In 2014, I got a call from a reporter in Turkey. She wanted to talk about a blog post I had written, called “The Neo-Fisherite Rebellion”. In that post, I talked about a few macroeconomists who were toying with the idea that low interest rates — which most people think encourage higher inflation — might actually reduce inflation. She told me she was interested because Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his administration had been advancing this idea, and were looking for support from economists. When I told her that Neo-Fisherism is probably wrong, and that low rates probably do encourage inflation after all, she seemed disappointed.

Now the whole country has reason to be disappointed. Again and again throughout his tenure in office — first as Prime Minster since 2003 and now as President since 2014 — Erdogan has relentlessly campaigned for low interest rates. When the central bank would raise rates (e.g. to stem the currency crisis in 2018), Erdogan would pressure them to drive rates down again. Here, via Trading Economics, is a history of the central bank’s one-week repo rate:

So how’s this working out for Turkey? Did having a leader who will always push for lower rates translate to lower inflation, Erdogan long argued, and and as Neo-Fisherians might predict?

No. No, it did not.

If you look at the country’s inflation rate over the last few years, it’s clear that it’s in an explosive upward spiral:

If the Turkish government doesn’t take dramatic steps to get this under control right now (and we’ll talk later about what those steps should be), this could result in epic catastrophe — the kind of thing that has caused Venezuela to experience utter economic collapse in recent years. We’re talking widespread hunger, lack of basic medical care, and the collapse of sanitation, eventually leading to social disorder and violence.

And this would be doubly tragic, because Turkey had been doing incredibly well prior to the last few years — one of the world’s true economic development stars.

The Turkish miracle

Turkey’s economy was puttering along until the turn of the century — a middle-income country that grew at slow, developed-country rates. But around 2001 or so, it took off; since then its living standards have doubled. Let’s look at its performance relative to Germany (a rich country that invests a lot in Turkey):

Not bad at all. Turkey’s growth path looks very similar to that of East European success stories Poland, Romania, and Hungary, as well as Malaysia.

Personally, I would now rate these as “near-developed” countries.

And how did Turkey do it? Going to the Observatory of Economic Complexity, we see that its exports are pretty diversified, but with the biggest share coming from manufactured goods, especially automotive:

And its customers are also pretty diversified, but with the rich countries of Europe buying the lion’s share:

So at a glance, it looks like Turkey is following a pretty normal path of industrialization: Making a bunch of manufactured goods and selling them to nearby rich regions. A glance at other statistics backs up this story. Turkey invests a lot of its GDP — 32%, the same as South Korea — and there has been an FDI boom since 2001. Manufacturing is 19% of Turkey’s economy by value added, slightly higher than Germany or Poland. Though manufacturing’s share fell in the 00s, it recovered somewhat in the 2010s, and remains reasonably high. Vehicle production has risen sixfold since the turn of the century, and is now about half of Germany’s volume.

Turkey is not a particularly export-oriented economy — exports total only about 29% of GDP, compared to 56% for Poland and 61% for Malaysia. But in terms of what it’s exporting, and what it’s producing, it looks like Turkey has been generally following what I call the Chang-Studwell model of growth — investing in manufacturing sectors that have the capacity to raise the country’s productivity level through absorption of foreign technology, learning-by-doing, and the pressure of competing in high-pressure export markets where product quality and efficient production both matter.

So far, so good. This is how the global economy is supposed to work — poorer countries industrialize and catch up with richer ones. Yes, there was always going to be the inevitable adjustment when Turkey had to switch to innovating and developing globally respected brands in order to make it up to the top tier of wealth, but just making it to $28,000 per capita GDP — about where the U.S. was in the mid-70s — is an enormous achievement.

But there were always three flies in the ointment of Turkey’s long boom. The first was a reliance on external borrowing. The second was political instability, ultimately leading to bad macroeconomic policy. And the third was Erdogan’s bizarre love of low interest rates.

Where did things go wrong?

I’ve visited Turkey only once, in August 2018 for a friend’s wedding (I loved Istanbul and can’t wait to go back). When I arrived in the country, I found that the dollars I had brought in my wallet were able to buy a LOT more lira than I had planned for. While I was en route, Turkey’s currency had crashed. This was the beginning of a crisis that has not really stopped since then.

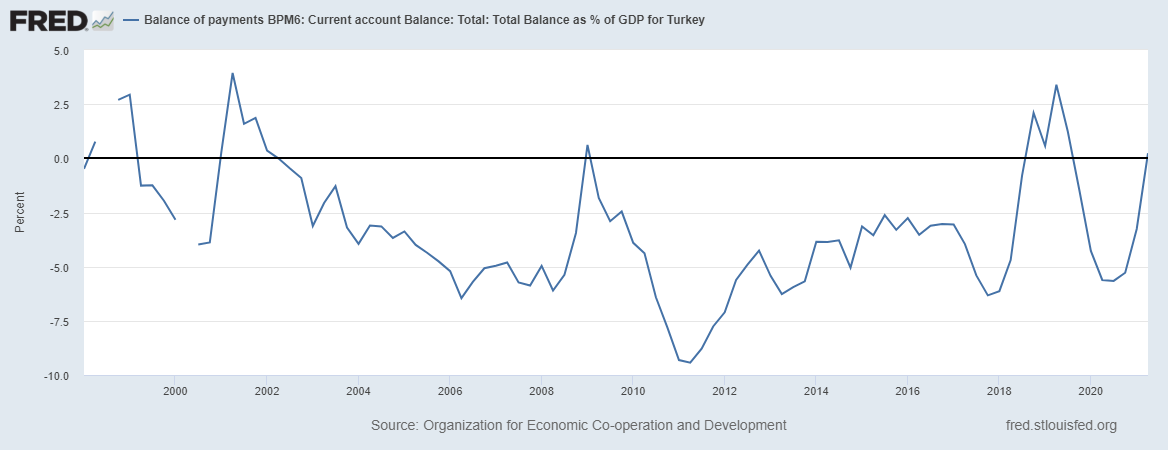

The root of the problem was external borrowing. Turkey’s fairly high investment rate isn’t matched by an equally high savings rate, meaning that it has had to run a big current account deficit:

This led to a big increase in Turkey’s stock of external debt:

A couple of further factors exacerbated this problem. One is that while some of this investment was in the aforementioned productivity-boosting manufacturing industries, a fair amount went into real estate (encouraged by the Erdogan administration) and into grandiose construction projects undertaken by the government. Since many of these projects were undertaken or encouraged for populist political reasons, they didn’t earn a great return on investment and ultimately set the country up for a rapid reversal of capital inflows. The second factor making things worse was that a ton of Turkey’s external debt was short-term, leaving it even more vulnerable to a sudden stop in foreign investment. As Turkish economists A. Erinç Yeldan and Burcu Ünüvar acidly wrote in 2015:

The post-2001 growth…was mainly driven by a massive inflow of foreign finance capital…[T[he high rates of interest prevailing in the Turkish asset markets attracted short-term finance capital, and in return, the relative abundance of foreign exchange led to overvaluation of the Lira…

85 per cent of the current account deficit for the year 2012…was financed by net inflows of portfolio investments and unrecorded capital inflows…Being predicated on portfolio investments and unrecorded capital inflows, the hot money flows present the most volatile form of capital, which is also the most sensitive one to abrupt swings of foreign exchange speculation…

[T]he external borrowing is mostly characterized by short-term structure. The net increase in short-term external debt stock…accounts for 87 per cent of the overall increase.

That set Turkey up for a classic emerging-market “sudden stop”, where foreign investors decide to yank their money and the currency takes a tumble. That’s what happened in 2018 — you can see on the graph of Turkey’s current account, above, that the country swung from deficit to surplus in 2018. And you can see on the graph of interest rates that Turkey’s central bank had to hike rates to keep the outflow from being even worse.

But now let’s ask why Erdogan was so eager to encourage foreign investment into sectors that weren’t going to boost long-term productivity and which set the country up for a crisis. The fairly obvious answer is political instability. Turkey has never been a very stable country; it’s had frequent military coups, festering internal conflicts and foreign wars, and a persistent split between secularists and those who want to bring more religion into public life (like Erdogan). In 2013 there was a huge wave of protests against Erdogan, some of which were violently quelled with dozens of deaths and thousands of injuries. In 2016 there was a failed coup against Erdogan, followed by an extensive round of purges.

Thus, Erdogan has faced persistent internal challenges to his rule. And when populist leaders face challenges to their rule, a very common response is to pump up short-term economic growth in order to shore up political support, even at the expense of long-term productivity growth (in fact, China has done quite a bit of this as well over the years). So that explains why Erdogan has been eager to engage in big construction projects and funnel foreign money into real estate.

In fact, from the current account graph, you can see that after an initial period of stabilization after the crisis began in 2018, Turkey was back to its habit of importing tons of foreign capital — even though growth had now basically halted. This ensured that the economy would become even more vulnerable and that the crisis would continue.

And to top it all off, Erdogan has personally compounded the problems with his strange Neo-Fisherian theory that low interest rates are disinflationary. A year ago, when the currency crisis started up again and the head of Turkey’s central bank raised interest rates, Erdogan fired him and replaced him with a crony who lowered interest rates as his boss demanded.

Well, to be blunt, it’s not working out. Cutting rates increased policy uncertainty and made foreign investors flee, the lira keeps on steadily weakening, and now inflation is exploding. Guess Erdogan’s theory was wrong.

Oops!

How to save Turkey

Turkey has one thing going for it, which is that it’s not (yet) doing the thing that is classically believed to be fuel for hyperinflation — i.e., using central bank money creation to fund government borrowing. Government debt is rising, but not exploding, and is still only 40% of GDP.

That will probably make it easier to stabilize Turkey’s economy and end its 4.5-year-long crisis. But Erdogan is going to have to abandon the idea that low interest rates reduce inflation. He needs to fire his crony from the central bank and bring in an orthodox person who will raise interest rates and keep them high until inflation cools.

Raising interest rates will cause a bit of short-term pain for the Turkish economy, but maybe only a bit. Higher interest rates will bring back some foreign money inflows, as they did when the central bank hiked rates for a while in 2018. That will buy Turkey some time. The government can use that time to implement policies to force both Turkish households and Turkish corporations to raise their savings rates. That will wean Turkey off of the addiction to external debt and stabilize the current account balance, reducing the risk that the economy will be devastated by sudden future capital outflows.

Finally, Erdogan needs to use his near-dictatorial power to channel investment away from speculative real estate or white elephant construction projects, and back toward manufacturing industries. Obviously, as China is now discovering, making that shift can be painful, so it should be done gradually over the next 5 years or more. But basically, this will shift Turkey from a hybrid growth model to a more orthodox one. Erdogan should immediately read How Asia Works — a book I read while I was in Istanbul, as it happens — and then go on to read The Park Chung Hee Era. I hereby offer to send copies of both of these books to anyone in his office who reaches out.

If Erdogan does any of this, it will indicate a remarkable reversal — a highly unusual conversion from divisive populist to forward-thinking industrialist. But hopefully the threat of imminent hyperinflation will have a way of clearing the mind. Turkey’s development in the 2000s and 2010s is just too good a story to throw it all on the fire. There’s still time to turn things around…but not much.

Hi Noah, this is excellent analysis. Big ask but I'll definitely love to read one on Nigeria which I fear is toeing a similarly destructive path via high external borrowing made worse by its flailing manufacturing sector and poor revenue inflows. If you do ever get to do that piece I'm certain it would go very viral as Nigeria is approaching election season. Do consider this please.

Love,

Stephen

Can you do this again, but for Brexit? Bad choices turn out to be bad..