The U.S. education system gets decent value for money

Debunking a common myth

I’m a reasonably big critic of the U.S. K-12 education system. I think we focus too much on identifying talent and not enough on producing skills. I think we focus too much on top performers and not enough on the broad middle. I think we should reform the way we teach math, to emphasize hard work and step-by-step problem solving instead of natural ability. I think more interstate harmonization of curricula would be useful. Etc.

But there’s a persistent belief among some Americans that our education system is low-quality. A lot of people seem to think that the U.S. spends a ton of money on public education and gets very little value in return. This belief is especially popular among conservatives, who tend to frown on public education as an institution. Here are a couple examples of tweets I’ve recently received that express this belief:

But this common belief is wrong. The U.S. education system could use a lot of improvement, but as things stand it’s pretty decent. There are three basic facts that, taken together, demonstrate that we get pretty good value for our money:

Our education system produces generally above-average results.

Our education system doesn’t really cost a lot.

Spending more on public schools pretty reliably improves outcomes.

Let’s go through the evidence for each of these facts.

U.S. education is above average for a rich country

There are two systematic large-scale comparisons of international academic performance: the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). So let’s look at how the U.S. does on both of these.

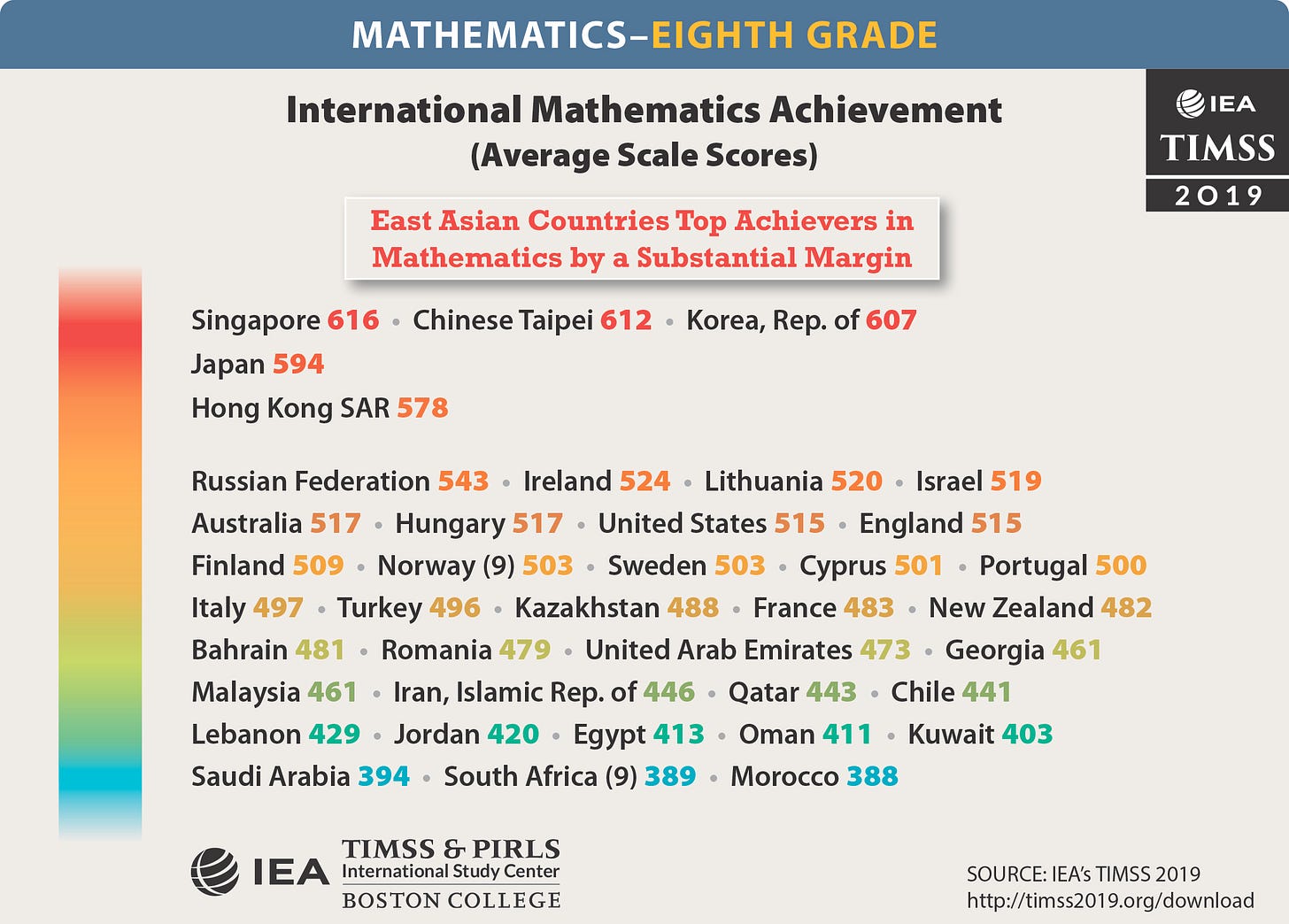

First, TIMSS. This study measures math and science aptitude at the equivalent of 4th grade and 8th grade. 4th grade results are kind of interesting, but I think we can agree that the 8th grade results matter more. Here are math results for the latest survey in 2019:

You can see that although the U.S. doesn’t do as well as top performers like Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea, we beat the Scandinavian countries and many other European countries. That’s not bad! And we do just about the same in science, scoring ahead of Israel and Hong Kong:

On PISA, which measures the skills of 15-year-olds, we do slightly worse. But we’re still pretty respectable in reading and science:

In reading, we’re a bit above the OECD average of 487, and we do better than the UK, Japan, Australia, Taiwan, Norway, Germany, and plenty of other countries. That’s not bad! In science we also beat the average, though by a little less, doing about as well as Australia, Sweden and Germany.

Only in math do we really lag, coming in significantly below the OECD average. This sort of contradicts the TIMSS results, where American 8th graders (age 13-14) did well above average. Looking at the methodologies of the two surveys, I don’t think I have a strong position on which one we should believe more. The U.S.’ weak results on PISA math mean we should work on improving our math education. But overall, the U.S. does above average for a rich country.

These assessments measure average performance, but it’s also worth noting that the U.S. does very well at the top of the skill distribution as well, often winning the International Math Olympiad and coming in second only to China (a country with four times the size of the U.S. talent pool) in terms of all-time medal count. We also do well in other international olympiads.

So while the U.S. K-12 education system is not world-beating, it is of decent, above-average quality for a rich country.

U.S. education isn’t very expensive

Education quality is just one half of the cost-benefit calculation. A lot of people believe that the U.S. pours ridiculous amounts of money into K-12 education compared to other countries, but this just isn’t true. Looking at absolute spending on primary and secondary education (K-12), we see that while the U.S. spends a bit more than other rich countries, the numbers are actually quite similar:

We spend about $13,000 per student (at purchasing power parity), while the average is around $10,000. Not a huge difference.

Update: Here’s a good graph that shows the size of this difference:

And as the graph above shows, when we look at how much we spend relative to the size of our economy, it’s a different story. Relative to GDP, our education spending is only slightly above average for a rich country:

This is also true when you look at education spending as a percent of government spending.

(Update: Here’s a paper by Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok that shows that the recent growth in U.S. K-12 spending can be entirely explained by “Baumol’s Cost Disease” — in other words, as the country gets richer, it costs more to pay teachers.)

So the U.S. education system, which gets generally above-average results, costs us about average as a percent of our economy, and is only $3000 per student more expensive than average in absolute terms. This is a very different pattern than, say, health care, where the U.S. spends a much larger fraction of its GDP than other countries and achieves only middling results.

Spending more on U.S. education gets good results

But of course if we’re trying to determine whether our education system gets good value for money, we don’t just want to look at spending and results. We want to know whether the spending is necessary to achieve the results! In other words, we want to know the causal effect of public education spending on student outcomes in the U.S.

Fortunately, there are a number of econ papers that look at exactly this question. A recent example is Lafortune and Schönholzer (2022), who find very positive results for L.A. in 1999-2012:

We study school facility investments using administrative records from Los Angeles. Exploiting quasi-random variation in the timing of new facility openings and using a residential assignment instrument, we find positive impacts on test scores, attendance, and house prices. Effects are not driven by changes in class size, peers, teachers, or principals, but some evidence points toward increased facility quality. We evaluate program efficiency using implied future earnings and housing capitalization. For each dollar spent, the program generated $1.62 in household value, with about 24 percent coming directly through test score gains and 76 percent from capitalization of non-test-score amenities.

Then there’s Lafortune, Rothstein, & Schanzenbach (2016), who find large positive effects on student achievement when courts order local governments to spend more on education for low-income students:

We study the impact of post-1990 school finance reforms, during the so-called “adequacy” era, on absolute and relative spending and achievement in low-income school districts. Using an event study research design that exploits the apparent randomness of reform timing [and] representative samples from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, we find that reforms cause increases in the achievement of students in these districts, phasing in gradually over the years following the reform. The implied effect of school resources on educational achievement is large.

And, there’s Jackson, Johnson and Persico (2015), who find very similar results for the 1970s and 1980s.

In other words, the best available data indicates that when the U.S. spends more money on public schools, academic performance improves. That implies that the money we’re already spending isn’t going to waste, on average.

So let’s review the facts here. The U.S. spends an average percent of its income on public school, and achieves above-average results. And when we force ourselves to spend more, student achievement tends to improve. That strongly suggests that the U.S. is getting good bang for its buck in terms of public education.

Does that mean that every proposed government outlay on education is a good idea? Of course not. Does it mean that our education system is great and that we should just throw more money at it and forget about trying to improve the quality of American education methods? Of course not! But what it does mean is that the popular conservative narrative of U.S. public education as a wasteful money-pit is based on myth and misconception. There are plenty of things America wastes a lot of money on. Public school simply isn’t one of them.

Excellent post. I wonder how many of the critics of public education actually have children either in or who have gone through public schools K-12? Our experience was uniformly positive and both went on to graduate college with honors and go on to post-graduate education. The key is adequate financing for resources, good teachers, and small classes. Unfortunately, lots of excellent teachers are leaving the profession and that is where the crisis is right now.

The big issue is with the Title One schools that serve low income students (usually but not exclusively, those of color). Trying to understand why these students do not achieve at the same success rates is multi-factorial but whether it is family environment or something else has been difficult to tease out.

Thanks for this post. Very helpful data.

I always thought the issue with our k-12 education was high dispersion of results. That our distribution curve would show a much larger left tail than other countries. If true, then our top 80% might actually be close to number one, while our bottom 20% would be far behind.

Do comparative statistics like that exist?