Three more books about the technology wars

"The Wires of War", "Four Battlegrounds", and "The Digital Silk Road"

Since I’ve been writing a lot about industrial competition between China and the developed democracies, I decided to read some books about the technological aspects of this rivalry. The first three I read were Chip War, Wireless Wars, and AI Superpowers, which I reviewed in an earlier post:

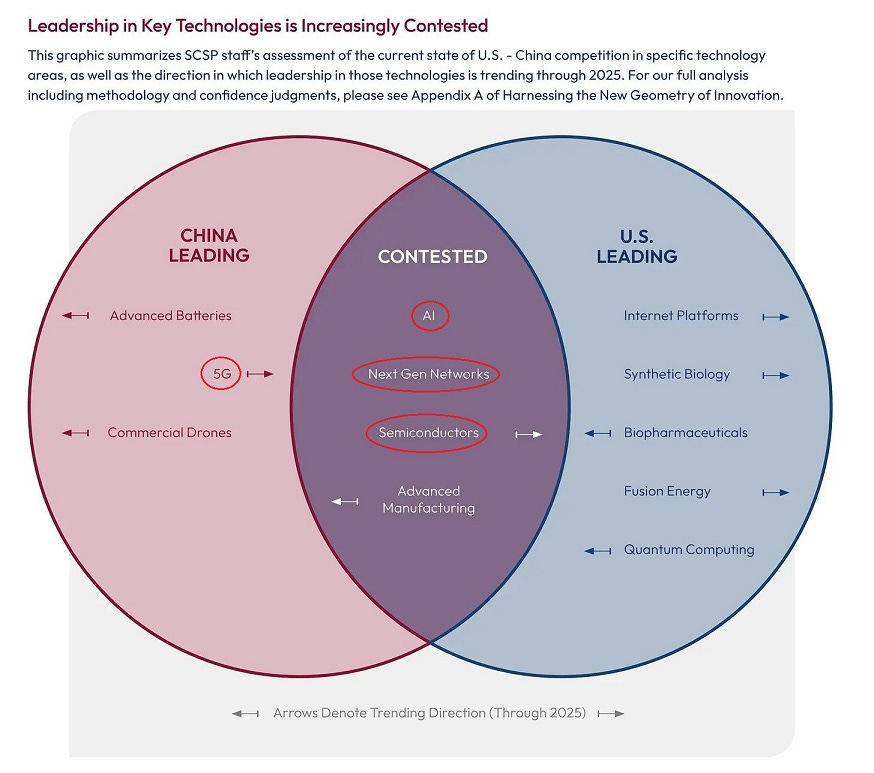

I’m basically working off of the list of “key technologies” identified by the Special Competitive Studies Project, a think tank founded and chaired by Eric Schmidt:

I decided to start with the technologies that are the most highly contested — semiconductors, AI, and networking technology. In the future, I’ll try to find books to read about competition in drones and quantum computing and advanced manufacturing, but for now I’ve maintained the same focus as in my first post.

First a bit of a recap. Semiconductors are really the fundamental underlying technology here, as Chip Wars explains. They’re crucial for precision weaponry, but they also underlie all the other key contested technologies — wireless networking technology relies on chips that switch between data streams, and AI relies on chips like GPUs and ASICs. Take away chips, and you can’t really do anything. So this is why U.S. export controls have focused on the semiconductor industry, and why China is trying so hard to catch up.

Wireless dominance is defined just as much by more than just technological capabilities; since there’s such a strong network effect, whichever provider can underbid everyone else typically gets to be the sole provider for everything. And in the past decade, that has been the Chinese juggernaut Huawei, which has used Chinese government assistance to underbid (and in some cases, destroy) its Western rivals. As Wireless Wars explains, one way to prevent that might be to move to an open system where different providers provide different pieces of wireless tech, allowing America to compete more effectively against China. But open-RAN technology, as it’s called, is still technically challenging.

AI, meanwhile, is the wild card; as we’ve vividly seen with GPT-4 in the past few days, nobody really knows where this fast-progressing field is headed. So who will end up dominating it, or whether it even can be dominated, or what that would mean, is still up in the air. That said, however, AI Superpowers did a remarkably bad job of dealing with the topic — stubbornly avoiding any talk of military applications, and making a bunch of bad predictions about AI that have already been falsified by events.

Anyway, here are some brief reviews of the next three books.

1. “The Wires of War”, by Jacob Helberg

If you’re going to follow in my footsteps and read these books, The Wires of War is the book you should probably read first. It gives a rapid but informative overview of all of the subjects covered in the others. But more importantly, it explains why the developed democracies should be engaging in technological competition with China in the first place. This is the “why we fight” book.

It can be very easy to just assume that the U.S. and our democratic allies ought to try to maintain technological supremacy over China. For many, U.S. hegemony is an end unto itself; for others, the fact that the Chinese Communist Party is a nasty regime that does nasty things to its people is reason enough that we shouldn’t want them to be the world’s dominant power. But for many people in the U.S., those reasons aren’t worth the higher consumer prices and loss of the Chinese market that will result from technological competition, not to mention the taxes needed to fund industrial policies.

The Wires of War explains that the threat isn’t just to U.S. power or China’s oppressed minorities. China and its key ally Russia bear active enmity toward the developed democracies, and even now are hitting the U.S. and its allies with cyberattacks and information operations that, although they fall short of actual war, are clearly hostile acts. Maintaining a lead in chips, AI, and networking technology is important for self-defense — especially if the low-level attacks escalate at some point.

Now, it’s true that Russia has been far more aggressive toward the U.S. and Europe than China has. If The Wires of War has a weakness, it’s that it starts out by mostly describing attacks by Russia, and then pivots to arguing that we need to reorient policy toward competition with China. The argument that we should prioritize competition with our most capable rival instead of our most aggressive rival — which I strongly agree with — requires a nuanced and holistic understanding of geopolitics that the book doesn’t always provide. But overall it does make its case pretty strongly; I expected to find this book overly hawkish, but I found myself nodding along to pretty much everything.

The Wires of War also deals with the disconnect between the tech industry on the West Coast and the U.S. political and defense establishment on the East Coast. In China, companies work hand-in-glove with the military, but in the U.S. they often ignore each other or work at cross purposes. Tech companies can shy away from cooperation with the Defense Department, partly due to pressure from their left-leaning employees. Meanwhile, the DoD and politicians often fail to understand that only Silicon Valley companies have the technological chops to go toe-to-toe with China’s best. On top of that, the defense procurement process is fundamentally broken, with the DoD prioritizing its existing contractors and its expensive legacy hardware over emerging technologies and the startups that create them.

Bridging this east-west divide is Helberg’s major policy focus. In fact, I recently attended a dinner in Washington, D.C. that Helberg hosted, where startup founders and VCs networked with politicians and staffers and discussed the technological-military threat posed by China. The effort is a good start, but it definitely has a very long way to go.

2. “Four Battlegrounds”, by Paul Scharre

This book was everything that AI Superpowers was not. Where AI Superpowers resolutely refused to discuss the military aspect of AI, Four Battlegrounds puts defense applications front and center, painting a vivid picture of how AI-enabled militaries could overrun their adversaries. Where AI Superpowers made a bunch of breathless and confident predictions about how AI will change the world, Four Battlegrounds is circumspect, recognizing the vast uncertainty associated with this fast-emerging technology. And where AI Superpowers evinces a smug sense of inevitability about China’s dominance of AI, Four Battlegrounds is practical in its suggestions for how the U.S. can compete. In other words, Four Battlegrounds is the book I was looking for here.

The book is organized in an unusual and almost haphazard manner. There’s no steady arc or progression to it; each chapter deals with a different aspect of AI competition with China. But in fact, this ends up being one of the book’s core strengths; we know so little about AI at this point that essentially what we have are a series of snapshots, use cases, and conjectures, without much of a grand narrative or deep theory.

If there is a unifying principle, it’s that supremacy in AI will require four key inputs — the titular “four battlegrounds”. AI Superpowers argued that AI supremacy will be determined by a combination of data, talent, and government support. To this list, Four Battlegrounds adds a fourth factor: compute.

Where AI superpowers placed strong emphasis on data, Four Battlegrounds de-emphasizes this factor. Scharre points out that China’s supposed supremacy in data probably isn’t that important, since most machine learning models are finicky and need to be trained on data sets that are very specific to their tasks. China can train its models to recognize the face of every Chinese citizen, but that won’t necessarily help those models to recognize targets on the battlefield.

As for talent, AI Superpowers focused on hard-charging Chinese entrepreneurs, while Four Battlegrounds shifts the focus to AI engineers. Scharre argues that military AI models are so finicky and task-specific that they’ll require constant tweaking by highly trained researchers in order to maintain battlefield relevance.

At this point we run into the fundamental fact of AI talent: Most of the top Chinese talent doesn’t work in China.

How to keep that Chinese talent working outside of China, especially in the case of a major conflict, is a subtle and difficult problem that Four Battlegrounds doesn’t really address. It’s something that we ought to be thinking about very hard.

Finally, there’s compute. AI is incredibly computationally intensive, and the kinds of chips that work best for AI — GPUs and ASICs — are pretty cutting-edge stuff. Although Four Battlegrounds only spends a little time on this fact, the implication is that the AI war could ultimately come down to a chip war.

As for government support, AI Superpowers was written before Xi Jinping’s ham-fisted crackdown on China’s domestic IT industry. But while Four Battlegrounds recognizes China’s stumble, it also points out that the U.S. has what might ultimately prove to be an even greater institutional weakness — the inefficiency of our defense procurement process. The DoD simply doesn’t spend enough on AI, and doesn’t allow AI projects to scale up sufficiently. In fact, broken U.S. defense procurement is a major theme among the books I’m reading these days.

Anyway, if you want to read a book about AI competition between the U.S. and China, Four Battlegrounds is a good one.

3. “The Digital Silk Road”, by Jonathan E. Hillman

This book has an unfortunate title, since there are at least three other books with the exact same name. So make sure you get the right one!

The Digital Silk Road is about networking technology — wireless infrastructure, broadband, internet cables, communications satellites, and networked devices (the “internet of things”). It’s basically a much broader, more comprehensive look at the same topic as Jonathan Pelson’s Wireless Wars, though that means it necessarily deals with each technology in a far more abbreviated fashion. Basically, The Digital Silk Road takes you on a whirlwind tour of all the ways that China is trying to build and control the infrastructure of the global internet.

The one big point from Wireless Wars that gets reinforced in The Digital Silk Road is that networking technology is about network effects. The more nodes and connections of a communications network you control, the easier it becomes to increase your control over the remaining nodes and connections. This is a competition that naturally favors China; though its pockets are no deeper than those of the U.S., China is far more willing to spend government money helping its companies win bids and build infrastructure. Because the U.S. and its allies are typically stingier with government support for private companies, China has a structural advantage in its quest to own the internet.

The Digital Silk Road is a bit light on arguments for why we should ramp up public support, however. There are a lot of bad things China could (and probably would) do to us if it controlled the world’s internet infrastructure — disrupt our military operations, spy on us, launch cyberattacks, and so on. But because it doesn’t discuss these scary possibilities very much, The Digital Silk Road leaves the reader wondering how to prioritize our countermeasures against Chinese control. Is it more important to get U.S. satellites into low Earth orbit, or prevent China from running data cables between Africa and Latin America? A bit of perspective on the relative importance of the various threats would help.

Despite that weakness, though, The Digital Silk Road is a highly informative book. It explains each technology succinctly and clearly, and offers reasonable suggestions on ow the U.S. can counter Chinese inroads.

In general, the book leaves me pretty pessimistic about the U.S.’ ability to shut China out in any of the areas it discusses — network effects are strong, but China will probably be willing to operate its own global internet infrastructure even if that requires operating them at a loss. The bad scenario here is total Chinese domination of the internet, while the good scenario is that communications networks will be contested for the foreseeable future.

A quick personal note on the military applications of AI, having worked as a high tech communications equipment contractor to the U.S. military I can assure you that the DOD contracting system is seriously flawed. It is designed to create competition rather than collaboration and there is a definite lack of focus needed in pioneering new technologies.

Also, your chart showing that a majority of AI researchers are schooled in China but many migrate to the U.S. may be based on outdated data after the passage of the "Chip Wars" act attempting to onshore chip production to the U.S.

I would predict that this is not only a futile boondoggle but the Sinophobic backlash will likely send many native Chinese back home seeking more lucrative jobs and less discrimination. As DougAZ's comment on this string indicates, Chinese scientists are deemed an "enormous National Security concern" just because they're Chinese. The AI brain drain is likely to change course as China ramps up its efforts to develop alternatives to U.S. standards and procedures.

Excellent-sounding recommendations, although I worry that books on AI coming off the press this year will be obsolete in another year. The scrum of emails I see each morning about the previous evening's experiences with and impressions of ChatGPT, Bing and Bard is overwhelming. And the silence so far from Apple is deafening.

I can wait for what you discover with quantum computing, but drones in the Ukraine are metasticising and it may be high performance computing of the traditional sort (on distant servers) that makes the difference. Instead of one drone plus one pilot plus one guy coordinating with artillery, we may already be seeing drone squadrons, with a single "officer" in control and intelligence C&C coordination. There have been cool Ted demos with the consumer gear for a few years now.