The NYT article on MMT is really bad

The fringe ideology's star is falling, and puff pieces will not resuscitate it

The New York Times just came out with a big glowing writeup of MMT, entitled “Time for a Victory Lap*”. This article aroused the anger of just about every macroeconomist on Twitter, and with good reason — it demonstrates very little understanding of the issues at play or the state of the policy debate, and it rhetorically elevates a fringe ideology to a position of importance and centrality that it neither occupies nor deserves.

Please consult macroeconomists before writing about MMT!

The NYT article on MMT, written by Jeanna Smialek, is mostly a puff piece about Stephanie Kelton, MMT’s most well-known proponent. In glowing tones, it describes Kelton’s clothes, her office, her house, her neighborhood, her blog, her manner of speaking, her personal story, and so on, calling her “the star architect of a movement that is on something of a victory lap”. Very little is written about the background of the macroeconomic policy debate, and what does appear is highly questionable:

In economics, there’s a school of thought sometimes called “freshwater.” It’s the set of ideas that became popular at inland universities in the 1970s, when they began to embrace rational markets and limited government intervention to fight recessions. There’s also “saltwater” thinking, an updated version of Keynesianism that argues that the government occasionally needs to jump-start the economy. It has traditionally been championed in the Ivy League and other top-ranked schools on the coasts.

You might call the school of thought Ms. Kelton is popularizing, from a bay that feeds into the East River, brackish economics.

The brief description of freshwater and saltwater economics is fine, but to describe MMT as being “brackish” — i.e., some sort of fusion of freshwater and saltwater, or a middle ground between the two — is absurd. MMT doesn’t take its inspirations from either of those schools of thought — its ideas (to the extent that such exist) are rooted in things like functional finance and Post-Keynesian macroeconomics, which split off from the mainstream long before it divided into freshwater and saltwater. MMT doesn’t even use formalized mathematical models of the economy like freshwater and saltwater econ do (or like Post-Keynesian macro does), so it’s pretty impossible to compare these schools of thought. In terms of policy prescriptions, MMT is far, far more sanguine about government borrowing than either freshwater or saltwater.

The article then demonstrates that it has little notion of what separates MMT from mainstream thinking:

M.M.T. theorists argue that society should feel capable of spending to achieve its goals to the extent that there are resources available to fulfill them. Deficit spending need not be constrained to recessions, even theoretically. Want to build a road? No problem, so long as you have asphalt and construction workers. Want to feed children free lunches? Also not a problem, so long as you have the food and the cafeteria workers.

In fact, this is also a feature of all freshwater and saltwater models of the economy. Those models deal only in real variables — asphalt and construction workers and food and cafeteria workers and so on. In fact, those models’ lack of attention to financial constraints of any kind is exactly why they failed to predict the Great Recession!

These passages — and the lack of any other engagement with non-MMT theories, research, or ideas — make it clear that Smialek’s main source on all of these topics was Kelton herself. She does briefly quote Jason Furman, a Harvard economist and former CEA chair under Obama:

“M.M.T. was already pretty marginal,” said Jason Furman, a Harvard economist, noting that, in his view, most policymakers and prominent academics ignored it already. Even if policy in the pandemic effectively embraced the idea that you do not have to pay for your spending, that idea, he said, was also Keynesian.

And the M.M.T crowd, while dismissing the Fed’s role, has not come up with a clear and obviously workable idea for how to stem inflation, he argued, adding, “If you were open-minded, this would discredit it still further.”

But even though Furman notes that Kelton did a bad job of characterizing the difference between MMT and Keynesian thinking, the NYT writer doesn’t follow up on this at all; she makes no effort to clarify where MMT actually does differ from other forms of economic thought. Nor does she quote any other macroeconomists.

This is important because any attempt to engage with the actual substance of MMT quickly finds that such substance is curiously lacking. MMT proponents almost always refuse to specify exactly how they think the economy works. They offer a package of policy prescriptions, but these prescriptions can only be learned by consulting the MMT proponents themselves. There is no model here — no set of equations or definite formal statements that a layperson could use to generate their own MMT policy prescriptions without appealing directly to the gurus.

Every economist who has attempted to engage seriously with MMT literature has concluded the same. When Drumetz Françoise and Pfister Christian of the Banque de France read Kelton’s book and tried to comprehend the essence of MMT, they concluded:

Overall, it appears that MMT is based on an outdated approach to economics and that the meaning of MMT is a more that of a political manifesto than of a genuine economic theory…As Hartley (2020) notes, MMT “is not a falsifiable scientific theory: it is rather a political and moral statement by those who believe in the righteousness – and affordability – of unlimited government spending to achieve progressive ends”.

And in a working paper analyzing MMT, economist Giacomo Rondina writes:

I believe that the big merit of MMT scholars is to have opened a large crack in the “how do we pay for it” line of defense to economic policies by pushing a liberating narrative that promises a society where well-being, abundance, and social justice are finally possible for everyone. I admire and applaud their effort.

At the same time, my reading of the MMT academic literature suggests that MMT has not yet provided a fully coherent theory of the macroeconomics of government intervention that can persuade genuinely interested mainstream academic economists and policymakers. To my knowledge, there are no scholarly works that offer clear assumptions and explicit results of when the deficit of the public sector (surplus of the private sector) can be welfare improving, taking into account the behavioral response of the economic actors involved, and specifying a transparent mechanism of price determination. As a consequence, many macroeconomic practitioners “peeking under the hood” (cit.) of MMT cannot help but feel a sense of frustration in understanding how exactly the engine is supposed to work. I believe this has limited the ability to find a common ground on which constructive progress can be made.

Meanwhile, Thomas Palley, a Post-Keynesian macroeconomist, has for years been writing exasperated and highly detailed critiques of MMT literature. If you lean toward the heterodox side of the fence, and would like to read some critical analysis of MMT that doesn’t rely on any sort of orthodox modeling or assumptions, I strongly recommend reading Palley’s papers.

Most of MMT’s critics point out their failure to write down a concrete description of how they think the economy actually works. On the very few occasions that they do, the results have raised serious doubts about whether MMT proponents even understand the concepts they talk about. For example, back in 2019 I found an MMT paper that actually had a formal model in it, and when I examined it closely, I found that A) the model’s assumptions were fairly absurd, and B) its policy prescriptions were explicitly based on the forced labor of colonial Africa. Meanwhile, when Scott Sumner read through MMT literature, he noticed that their definition of “saving” was completely different from the standard definition, and in fact made little sense.

So maybe MMT people don’t write down models of the economy because they can’t. Because as Françoise, Christian, Rondina, Palley, and others have concluded, MMT is not a theory of how the economy works, but rather a set of political memes to push for more deficit spending.

Had Smialek looked more deeply into MMT instead of taking her info on it directly from its leading proponent, she would probably have discovered this!

MMT and inflation

Smialek’s NYT piece does leave room for a very mild, hesitant skepticism of MMT (hence the asterisk in the title). This isn’t based on any of the fundamental issues described above, but on the uneasy sense that MMT has little to say about inflation:

The bad news: Some economists blame big spending in the pandemic for today’s rapid price increases. The government will release fresh Consumer Price Index data this week, and it is expected to show inflation running at its fastest pace since 1982…

[A]s inflation surges, the headlines declaring that the theory had “won” need some caveats…Many economists, both mainstream and M.M.T. ones, did not think that the March 2021 package would be inflationary…

In Washington, the [MMT] suite of ideas has clearly been dealt a setback. Deficit concerns have returned…[There are q]uestions like: “Did Congress ‘experiment’ with MMT, and does the run-up in inflation mean that MMT has ‘failed’?

But in the end, the NYT article dismisses those concerns, based on nothing more than Stephanie Kelton’s personal force of conviction:

Has the M.M.T. experiment failed? “The answer,” it declares, in bold face, “is an unequivocal no.”

Why let someone else shape your narrative, when you could shape your own?

The real question, in my mind, is why the NYT let MMT’s advocates do all the shaping of their own narrative.

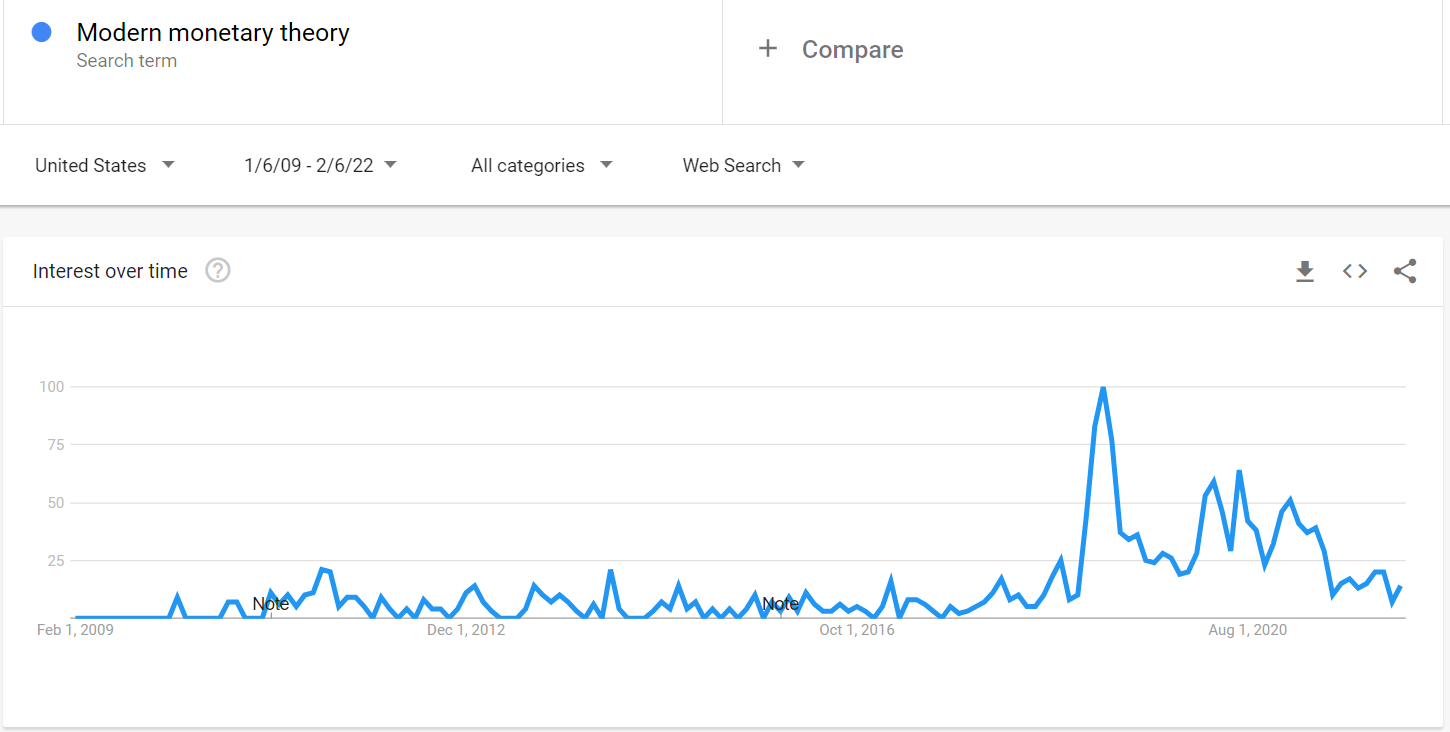

The fact is, MMT is a meme whose star is already falling, and inflation is almost certainly the reason why. Google searches for the idea have cratered since June 2021:

Interest surged in 2019 when the writers of the original Green New Deal used MMT as their justification for not finding ways to pay for all the new spending, then fell as econ writers from across the political spectrum — including some hardcore socialists closely aligned to the Bernie Sanders movement — rose up to caution the world against the idea. Sanders had probably already parted ways with Kelton, and after this fracas, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and her allies stopped championing the idea as well.

But the econ writers’ warnings about the potential harms of MMT — that unrestrained deficit spending could cause hyperinflation — seemed a bit far-fetched at the time, since inflation was still quite low, and had remained low despite the stimulus of 2009 and various rounds of tax cuts. Interest resurged in 2020 as Covid relief spending exploded.

Then in the spring of 2021, inflation started to rise to levels not seen for decades, and by summer it seemed clear that it wasn’t just a blip.

That rise in inflation was exacerbated by supply chain inefficiencies and disruptions, but it was almost certainly propelled to some extent by Covid relief spending and the Fed’s extremely loose monetary policy. That was a reminder that aggregate demand has a limit — that you can only boost the economy with fiscal and monetary policy so much before costs start to appear. (Those costs, as any orthodox macro theory will tell you, are due not to any issue with government financing, but to the economy’s real constraints — the limits of real resources available.)

To most people, who correctly recognize that MMT is a set of political memes to push for more deficit spending, this inflation represented a reason to be less enthusiastic about MMT itself — we finally seemed to have reached our limits. Proponents of austerity and/or tighter monetary policy began to use “MMT” as shorthand for the policies the U.S. had already undertaken.

Of course, MMT proponents themselves didn’t see things that way. They did indeed attempt to take a victory lap. But this is always what they were going to do, no matter what! If Covid relief efforts hadn’t been sufficient to produce inflation, they would have also taken a victory lap. If interest rates on U.S. government bonds had risen, causing a contraction in economic activity, they would have taken a victory lap, arguing that the Fed should have used monetary policy to lower those interest rates. Even if the U.S. government had defaulted on its sovereign debt, throwing the economy into chaos, the MMT people would have taken a victory lap, arguing that this was a mistake.

In other words, there was no conceivable state of the Universe in which MMT people would not have taken a victory lap. They always take victory laps, all day long, rain or shine. When you have an unfalsifiable meme complex instead of a concrete and falsifiable theory, it’s easy to claim that your ideas cannot fail, they can only be failed.

But to the rest of the world, inflation gave a reason to be skeptical of MMT’s constant advocacy of yet more deficit spending. So their star began to dim. This NYT puff piece represents the MMT gang’s efforts to jump-start a revival of their falling fortunes. The attempt seems likely to fail. As Jason Furman notes in a recent thread, MMT’s failure to persuade even the leftiest U.S. politicians to accede to its tenets should tell us something about its future prospects:

So ultimately, neither puff pieces in major newspapers nor fierce Twitter battles will have much of an effect on actual policy. MMT people will continue to find new starry-eyed advocates to dazzle with words that sort of sound like economic theory, and this will lead to brief outbursts of social media rage, followed by frenzied and bitter assaults from MMT’s small but highly active social media army. And then eventually most of the new enthusiasts will realize that there’s no “there” there — that the problems they had thought were mere asterisks were actually the whole thing — and they’ll quietly drift away.

As a coda, though, I should point out that the really scary threat to U.S. macroeconomic policy comes not from MMT — nor, at the moment, from the return of austerity. It’s from the people advocating price controls. Some decided non-fringe economists — James K. Galbraith of UT Austin, Todd Tucker of the Roosevelt Institute, and J.W. Mason & Lauren Melodia of the Roosevelt Institute, to name just four — have advocated adding price controls to our inflation-fighting toolkit, despite the fact that both theory and history offer us little reason to think the tool would be effective. In fact, a shift from a regime of demand management based on monetary and fiscal policy to one based on price controls and direct intervention in industry could spark runaway inflation as it did under Chavez and Maduro in Venezuela. The Biden administration hasn’t gone for price controls yet, but it has attempted to blame inflation on powerful companies, suggesting that Biden’s people might be thinking along these lines.

So while arguing about MMT might be cathartic, we shouldn’t let it distract us from the need to resist other bad macro ideas that actually do have a chance of working their way into the halls of power.

Update: After reading this post, someone on Twitter asked me whether I think the size of government debt matters at all. Yes, it matters, for one reason. That reason is called fiscal dominance. When the stock of government debt is high, monetary policy becomes constrained, because any attempt by the central bank to raise interest rates in order to control inflation will raise the amount of interest the fiscal authority (in our case, Congress) is required to pay on the portion of the national debt that it rolls over. Paying much higher interest costs through fiscal means requires austerity, which is very bad for the economy. An alternative policy is for the government to default, which is also very bad for the economy. Thus, having a large accumulation of government debt ties the hands of the central bank, which makes it less able to respond to inflation when needed. David Andolfatto explains this in a recent essay for the St. Louis Fed. Anyway, things like this show why it’s important to have a theory of the economy that you can actually write down on a piece of paper. Andolfatto has such a theory, which is why he can show you how fiscal dominance is a problem. With MMT people, who never write down their theory in clear and unambiguous terms, you just have to take their word for everything.

Update 2: Jeanna Smialek, the author of the NYT piece, wrote a response to this post on Twitter:

But I think this is the whole problem. You can’t write seriously about an idea like MMT without evaluating that idea to some extent. Imagine writing a hagiographic, hero’s-journey piece about a prominent antivaxxer, without even bothering to call up some virologists and ask whether vaccines really work. Writing such a piece would leave the world badly misinformed. Yet that’s exactly what was done with this MMT piece — it told the narrative of how MMT has interfaced with the world, without doing any serious reporting on whether MMT has any substantive merit. And I think that has left NYT readers misinformed. (BTW the original version of this post had a typo in Jeanna’s name, for which I apologize.)

Update 3: Axios has an article alleging that I criticized MMT because Kelton is a woman, and seemingly implying that I was also involved in recent criticisms of Lisa Cook’s candidacy for the Fed Board of governors. In fact, I just released a podcast episode (with Brad DeLong) strongly defending the very excellent Lisa Cook against all of her detractors. So I hope they update their article soon to make that explicit. And the reason I criticized MMT — most of whose leading proponents are actually white men, e.g. L. Randall Wray, Warren Mosler, Bill Mitchell, Nathan Tankus, Rohan Grey, and so on — was not because Kelton is a woman, it’s because MMT itself is an untestable pseudo-theory jockeying for political influence that it doesn’t deserve. In fact, econ does have a sexism problem, as I have written about many, many, many, many times. But I guarantee you that giving MMT undue credence and power is not the solution to that problem. Elevating real, serious, highly qualified woman economists like Lisa Cook is one part of the solution.

One thing internet MMT people are strangely into is job guarantees, which seems to be a right-wing workfare idea rebranded as left-wing using some New Deal language. Some things I've noticed are:

- the adherents are from older demographics (judging by writing style), possibly converts from alt-right or resistance lib-ism, but no idea where they're learning about this…

- they have a rhetorical trick where they call it "giving everyone well-paying $15/hr jobs" - but this assumes the $15/hr minimum wage world, so of course it actually means "giving everyone minimum-wage jobs".

- they get really mad at you if you propose UBI/CTC instead (so people can do childcare or search for better jobs) and say you're going to cause mass unemployment. This seems to come from believing that unemployment is caused by resume gaps and not knowing how to behave on the job, so needing practice at it first. Guess that's common folk wisdom though.

It is important to distinguish between what is trivially right about MMT, which is that, in a fiat currency system with a floating exchange rate, the real constraint on deficit spending is inflation, and what is speculative and probably wrong, which is that inflation can be controlled by a job guarantee setting a wage anchor. As Martin Wolf said, what is right about MMT is not new (it is functional finance) and what is new about MMT is probably wrong. I do not understand why so many critiques ignore this critical distinction. Is it because they genuinely do not understand how fiat currency systems work? Is it because they are trying to maintain the myth that governments really have to raise money by tax or borrowing BEFORE they spend it? The latter is a self-imposed legal obligation. Laws can be changed.