Two posts about de-dollarization

Your friendly neighborhood econ blogger counters the latest wave of hysteria.

Saudi Arabia recently announced that it’s open to settling trade (i.e., oil sales) in currencies other than the U.S. dollar. This has provoked a fair amount of consternation about the potential end of dollar dominance. This fear has been intensified by all the Bitcoin people who are screaming that the banking system is going to collapse and that this is going to spell the end of the U.S. dollar.

In fact, people shouldn’t be concerned at all. I’ve written two posts — one last year and one this February — explaining why A) de-dollarization is extremely unlikely to happen anytime soon, and B) some degree of diversification away from the dollar would actually be good for the United States. Both posts were paywalled, but I decided to unpaywall them, so that everyone can enjoy the peace of mind of not having to worry about the death of the dollar. So here you go!

Don’t worry about de-dollarization

A number of financial pundits are publicly worrying that the sanctions on Russia will lead to a post-dollar world. The basic idea here is that with Russia essentially cut off from financial transactions with the West, it will either turn toward deeper financial integration with China or toward the use of trans-national commodity currencies like gold and Bitcoin. And if that movement leads other countries to follow, then either the yuan, gold, or Bitcoin might become the global currency, and the U.S. might eventually find itself financially isolated instead of Russia. For example, over at the Financial Times, Rana Foroohar writes:

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine [will result in] a quickening of the shift to a bipolar global financial system — one based on the dollar, the other on the renminbi…[T]his supports China’s long-term goal of building a post-dollarised world, in which Russia would be one of many vassal states settling all transactions in renminbi…[T]he Chinese hope to use trade and the petropolitics of the moment to increase the renminbi’s share of global foreign exchange…Beijing is slowly diversifying its foreign exchange reserves, as well as buying up a lot of gold. This can be seen as a kind of hedge on a post-dollar word [sic].

Bitcoin boosters, meanwhile, naturally think the new global currency will be BTC.

To be blunt, this is unlikely to happen. Neither the Chinese RMB, gold, or Bitcoin is prepared to play anything like the role that the dollar currently plays in the global financial system. I’m not being contrarian by saying that, either — most of the top economists surveyed by Chicago Booth’s IGM Forum don’t think a shift away from the dollar is likely.

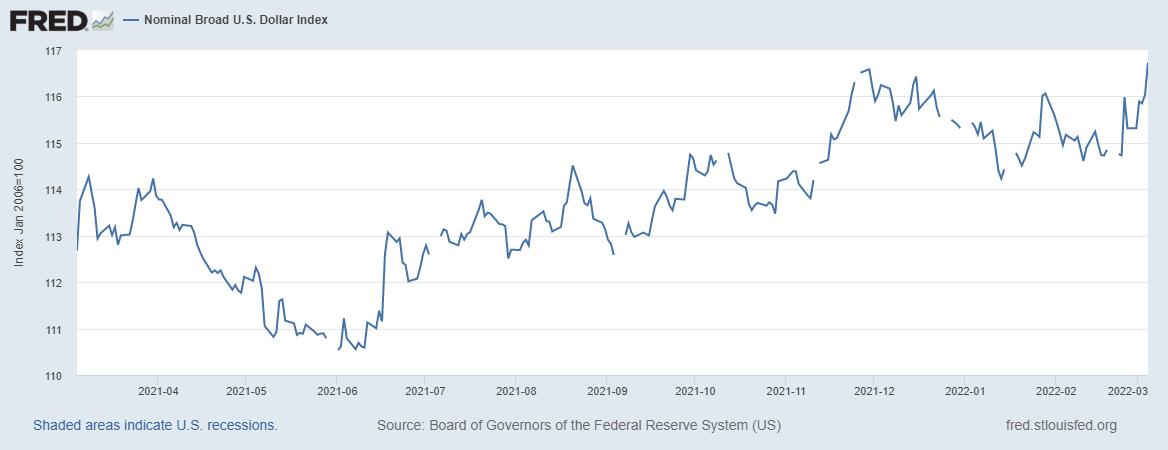

And markets seem to be even less concerned. The U.S. dollar’s value relative to the currencies of its trading partners actually rose after the sanctions, suggesting that confidence in the dollar is unshaken:

But although I may not be taking a bold contrarian stance here, it’s still worth it to explain why de-dollarization is highly unlikely to happen as a result of these sanctions (and why it’s also not as terrifying a prospect as people think).

Before I explain that, by the way, I should say that I do have some qualms about the way sanctions have been employed in this conflict. I think that wholesale destruction of a country’s economy is not generally an effective way of pressuring a repressive or aggressive regime to change its behavior, as Iran, North Korea, Cuba, and many other cases have clearly shown. I think sanctions should be focused on weakening a country’s military machine, not on impoverishing its populace — otherwise, by enraging the people against an external enemy, sanctions risk entrenching the very regimes they seek to weaken. I also do worry that there could be a slippery slope, in which ultra-harsh sanctions of the kind being used against Russia eventually get deployed in conflicts where the morality is not nearly so cut-and-dry.

So there are risks to these sanctions, I think. But de-dollarization is not one of them — at least, not in the current conflict. The first reason this is true is that the kind of financial shift people are worrying about would have to mean not just abandonment of the dollar, but also abandonment of the second most important international currency — the euro — at the same time.

De-dollarization would really mean de-dollar-and-euro-ization

The first thing to note about the financial sanctions on Russia is that they’re mostly about making it harder to use euros, not dollars. As of June 2020, Russia’s foreign exchange reserves were:

30% euros

22% dollars

23% gold

12% yuan

So when Western banks blocked the Russian central bank from making transactions, this was more about euros than dollars. And even more importantly, Russia traditionally imported a lot more from Europe than it did from the U.S.:

Remember, to import from a country, you need that country’s currency — American businesses get paid in dollars, eurozone businesses get paid in euros. So Russia had a lot more need for euros than it did for dollars. The current sanctions are therefore going to impact euros even more than dollars.

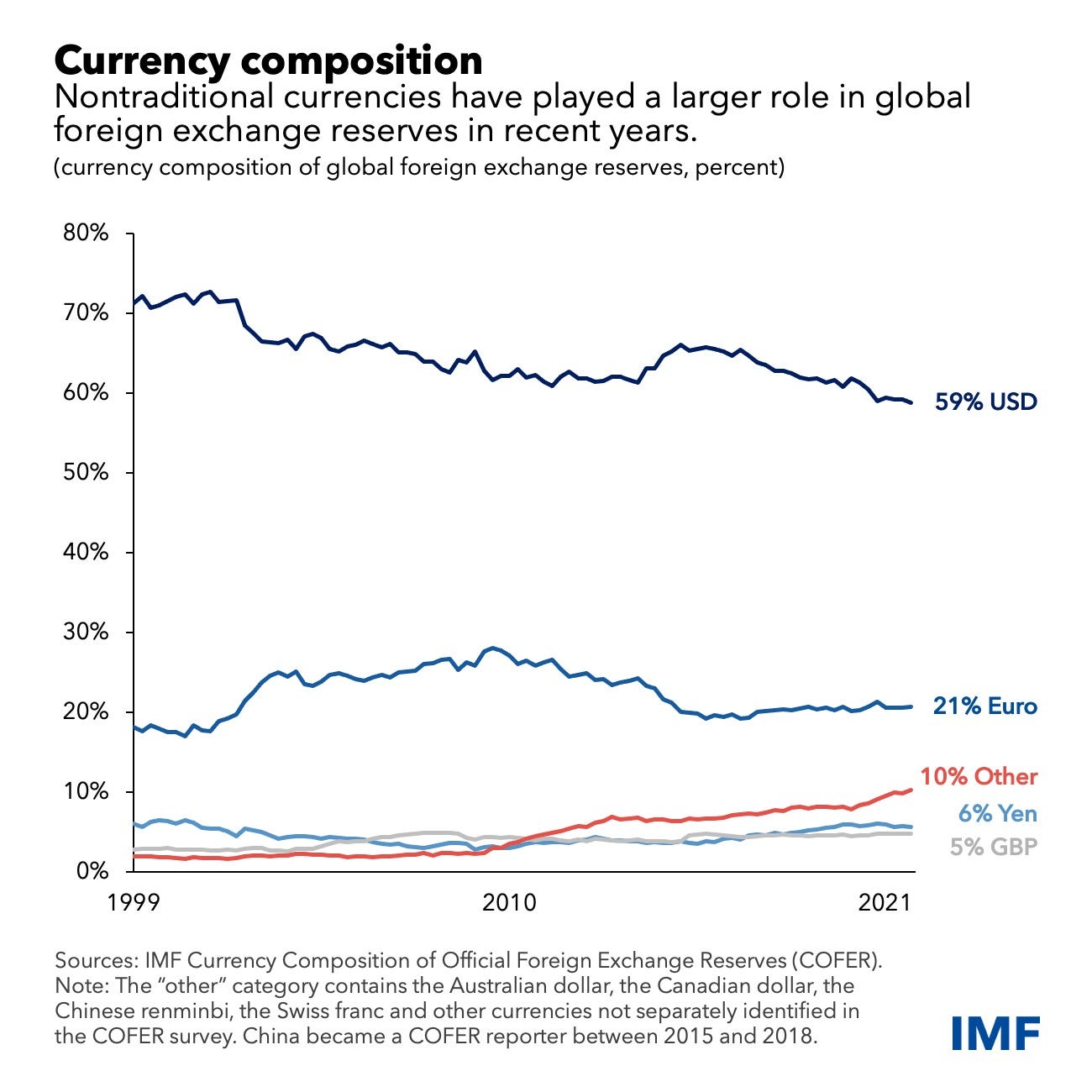

And remember that together, the dollar, the euro, and the currencies of other countries participating in the sanctions effort against Russia overwhelmingly dominate the composition of international reserves:

The yuan (RMB) is miniscule. (Gold isn’t included here but I’ll get to that in a bit.)

So to shift the financial system away from the currencies of the bloc of nations now putting sanctions on Russia would be an absolutely monumental undertaking. And none of the candidates to replace the current system really make sense.

Why the yuan isn’t ready to replace the dollar

The best alternative to replace the dollar would be the Chinese RMB (yuan). China represents around 18% of the world economy, and about 15% of world exports, so countries have plenty of reason to use the yuan. China is also a high-tech country with well-developed systems for banking and payments, so it would have no trouble handling the technical aspects of making the yuan the global reserve currency.

There’s just one problem: Capital controls. China has a lot of rules that make it very very hard to sell yuan for foreign currencies. And it’s not just about the current rules — there’s also a general awareness that if capital ever tries to leave China in any significant amount, the government will impose a bunch of new rules in order to stop it. This was vividly demonstrated in 2015-16, when a stock market crash caused a massive capital flight from China, but the government stanched the outflows by tightening up capital controls significantly.

Why does China make it so hard to get money out of China? One big reason is that this is necessary in order for China to control the value of the RMB. When capital flows out of China, it puts downward pressure on the currency, which makes it harder for Chinese companies to afford inputs and for Chinese consumers to afford imports. But when capital flows into China, it raises the value of the yuan, which makes it harder for Chinese exporters to sell goods overseas — since China traditionally has a mercantilist economic policy, this is something it wants to avoid.

So by becoming the international reserve currency, China would give up its control over the value of its currency, exposing it to both unwanted appreciations and unwanted depreciations.

Now, it’s possible that China will change its attitude here, as the U.S. changed our attitude toward international finance around the time of the world wars. The country’s leaders could decide to be less mercantilist and less control-freaky about their finances, in exchange for global leadership. Would it then be possible that countries like India and other emerging markets might migrate into a yuan bloc?

Unlikely. Because now that the U.S. and Europe have shown the power of financial sanctions, there is precisely a 0% chance that China would avoid using this weapon if it could. Whatever the West is willing to do in order to punish its adversaries, China would definitely be willing to do.

Implicit in the idea that sanctions would drive the world to join a China-centric financial bloc is the notion that China would somehow be a more benevolent financial hegemon, less likely to wield its power to punish nations for doing things it doesn’t like. And that notion is complete, pure, grade-A nonsense. Remember, China is the nation that just threatened to retaliate against Czech companies simply because a Czech politician paid a visit to Taiwan.

Joining a China-centric financial bloc will not save countries from the threat of economic coercion — it will vastly increase that threat. So don’t expect to see countries join such a bloc unless they’ve already been forcibly exiled by the West.

Why gold isn’t ready to replace the dollar

OK, so let’s talk about other possible substitutes for the dollar-euro. You’ll notice that gold isn’t included in the IMF’s chart of forex reserves above. In fact, gold is still a significant reserve asset, representing a little less than 15% of the total as of last year.

BUT, guess who holds most of that gold. Yep, it’s the “advanced” economies, i.e. the European and Asian countries putting the sanctions on Russia.

The U.S. itself is by far the biggest holder. (In fact, this fact is one thing that helped the world transition from a gold standard to a dollar standard after the world wars — for a while, those two things weren’t even that different.)

Of course, this doesn’t preclude the switch to a global gold standard, since most of the gold in the world is in private hands. But since gold can’t easily be carted around (this isn’t Dungeons & Dragons), this means that gold-based payments — whether the transfer of ownership rights over gold, or payments in some asset whose value is linked to gold — have to be handled electronically. And that means banks.

And who controls banks? National governments. The U.S. doesn’t have to own gold itself in order to tell Chase and Wells Fargo and Citibank how to handle gold-based payments. It can just do that. And China can do the same to its own banks, and Germany to its own banks, and so on. Which means that using gold for international payments isn’t really a way of immunizing yourself against the kind of sanctions deployed against Russia.

What we could see is a shift toward countries holding gold reserves, as a way of hedging against the possibility that the West might hit them with sanctions. In fact, Russia did this after 2014, and some other countries might do it too. But as I’ll explain later, this wouldn’t be such a bad thing.

But first, Bitcoin.

Why Bitcoin isn’t ready to replace the dollar

Bitcoin boosters frequently claim that Bitcoin will replace the dollar. But this will not happen.

First, let’s point out that people don’t expect anything like this to happen. When Russia attacked Ukraine, there was no surge in the price of Bitcoin:

…But there WAS a surge in the price of gold. People still regard gold as a safe haven against geopolitical instability, but they do not yet regard Bitcoin as a safe haven.

One possible reason is Bitcoin’s dependence on the global internet. Yes, you don’t technically need the internet to trade Bitcoin, but as the “bit” in the name implies, it makes it much much easier. If the global financial system carves itself into militarized blocs, the wide-open internet that allows Bitcoin to be easily traded across international borders will likely be far more restricted. Global war might even make the internet go down across much of the world.

But even with the internet up, Bitcoin is incredibly hard to use for transactions. Transaction fees are pretty high even for the small transactions currently being done. But the Bitcoin network simply can’t handle transactions of the size and frequency needed to support the global financial system (this scalability problem is so well-known that it has its own Wikipedia page). Bitcoiners have promised to create a network called Lightning that will solve these problems, but this has proven very difficult to create so far.

There’s also the fact that national governments do have a significant amount of control over Bitcoin. The FBI showed that Bitcoin transactions are traceable, meaning that governments can punish people for making such transactions if they want to. And as China has demonstrated, it’s possible for countries to ban Bitcoin mining pretty effectively.

It’s possible that blockchain technology advances to the point where it’s both immune to national control and able to handle huge and frequent transactions cheaply. So far, it’s not there, and Bitcoin seems unlikely to be the cryptocurrency that gets there first, if any ever does.

So, no Bitcoin standard to replace the dollar-euro.

A little bit of de-dollarization would be a good thing

In this post I’ve argued that dollar-euro financial hegemony won’t be replaced as a result of these sanctions, simply because none of the alternatives is ready to replace it. But it is possible that sanctions might cause a modest shift in the composition of reserve assets held by central banks around the world. Maybe countries won’t shift to yuan-based or gold-based systems, but they might hold a bit more yuan and gold, just as a hedge.

In fact, this would be a good thing.

The fact that countries hold lots of dollar reserves means that there is a large international demand for dollars beyond simply the need to buy U.S.-made goods. Countries like China and Japan and Saudi Arabia park their money in U.S. assets for a number of reasons. One is to insure themselves against a big drop in their currencies — if their currency falls suddenly, they can sell dollar reserves to prop it up. Another reason is because America is a huge and open consumer economy, and countries can sell Americans lots of export goods by keeping their currencies cheap against the dollar — this requires accumulating dollar reserves.

This creates some benefits for America — the so-called “exorbitant privilege”. Holding dollar assets means lending money to American borrowers, so the fact that countries want to hold a bunch of dollar assets means that Americans get to borrow cheaply. This could include American companies looking to borrow money in order to do stock buybacks (or invest in business expansion), American consumers looking to get cheap mortgage loans, or American banks looking to borrow cheaply in order to make more loans.

Great, right? Except this also makes American exports much more expensive overseas, because higher demand for dollars makes the dollar more expensive. This “strong dollar” is one reason for the U.S.’ large and persistent trade deficit:

This pushes the U.S. away from export industries like manufacturing, and toward industries that benefit from cheap borrowing — finance, real estate, etc. In other words, the strong dollar is probably one culprit in the financialization of the U.S. economy.

Over-reliance on dollar reserves also creates risks for other countries. If the U.S. has much higher inflation than the rest of the world (as has happened in the last year or so), this will erode the value of central banks’ reserves (since most of the dollar reserves are bonds with fixed nominal interest rates, whose value inflation destroys). Also, as I argued in Bloomberg, a period of severe political instability in America could cause global financial chaos.

Thus, a modest shift away from the dollar as the global reserve currency would be a good thing — it would help reduce global imbalances, as well as the imbalances within the U.S. economy itself. And it would make the global financial system more robust.

Perhaps now that Europe is looking more vigorous and united as a response to Russian aggression, the euro can become more important as a second global reserve currency. But really, China needs to step it up here. They’re now a very significant portion of the world economy, and yet because of their capital controls they’re not doing their part to support the stability of the global financial system. A moderate international diversification from dollars into yuan would be a good thing, even if — for the reasons stated above — I think it’s pretty unlikely to happen anytime soon.

So to sum up, don’t worry that sanctions will spell the end of the dollar’s role in global finance. This is highly unlikely to happen. And if somehow there is a modest shift away from the dollar, especially toward the yuan, it could help correct some of the system’s current flaws — to the benefit of basically everyone involved.

“Threats to the dollar” are just scare stories

One of the most common questions people ask me is some variant of: “Is the U.S. dollar going to lose its dominance?” Variations on this include:

Will the BRICS overthrow the dollar?

Will the end of the petrodollar spell the end of dollar dominance?

Will alternative currencies replace the dollar?

What if countries diversify their reserves away from the dollar?

The answers to these questions are: 1) No, 2) No, 3) No, and 4) That would be a good thing.

Lots of people seem to think of international finance as a sort of power struggle — whoever’s currency is dominant, or strong, wins. Thus, when Americans read stories alleging that some new threat is about to overthrow the dollar, they worry that this spells the decline of the U.S. as a country, or at least of U.S. economic strength.

In fact, this is just not how things work. The U.S. does derive some benefits from the fact that countries tend to hold a lot of dollar-denominated reserves, but it also pays some very important costs. It’s likely that both the U.S. and overall global stability would benefit from a more balanced international financial system. But that having been said, it’s also the case that most of the “threats to the dollar” that get discussed in the financial press are vastly overhyped.

So let’s talk about each of these scare stories, and why each of them is highly implausible. And then at the end I’ll talk a bit about why the U.S. should want to see other countries diversify their reserves away from the dollar to some degree.

The BRICS are not really a thing

In 2001, a Goldman Sachs economist named Terence James O'Neill, Baron O'Neill of Gatley — known to most of us as “Jim” — created one of the most annoying economic memes of all time, when he grouped Brazil, Russia, India and China into a grouping called the BRICs. Later someone decided that Africa should be represented on this list, and so South Africa was added to make the BRICs into the BRICS.

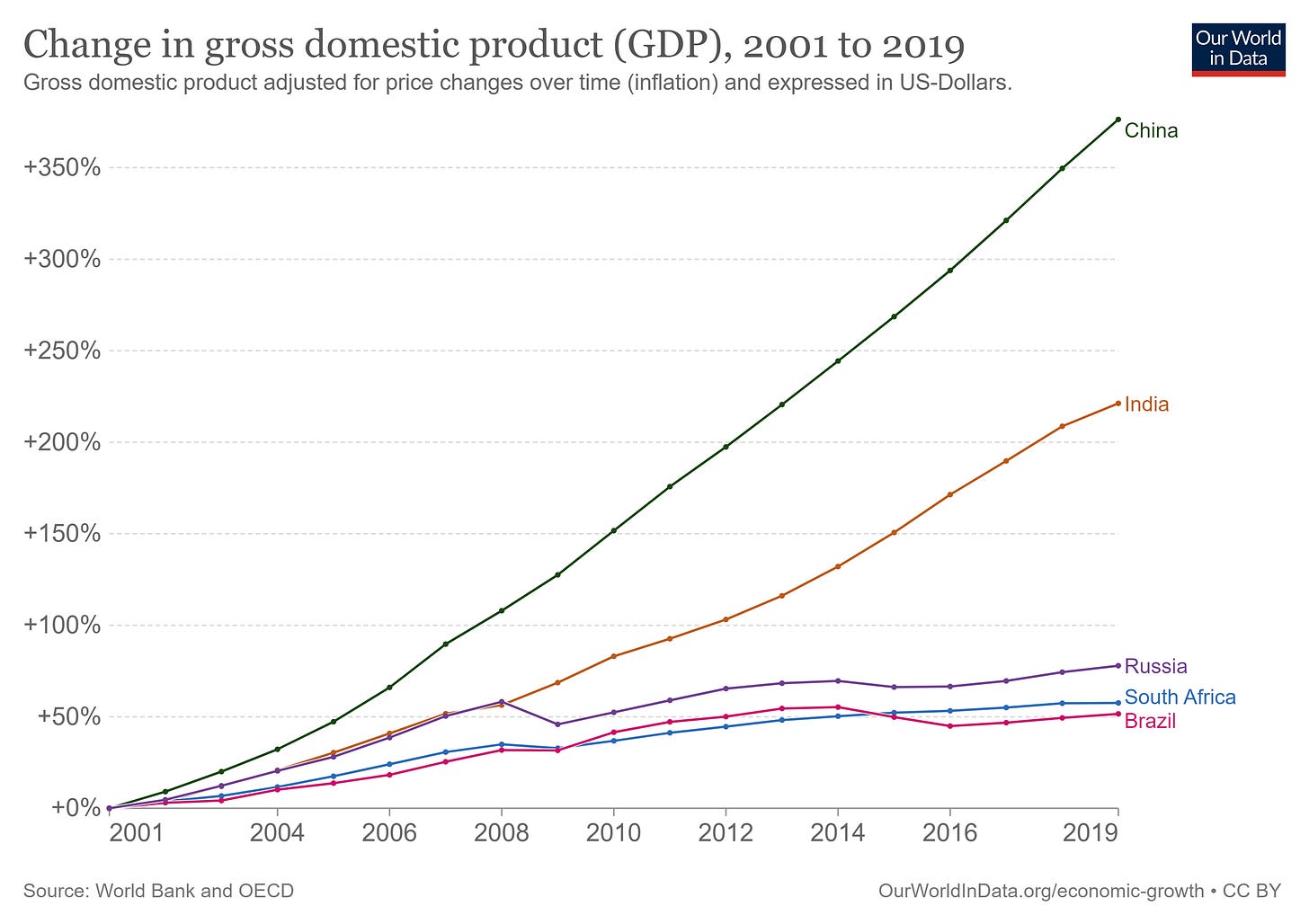

Essentially, this was a group of large countries that Jim O’Neill expected to grow a lot over the coming decades. That didn’t exactly pan out; China and India fulfilled their promise, but the others merely puttered along.

Unfortunately, however, some of the leaders of these countries decided that BRICS might mean more than just an investment thesis; they decided that it was going to be a power bloc, a kind of new economic non-aligned movement that would wrest control of global economic institutions away from the U.S., Europe, and their allies. In 2009 they started meeting regularly and trying to think about how to create their own economic institutions — a New Development Bank to compete with the World Bank, a Contingent Reserve Arrangement to lend each other money in times of currency crisis (something the IMF usually does), a system of submarine fiber-optic cables, and so on.

This, too, did not end up working out. The New Development Bank has disbursed almost no loan money at all, causing Jim O’Neill to declare it a disappointment. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the NDB cut ties with it. The Contingent Reserve Arrangement has done basically nothing, and the BRICS Cable never happened.

Given this history, you should be extremely skeptical when you read stories like this one:

Russia is ready to develop a new global reserve currency alongside China and other BRICS nations, in a potential challenge to the dominance of the US dollar.

President Vladimir Putin signaled the new reserve currency would be based on a basket of currencies from the group's members: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

"The matter of creating the international reserve currency based on the basket of currencies of our countries is under review," Putin told the BRICS Business Forum on Wednesday[.]

This is incredibly unlikely to happen. First of all, it would require Brazil, India, China, and South Africa to deepen their cooperation and solidarity with Russia, at a time when all of them appear to be edging away. If the BRICS’ own development bank cut ties after Putin’s invasion, what’s the likelihood that India, China, etc. will commit themselves to a joint reserve currency with Russia? Seems very low.

Such a joint reserve currency would also require India to tie its financial future to China. Since China is by far the biggest economy of the bunch, the yuan would dominate any BRICS reserve currency in practice, meaning that capital inflows and outflows into the rupee via the new reserve currency would be determined by the policies of the People’s Bank of China. Given that India generally has quite high tensions with China — Modi has banned many Chinese tech companies, and used the 2021 BRICS summit to raise questions about the origins of COVID-19 — this seems unlikely.

Finally, a joint reserve currency gains China little over simply opening up its own capital account and allowing the yuan to be a major reserve currency. China could certainly do this at any time, but it would then sacrifice its ability to regulate capital inflows and outflows and control its exchange rate. China’s leaders are notoriously afraid of capital inflows that would push up the value of the yuan and make Chinese exports uncompetitive, and they’ve also acted in dramatic fashion to stop capital outflows from causing a currency crash. So I highly doubt China is going to want the yuan to be like the dollar any time soon.

In other words, the notion of BRICS creating a reserve currency to replace the dollar is vaporware, cooked up by Putin to try to get other countries on his side in his struggle against Europe.

Petrodollars are not important

When hearing scary stories about the overthrow of the dollar, you may have heard the word “petrodollar”. The finance blog world is peppered with stories with titles like “The End of the Petrodollar?”, “Why the End of the Petrodollar Spells Trouble for the US Regime”, and “Preparing for the Collapse of the Petrodollar System, part 1”.

The first thing to understand is that there is no currency called a “petrodollar”. Petrodollars are just dollars that are used to pay for oil. What happens is this:

Oil exporters like Saudi Arabia sell oil for dollars.

The oil exporters then use those dollars to buy assets like U.S. Treasury bonds.

When people talk about the “end of the petrodollar”, they mean one or both of the following:

Oil exporters selling oil for some other currency, such as yuan, and/or

Oil exporters investing their earnings in other countries’ assets instead of Treasuries.

Either of those things would reduce global demand for dollars. If oil exporters demanded to be paid in yuan instead of dollars, then countries would need to buy yuan instead of dollars in order to pay the oil exporters. And if oil exporters still got paid in dollars but decided to invest their earnings in non-dollar assets, they would have to sell the dollars for other currencies (e.g. yuan) in order to do so; this would also reduce the demand for dollars.

First of all, oil exporters are unlikely to switch to the yuan, either in terms of payments or as a place to stash their reserves, for reasons discussed above. It would require China to allow capital inflows and outflows, which it doesn’t want to do.

But more importantly, petrodollars are just not a big deal in terms of dollar demand. Saudi Arabia’s total forex reserves are only $471 billion, a bit smaller than Taiwan’s. Russia, due to financial sanctions, is no longer a factor here.

As for the dollar demand needed to actually make oil purchases, that’s not a big deal either. OPEC’s whole net oil export revenue is about $397 billion per year, and the number of dollars countries need to keep handy in order to buy that oil is going to be less than that.

In other words, petrodollars are just not a huge deal. People who claim that the petrodollar system provides the “backing” for the dollar, as some kind of new oil-based gold standard, don’t really know what they’re talking about. You should not listen to them. Instead you should read this Investopedia article by James Chen, explaining, once again, that the dollar does not depend on petrodollars. The bottom line here is that oil is not the reason people hold dollars.

Alternative currencies are not happening

A third “threat to the dollar” that you sometimes see getting discussed in the press is the rise of alternative currencies. These include:

Bitcoin

stablecoins

gold

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs)

various other things

For example, I see scattered reports that Russia and Iran creating a gold-backed stablecoin for use in trade between the two countries. If throwing “Russia and Iran”, “gold”, and “stablecoin” into a story sounds like Mad Libs, well, that’s because it is. Russia and Iran have no reason to use blockchains to carry out trade between their countries, and if they did, they could just use Tether. A medium of exchange between Russia and Iran does not need to be “backed” by anything, including gold — it’s just a system for exchanging goods and services between the two. And for this hypothetical gold-backed stablecoin to displace the dollar in any way, a bunch of countries would have to buy the coin, which they would have little reason to do, since if they want to trade with or invest in Russia and Iran they can just buy rubles and rials. In other words, “Russia and Iran create a gold-backed stablecoin” is just another case of Putin throwing nonsense at the wall and seeing what sticks.

Equally as ludicrous is the idea that a proposal for a common currency between Brazil and Argentina would represent any sort of challenge to the dollar. First of all, why any country in its right mind would want to tie its monetary policy to Argentina’s, I don’t know. But more importantly, this currency would be an extremely minor player compared to things like the euro, the yen, the pound, and the won, which are already alternatives to the dollar.

As for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), they’re not actually new currencies, just payments apps — state-sponsored versions of Venmo or Zelle. I explained in an earlier post why they’re not a big deal:

Bitcoin is not going to replace the dollar; even ignoring all the problems with energy usage and transaction difficulty, no one is going to choose a reserve currency that people don’t even use to buy pizza and beer.

As for gold, it’s something that countries can (and do) use to diversify their reserve holdings. So in that sense, it is a minor “threat to the dollar”. But in fact, reserve diversification is not a threat at all; it’s a good thing.

Reserve diversification is good for the U.S.

This brings us to the final “threat to the dollar” — reserve diversification. Since the turn of the century, there has been a downward drift in the percent of global foreign exchange reserves held in dollars:

Countries’ central banks also hold gold reserves, which aren’t pictured here. China, Russia, and Turkey have built sizeable gold holdings over the last two decades, but most of the gold held by central banks is still held by the U.S. and Europe.

A recent IMF report shows that recent diversification out of the dollar is being driven largely by diversification into other currencies — a little bit into the yuan, but largely into currencies like Canadian and Australian dollars, South Korean won, Swiss francs, etc. This is highly unlikely to spell the death of the dollar as a major reserve currency, or even as the major reserve currency. But it does erode dollar “dominance” of international finance.

And guess what? That’s a good thing.

We use words like “strong” and “dominant” to describe an expensive dollar that’s in high demand. But those words give the phenomenon a positive connotation that it doesn’t deserve — they create the false impression that a “strong” and “dominant” dollar means a strong U.S. economy and dominant U.S. power in the world. Neither one is true.

In a post a year ago, I explained why a “strong” dollar weakens our export industries (including manufacturing), and pushes our country toward financialization:

[A strong dollar] creates some benefits for America — the so-called “exorbitant privilege”. Holding dollar assets means lending money to American borrowers, so the fact that countries want to hold a bunch of dollar assets means that Americans get to borrow cheaply. This could include American companies looking to borrow money in order to do stock buybacks (or invest in business expansion), American consumers looking to get cheap mortgage loans, or American banks looking to borrow cheaply in order to make more loans.

Great, right? Except this also makes American exports much more expensive overseas, because higher demand for dollars makes the dollar more expensive. This “strong dollar” is one reason for the U.S.’ large and persistent trade deficit…This pushes the U.S. away from export industries like manufacturing, and toward industries that benefit from cheap borrowing — finance, real estate, etc. In other words, the strong dollar is probably one culprit in the financialization of the U.S. economy.

As for U.S. power, it’s true that the ubiquity of dollar-based payment systems allows the U.S. to threaten financial sanctions like the ones it recently imposed on Russia. That is a form of power, though it’s not America’s primary or most important weapon. But note that the dollar, euro, and yen together are far more dominant than the dollar alone. And note that most of the currencies that central banks are diversifying into are also U.S. allies — Canada, Australia, South Korea, and so on.

There is only one currency in the world that could ever really threaten the combined financial power of the U.S. and its allies, and that is the yuan. If China ever decided to float its currency and open its capital account, then yes, the currency of the world’s biggest manufacturer and biggest exporter might indeed supplant the dollar as the world’s reserve currency, and yuan-based payment systems might indeed replace dollar-based payment systems across the globe. It might be similar to the transition from the British pound to the U.S. dollar a century ago. Or failing that, at least it might result in a bifurcated financial system, with China as a fierce peer competitor to the U.S. and Europe for control of global payments systems, capital flows, and financial leverage.

But given China’s unwillingness to give up control over its currency’s value against the dollar and euro, and over capital inflows and outflows, this one real challenge to the dollar doesn’t seem likely to materialize soon. Thus, all of the scare stories you hear are wrong, and the mild diversification out of the dollar that you read about in the news is a good thing for the U.S.

Great content. But the BRICS ARE Killing my people in my village back in Nigeria. China and Russia supply arms in exchange for gold to bandits and terrorists while my people die in the hands of these criminals.