The state of Bidenomics

Inflation is coming down and everyone has a job, but investment and wages need a boost.

I thought Biden gave a pretty good State of the Union speech this week. It was very focused on economic policy rather than foreign affairs or culture wars, which I think is a good thing; American society would be healthier right now if we were a bit more focused on abundance instead of conflict. Anyway, SOTU speeches are always a bit of a balance between trumpeting economic good news — which reflects well on the President, even though it’s only ever partially his doing — and listing policy priorities for the next year. So I thought I’d write a reaction post with a similar breakdown.

The basic story here is that Biden has been a very competent manager of the macroeconomy, but so far hasn’t been able to raise America’s low investment levels.

The Biden economy: a disinflationary boom

The U.S. economy right now is in a bit of a strange place. In 2021, it looked like we had a classic case of “overheating” — the government had spent a lot of money, the Fed had created and loaned out a lot of money, and as a result we got high employment and fast wage growth but also a nasty bout of inflation. That’s exactly what you’d expect from standard, simple, undergrad macroeconomic theory. A textbook positive demand shock. Then in early 2022, we got an oil and food price shock from the Ukraine War that added to inflation while putting a damper on economic activity; that was a textbook negative supply shock.

Then in late 2022, things got weird. The Fed (and other central banks) raised rates pretty quickly to combat inflation. As you’d expect, asset prices went down, mortgage rates went up, demand for housing went down, the yield curve inverted, and a bunch of people started predicting a recession. And, assisted by a drop in oil and gas prices, inflation moderated quite a bit:

But despite all the recession calls, there was no sign of a downturn at all in late 2022, nor in January 2023. Employment kept increasing at a steady clip, and the unemployment rate fell to lows not seen since the 1960s. There are so many job openings that the ratio of unemployed people per job opening is the lowest it’s been since we started keeping track:

And my favorite labor market indicator, the prime-age employment-population ratio — which isn’t distorted much by aging or the percent of Americans who drop out of the labor force — returned to the 80% level, a ceiling that it has only ever exceeded in the late 90s.

In other words, basically everyone who wants a job in America now has a job — or can get one pretty easily. There have been layoffs in the tech sector, but so far those are an isolated occurrence.

So the U.S. economy over the last six months or so have been pretty remarkable — a disinflationary boom, exactly the kind of thing we want to see, but which most macroeconomists think is a rare occurrence. One interpretation of this is that we’re seeing a positive supply shock — the beneficial effects of cheaper oil and gas — and that the Fed’s interest rate hikes haven’t yet had a chance to hit the economy, and when they do, there’s going to be a recession. Another interpretation is that disinflationary booms aren’t actually that hard to get — we got one in the late 2010s, after all — and that inflation is falling because the Fed convincingly signaled to businesses that it’s definitely going to tame inflation, and so businesses moderated their price hikes while still investing as normal.

Which of these theories you believe, Biden does deserve some of the credit for the goldilocks economy, but for different reasons.

If you think rate hikes are the main reason inflation is down, then it’s mostly Jerome Powell and the Fed. But rate hikes began after Biden signaled confidence in the Fed Chair by renominating him at the end of 2021. That renomination may have given Powell confidence to go ahead. And Biden could have complained about rate hikes (as Trump probably would have done), but he did not. So Biden does get some of the credit in this case. And Biden and the Dems in Congress also did do a bit of austerity in 2022, which may have helped reduce inflation as well:

If, on the other hand, you think lower energy prices are the main reason for low inflation, then Biden also gets a bit of the credit here as well. U.S. oil production was up very strongly in 2022, nearing its record high from 2019:

This is partly just a bounce-back from Covid, and partly a response to the high oil prices in the wake of the Ukraine War. But Biden did reverse his restrictive approach toward oil drilling after the war began, backing offshore drilling and resuming the leasing of federal lands for oil extraction. Biden also eased sanctions on Venezuela (a good geopolitical move as well), contributing to a rise in the country’s oil exports a deal with Chevron. He released some oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. And he also chose to look the other way as India hungrily bought Russian oil at a deep discount, allowing Russia’s oil exports to recover (though it’s getting paid less per barrel). All of these contributed to a general rise in world oil production, and the crash in prices.

U.S. natural gas production has also increased under Biden, though more slowly and steadily. And of course solar and wind continue to increase faster than fossil fuels; most of that is due to the amazing cost drops in those technologies, but Biden’s support for renewables is probably giving utilities the confidence to invest in them more.

So between rate hikes, mild austerity, and higher energy production, Biden probably does deserve a share of the credit for the fact that we’re currently seeing a decline in inflation and an employment boom at the same time. If the economy does go into recession as the result of a delayed impact of rate hikes, Biden will share a bit of the blame for that as well — but so far, there’s no sign of that happening.

Anyway, that’s the good news. The bad news is that two years of high inflation did some damage that will leave some lasting scars.

Inflation took a bite out of wages and incomes

One thing we’re learning about the macroeconomy is that many things are inherently sticky — it’s difficult to increase them much faster when the rate of inflation accelerates. Wages are a good example. In 2021, high demand for labor pushed up wages, especially at the low end. But for people in the middle class, those increases couldn’t even keep up with prices. Then in early 2022, wage increases moderated even as inflation kept going strong, and the result was that wages fell quite a bit, giving up most or all of the gains they had made back in the pandemic. Here’s real hourly compensation:

And here’s median real weekly earnings:

Median income data comes out more slowly, but it’s going to show the same thing.

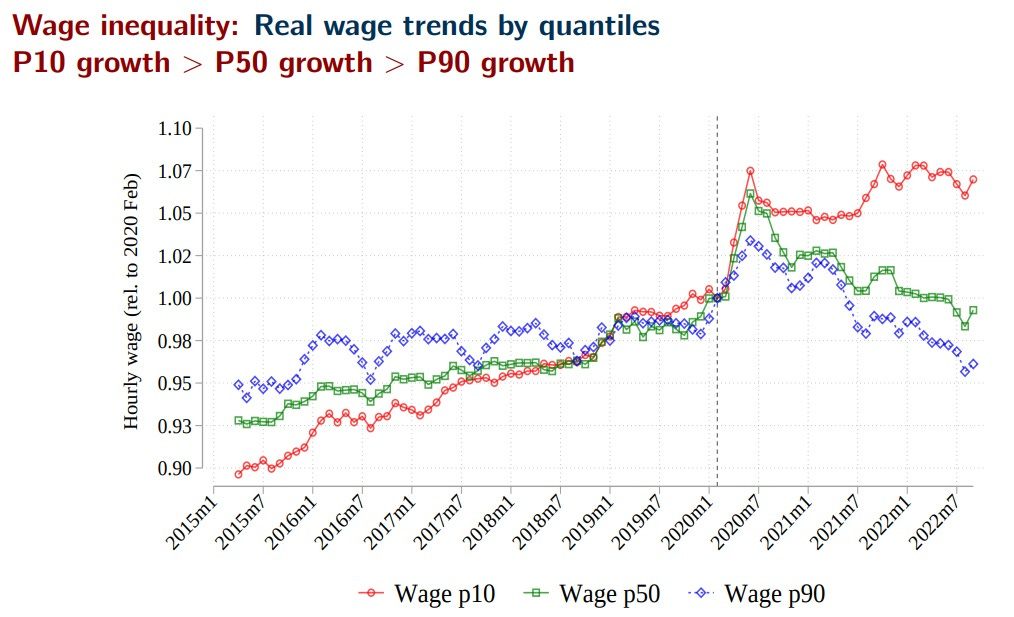

Now, the people at the very bottom of the wage distribution did manage to mostly escape this trend, which is great:

But the middle class represents a much larger share of population than the poor (pretty much by definition), and they’re the ones who vote. So they’re understandably going to be grumpy after two years of seeing their incomes fail to even tread water. And also, labor’s share of income, which rose during the pandemic, has now given up its gains:

Now, note that the wage trend has now reversed. As inflation fell in the third and fourth quarters of 2022, and overall labor demand stayed strong, wages started rising again. So that’s good news, and Biden does get some of the credit for that. But it’ll take a while for that to erase the impact of two years of falling real wages, so I wouldn’t be surprised if Americans continue to give the economy tepid ratings in the years to come.

What can Biden do to give wages and incomes a boost? Basically, there are two things he can do: increase labor demand, and increase labor’s bargaining power.

First, let’s talk about labor demand. Companies are still hiring like gangbusters, so there isn’t much more room for progress on the macro front. On the micro front, the main thing Biden can do is to pump up investment, which he did promise to do, and which I’ll talk about in the next section.

There may be more scope for increases in labor’s bargaining power — i.e., policies that help workers take home a larger share of the pie relative to owners of real estate and stocks and bonds. In his SOTU address, Biden promised to “guarantee all workers a living wage”, but most of the action on that front is likely to happen at the state level. A proposed ban on noncompetes would do more on this front, though I wouldn’t get expectations too high in terms of how much this will boost national average wages. Stepped-up antitrust action is also good, but I expect this to have more of a long-term subtle effect that will be hard to see on the charts in the next few years.

Then there’s unionization. Despite some high-profile unionizations at Starbucks, the percent of U.S. workers who are unionized reached an all-time low in 2022. Biden called for passing the PRO Act to make it easier to organize and strike, but this is unlikely to happen with Republicans controlling the House. A more promising route would be to staff federal agencies with pro-union people. There’s a sort of received folk wisdom that Ronald Reagan managed to fatally weaken unions without passing any anti-union laws, simply by staffing the government with people who were unfavorable to labor. Maybe that legend is true, maybe it isn’t, but it’s worth trying this in reverse.

In any case, I see only a modest scope for boosting wages via pro-labor policies. The most quantitatively important things the Biden administration can do on this front are probably just to keep inflation falling, try to avoid a recession, and continue its efforts to increase investment.

Investment has yet to bounce back

When I gave my grand unified theory of Bidenomics two years ago, there were three pillars: Investment, cash benefits, and job provision in care industries. Unfortunately, popular appetite for cash benefits seemed to dry up after the pandemic — Biden called for a return of the expanded Child Tax Credit, but given GOP control of the House, plus rising interest real rates that will put pressure on the federal budget, this is unlikely to happen. As for jobs provision in care industries, that was always a highly questionable idea, as shoveling money at health care and child care will just increase the excess costs in these industries that are putting a strain on the middle class.

But investment is really, really important, and Biden was absolutely right to focus on giving it a boost. Investment is crucial for long-term growth, and in the short term it boosts labor demand. That’s why Biden talks about it so much, and orients so much of his policy program around it. Here are a few excerpts from his SOTU address:

[W]e came together to pass the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act…With this new law, we will create hundreds of thousands of new jobs across the country. That’s going to come from companies that have announced more than $300 billion in investments in American manufacturing in the last two years…Outside of Columbus, Ohio, Intel is building semiconductor factories on a thousand acres…

Now we’re coming back because we came together to pass the bipartisan infrastructure law, the largest investment in infrastructure since President Eisenhower’s interstate highway system…

[T]he Inflation Reduction Act is also the most significant investment ever to tackle the climate crisis…

I will make no apologies that we are investing to make America strong. Investing in American innovation, in industries that will define the future, and that China’s government is intent on dominating.

And so on.

All of these policies are great, and Biden is thinking along the right lines here. But it’s important to realize that so far, Biden’s term in office has not represented an investment boom at all.

Here is gross domestic investment by private business, the federal government (green line), and state and local governments (red line):

As you can see, private investment rose in 2021 and then flatlined in 2022, while government investment increased extremely slowly and wasn’t really affected by the pandemic.

But that chart was in dollars — in other words, it’s a chart of nominal spending. Now here’s what it looks like when we adjust for inflation:

The U.S. is clearly not experiencing any kind of a revival in either private or government investment. The employment boom is due to increased consumption and exports, not to businesses or the government buying new capital.

Now, this doesn’t mean Biden’s investment-boosting policies have failed; many of the signature initiatives he mentioned haven’t really had time to work yet. The IRA and the CHIPS Act both passed in August, and the smaller Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed in late 2021. Many projects funded by these programs are not “shovel-ready”, as the saying goes; their impact will be felt over the course of multiple years. It took three years for government investment as a share of GDP to peak after the passage of the Interstate Highway Act in 1956, for example.

But I’m concerned that many of the investments won’t actually be made at all — or not within a reasonable time frame. For example, the grid interconnection queue was already filled up with renewable energy projects by the end of 2021, but these haven’t been getting actually built, since U.S. law and administrative and regulatory systems are very effective at preventing development at the local level. NEPA is part of the problem here, but permitting reform — which Biden couldn’t even get passed — isn’t a silver bullet. The U.S. simply got used to the idea that the built environment was pretty much already built, and that future construction projects would be minor efforts that we could afford to delay.

In addition to delay, there’s the issue of America’s ruinously high construction costs. Transit projects, including both roads and trains, cost much more in the U.S. than in other countries, and these costs have exploded in recent decades. Costs feed into delays, and delays feed into costs. This is just as true for the private sector; unsurprisingly, the TSMC factory that Biden is trumpeting in the U.S. is hitting major delays because navigating local rules is proving more expensive than expected. Of course, factories and roads and trains and power lines that never get built don’t actually boost labor demand, because the workers don’t get hired.

The reason America is not investing is because our system is set up to stymie investment. We are a country that has embraced physical stasis since the 1970s, and we suddenly find ourselves in a situation in which we cannot afford to stand still any longer.

If Biden really wants to boost investment, both at the government and private level, he needs to tackle this basic problem, not just spend more money. Barriers to the development of infrastructure, clean energy, and factories must be rooted out not just at the federal government, but at every level of government. To use a phrase that’s trendy these days, we need a “whole-of-government approach” to battering down project delays and excess costs. If we do not do that, all of the investment numbers Biden and his people cite will be just that — numbers on a sheet of paper.

So far there is little sense that the administration appreciates the gravity of the problem. Biden’s “Buy American” plan — to source infrastructure construction materials only from the U.S. — won’t increase costs by that much, since materials are not a big source of cost overruns. But it demonstrates a lack of concern for America’s ruinous cost issue.

Biden has been a competent manager of the macroeconomy so far. And the policies he has passed are good ideas that, if actually implemented, have the potential to transform the American economy in a positive direction. But unless the administration can actually turn the numbers that it has written on paper into actual real existing power plants and transmission lines and factories and roads and trains, then Bidenomics will not have changed the basic trajectory of the American economy.

The task of the next two years should be to make it easier for America to build things.

Fine article.

I think the daily press have been suckers for economics which get both current price increases and future prospects wrong.

As your article says, Covid and Ukraine are salient right now, so we have a price bump and some stringencies. We are not facing Armageddon because the price of a loaf of bread just went up a quarter.

Very good review.