“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

For years now, I’ve been thinking about what the next big organizing principle of U.S. political economy will be. By “political economy” here I mean the type of economic policies we carry out, and the ways that we expect those policies to reshape our economy. This will be the first in a series of posts laying out my predictions for what the new paradigm will look like.

From the late 1970s through the middle of the 2000s, our organizing principle was what some people call “neoliberalism” — deregulation, tax cuts, free trade, and the shift of the welfare state towards in-kind benefits and work requirements. The reasons we went down this road were complex, and the results were mixed. This replaced an earlier paradigm that people called “the New Deal”, which started to emerge during the Great Depression but really solidified during and just after WW2. That paradigm involved large-scale government investment, heavy regulation, high taxes, social insurance, and the encouragement of a corporate welfare state.

Ever since the financial crisis and the Great Recession of 2008-12, we’ve been looking for a new organizing principle. Obama didn’t really try to give us one; with the exception of Obamacare, he was mostly focused on crisis recovery and damage control (stimulus, financial regulation, boosting the welfare state incrementally along largely neoliberal lines).

But everyone knew a new paradigm was needed. The question was what it would be.

It isn’t going to be climate change

During the decade that followed our emergence from the Great Recession, I participated in a large number of discussions about the idea of a new paradigm. The general consensus among the intellectuals I talked to was that the new economy would be organized around the fight against climate change. Rapid decarbonization would require large increases in both government investment and regulation. Some added the idea of an expanded welfare state in order to ensure broad popular buy-in and to limit the number of people who personally lost out from the shift. Many argued that the struggle against climate change would be similar to a war, echoing Jimmy Carter’s rhetoric about energy independence. Ultimately, these ideas culminated in the Green New Deal introduced in 2019.

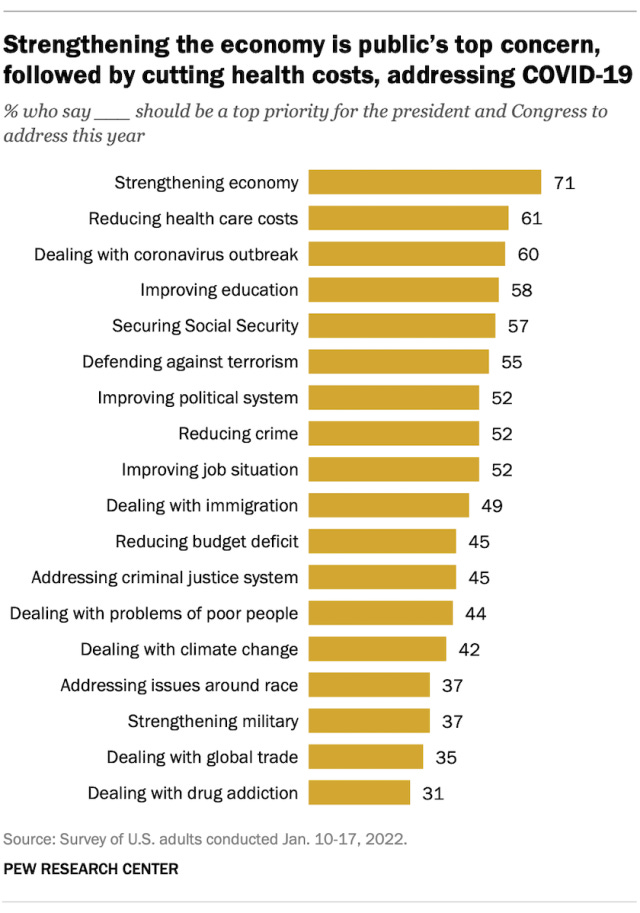

This idea produced a lot of interesting thinking, and I was generally on board. But at this point I would say that “climate change as war economy” has pretty clearly failed to catch on. The fundamental problem is that people in the U.S. — and perhaps in other countries — don’t see a need to reorganize our society around the fight against climate change. Here’s a representative poll, but there are many many others like it:

And when asked about what they’d be willing to sacrifice economically to fight climate change, Americans opposed even the mildest costs — and this was in 2019, before the runup in gas prices that has enraged the country:

Americans’ failure to prioritize climate change, despite the very real threat and constant dire warnings, has been reflected in policy outcomes. The Green New Deal died instantly. Other similarly ambitious climate plans were largely ignored, even by Democratic primary voters. Biden’s scaled-down energy overhaul was defeated by the defection of a couple of Democratic senators, and now even his incredibly modest slimmed-down version has met a similar fate.

Now this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t reorganize our economy around a generational struggle against climate change. We absolutely should, especially because this would also deliver us cheap abundant energy. But we’re simply not going to do it, at least not until it’s too late. That’s the problem with political economy — it’s a delicate dance between technocratic objectives and popular buy-in.

(Of course we still do need to fight climate change, which is very real and extremely scary. But this will have to be accomplished through means other than a Green New Deal. I’ll write more about what the Plan B will be, but this post will give you the basic idea — basically it’ll be more like guerrilla warfare than a big push.)

So if it’s not climate change, what will be the thing that forces us to come up with a new policy paradigm? If it’s not the moral equivalent of war, perhaps it’ll be the threat of actual war.

Signs and portents

I started thinking about the economic importance of geopolitical competition and conflict about four years ago. I wrote a Bloomberg post about how a clash between the U.S. and China was a bigger financial risk than people seemed to realize. In 2019 I conjectured that big tech companies might evade antitrust action by helping the U.S. security services in their competition with China and Russia. Then in 2020 I wrote that technological progress might rotate toward military technology — a view being embraced by some technologists such as Katherine Boyle.

Part of the reason I started thinking along these lines was China’s increasing attitude of belligerence, which of course came at the behest of Xi Jinping but which had been in the works for a while longer. But part of it came from Donald Trump.

For all his ineffectuality and malevolence, Trump was the first major U.S. leader to actually try to shift our political-economic paradigm. His signature policy initiative was an attempt to reshore American manufacturing and use protectionist policy to out-compete China. He was utterly unsuccessful in this objective. The trade war hurt China’s economy but didn’t cause manufacturing to come back to America, and Trump’s other policies — a boondoggle factory in Wisconsin that never materialized, jawboning companies not to send jobs overseas, etc. — failed spectacularly.

And yet, Trump sparked what looks to be an enduring shift. While Biden has (sensibly) ended the trade war against U.S. allies like Mexico, Canada, and Europe, he has not ended Trump’s trade war against China — if anything, he has doubled down. Biden has also made reshoring supply chains a centerpiece of his economic message. And efforts to boost American manufacturing investment have accelerated under Biden, and are now starting to yield a few results.

It was also under Trump that the U.S. government began to take concerted action against Chinese influence in the U.S. economy on a wide variety of fronts — limiting Chinese investment via CFIUS, implementing export controls (which also prevented Chinese nationals from rising to high positions in many U.S. tech companies), and trying to hunt down spies in academia. These efforts varied in their usefulness, but they all shared a common purpose, which was to disentangle the U.S. and Chinese economies.

Then came the Ukraine War. Russia’s invasion provided a moral clarity that had been lacking in much of our political discourse — a clear case of a brutal and savage aggressor attempting an unprovoked imperial conquest of a peaceable neighboring country. U.S. efforts to support Ukraine with all means short of war led to the creation of a vast and powerful new sanctions regime. Because many sanctions also apply to companies that do business with Russia, there’s a possibility that the new regime may accelerate an exodus of American, European, and Asian countries from China. It also may end up dividing the world into two economic spheres — a pro-Russia-and-China sphere and an pro-U.S. sphere. (We might tentatively call these the New Axis and the New Allies.) A combination of reshoring, near-shoring, and “friend-shoring” — moving production out of China and its allies into countries friendly to the U.S. — may blossom into a full reorganization of global supply chains.

And the Ukraine war may be just the beginning of a new age of geopolitical competition. A Chinese scholar recently wrote that “countries are brimming with ambition, like tigers eyeing their prey, keen to find every opportunity among the ruins of the old order.” Not least among those tigers is China itself, which many observers believe is edging closer to an invasion of Taiwan:

This would, of course, bring the U.S. and Japan into direct conflict with China. Both President Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio have been highly vocal about the need to protect Taiwan.

This is not to say that the competition with Russia and China is a simple good-versus-evil struggle. And it’s not even to claim that it’s the most important political struggle in the world right now — preventing the rise of autocratic leaders in democratic countries like the U.S. and India is just as important, if not more so.

Nor do I want to come off as eager for a clash. I still think the likeliest outcome by far is that we’re able to stop great-power competition from escalating to all-out war — Cold War 2 rather than World War 3. I use the term “War Economy”, but like in the 50s and 60s, that doesn’t require an actual hot war between great powers, and I fervently hope there won’t be one.

But in any case, despite my wishes, the world is probably entering an era of intense geopolitical competition, the likes of which haven’t been seen at least since the 1970s and probably since the 1930s. And that competition has the potential to provide a legitimating mission for the reintroduction of the kind of large-scale economic planning that many people have been looking for since 2008. We may not be able to prevent the new era of conflict, but in some ways we can take advantage of it — and in any case, we must do what needs to be done.

The basics of the War Economy: production and planning

So what would the War Economy look like? It helps to look at history here. The closest analog has got to be the mid-20th century period, starting with the New Deal and lasting into the early decades of the Cold War. Policymakers first started groping toward a greater role for government in order to battle the economic disaster of the Great Depression, but there was a ton of resistance and pushback — from entrenched interests, but also just from the natural conservatism of the policymakers themselves, who had been raised to believe in ideas of laissez-faire and self-reliance and were reluctant to toss those completely out the window. It was only the extreme exigency of World War 2 that prompted a full shift to planning and high taxes. And elements of that model were continued after the war, during the early stages of the contest with the USSR — research spending, massive infrastructure construction, support for big manufacturing companies, education spending, social insurance, heavy regulation, and so on.

I am not claiming that all of what we did during that era was effective — indeed, a great many mistakes were made, and we should learn from those mistakes and do better this time. But the overall contours of the problem are similar. We are in a technological, economic, and arms-race competition with enemies with highly advanced tech capabilities, tons of production potential, and far fewer scruples than we have regarding the use of government power. We are not going to be able to deal with that problem by cutting taxes and opening our markets to more Chinese-made products and twiddling our thumbs and intoning quotes from Milton Friedman. Everyone except a few die-hard ideologues and vested interests realizes that on some level by now.

We are going to need to increase planning for one reason: National defense is a public good. Indeed, it is the most classic, most fundamental public good. Private individuals, left to their own devices, will simply not contract with each other to provide effective defense against Russian rockets or Chinese drones; we need a strong government to handle the threat from other strong governments. And since defense requires a huge technological and industrial supply chain in this day and age — you can’t just have a bunch of minutemen pick up their muskets and walk off to defend the country — the public good of defense-oriented planning is going to reach deep into many sectors of the economy. Modern Russia’s technological weakness should provide us with a cautionary tale of what happens when you neglect the economic and technological foundations of military strength.

We are going to need government-funded R&D. Public-private defense partnerships. A bunch of startups in the defense contracting space. Incentives to friend-shore supply chains. Programs to ensure supplies of critical raw materials. Strategic trade agreements to bolster our allies’ economies and weaken our enemies’ economies. Enhanced export controls. Financial policies to prevent our capital from being captured by rival governments, and to prevent technology from leaking via foreign investment. And so on. And funding all this may require substantial new taxes, or cutting back temporarily in other areas. But we shouldn’t be driven by ideology — building a stronger economy will likely require targeted deregulation in a number of areas.

We can already see some tentative initial moves in this direction. The CHIPS Act, a semiconductor industry promotion bill, is just one small example of the kind of enhanced industrial policy we’ll need. That bill is now floundering in Congress, thanks to the standard dysfunctionality of our legislative system and threatening a whole lot of semiconductor manufacturing investment plans. And even that bill is a massively pared-down version of a much bigger and better initiative to revitalize U.S. research spending. So although we’re starting to think along the right lines, we’re going to need to build the political will and state capacity to do much more than what we’re doing.

But defense isn’t the only aspect of the War Economy. There’s also the issue of popular buy-in. Foreign threats are a distant abstraction for the vast majority of Americans; ensuring popular support for the economic changes necessary to meet those threats will have to be a key part of the War Economy. It certainly was so in the Cold War, when we created a welfare state even as we beefed up our capacity to resist the Soviets. National unity will probably require both economic redistribution of some sort and social policies to foster a sense of inclusiveness.

So the idea of the War Economy is not an alternative to the idea of New Industrialism or the Abundance Agenda that I’ve been talking up over the past two years. Indeed, the two are closely interrelated.

This is the first of a series of posts I’m going to write about the idea of the War Economy. Here’s a list of the follow-up posts I have planned so far:

The capabilities of the competition (the “New Axis”), and what will be required to match them

Specific industrial policy ideas for the War Economy

How the War Economy could incorporate redistribution and with social justice

Pitfalls and dangers of the War Economy, and how to learn from the mistakes of the New Deal era

For today, I just want to sketch out the idea in very broad strokes. We’re entering the sort of time that I wish I hadn’t had to live through — a dark time when our way of life is under threat by both internal conflict and external enemies. That will require a response of the sort our nation hasn’t been forced to muster in over half a century, and we need to be psychologically prepared for that. When you live in dark times, the only thing you can do is deal with them, and fight for a brighter future.

My series of posts on the War Economy continues here.

Noah. We need much more:

1. Skilled immigration

2. An industrial policy

3. Housing and transit

4. STEM education

We need all of the above. And the time is now. Much much more needs to discussed, and actioned Into policy on all fronts.

Abundance agenda + industrial capacity + Growth mindset.

Noah, I'm really puzzled as to why you so consistently frame Russia and China as an "axis" with common interests and requiring a common response. The two countries look very different to me. Russia is a declining petrostate with a weak manufacturing base. The poor performance of its armed forces in the Ukraine is consistent with a government which doesn't depend on a functioning economy or skilled workers for power because it can fund itself on raw materials. China, on the other hand, is a functioning industrial economy with a fairly strong technical manufacturing base and an increasingly skilled workforce. Importantly, because it is not a resource extraction based economy, China requires a functioning society and the Chinese political elites have to bring their population with them in a way that is not the case in Russia.

True, both countries are somewhat hostile to the USA at the moment, but this seems to be fundamentally different in nature. Russia needs foreign enemies to fight (and cheap successes) as the government has no other real source of legitimacy. Russia is also no a serious geo-political rival to the US (if you are failing in an invasion of a poor neighbouring country of c40m people with a weak military by definition you are not a great power).

China, on the other hand, is a geopolitical rival to the US and has the economic and military power to match. However, although its interests run counter to those of the US in a bunch of areas, there are also significant areas of common interest. Trade, for example, remains central to the health of the Chinese economy (and therefore the Chinese government).

I see little evidence of a China/Russia axis against the US (and the West more generally). This is partly simply because the relationship is so uneven (China + Russia might be a viable competitor to the US, but this would also be true of China + Lichensten - China is doing all the work in both cases).. There is little evidence of China offering Russia much active support in the Ukraine and China's interests don't really seem to align with Russia's here. I doubt that China's government is particularly sad that Russia is giving the US and Europe trouble, but I also doubt that China would make any significant sacrifices for Russia or for any "common cause" with Russia.