Three economics happenings of note

Noncompetes, declining disruption, and an inflation debate

A lot of interesting stuff is sort of whizzing by right now, so I thought it was time for another newsletter-type post. I’ll try to go in order from least wonky to most wonky (though let’s be honest, they’re all pretty wonky). Anyway, I don’t often do these multi-topic posts, and I’m not sure how much people like them relative to the typical single-topic posts. So if you have any feedback about these, please leave it in the comments or email me!

Anyway, let’s get to the fun stuff.

The war on noncompetes

Over the past couple of decades, a lot of economists have been thinking about ways to raise wages. Many ideas have been proposed — raising minimum wage, empowering labor unions, curbing occupational licensing, etc. But one of the most popular ideas has been to ban noncompete agreements. Noncompetes are clauses in a worker’s employment contract that specify that if the employee leaves the company, they won’t go work for a competitor for a set period of time. This type of agreement is very common — around 18% of American workers are currently under a noncompete, and they’re common across all industries. Noncompetes are more common for higher-end knowledge workers (since these people tend to take valuable knowledge with them when they jump to a competitor), but they’re surprisingly common at the low end as well — the issue jumped to national prominence in 2016 when Jimmy John’s, the fast-food sandwich place, got busted by the state of New York for making low-wage workers sign noncompetes.

Now the FTC has embraced the idea that noncompetes are a threat to competition, proposing a total national ban on the practice:

For the economists who have been yelling about this for a few years now, it must be gratifying to see the government come around so quickly to their position — and in fact, the FTC proposal follows on the heels of various recent state-level actions against noncompetes. So this idea has been more or less building to a consensus.

So let’s talk a bit about why people think this will raise wages. Basically, if you’re a worker, the ability to switch jobs gives you two things — first, it lets you find an employer who’s willing to pay you more, and second, it lets you ignite a bidding war (or even just threaten a bidding war) in order to get your current employer to give you a raise. If there’s no possibility of going to work for another company in the same industry, you’re much more trapped at your current job, meaning that unless you’re willing to switch industries or move far away, you’ll just accept whatever wage they give you.

This theory is generally borne out by evidence. For example, Lipsitz and Starr (2019) find that a 2008 Oregon ban on noncompetes for hourly workers ended up raising wages for low-wage workers as a whole by about 2-3%, and for workers bound by noncompetes by as much as 14-21%. Another study by Balasubramanian et al. (2022) looked at a noncompete ban for tech workers in Hawaii and found similar positive effects on wages. Importantly, these wage boosts seem to be very long-lasting.

Businesses who want to use noncompetes basically counter this by arguing that noncompetes make them more willing to hire and train workers in the first place, since the risk is lower that those workers will just jump ship to one of their rivals at the first opportunity, taking valuable knowledge and expensive training with them. There is some evidence for the training part of this argument. Starr (2019) looks at changes in the enforceability of noncompetes at the state level, and finds a tradeoff:

An increase from no enforcement of noncompetes to [an average level of] enforceability is associated with a 14% increase in training, which tends to be firm-sponsored and designed to upgrade or teach new skills…Despite the increases in training, an increase from non-enforcement of noncompetes to mean enforceability is associated with a 4% decrease in hourly wages…[L]ess-educated workers experience additional wage losses in the face of increased enforceability relative to more-educated workers.

But it’s worth asking why, as a society, we should value agreements that increase worker training if those agreements decrease workers’ wages overall. You basically have to argue that the social benefit of having a more highly trained workforce outweighs the social cost of having a lower-paid workforce. And that’s a hard argument to make.

There’s also a whole second dimension to the noncompete debate, which involves innovation. Businesses also commonly argue that noncompetes allow them to invest more in creating new technologies, since they can be more confident that their ideas won’t leak to their competitors via wayward employees. And in fact there is evidence for this; Conti (2013) finds that in states that strictly enforce noncompetes, companies do riskier research.

But opponents counter that noncompetes quash innovation by preventing new companies from entering an industry (because they can’t get good employees). In fact, Berkeley’s AnnaLee Saxenian, probably the premier historian of Silicon Valley, claims that California’s refusal to enforce noncompetes was a big part of why the IT industry ended up clustering in California rather than Massachusetts, Texas, or elsewhere. (If you have a chance to read Saxenian’s book Regional Advantage, I highly recommend it.) And there’s lots of evidence to support this argument as well; papers by Jeffers (2019), Starr, Balasubramanian, and Sakakibara (2017), and Samila & Sorenson (2009) all find that noncompetes reduce the number of new entrants into an industry.

Balancing all of these considerations is difficult; we can make theoretical models, but no one will really believe their verdicts. It’s really more about the type of economy we think will be better overall. An economy with strong noncompetes will be a little more like Japan — workers will be better trained but will switch jobs less and make lower salaries, big dominant companies will do more R&D but disruptive new startups will be shut out of the market by lack of personnel. It’s about the choice between a dynamic, competitive economy and one dominated by big, secure companies. Personally, observing the outcomes in both the U.S. and Japan, I’m inclined to go with the former.

Is science becoming less disruptive?

One of the most worrying trends in economics is that we keep spending more and more on research, but our productivity growth doesn’t seem to speed up much. The most important paper showing this is Bloom et al. (2020). Technological progress is not just the ultimate source of all our material wealth, it’s our most effective weapon against existential challenges like climate change. So the prospect that progress might simply get too expensive for our society to sustain is fairly scary.

There are various hypotheses for why research is getting less productive on average. One is the “low-hanging fruit” hypothesis — the idea that there are a certain number of relatively easy, relatively high-impact discoveries to be made, and that we’ve already made most of these. There’s only one periodic table, one structure of DNA, and one Schrödinger Equation, just like you can only invent electric power, the internal combustion engine, semiconductors and sewage treatment once. The alternative “burden of knowledge” hypothesis is that there’s plenty of new big stuff left to discover, but scientists just don’t have enough time in their lives to discover it, because the corpus of existing knowledge keeps on increasing, requiring them to spend more and more of their productive lifetimes simply getting up to speed. There are other explanations too, and it’s important to note that these hypotheses aren’t mutually exclusive.

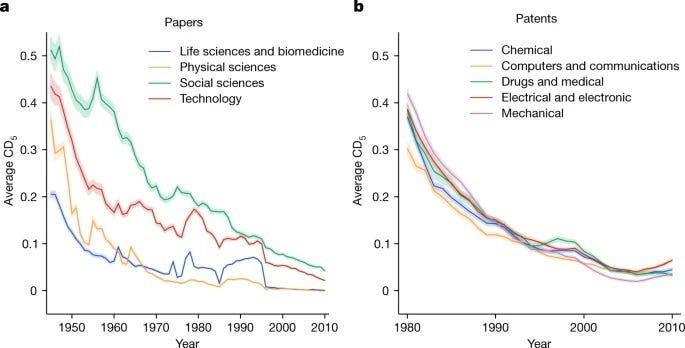

Anyway, a very interesting paper just came out in Nature that offers both new evidence and a new perspective on this debate. In “Papers and patents are becoming less disruptive over time”, authors Park, Leahey, & Funk argue that game-changing scientific research is becoming less common.

The way Park et al. measure the “disruptiveness” of a paper is, basically, how much of a break in the literature it causes. If a paper really changes the state of our knowledge, the reasoning goes, then subsequent papers in the field will tend not to cite research that was done before the breakthrough. If you have Newton, you don’t need Aristotle. So the authors measure a paper’s disruptiveness with something called a CD index, which represents the likelihood that later work that cites that paper will also cite things that the paper itself cites. For example, if Jim writes a paper that cites Giacomo, and Diego writes a paper that cites Jim, then the CD index of Jim’s paper will go down if Diego also cites Giacomo, because that means it’s more likely that Jim’s work didn’t eclipse or replace Giacomo’s.

I hope that made sense. Anyway. The authors find that their measure of disruptiveness has been falling across a wide variety of fields, for both papers and patents:

They argue that the similarity in the decline between different fields is evidence against the idea that we’re picking “low-hanging fruit”, because we wouldn’t expect the easy discoveries to be mined out at similar rates in different fields. I’m not quite sure I buy that; for patents the lines all match up, but for the broad categories of science papers they don’t really match up. It would be interesting to see exactly what Park et al. think a “low-hanging fruit” effect would look like on these graphs. But anyway.

When you see citations in a whole bunch of fields change in the same way at the same time, one obvious thing to suspect would be that citation conventions in academia are changing. Maybe citing older work, even if it’s wrong and useless, is just more in vogue now. Maybe the infamous “Reviewer 2” — a nickname for a hostile peer reviewer is forcing scholars to cite their own outdated work. The authors try to deal with this hypothesis via three methods: 1) use several similar alternatives to the CD index that adjust for papers with unusual citation practices, 2) control for a lot of variables, and 3) do some simulations where they rearrange citation networks while keeping certain numerical attributes the same. For all these methods, they find that their measure of disruptiveness still declines.

To be honest, though none of these methods is entirely convincing — it’s good that they tried these things, but none of them really rule out the idea that a cultural or institutional change among researchers has increased the incentive to cite older, less relevant work. They all seem like they might simply be conditioning on the dependent variable, by assuming that a change in citation culture would have to be somehow different from the thing they’re measuring. I think more digging is warranted in this regard, since changing academic culture is such an obvious candidate reason why totally separate fields might all look the same.

An alternative explanation is that academia and patent law have both changed so as to encourage an increasing amount of crappy useless research — as a signaling mechanism for academic jobs, and as a way of patent-trolling or defensive patenting in industry. This might be supported by the fact that the number of publications has absolutely exploded since the 50s, while by Park et al.’s count the total number of very “disruptive” papers has held steady in most fields (and actually increased in life sciences). That could indicate that we’re still finding all the good stuff, but that we’re also paying people to do a lot of useless crap on top of that. Which would also explain Bloom et al.’s finding that the number of researchers has gone way up without increasing productivity growth; maybe most of those researchers just aren’t very good.

Park et al. claim that this isn’t the answer, because when they look only at top journals, they find the same decline in disruptiveness. But this assumes that top journals are doing a good job of finding and publishing the breakthrough stuff, which might not be true. In any case, I think the “publish or perish” hypothesis also deserves more looking into.

The authors’ preferred explanation for the decline in their measure of disruptiveness is that researchers are using “narrower portions” of existing knowledge. As evidence, they show that citation diversity is down across fields — in other words, more and more, papers are citing the same stuff. They also offer a couple of other measures that seem less convincing (e.g. mean age of citations is increasing; but this is just the headline result, restated). But in any case, they offer little explanation for why this would happen, or why the trend would be similar across fields. Why would biology, materials science, and economics all trend toward narrower knowledge bases at roughly the same rate? Perhaps the trend the authors highlight is due to groupthink, or the silo effect, but why should those forces apply equally in different fields at the exact same time? The authors should take the critique they applied to the “low-hanging fruit” hypothesis and apply it to their own chosen explanation as well!

But anyway, it’s also possible that the rate of decline simply isn’t as uniform across fields as the authors claim. Pierre Azoulay, probably the premier economist working on topics like these, responded to the paper on Twitter. Looking only at papers in the life sciences, he calculated measures of disruptiveness similar to the ones used by Park et at., and found that the decline in disruptiveness basically halted in the 80s:

So I think this shows that other researchers need to dig their teeth into Park et al. (2023) and test both the author’s theories and the robustness of their data itself. But I think it’s undeniable that Park et al. have made an important contribution to the literature and to the debate, and that people will be talking about this work for years to come.

Update: Matt Clancy, whose Substack I highly recommend, has a really excellent thread pulling together a lot of different pieces of evidence on the question of whether science as a whole is getting less novel over time:

Macroeconomists think about how inflation works

I was traveling, and checking Twitter less, so I missed an interesting discussion the other day among some eminent macroeconomists about how inflation works. In general I think inflation is an extremely under-studied and under-theorized phenomenon these days — most of our theory comes from the 70s and 80s. That’s probably due to the decades of low inflation that we enjoyed up until 2021; macro has a tendency to fight the last war. But anyway, it’s good to see the topic getting mulled over again.

The debate centered around a thread written by Olivier Blanchard, asserting that inflation is the outcome of a distributional conflict:

The basic point here is that in one standard theory of inflation, companies try to raise their prices because workers’ wages are going up, and workers demand raises because prices are going up, and this reciprocal process of attempted one-upmanship leads to inflation. Paul Krugman explained this idea in a column entitled “The Football Game Theory of Inflation”, where he likened the process to a football game in which everyone tries to stand up to see over everyone else, and the result is that no one can see better than they could before, but now everyone’s legs are tired. In this analogy, the Fed makes everyone sit down by making the game less interesting, reducing exhaustion at the expense of increased boredom.

Both Blanchard and Krugman wonder if there isn’t a better way. If everyone could just agree to sit down even when the game is at its most exciting, then we could restore a good equilibrium costlessly. Blanchard and Krugman yearn for a planning regime where the government basically coordinates between companies and workers, getting the former to agree not to raise prices if the latter agree not to demand higher wages. You could probably model this sort of thing with game theory, though who knows if it could ever really work in real life (Blanchard is not optimistic).

Now, you might recognize Blanchard and Krugman’s description of inflation as a “wage-price spiral”. Though some, like Jason Furman, have talked about the current inflation as a wage-price spiral, most people have rejected this notion, because of the simple fact that wages are failing to keep pace with prices. But Ivan Werning, one of the top younger macroeconomists out there, argues (using some slides from an unfinished paper with Guido Lorenzoni) that you can have a wage-price spiral even with falling real wages:

In essence, workers’ attempts to force their wages to keep pace with price increases end up failing, but pushing inflation even higher in the process. In Werning’s model, you can get this effect even when the inflation is caused by a demand shock, as long as prices are able to change more easily than wages (i.e. they’re less “sticky”), and production requires a lot of inputs that can’t easily be replaced with more labor. The model is pretty neat, though it does produce some odd predictions for real wages oscillating back and forth.

Ricardo Reis (yet another eminent macroeconomist) then jumped in to offer another reason why a wage-price spiral might not be the best way to think about the current inflation. He noted that although labor seemed like the most important variable cost that companies faced back in the 70s, more recently the labor share of income just hasn’t been very correlated with companies’ costs:

In other words, if labor just isn’t that big a factor in companies’ costs, then maybe there’s not much reason to think that workers demanding higher wages is pushing up inflation a bunch now.

Werning, though, points out that his new model is a bit different from the standard model. In his model, labor and wage demands end up driving inflation even though labor isn’t the most important production input. Tweak the assumption, he argues, and a wage-price spiral could still be there.

And this should demonstrate what’s so frustrating about macro theory. Seemingly innocuous or abstruse tweaks in assumptions can totally change a model’s results, to the point where it changes our whole conception of where inflation comes from. And these changes come with big, important policy implications, like whether we might ever try to control inflation by persuading workers not to demand higher wages in exchange for companies not charging higher prices. The fate of countless workers could hinge on which highly oversimplified stylized toy model we choose to put more faith in.

But anyway, I’m glad macroeconomists are thinking hard about this stuff once again.

I really disagree with this "low-hanging fruit" idea. I used to work as a theoretical physicist at a major university until around ten years ago, and the problem I saw then was certainly not a lack of good ideas to work on. I had far more good ideas than I knew what to do with, and so did most of my colleagues.

The problem is that academia is just a shithole--poor funding, time increasingly consumed by administrative tasks, micromanagement of every activity, and absolutely insane decisions being made at really every turn.

Undergraduates are required to buy low-quality intro textbooks costing upwards of $500 (which you have to buy slightly different versions of every quarter for multi-quarter classes), are given department-assigned and graded homework and exams (professors were forbidden from doing either because the committee knows best), are largely unprepared (many didn't have a good grasp of even algebra), etc...

I just don't honestly see how anyone can look at a situation like that and say "yeah the problem is obviously that there are no good ideas left." The problem is that academia is oppressive, frustrating, and demoralizing, and it just isn't possible to consistently do good work in an environment like that. Pick up, say, one of Feynman's autobiographies and compare his academic experiences to a modern university.

Love how noncompetes are non-enforceable in California. We're not unionized (very few physicians are) so it's the best pressure point we have against management and to reset some internal power dynamics.

Medicine doesn't have any proprietary knowledge when it comes to patient care so noncompetes are just anti-labor, especially since there are only a few practice opportunities in a region.