Some people are going to see this post as premature. Though the Ukrainians have turned the tide against the Russian invaders, the outcome is still in doubt, and much destruction still lies in the future. But at this point it seems likely that a country called Ukraine will survive this conflict, with most or all of the territory it possessed before Putin invaded. So it’s time to start thinking about reconstruction and growth after the war’s end.

Certainly after the shooting stops, the first order of business — and the task of several years — will be to rebuild the parts of the country torn down by Putin’s assault. Cities like Mariupol and Kharkiv are being reduced to rubble, much of the country’s infrastructure is being torn up, and about a quarter of the entire population has been displaced. It took Japan and Germany both slightly over a decade after the end of WW2 to reach the level of income they had enjoyed before the war. Ukraine hopefully won’t be in quite such bad shape after this conflict, but this isn’t going to be the kind of thing a country bounces back from in 1 or 2 years.

Ukrainians will work very hard to rebuild their country, but they’re going to need help. And given the U.S. and Europe’s copious military assistance, it seems likely that they’ll offer rebuilding assistance as well. In fact, the EU has just started setting up a postwar reconstruction fund, and the U.S. has already spent $13 billion helping the Ukrainians. Both the U.S. and EU leadership know that they can’t afford to have a weak, economically backward Ukraine as the first line of defense against a newly malevolent Russia, and the Ukrainians’ cause has resonated deeply with the U.S. and EU populations alike. So expect copious economic aid to flow for at least a decade.

But aid alone doesn’t build a country into an economic powerhouse. We Americans tend to think that the Marshall Plan was how Germany rebuilt its economy after WW2, but in fact this only provided a small initial kick — most of West Germany’s economic rise in the mid and late 20th century happened via its own investment and industrialization, helped by favorable trade treaties with allied countries. Ditto for Japan.

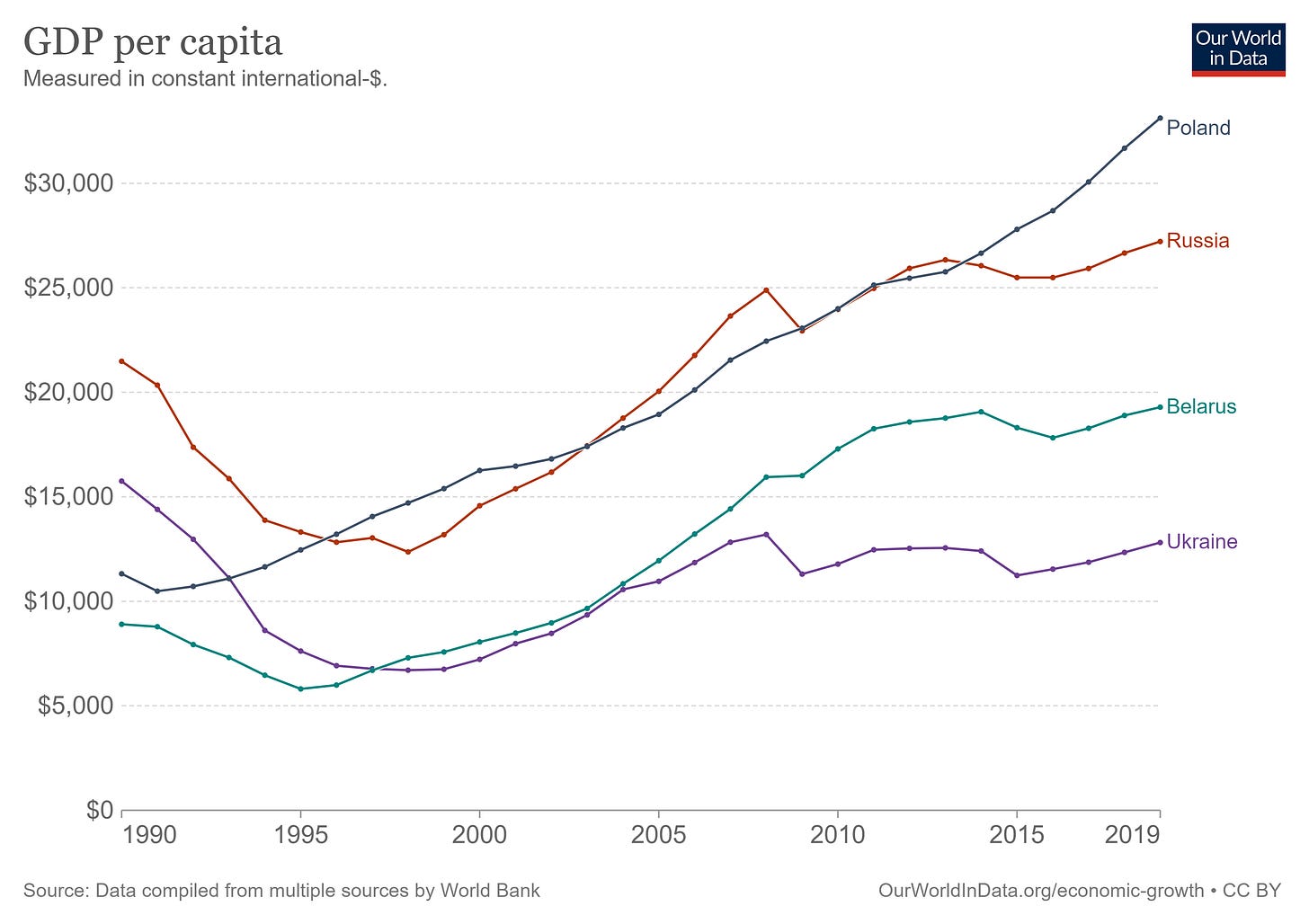

And Ukraine really needs to build itself into an economic powerhouse. Russia has four times Ukraine’s population; having a higher GDP than a sanctions-stricken postwar Russia would help Ukraine even up the balance of power a bit. Remember that before the war, Ukraine’s economy had languished for three decades, with living standards well below those of Poland, Russia, or even Belarus:

If Ukraine is going to be able to stand up to Russia for the rest of this century, it needs to reverse this situation. In a post before the war started, I offered a few thoughts on how to do that. The two main steps I recommended were A) reining in the political power of the oligarchs, and B) improving tax collection. Those are obviously still high priorities. But an industrial policy oriented toward rapid growth will have to go far beyond those basic steps.

First let’s talk about a couple of economic activities that Ukraine is good at, and which it needs to continue to be good at, but which will probably not provide the kind of broad-based advanced industrialization that the country needs.

Dutch Disease and defense manufacturing

One thing Ukraine does really well at is agriculture. Remember all those photos of Ukrainian farmers stealing Russian military vehicles? Well, when they’re not towing away armored trucks, they’re doing a damned good job of pumping out corn, wheat, and other foodstuffs. Ukraine isn’t known as Europe’s breadbasket for nothing:

But nations don’t get rich on agriculture alone. (Agricultural regions can be rich, but this is because they’re very sparsely populated; look at a map and compare the population density of Ukraine with that of Iowa to see what I mean.) As the research of Cesar Hidalgo and Ricardo Hausmann has shown, countries tend to get rich when they have complex economies that do a lot of different stuff; agriculture just isn’t that complicated.

And that’s fine; just do more than agriculture. The problem is that a country that exports a ton of crops always has to be on the lookout for Dutch Disease. Dutch Disease, in this context, is when commodity exports raise the value of a country’s currency, making it hard to export manufactured goods. (If you don’t already know, it works like this: People need Ukrainian hryvnia to buy Ukrainian crops; the demand for the hryvnia raises its value; an expensive hryvnia makes it expensive for countries to buy manufactured goods made in Ukraine.)

The way you combat Dutch Disease is to reduce the value of your currency. This makes imports more expensive, which can make people mad. But Ukraine is going to exit this war with a heck of a lot of national unity and spirit of shared sacrifice, so it’s likely that their populace will tolerate an undervalued currency in the name of economic growth. A harder sell will be European countries, who are probably not eager to run trade deficits with Ukraine. But they can probably be convinced to allow a cheap hryvnia for security’s sake.

A second thing that Ukraine is surprisingly good at is defense manufacturing. The country inherited much of Soviet defense manufacturing, and the industry still employs about 1 million people in a country of 44 million. There are plenty of examples of Ukrainian weaponry excellence — for example, though everyone knows about the Javelin and NLAW antitank weapons that the U.S. and Europe have given to Ukraine in large numbers, fewer know about the Stugna-P, a Ukrainian-made antitank system that has also performed well. Ukraine also has Yuzhmash, a rocket and missile manufacturer that can probably make better ballistic missiles than Russia’s, and Antonov, an aircraft company that made the world’s largest airplane before Russian invaders blew it up.

So that’s good — Ukraine is going to need to keep making a lot of high-quality advanced weaponry to defend itself from the Russian threat. But as Russia itself has shown, advanced defense manufacturing by itself doesn’t make an economy industrialized. Russia has Sukhoi and MiG, but this hasn’t stopped Russia’s economy from being largely “a gas station”, as the late John McCain colorfully put it. Meanwhile, U.S. naval shipbuilding capacity hasn’t done much to stop commercial shipbuilding from moving to South Korea and thence to China, while many big defense contractors like Lockheed Martin have been ultimately uncompetitive in private markets.

That doesn’t mean Ukraine should ignore its defense manufacturing industry, or agriculture. Both of those need to continue to be strong. But the country needs to maintain a parallel focus on building up private industry. And in order to figure out how to do that, one good idea is to look at similar countries that have managed the feat in the past. Two very useful examples for Ukraine are Poland and South Korea.

The Poland strategy

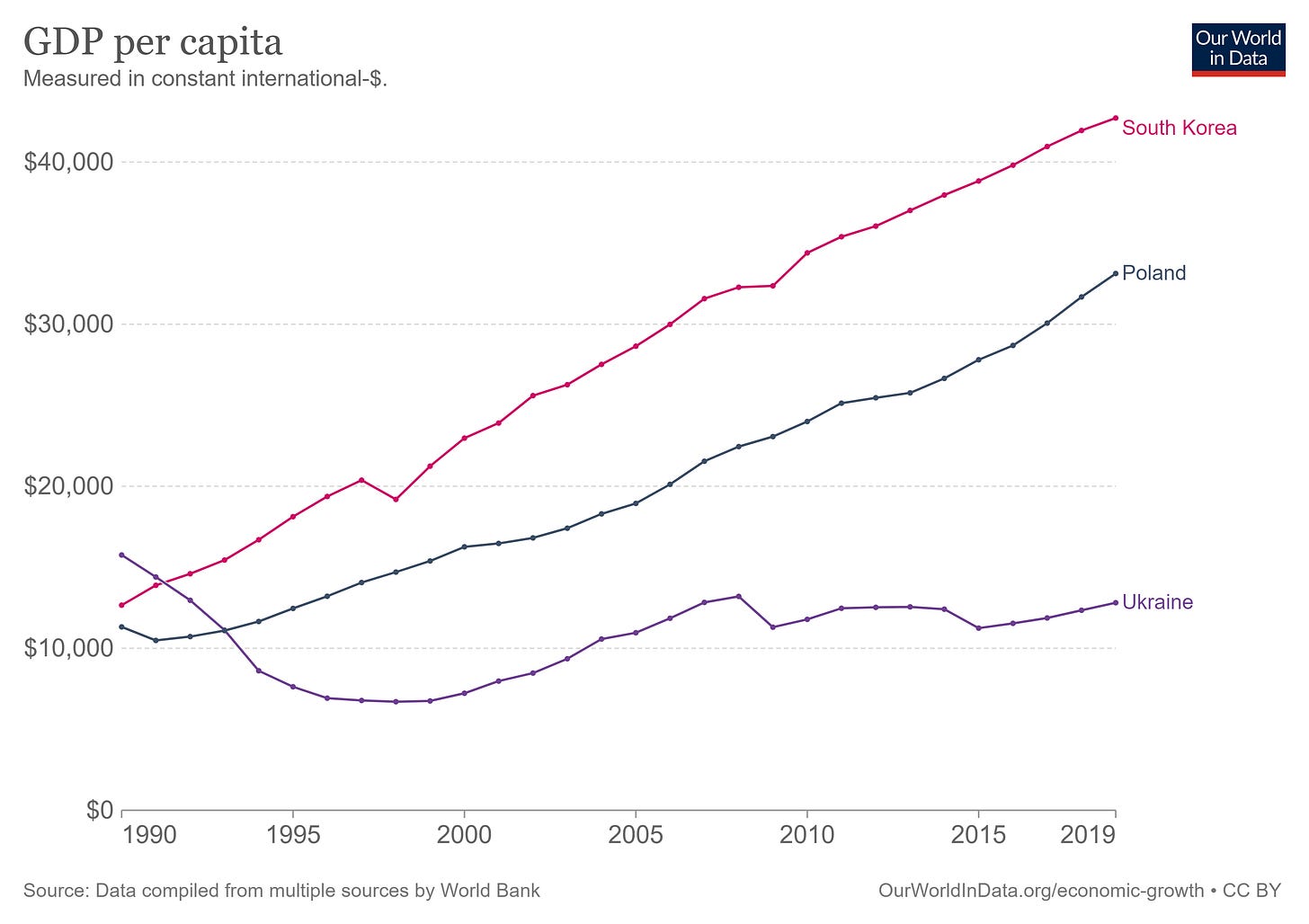

Believe it or not, when Ukraine gained its independence from the USSR in 1991, it was actually richer than either South Korea or Poland. Three decades later, however, South Korea had become a fully developed country, while Poland was on the cusp of being one:

Understanding just how this happened can help Ukraine replicate the feat.

Poland is perhaps the country most similar to Ukraine in terms of its geography and recent economic history. It emerged from the Cold War with a communist economy that went through a period of painful “shock therapy”. But unlike Ukraine, Poland started to grow rapidly in the 1990s, and hasn’t stopped yet. Why? One clue is to look at what Poland exports:

The basic answer here is “everything”. Poland sells a little bit of everything, which indicates a highly complex and diversified economy — exactly the kind of thing Hidalgo and Hausmann would recommend. But also notice the prominence of two industries: A) electronics, and B) cars and car parts.

In fact, if you look at any successful industrialization story, you’re going to see at least one of these two product categories be very prominent — and usually both. There are multiple reasons for this. One is that these are very complex and difficult-to-make products, so they require high technology in order to make; that increases value added and generates productivity spillovers for other industries. Another is that these are highly differentiated products, creating lots of scope for both specialization and branding, both of which tend to be quite lucrative. (As an added bonus, vehicles and electronics are both pretty useful for the military.)

So, to really industrialize, you’re going to want to make a lot of different stuff, but especially vehicles and electronics. How did Poland do that? Well, one very important ingredient was foreign direct investment. Poland is something of an FDI star — in 2020, it ranked fifth among all countries in “greenfield” FDI (i.e. new projects), behind Germany, China, the U.S., and the UK (all much larger than Poland). Poland’s FDI as a percent of GDP is about 2.9%, higher than China’s 1.4%. Most of this investment is from West Europe.

The most important country here is Germany. It’s the country’s largest trade partner and just about tied with the Netherlands as Poland’s largest source of FDI. European companies in general, and German companies in particular, have used Poland as a cheap high-productivity manufacturing platform.

Interestingly, some development experts, such as the economist Ha-Joon Chang, recommend against this strategy. Foreign companies, they argue, will refuse to fork over their best technologies to the countries they contract their manufacturing to, and will squelch competition from global brands. In Poland’s case, the first of these doesn’t really seem to have been a problem so far; Poland has managed to steadily absorb foreign technology and grow its total factor productivity. But as it nears the technological frontier, it will have to shift its model to emphasize research more.

Meanwhile, the second of the two concerns continues to nag — one would be hard-pressed to name a truly global Polish brand. So people who think about Poland’s future growth strategy, as it tries to make that final leap to fully developed status, often focus on growing Polish brands.

But I don’t think Ukraine really has to worry about these pitfalls for a while. Simply going from its prewar GDP level to Poland’s GDP level at that time would be a 2.6x increase. The strategy of taking in a bunch of FDI has its issues, but it’s fast, easy, and proven. (Update: Commenter DxS suggests that Ukraine could encourage FDI with a special economic zone, similar to what China used. That sounds like a great idea; I’d probably suggest Lviv, which is the big city farthest from possible Russian bombardment.)

The real question here is whether European countries are willing to invest. On one hand, there’s talk of fast-tracking Ukraine for EU membership after the war; even if this doesn’t happen, some kind of special trade arrangement is very likely. On the other hand, the risk of another Russian attack will loom large over any plans to put German or Italian care and electronics factories in Ukraine. If that puts a chill on FDI, then Ukraine should consider cribbing a bit from South Korea instead.

The South Korea strategy

When the Ukraine war finishes, Ukraine is probably going to be left in a situation similar to the one South Korea found itself in after the Korean War — facing an implacable, militaristic enemy on its border, with a war that could reignite at any time. That’s not necessarily a hopeless place to be; South Korea is probably the world’s most incredible development story. In the mid-1960s it began what would ultimately be one of the most sustained runs of rapid growth the world has ever seen.

Many credit the military dictator Park Chung-hee with igniting this transformation, though the rapid growth continued long after his assassination in 1979. If you want to read at length about this guy and how he did what he did, the best book to read is The Park Chung Hee Era:

How Asia Works, my favorite development book, devotes an entire section on how Park successfully encouraged indigenous car companies, electronics companies, and steel companies. Results for Park’s later Heavy and Chemical Industries initiative were also positive, though somewhat more mixed (it boosted growth but probably caused some misallocation of resources). There’s a lot of economic research you can read on this. Two good recent papers include Choi & Levchenko (2021) and Lane (2021) are my favorites; both find significant and lasting positive growth effects from Park’s industrial policies.

But South Korea’s strategy isn’t as simple as “pick winners, and be good at it”. As Joe Studwell notes in How Asia Works, Park spent a considerable amount of effort pushing business leaders to export more, occasionally even briefly jailing them if they wouldn’t accede to this demand. This wasn’t mercantilist — it wasn’t done in order to generate a trade surplus. In fact, one interesting thing about Korea’s industrialization is that it often ran a trade deficit, importing the capital goods it needed to fuel its growth machine.

Instead, Park encouraged exports in order to raise the country’s level of technology. Competing against foreign giants — Hyundai against Volkswagen and Toyota, for instance — would toughen Korean companies up, expose them to new ways of thinking, and force them to import foreign technologies (often by importing foreign employees) to match their competitors’ high product quality. Exporters that failed to compete with global rivals would have government support pulled. This approach is often called “export discipline”.

And Park also worked to make sure that important inputs of the vehicle and electronics industries — for example, steel — were in plentiful and cheap supply from domestic producers.

This sort of policy, focused on nurturing highly competitive national champions in high-tech industries, is difficult to pull off (Studwell contrasts Samsung’s success with the failure of Malaysia’s Proton). But when it works, it really works. Korean brands like Hyundai, Samsung, and LG are internationally known and respected, and these are some of the highest-tech companies in the world. As a result of building its own vehicle and electronics industries from scratch, South Korea has done even better than Poland has.

If Germany and the rest of Europe get cold feet about putting their factories in a country that’s subject to re-invasion at any time, then Ukraine will have little choice but to shoot for a South Korea style miracle. Fortunately, it will likely be helped in this quest by the willingness of friendly Western countries to open their markets to Ukrainian-made goods, just as they were willing to open up to Korean-made goods in the past. It’s a tried and true Cold War strategy.

So as soon as Ukrainian leaders get done blowing up Russian tanks, they should curl up with a nice book about Park Chung-hee. Ukraine will fortunately not be a military dictatorship, but their postwar national unity will hopefully allow them to achieve the same continuity and unity of purpose. Park’s habit of throwing businesspeople in jail for lackadaisical growth policy probably can’t be replicated with Ukraine’s oligarchs, but I’m sure they can find some other creative ways of focusing their industrial barons on importing technology and exporting high-value goods.

In any case, the models of Poland and South Korea seem like they provide the best examples for Ukraine to try to copy after the war. And indeed, Ukraine should invite advisors in from both countries. In this troubled age, democracies have to look out for each other’s economic interests as well as military ones.

Would Ukraine benefit from a Special Economic Zone centered on one of its cities, like China did adjacent to Hong Kong?

Creating a designated area and saying "export businesses and FDI especially welcome here" seems to help overcome both incumbent resistance to reforms (they can be isolated to a small area at first) and foreign investor nervousness (they can expect a critical mass of development-oriented services sooner if it's all happening in one area).

this is brilliant, thanks!