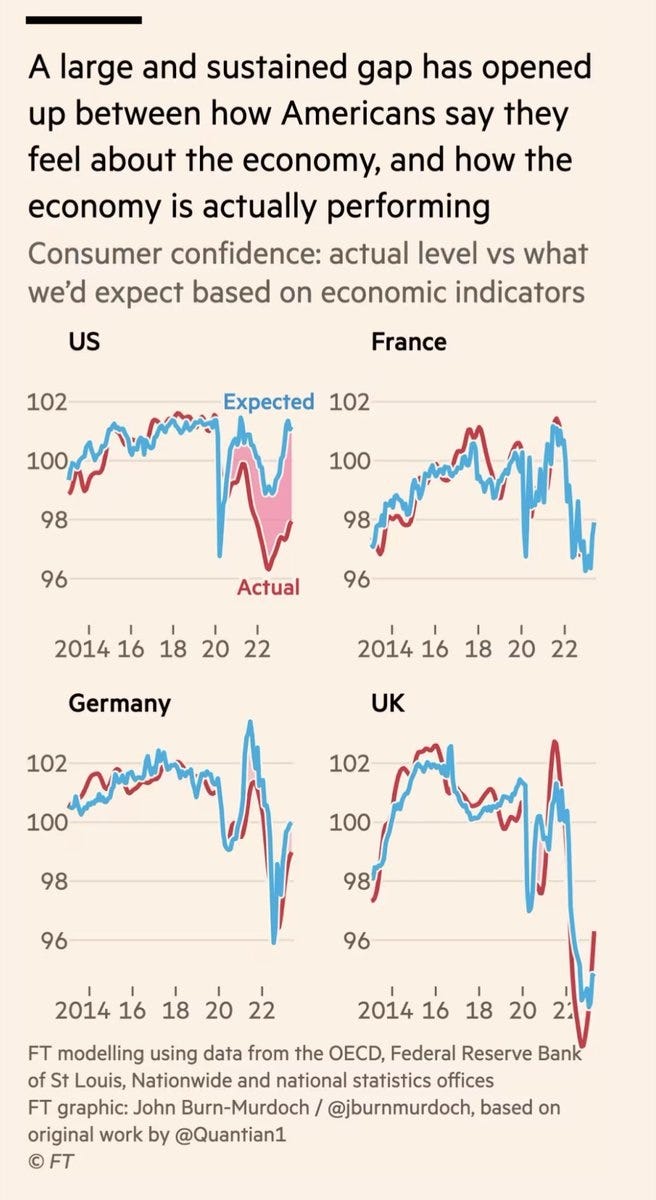

At the same time, though, I think it’s possible for negative narratives about the economy to take hold among the general populace and distort people’s understanding of what’s actually going on. For example, John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times recently found that consumer sentiment closely tracks real economic indicators in other countries, but has diverged in America since 2020:

Now this could be because Americans simply care about different things than Europeans; we might simply have started to really really hate interest rates since 2021, while Europeans didn’t. But a simpler explanation is that Americans’ negative sentiment is due to something other than economic indicators. And it’s possible that that “something” is a negative narrative — i.e., vibes.

For a concrete example, take this Twitter thread by a user called “deusexmoniker”:

I don’t want to pick on this one random Twitter guy and his non-expert analysis. Nor do I want to suggest that a random person’s Twitter rant represents American popular opinion. But I think the thread demonstrates how negative economic narratives can form a sort of gestalt impression that colors people’s views of the facts in ways that make it more difficult for them to decide whether they actually approve or disapprove of what’s going on in the real economy. So I want to go through a few of the man’s point here.

First, he claims that Biden ejected millions of kids from SNAP (food stamps) because of low unemployment (pardon the foul language):

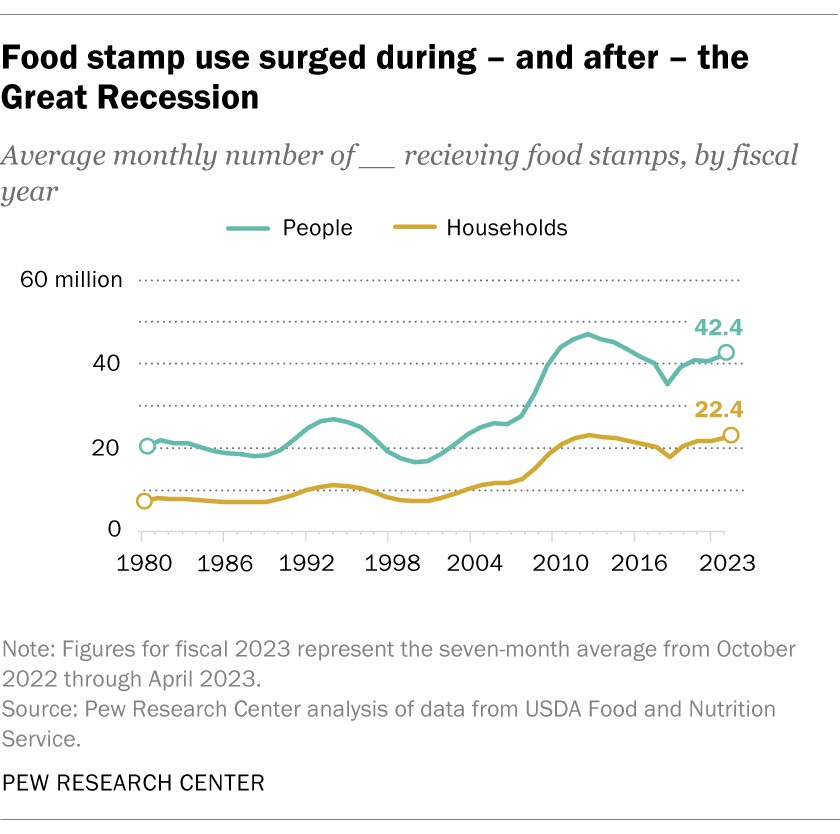

First of all, food stamps don’t work like this. The program has work requirements, which means that if you have a job, it’s easier to get food assistance, not harder. (I don’t think work requirements are a good policy, but that’s beside the point.)

Also, the number of people receiving food stamps has increased under Biden, and the number of households using the program is at a record high:

Now, if you wanted, you could use that as a negative economic indicator — “Look how many people need food stamps now!”, etc. But if you can just as easily take the same piece of data as a positive or negative indicator, that’s just a sign of the power of narratives to color our interpretations of the facts. “Deusexmoniker” incorrectly thinks food stamp use is falling, and interprets that as being indicative of the Biden administration’s cruelty. It’s just vibes.

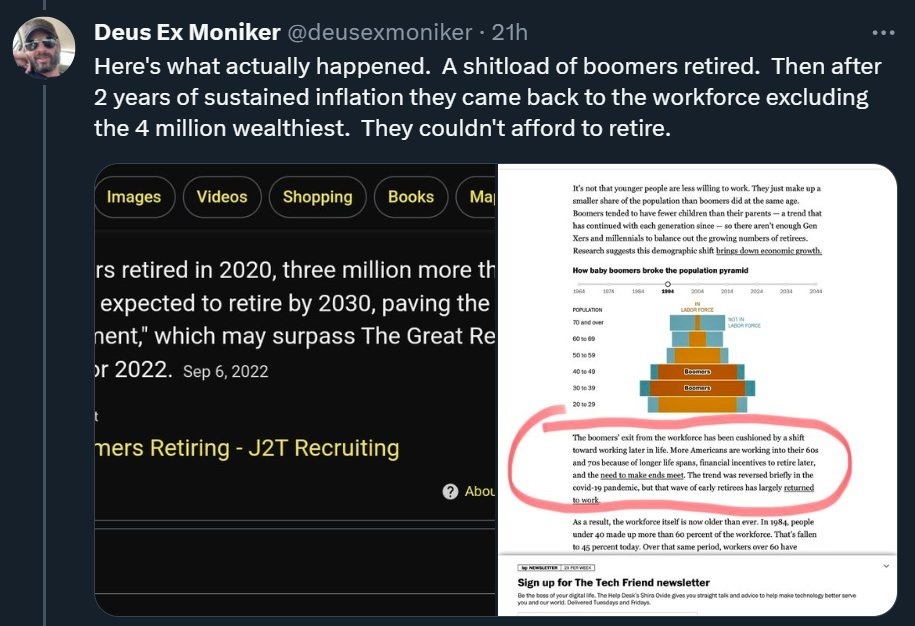

Deusexmoniker goes on to claim that unemployment is low because retirees have been forced back into the workforce by inflation:

But whether or not that’s happening, the prime-age employment rate — which only goes up to age 54 — is near record highs. That number isn’t affected by retirees:

But again, observe how a negative narrative can allow people to see any piece of data as being a sign of a bad economy. If inflation was low and millions were out of work, as was the case in 2009, do you think “deusexmoniker” would take this as a sign that people were rich enough not to work, because food and gas and rent were affordable? I highly doubt it.

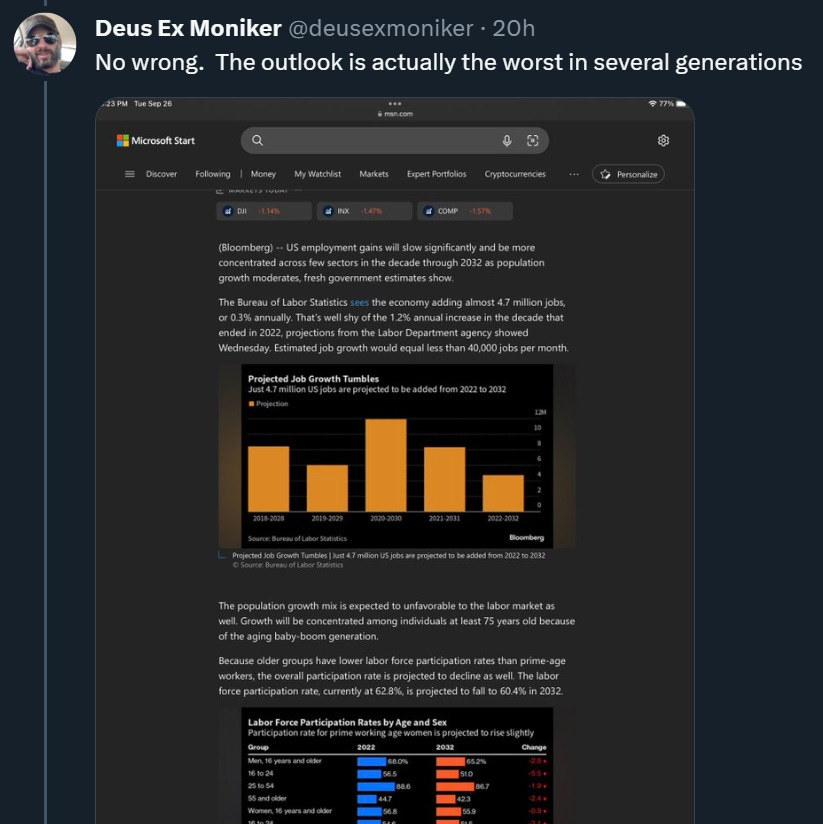

Next, the man cites a Bloomberg article to claim that the employment outlook is dismal over the next decade:

But in fact, the Bloomberg article does not paint this forecast as a sign of economic weakness. Nor does the BLS report that the Bloomberg article is reporting on. In fact, the slow projected job growth is a function of two things:

the fact that the economy has already reached full employment, so there isn’t much more room for increase there, and

the fact that the U.S. population is getting older and a lot of people are retiring.

Here, let’s let the BLS report speak for itself:

Slower projected growth in the population is expected to constrain growth in the civilian labor force over the projections period…This translates to a projected annual growth rate of 0.4 percent, slower than the 0.6-percent annual growth rate exhibited during the 2012-22 decade…

Total employment is projected to grow 0.3 percent annually from 164.5 million in 2022 to 169.1 million in 2032. This projected growth is much slower than the 1.2-percent annual employment growth in the 2012-22 decade, which was marked by strong recovery growth following the 2007-09 Great Recession and 2020 COVID-19 recession.

Once again, a negative overall narrative about the economy has caused “deusexmoniker” to interpret a sign of economic strength — full employment, i.e. less room to add jobs — as proof of economic weakness.

Anyway, the errors continue throughout the thread. He vastly exaggerates the number of workers in the U.S. who can’t afford housing and the number of people who report that they’re experiencing food insecurity. He argues that projected net job creation isn’t enough to keep up with population growth, ignoring the huge number of retirements that are also forecast. He claims everyone is behind on their credit card and car loans, when actually delinquencies are down. And so on. At every turn, his negative narrative about the economy drives his misinterpretation of the numbers.

As I said, my purpose here is not to rebut a random Twitter guy. My purpose is to point out that economic facts have limited power against narratives, since narratives can color our interpretations of facts, or entice us into believing things that aren’t true. When the Financial Times surveyed the American public about real wages, inflation, wealth, and median income, they found that negative beliefs were far more common than correct answers.

If you want to be upset over what’s happening to inflation, wages, wealth, income, etc., you have a perfect right to be upset. But at least you should know what’s actually happening. But lots of people simply don’t know.

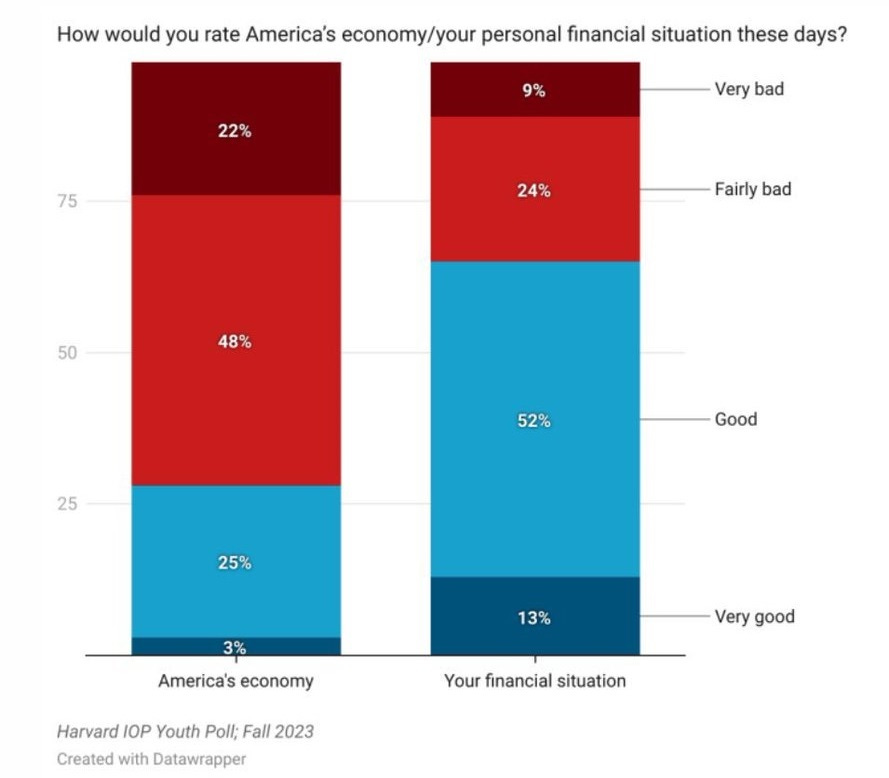

Some will be quick to interpret mistakes about the national economic situation as stemming from personal lived experience — the idea being that people care about their own financial situation much more than some abstract national statistics. But when you poll people about their personal economic situation, they’re much more positive than they are about the national economy as a whole. Here’s Axios back in August:

A majority of Americans think the economy is in bad shape, but at the same time say their own finances are good, finds a new poll out from Quinnipiac University this week…In the telephone survey of 1,818 adults Aug. 10-14, 71% of Americans described the economy as either not so good or poor. And 51% said it's getting worse…But 60% said their financial situation is good or excellent…"Can you be generally happy with your personal financial position and still think the economy is going in the tank? For a broad section of Americans, apparently so," Quinnipiac University polling analyst Tim Malloy said in a press release. (emphasis mine)

In other words, something is convincing a lot of Americans that the national economy is a lot worse than their own lived experience would suggest — and causing them to get the facts wrong in the process. That something is what commentators, for lack of a better word, are calling “vibes”.

Where do these negative narratives come from? Brian Beutler and Matt Yglesias both blame negativity bias — the fact that scary narratives get more attention than happy ones — for filling our screens with portents of doom. But of course negativity bias has always existed; it seems to me that this explanation only works if either A) people are consuming more news than before, and/or B) the replacement of traditional media with social media has exacerbated negativity bias. And since the weird break between economic fundamentals and consumer confidence appears to exist only in America, this explanation would require media’s negativity bias to be much less powerful in Europe.

Which leads me to suspect that although negativity bias is certainly a factor, something else is going on here. The fact that the problem is U.S.-specific suggests that either a special feature of American society and politics is at work here, or the American media and social media landscape differs from Europe’s in key ways. Since Europeans have Twitter and Facebook and TikTok too, and their newspapers and TV news shows aren’t that different from ours, I suspect U.S. social and political factors as the cause of the peculiar presence of negative narratives.

In any case, the question is how we commentators can fight the dominance of the vibes — not because we want to convince everyone that the economy is great, but because people need facts if they’re going to know whether the economy is good or bad. But I’m afraid that’s one question I don’t have a good answer to. Perhaps we should just keep relentlessly reminding everyone of the facts, while waiting for the populace to finally realize that economic fundamentals have improved.

Update: Here’s a poll of young Americans that reinforces the notion that negative narratives about the national economy are causing people to think the rest of the country is doing worse than they are:

Every guy is just out to dinner saying “Wow look at the price of steak! I mean I can afford it thanks to my last raise, but how is everyone else managing?” Meanwhile the restaurant is full because everyone got a raise.

The striking thing about that graph of public sentiment vs. economic indicators is that American public sentiment is almost perfectly in line with European public sentiment; the difference is that the US is doing well (at least according to the indicators) and Europe is not. That suggests to me that negativity bias might be a good explanation: Europeans and Americans are equally biased towards negative views, and those views just happen to be true there and false here.