U.S. state capacity is actually pretty high

A divided society is not the same as a declining nation.

There’s a widespread narrative out there that the United States is a nation in rapid decline — perhaps even terminal decline. In fact, I myself bought into and promulgated that narrative. For example, in March 2020, after witnessing the U.S. fail to scale up Covid testing, I wrote the following in Bloomberg:

But perhaps no advanced nation has responded as poorly as the U.S. Perverse regulation, a bungled government test and fragmented supply chains held back testing for crucial weeks, allowing the epidemic to spread undetected. Abdication of leadership by the federal government left the job of shutdowns to state and local governments…[T]he widespread nature of the failures suggest that coronavirus has exposed a deeper decline in the U.S.’s general effectiveness as a civilization.

And in a follow-up post three months later, I wrote about the idea of decline in more general terms:

The U.S.’s decline started with little things that people got used to. Americans drove past empty construction sites and didn’t even think about why the workers weren’t working, then wondered why roads and buildings took so long to finish. They got used to avoiding hospitals because of the unpredictable and enormous bills they’d receive. They paid 6% real-estate commissions, never realizing that Australians were paying 2%. They grumbled about high taxes and high health-insurance premiums and potholed roads, but rarely imagined what it would be like to live in a system that worked better…[T]he decline in the general effectiveness of U.S. institutions will impose increasing costs and burdens on Americans.

I wasn’t nearly the only person worrying about American decline, and many still do so. My friend Balaji Srinivasan, in a response to a post of mine, labeled it as a deficit of state capacity:

In fact, “state capacity” is a better way to frame it. “Decline” has an over-dramatic and antiquated sound to it, while also being fairly vague (Does it mean relative or absolute decline? Decline in what? Etc.). State capacity, on the other hand, is a fairly concrete concept in the social sciences — it means “the ability of a state to collect taxes, enforce law and order, and provide public goods”. Basically, it means the state’s ability to actually accomplish the goals it sets out for itself.

And this is an important but subtle point. In the two years since I wrote those glum posts about “decline”, I’ve come to have a much more nuanced opinion about U.S. state capacity. In those years, I’ve seen the U.S. make startling displays of effectiveness. And watching other states flounder has given me a new appreciation for U.S. effectiveness in previous years, which I took for granted before. This has convinced me that much of what appears to be declining state capacity is in fact a manifestation of social division — a country that can do big things, but usually doesn’t know what it wants to do.

Five recent examples of high U.S. state capacity

1. Intel on the Ukraine invasion

It was absolutely stunning how precisely U.S. intelligence agencies managed to predict Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. U.S. intel detected the Russian buildup starting in October, and as early as December, Biden was publicly predicting an invasion largely along the contours of the one that actually materialized. Right up until the last minute, people (myself included) thought Putin might pull back. To some, Biden’s constant dire warnings of an unprovoked attack seemed like an uncomfortable echo of George Bush’s insistence that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction. Then the tanks rolled in, and it turned out that the information Biden was getting was good.

Note that this wasn’t just a success of U.S. intelligence gathering; Biden’s strategic release of that intel was a political and diplomatic success. It helped the Ukrainians prepare more effectively to defend their country, robbing the Russians of any element of surprise. And it prepared Europe to unite in opposition to the invasion. Suddenly Russia is an international pariah, with even China trying to back away, while the U.S.’ European allies are more united than ever before. That’s a startling geopolitical success, and both skilled diplomacy and skillful intelligence gathering were part of that success.

So why did this case turn out so different from the massive debacle of the Iraq War? Maybe U.S. intelligence agencies simply got much better in recent years, but I think the main story lies elsewhere. Bush demanded a reason to invade Iraq, and he got one. The intel that claimed Iraq was pursuing nuclear weapons was flimsy, but Bush and his administration simply demanded that it be exaggerated and massaged in order to support a war. It wasn’t a lack of state capacity; it was bad decision-making at the top.

2. mRNA vaccines

When the Trump administration announced Operation Warp Speed, I was highly skeptical. It seemed massively unlikely that a safe, effective vaccine against a novel virus could be produced in record time. And yet we produced not simply one, but several. But not only that — the most effective vaccines, the mRNA vaccines, were produced using a new, previously unproven technology.

Operation Warp speed was, simply put, a triumph of government effectiveness. But our success didn’t stop there. When the mRNA vaccines came out, the news was filled with stories about how hard these vaccines were to produce at scale. We expected the supply chain for mRNA vaccines to be filled with bottlenecks. Given that we had failed to manufacture enough tests and masks in the early days of the pandemic, what hope was there to mass-manufacture this much more difficult product?

And yet we did. The predicted bottlenecks never materialized, and the Biden administration made an unprecedented and successful effort to roll the vaccines out to millions of Americans very rapidly. The U.S. initially zoomed ahead of almost every other country in vaccine administration. It eventually fell behind — not due to logistical difficulties or manufacturing shortages, but due to the antivax movement.

And the amazing success that the U.S. had in developing, manufacturing, and administering highly effective vaccines looks all the more amazing in comparison with China — the country that many people came to believe had the world’s highest state capacity after its early success with Covid suppression. China turned up its noses at Western vaccines and chose to invent its own. But its first attempts resulted in vaccines that were far less effective. Now it’s attempting to reinvent mRNA vaccines, but it’s having trouble manufacturing them at scale.

Score one for U.S. state capacity.

3. Covid relief

But vaccination wasn’t the only highly effective way that the U.S. responded to the Covid pandemic. Congress and the Trump administration came together in a remarkable display of effectiveness to pass one of the most generous Covid relief spending efforts in the world. As a result of programs like special unemployment benefits, U.S. poverty actually fell in 2020. Unlike many other rich countries, U.S. incomes actually increased during Covid:

And Biden continued those programs in his own Covid relief bill. That burst of spending did add to inflation, but it also enabled the most rapid economic recovery the country has ever seen, defying widespread predictions of a lost decade, new depression, or “K-shaped” recovery.

Of course, the Federal Reserve — a highly functional and capable U.S. government institution — deserves its share of the credit here too. As it did after 2008, the Fed took unprecedented action to stabilize the economy.

4. Wildfire fighting and Houston flood relief

Partly as a result of complacent policy, partly as a result of bad luck, and partly as a result of climate change, America has faced some major natural disasters in recent years. These included the unprecedented wildfires in California in 2020, and the “500-year flood” that hit Houston as a result of Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

But unlike in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina hit, the U.S. has dealt with these recent disasters in a highly effective manner. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection suppressed the massive fires effectively, even in the middle of Covid. There were no mass casualty events. California communities survived largely intact, and are now working on improving their fire resilience while the state works on improving forest management.

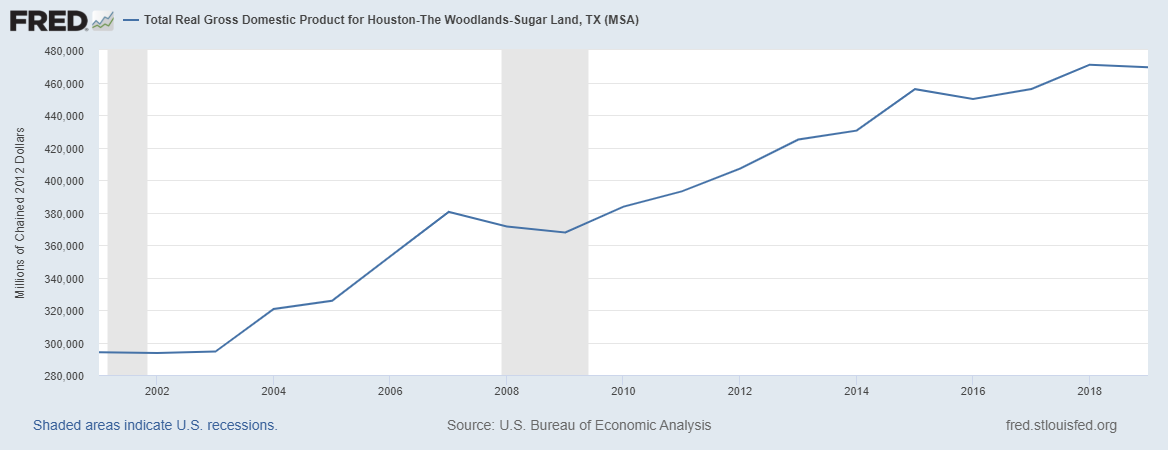

The response to the Houston floods was similarly effective. Though not well-prepared for a flood, Houston suffered only 14 deaths from rising waters, with 88 deaths from the hurricane in the state overall (compared to over 1800 in Hurricane Katrina). Photos of Houstonians helping each other were all over the news, while looting and other crimes were exceedingly rare. The city was not even close to destroyed, and its economy grew that year.

5. The War on Terror

The Iraq War was such a debacle, and the specter of the security state so scary in the early 2000s, that Americans tend to forget what a massive success the War on Terror was. But the U.S. managed to dismantle and degrade al Qaeda to the point where no one really thinks about it anymore — without al Qaeda ever conducting another major terrorist operation on American soil after 9/11. A combination of financial measures to freeze terrorist funding, an effective security state, good intelligence gathering, and the Afghanistan War swiftly destroyed an international terrorist organization that seemed to loom like a great shadow over the globe in 2002. People will remember the Afghanistan War as a U.S. loss, but in fact we did what we came to do, and mostly withdrew our troops shortly after killing Bin Laden and the rest of al Qaeda’s senior leadership.

And it wasn’t just al Qaeda that the U.S. defeated. ISIS was swiftly destroyed by U.S. military action, carrying out only a couple minor acts of “stochastic terrorism” on our soil and falling quickly to our relatively limited military action in Iraq and Syria. And ISIS’ fall seems to have discredited the entire idea of jihadist terrorism throughout much if not most of the Islamic world.

In other words, despite the willful blunder in Iraq, the U.S. managed to defeat the global threat of jihadist terror much more quickly and bloodlessly than fascism or communism was defeated in the 20th century.

Division vs. incapacity

All of these examples display extreme excellence by arms of the U.S. state — the intelligence services, the military, the Federal Reserve, disaster relief and prevention agencies, scientific research agencies, BARDA, and even Congress. So how, then, do we juxtapose these successes with the massive state failures of the Iraq War, the slow recovery from the Great Recession, failure to suppress Covid, and excessive infrastructure costs?

The easy answer is that the U.S. government has pockets of competence and pockets of incompetence. Perhaps the Fed and the military are good at their jobs, while the CDC and the FDA are incompetent. And I won’t deny there’s a bit of truth there — at this point, pretty much everyone agrees that the CDC is deeply broken, and efforts to fix it have so far been unsuccessful. There are specific pockets of low state capacity that need addressing.

But by and large, America’s state failures look like something other than a decaying, incompetent government. The easiest way to see this is to observe how the same U.S. institution that fails in one crisis can succeed wildly in the next. Congress failed to pass enough stimulus to jog the U.S. out of its economic slump in 2010-12, but it succeeded in preventing a similar slump from Covid. The intelligence services whiffed on the Iraq WMD intel and yet called the Russia invasion exactly right.

There’s something else going on here, and it comes down to poor leadership and social division.

The reason we went to war in Iraq on flimsy intel was because George Bush wanted to. The reason we had a lackadaisical response to Hurricane Katrina was because Bush was a complacent and incompetent President. These were failures of leadership — but that doesn’t say much about the underlying system. Put incompetent people in charge, and any system will look broken.

Many of our other government failures are a result of our own choices. We fell behind in vaccination because a fraction of the country decided to embrace the antivax movement, first as a political move to support Trump, and then, after Trump came out in favor of vaccines, as a pure conspiracy theory and rejection of the mainstream media. We failed to do adequate stimulus in the Great Recession because the Tea Party Congress was opposed to it on ideological grounds. We failed to suppress Covid because many Americans were simply unwilling to accept the lifestyle changes necessary to lock the country down, and others refused to wear masks. And our infrastructure costs are high in large part because NIMBYs want to preserve their neighborhoods from development, and use things like environmental review and other political tools to make it hard to build roads and trains. And Congress actually gets a lot of bipartisan stuff done when no one is looking.

Does the difference between social division and government incompetence matter? Yes, very much so, because they require different remedies. If social division is the fundamental cause of government failures, restructuring of our institutions won’t fix things, because we won’t be able to agree one what we want those institutions to do. Even supposedly independent institutions like the Fed will only be able to preserve their relative autonomy for a while before they too are consumed by politics.

Of course, over time, social division can lead to low state capacity. A country that doesn’t build enough trains because NIMBYs don’t want poor people riding the trains to their neighborhood will eventually forget how to build trains cheaply. So we can’t count on American institutions to be preserved, ready to use, in 50 or 100 years when our social divisions heal. We have to focus on finding common ground now, or else our unwillingness to do things may harden into long-term disability.

But for right now, I think we need to reexamine the narrative of low U.S. state capacity — or as I put it, of American decline. The U.S. has some pockets of incompetence, but it’s not the “sick man of the world”. Not yet.

You know I’m in unabashed patriot. I love working internationally. People are great. And I also dislike western chauvinism, But I spent 22 years in the military working with the greatest people that we have. The real reason why the Russian military sucks because they don’t have the same sort of professional and listed core that the United States has. It’s not technology. It’s not those damn generals you see on CNN or Fox News. Those guys are over fucking rated. It’s 25 year old kids named Paul, supervising 19 and 18 year old kids name Susan and Jim, while they fix multi million dollar aircraft and perform in ways that would blow your mind.

But it’s not just that. Now I spent 2/3 of the year traveling all over north in South America. But mainly in the United States. I Watch blue-collar workers come together from all over the country, I watch them disassemble, inspect, and repair giant gas turbines, so that you can charge your iPhone. This working class magic is repeated at water plants, nuclear plants, bridges, at places like factories all over the country every day. We’re talking skilled manual labor, 12 hour shifts. Months away from their family.

So heck yeah, the United States has unused capacity. Yes we are a big dysfunctional family made up of dumb ass liberals with dumbass conservatives. And we muddle along. But at the end of the day, no one gets it done like us.

Ukraine will win.

Nice! One genuine missing capacity: we're not good at forcing outdated institutions to reform.

The CDC was designed for malaria alleviation, not pandemic prevention, and so it does that badly. The FDA was designed to be suspicious of new Big Pharma drugs, not helpful in nonprofit investigations of existing generics, and so it does that badly. California's PG&E was designed for power line maintenance in a low-wildfire environment, not our current hot one, and so it does that badly.

What does it take to fix a broken institution? The American armed forces were turned around by the Goldwater-Nichols reforms, but that happened only after serial disappointments in Vietnam, the Iran hostage rescue and Grenada.

Is there any way to fix our outdated institutions, short of waiting for a whole decade of disasters to convince people into actions?

It's not that our institutions are bad at their original jobs. It's that often enough, we need them now to do something new.