Yesterday’s post was about how sanctions are affecting Russia. Today’s post is about how both sanctions and the war are affecting the world, and what we can do to mitigate the negative effects. Specifically, today I’m going to talk about food.

Remember, the purpose of sanctions — which they are accomplishing quite effectively — is to cut Russia off from trade with the rest of the world. That makes life harder on the Russians, but it also means that the rest of the world is cut off from what the Russians normally sell. On top of that, Russia’s invasion has cut Ukraine off from being able to produce and export much of what it normally produces and exports.

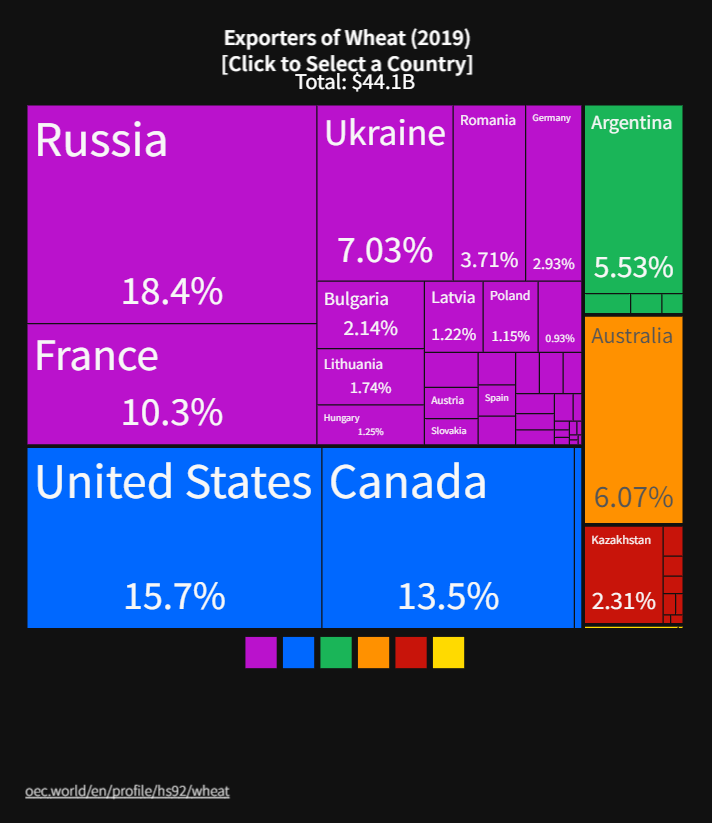

Russia and Ukraine are mainly commodity exporters. In the next post I’ll talk about energy, but today I’m going to focus on food. First let’s talk about food. Together, the two countries involved in this war export about a quarter of the world’s wheat exports:

Wheat is important because it’s a staple grain, responsible for about 20% of total human calorie consumption. So that’s a big deal. But it’s worth noting that Russia and Ukraine also export a decent chunk of the world’s barley and corn. In fact, data from the International Grains Council pegs Russia and Ukraine’s combined share of total global grains trade at 24%!

In any case, it’s no surprise that food prices are already soaring.

This is going to have big effects on the world economy, and not in a good way (at least, in the short and medium term). Standing up for Ukraine is a moral imperative and a security imperative, but there will be costs to doing that. Some people are prepared to pay these costs personally…

…but many others are simply not able to. Thus, we should try to reduce the costs as much as possible for the people who can least afford to bear them, while also taking steps to make sure our overall economy isn’t threatened.

Who is in danger from expensive wheat?

The first obvious group of people who are in danger from wheat shortages are poor countries that import lots of wheat. In fact, there are a lot of these:

Let’s take Egypt as the most worrying example. In a typical year, Egypt will import about 12 or 13 million tons of wheat, representing over half of its consumption of the grain. Most of this is imported from Russia and Ukraine. And much of that is going to get cut off. Egypt can look for other sources of wheat, but they’ll have to pay higher prices, and the search will take some time.

So Egypt could be in for serious instability. The country is known for bread riots, and it’s not the most stable of countries. Thus, we could see political instability as a knock-on effect of the Russia-Ukraine war. Nigeria is also in a bad way here — it’s not as dependent on wheat imports as Egypt is, but it’s a lot poorer, with 40% of the population living in absolute poverty.

(China and India might be exceptions here — their neutrality in the sanctions war might allow them to scoop up Russian grains at fire-sale prices. And in fact this will lessen the impact of the food shortage on the rest of the world, though it will also limit Russia’s economic punishment.)

But wheat importers are not going to be the only countries paying higher prices for wheat! That’s because the wheat market is global. When Egypt and Nigeria are forced to pay higher prices, producers in Canada and Argentina charge higher prices to domestic customers as well. So it’s no wonder that global wheat prices have shot up by about 40% since the start of the war.

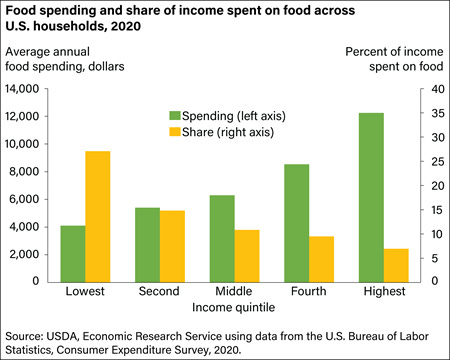

That’s going to hit poor people hard in every country. Just to take the U.S. as an example, here’s a graph of how much of their income people spend on food at various income levels:

Poor people spend more than a quarter of their income on food — and those making less than $20k a year spend a whopping 40%. So while for the rich and the middle-class, higher food prices will be mostly an annoyance, for the poor this will be devastating.

Of course, different foods are fairly substitutable, especially in a country like the U.S. with well-stocked grocery stores. Even if you’re used to eating bread every day, if the price went up by 1000% you’d learn to eat rice pretty quick. So the price of food isn’t going to go up as much as the price of wheat — we’re not looking at mass starvation here. Still, it’s something we need to worry about.

Finally, higher food prices are going to contribute to higher inflation. Much of the inflation we’ve seen in the U.S. so far has been due to a demand shock, which is now over. But expensive food, along with expensive energy (which I’ll deal with in another post), represents a negative supply shock that will push inflation up while hurting economic growth.

That’s bad, because supply shocks are very difficult to deal with. You can ease monetary policy and raise deficits to try to support employment, but this just pumps inflation up even higher. Or you can tighten monetary and fiscal policy in order to quell inflation, but this throws a bunch of people out of work. No good choices. So really, what the government does is just sit there and watch people get madder and madder.

And the really bad situation is if inflation starts an expectations spiral — a self-fulfilling prophecy where people raise prices because they expect other people to raise prices too. (This is the kind of scenario Emi Nakamura worried about in our interview, which you should check out.) Already, 5-year inflation expectations, which had been contained by the Fed’s slight turn toward hawkishness, are now surging again as a result of the war:

So if these expectations take off, the Fed will have to restore confidence by dropping the hammer, pulling a Paul Volcker, and raising interest rates to much higher levels. That will cause a recession and throw a bunch of people out of work, and might result in political instability — e.g. the return of Trump.

In other words, there’s actually quite a lot of danger from fast-rising food (and energy) prices — not just to the poor, and to poor countries like Egypt, but to the entire U.S. economy.

What can we do to ease the pain?

Which brings us to the question of what the U.S. can do to ease the pain from expensive grain. Obviously, in order to prevent mass suffering within our own populace, we can subsidize food, especially by increasing the amount we spend on SNAP. We did this once before, during the Great Recession, and we can do so again. One drawback is that this will push up food prices even more, exacerbating the inflation problem a bit. But we should probably do it anyway, because the alternative of Americans going hungry is not something we should entertain.

But buying food for our poor people is an issue of distribution, not of total production. The larger problem is that there will simply not be enough wheat getting produced in the world — in Ukraine because it’s being bombarded with Russian rockets, and in Russia because it’s not easily able to sell stuff overseas.

The U.S. might be able to step into that breach and make up some of the gap, by planting more wheat. After all, U.S. wheat production can vary by up to 20,000 tons per year, which could probably make up for all of the shortfall in Russian and Ukrainian exports. There are just two problems here. The first is the planting season: Wheat is planted either in the fall and harvested in the spring (i.e. a year in the future), or planted in the spring, which is coming up fast. So we had better do this quickly. The second is that while we can certainly devote more acreage to growing wheat, it might come at the expense of other crops, which might not help overall food prices. The U.S. no longer maintains a strategic grain stockpile, so there’s little help there either.

One solution might be to devote more land to agriculture. Over the past three decades, the U.S.’ arable land has declined from over 20% to just 17%, generally because of sprawl and other development.

It’s not clear whether a bunch of development could be torn up and converted back to farmland in a year or two, but it might be something worth looking at. We’ve done more dramatic things in war situations, after all. Of course the market will be working in this direction on its own — higher food prices will make land become more valuable as farmland than as parking lots, and might induce farmers to plant on currently fallow land, switch land from grazing to farming, etc. But there is probably a lot of regulation here, as in the energy sector, so government should look at loosening a lot of that regulation very quickly, or converting some government-owned land to farmland. If the market responds very slowly on its own (as some markets do), it may even be time for subsidies.

In any case, it’s clear that we need to be thinking of food in terms of total global supply — not just for the sake of the poor, or of poor countries, but for the sake of restraining a commodity price spiral that might make inflation uncontrollable except via recession. If that happens, then sanctions might end up being quite painful for the U.S. and our allies, as well as the Russians. Even though our country is not at war — and hopefully won’t be — the global nature of markets and the new, awesome power of sanctions mean that we need to be thinking about economics in terms of a war economy right now. Instead of simply trusting that the market will work everything out, we need to figure out policies that will boost production substantially and quickly.

Corn is the the largest crop in the US, and 40 percent of that is used for ethanol production. Maybe a prudent step would be to turn less into ethanol, and more to food stockpiles (or plant wheat)

The US has a lot of land that just lie fallow to control food prices, I believe (the government pays farmers not to farm). So I’d imagine there’s a way to buffer, though you’d probably get short-term shocks (it’s too late to plant winter wheat, for instance, which is what the wheat planted in Ukraine is).