The reverse OPEC maneuver

Pricing power in the oil industry is shifting, and will shift more.

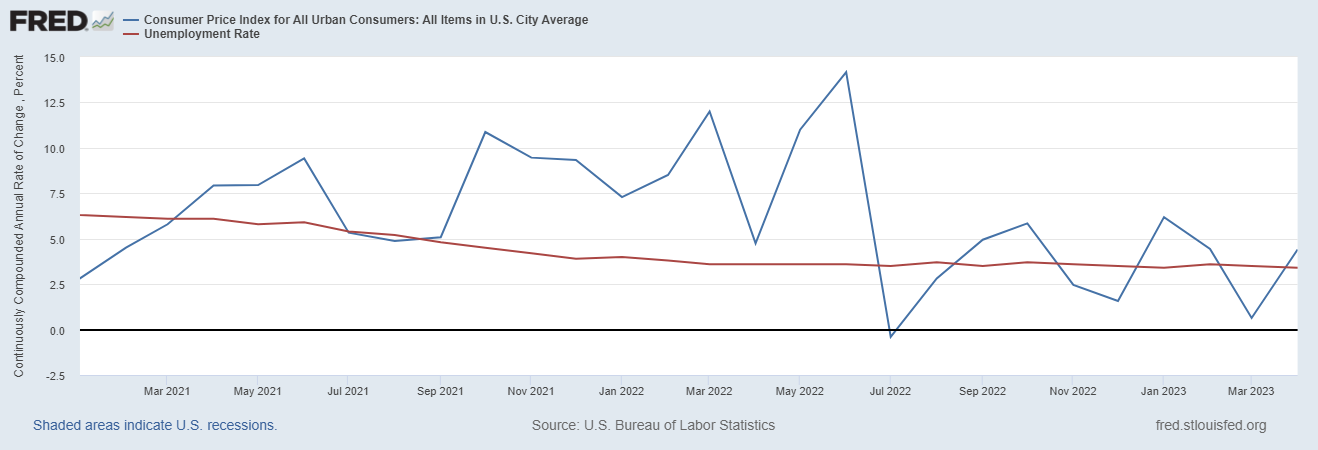

The U.S. economy has been doing very well over the past year. Since summer 2022, unemployment has continued to fall, even as inflation has dropped from the 8-9% range to maybe 4-5%.

You can look at other measures of prices and the labor market, but they’ll tell the same story.

When you see inflation go down and the real economy continue to do well, you should probably look around for a positive supply shock — something that allows the economy to produce lots of things more cheaply. And when you look for a positive supply shock, you should usually start by looking at whether energy has gotten cheaper, since everything requires energy to produce, and energy prices tend to change very quickly. And indeed, when we look at oil prices, we see that there was a big and sustained drop right in the summer of 2022, when everything started to go right for the U.S. economy:

There are a number of reasons for the price drop — a fall in demand from China due to its economic slowdown, a recovery in oil production to near-pre-pandemic levels, Biden’s use of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, and so on. But one factor is just what economists call “market structure” — a change in the nature of competition in the oil industry.

Basic background: Cartels, OPEC, and defections

Most people have heard of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC — a cartel of oil-producing countries that tries to manipulate the global supply of oil in order to control the price and maximize their own profits. In 2016, OPEC added some more members — most importantly Russia — in order to create “OPEC+”.

Anyway, the very basic version of how OPEC or any cartel is supposed to work is pretty simple, and most people already grasp it. In a normal competitive market, different producers outcompete each other by producing more and cutting prices, thus benefitting the consumer at the expensive of all the producers’ profits. In a monopoly market, the monopolist curbs production in order to drive up prices, thus maximizing its own profits. The idea of OPEC is that by all getting together and agreeing to cut production, the oil producing countries can act like a monopoly, jacking up the global oil price to increase their profits at the expense of oil consuming countries.

In the past, this tactic has been very effective. In 1973, OPEC plus a couple of other countries famously cut production and raised prices, precipitating the first oil crisis. Officially this was a geopolitical response to the West’s support for Israel in the Yom Kippur War, but really it was all about raising oil exporters’ profits. Which it did. Oil prices stayed high throughout the 70s, spiking yet again during the Iranian revolution at the end of the decade (the second oil crisis).

The reality of cartels, though, is that they’re very difficult to maintain. Each member has at least some incentive to defect — to break from the group and sell more oil to the consumer countries, thus increasing its own total profits while lowering the price a bit. The higher the price goes, the greater the incentive to defect. Cartels need some kind of enforcement mechanism to prevent this behavior. Traditionally, in OPEC, the enforcement mechanism was thought to depend on the power of Saudi Arabia, the biggest producer in the cartel. If other countries produced more than their allotted quotas, the Saudis would turn on the taps and send the oil price crashing, thus tanking the profits of the other OPEC countries. Since Saudi Arabia is one of the lowest-cost producers in the world, this would end up hurting other countries more than it would hurt the Saudis — thus, it was a credible threat.

In fact, this is exactly what happened in the early 1980s. The high prices of the 70s had prompted a bunch of countries outside OPEC to go discover new sources of oil. So as a result, new non-OPEC supply was starting to come online, and the oil price had begun to drop. Seeing the writing on the wall and deciding that they needed to cash out in the short term by selling more oil, many OPEC members defected. Saudi Arabia then punished them by flooding the market with oil, causing a glut and sending prices crashing. This gave the economies of developed countries a major boost in the 80s and 90s. Only in the 2000s did oil prices rise again, driven by increased Chinese demand, the Iraq War, and other factors. Then in 2008 the Saudis themselves defected from OPEC, which — along with the advent of U.S. fracking and increased production — sent oil prices lower again in the mid-2010s.

That’s what prompted the creation of OPEC+ in 2016. By adding Russia and some other countries to the cartel, the hope was that OPEC could solidify its control over global oil supply, which would thus reduce the incentive to defect. This worked better in theory than in practice, though, and OPEC+ continued to see defections and disagreements.

The Ukraine War, price caps, and the possibility of a Reverse OPEC

The Ukraine War changed at least two big things for the structure of the global oil market. First, Russia needs to fund its war machine, meaning it needs as much money as it can get, right now — especially because of sanctions. In normal times Russia might cooperate with OPEC to cut production in order to raise prices out of consideration of the long-term benefits — by maintaining the cartel, they might be able to keep prices and profit margins high for a very long time. But because of the war, Russia can’t afford to think about the long term; it needs money immediately.

In econ-speak, short-term necessity gives Russia a high discount rate, which increases the likelihood of defection. Remember that OPEC’s traditional enforcement mechanism is that countries want to curb their output in order to maintain a good long-term relationship with Saudi Arabia, so that the Saudis don’t punish them by glutting the market. But Russia can’t afford to think long-term right now, so the enforcement mechanism can’t work on Russia.

Thus, despite promising other OPEC+ countries that it would cut production to help them maintain their profits, Russia has boosted its own oil output as much as it can, back to the levels of before the invasion. That has helped glut the oil market and send prices crashing worldwide.

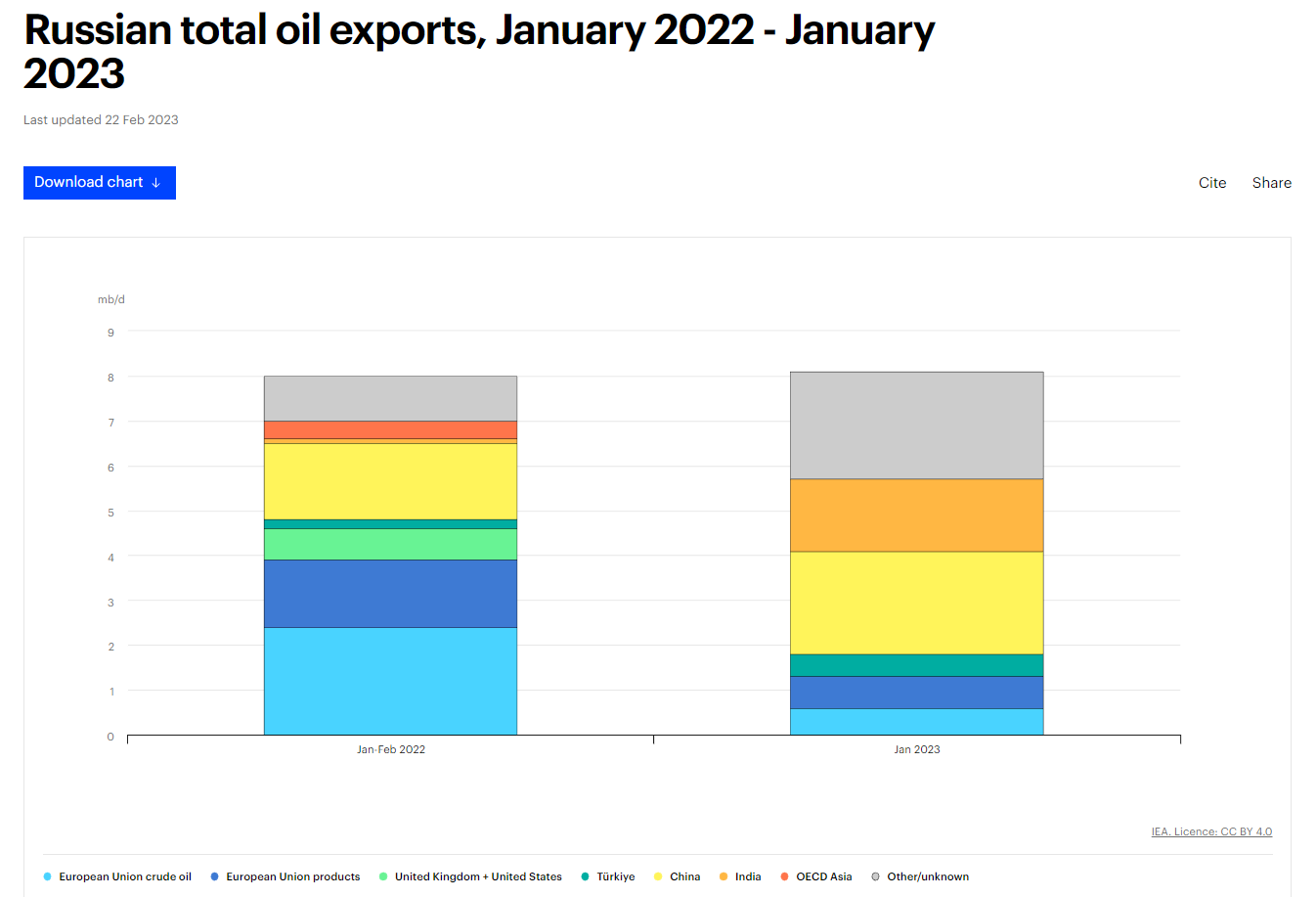

Second, sanctions have curbed Western demand for Russian oil, which has forced Russia to rely more on non-Western buyers who haven’t joined the sanctions. About half of its oil now goes to China and India:

In terms of seaborne oil, China and India now account for 90% of Russia’s exports, with India taking the biggest share.

The dominance of these two countries as buyers of Russian oil, combined with Russia’s need to get as much revenue as it can right away, mean that Russia is having to sell to its two main buyers at a steep discount. Urals crude, the price of Russian oil, is at around $57 per barrel, which is about $15-$18 lower than the prices being paid by the West. That’s one reason Russia’s oil revenue is down by 27% from before the war even though its production is now higher.

Another thing Russia’s opponents have done is to impose a price cap of $60 per barrel on Russian oil. This has intensified Russian reliance on India and China, because it means that if Russia wants to sell oil for more than $60, it can’t sell to the G7. If you like supply-and-demand curves, well, here’s what that looks like:

I drew Russian supply as a nearly-straight-up-and-down line — i.e., very inelastic — because it needs to produce as much as it can in order to keep funding its war. Thus, the effect of the cap, like the effect of other sanctions, is just to drive down the price Russia gets.

Meanwhile, that glut of Russian oil is making it hard for OPEC to maintain its own output quotas. Since war has effectively forced Russia to defect from OPEC+, other countries — notably in Africa — want to defect as well. Saudi Arabia is trying to corral them into making output cuts to keep prices high, but they’re not listening. This is from the WSJ:

OPEC members huddled together for hours in Vienna to hash out a deal in what turned out to be a fiery exchange…Saudi Arabia was pushing some members to cut output but faced stiff resistance, especially from some African producers…

Sunday’s meeting also came amid growing tensions between Saudi Arabia and Russia—two of the world’s biggest oil producers—over previously agreed-upon production cuts. Russia keeps pumping huge volumes of cheaper crude into the market, undermining Saudi Arabia’s efforts to bolster energy prices.

Saudi Arabia is currently cutting output all on its own, in an attempt to stop prices from sliding more. That approach will fail; the Saudis aren’t a one-country cartel, and without the cooperation of Africa and Russia, their output cuts will just reduce their own revenue. Whether the Saudis eventually decide to turn around and flood the market with cheap oil, as they did in 1985, is an open question.

In other words, the combination of the $60 price cap and the China-India duopsony effectively mean that the world has formed a buyer’s cartel with regards to Russian oil — sort of an anti-OPEC. The G7 are doing it for moral reasons while China and India are simply taking advantage of the situation to get a discount, but it basically amounts to the same thing.

EVs and the sunset of oil

Some have wondered whether the current “reverse OPEC” arrangement might morph into something more permanent. China and India have been discussing the idea of a buyers’ cartel for years now, and G7 price caps might provide a mechanism for informally joining forces with the developed democracies — effectively two cartels that cooperate in ad hoc situations. Price caps could potentially be used against Iran in the future, too. Who knows; someday they might even take on Saudi Arabia. If that happened, the power dynamic in the oil market might permanently flip, with buyers rather than sellers now in the drivers’ seat.

There’s another big development at work here too — the global shift to electric vehicles, which now looks unstoppable. That will reduce global oil consumption by 5 million barrels a day by the end of the decade, according to the IEA, or about 5% of current levels. That’s not enough by itself to put oil exporters out of business, but it means that OPEC countries now face a future of demand that just keeps shrinking year after year. In that kind of environment, as we saw in the early 80s, there’s a stronger incentive for producers to defect — to sell as much oil as possible today, while prices are still high, in the knowledge that things will only get worse from here.

So OPEC’s power could be permanently broken, just as a new de facto buyers’ cartel (or a pair of such cartels) starts to form. That would reverse the market power dynamic we’ve seen since 1973, and lead to a new age of cheap oil. That wouldn’t be such great news for the climate, since an end to OPEC would slow down the EV transition a bit. But for the economies of the U.S., Europe, and Asia, it would be a long-term shot in the arm.

Currently Russia is undercutting Saudi pricing on petroleum sales to Asia (China and India) which also is the largest future market for oil and gas. Russia is selling its oil so cheaply that even the Saudis are buying Russian petroleum on the cheap and selling theirs at full market price sanction-free.

As the petroleum market tightens with the shift to renewable energy sources and electric vehicles, the Saudis will need to reclaim their Asian markets from Russia. This will involve a price war similar to the one that collapsed the USSR. China and India are transactional allies of Russia and will go with the sweetest deal. This is why China has been courting both Saudi Arabia and Iran recently. Russia is over extended and China is already mobilizing its 'Plan B' to keep the pipelines full if Russia collapses again.

Obviously this article is primarily about the economic forces at play, but it's really not a coincidence that at the same time this is happening, KSA is spending gobsmacking amounts of money on sportswashing, preparing itself to have some external support when these anti-OPECs start to turn the screws.