The new industrial policy, explained

We're starting to learn what replaces the old free-trade consensus.

For about a decade now, Americans have known that the free-trade consensus that prevailed during the 1990s and 2000s wasn’t really working. There were basically two reasons for that, and they both had to do with China. First, the speed and disruptiveness of China’s entry into the global trading system destroyed the career trajectories of large numbers of American workers and hurt the economies of whole regions. Second, U.S. complacency about the trajectory of Chinese politics, combined with a massive campaign of technological espionage, hastened and encouraged the rise of a new, hostile superpower. By the mid-2010s, only economists thought that free trade was still an unquestioned good, and the country wasn’t listening to economists the way it used to.

The first policymaker to really go against the consensus was Donald Trump, because if there’s one thing Trump excels at, it’s violating norms. His regime of tariffs, investment restrictions, and export controls, and his bumbling attempts to jawbone companies into putting factories in the U.S., constituted the first halting, haphazard attempt to formulate some kind of alternative to the orthodoxy of the previous decades. The result was pretty mixed. Overall, the outcomes were negative for the U.S., which was hurt by the tariffs and which didn’t see a reshoring boom. But China was hurt more, both by the tariffs and by the export controls. As industrial policy, Trump’s policies failed; as economic warfare, they showed promising signs of effectiveness.

This dichotomy pretty neatly explains which parts of Trump’s agenda Biden kept. Investment restrictions and most tariffs stayed, and export controls were massively expanded. But in place of Trump’s hapless rhetoric-based attempts to put factories back on American soil, the Biden administration opened its purse strings, with the CHIPS Act for semiconductors and the Inflation Reduction Act for green energy.

The really important thing about Biden’s policies, though, is that they don’t even gesture halfheartedly in the direction of “free trade”. The idea of free trade never carried much water with the general public; now, it carries essentially no water with the political class or the intellectual class either. The free-trade consensus is dead as a doornail.

We don’t know exactly what will replace the free-trade consensus yet, but we’re starting to get a pretty good idea of what the Biden administration wants the next paradigm to be. Members of the Biden administration have made a number of important speeches about the new industrial policy, including a speech last October by former NEC Director Brian Deese about America’s “new industrial strategy”, a speech in February by Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo about the CHIPS Act and a speech in April by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen about China policy. But I think the most comprehensive statement yet was the recent speech by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at the Brookings Institution. If you want to understand why U.S. policy has changed, what the current administration thinks the new objectives are, and what methods they believe will achieve those objectives, I recommend starting with this speech.

Here are a few key excerpts:

When President Biden came into office more than two years ago, the country faced, from our perspective, four fundamental challenges…First, America’s industrial base had been hollowed out…The second challenge we faced was adapting to a new environment defined by geopolitical and security competition…The third challenge we faced was an accelerating climate crisis…Finally, we faced the challenge of inequality and its damage to democracy…

When President Biden came to office, he knew the solution to each of these challenges was to restore an economic mentality that champions building. And that is the core of our economic approach. To build. To build capacity, to build resilience, to build inclusiveness, at home and with partners abroad. The capacity to produce and innovate, and to deliver public goods like strong physical and digital infrastructure and clean energy at scale. The resilience to withstand natural disasters and geopolitical shocks. And the inclusiveness to ensure a strong, vibrant American middle class and greater opportunity for working people around the world.

All of that is part of what we have called a foreign policy for the middle class. (emphasis mine)

I’ve highlighted the phrase “a foreign policy for the middle class” because I think that really captures the essence of what the administration is trying to do. Biden’s people believe that the same set of policies that will build up American strength vis-a-vis China will also work against domestic inequality and help restore the American middle class. That doesn’t mean they see China as the root of America’s economic ills, as Trump did — instead, it means they think they can kill two birds with one stone. Three birds, if you count climate change.

What are the chances that the same policies that would strengthen the U.S. in the international arena would also boost the middle class at home? In fact, I do think there’s a good precedent for this: World War 2. The massive military manufacturing boom unleashed to fight that war, as well as the advent of science and technology policy, ended up boosting the power of labor, accelerating growth, and creating the preconditions for a robust middle class in the postwar years. It was a double win, and it’s one the Biden administration would like to repeat.

So those are the first two main points to understand about the new industrial policy:

It’s intended to strengthen the U.S.’ hand against China, and

It’s an attempt to at least partially reverse the rise in inequality that happened in the 80s, 90s, and 00s.

Already, there are worries that tensions might emerge between these two objectives — and the objective of stopping climate change. Ezra Klein and other writers (including Yours Truly) have worried about the use of what Ezra calls “everything-bagel liberalism” — the tendency to use any industrial policy as a vehicle for pork for favored Democratic interest groups, while also refusing to alter any piece of government regulation that might stand in the way of building stuff. But the Biden administration and their economic advisors really believe they can have it all. Heather Boushey, an influential member of the Council of Economic Advisors, responded to Klein’s piece in a wry manner:

Meanwhile, Todd Tucker, Director of Industrial Policy and Trade at the influential Roosevelt Institute (and also Boushey’s husband) asserted that “everything-bagel” policy can work, and cited a piece in The American Prospect that argued that job creation is one of the essential functions of the new industrial policy.

Time will tell whether the concerns over clashing objectives are appropriate. If so, the policy agenda will need to deal with that and make hard choices. If not, the U.S. could enjoy another double victory, the way we did in WW2.

Anyway, the next thing to note about the new industrial policy is that it’s not just about trade. Trade policy is just about what kinds of things Americans make for people in other countries, and vice versa; industrial policy is also about what kinds of things Americans make for each other. Those two things are always deeply entwined — a country’s international specialization will have big effects on what their workers make for the domestic market as well — but the Biden administration is going to try to intervene directly in both arenas at once.

The end of the free-trade consensus is also the end of the laissez-faire consensus — the idea that simply having the government stand back and let private companies do whatever they wanted was the optimal strategy for creating broadly shared prosperity. Laissez-faire — which some people call “neoliberalism”, “free markets”, “liberalism”, or “libertarianism” — was never anywhere near as much of a consensus as free trade was, but the pendulum is clearly shifting toward a more interventionist mindset.

And there’s an important lesson here for those who want to alter the direction of policy in America — a “theory of change”, if you will. Although inequality was a glaring problem for a long time, and although climate change was always a looming threat, it took a national security threat for the government to get serious about direct intervention in the industrial structure of the U.S. economy. In a way, national security is the ultimate pure public good — the clearest case for government stepping in and redirecting economic activity.

A fourth key aspect of the new industrial policy is that it’s concrete. Seven years ago, Brad DeLong and Stephen A. Cohen wrote a very short, readable book called Concrete Economics, which had a very clear thesis: The government always has an industrial policy, whether it thinks it does or not. If the government doesn’t aim the economy at specific objectives, but instead allows financial markets to decide everything, the result is actually just an industrial policy that favors the finance industry — with predictably disastrous consequences. Concrete Economics has rightfully become the pocket bible of the new industrialists, and Sullivan clearly echoed its ideas in his speech:

Another embedded assumption was that the type of growth did not matter. All growth was good growth. So, various reforms combined and came together to privilege some sectors of the economy, like finance, while other essential sectors, like semiconductors and infrastructure, atrophied. Our industrial capacity—which is crucial to any country’s ability to continue to innovate—took a real hit…The shocks of a global financial crisis and a global pandemic laid bare the limits of these prevailing assumptions.

DeLong and Cohen argue that a successful industrial policy needs to tell the American people what they’re going to get, in concrete terms. And the Biden administration’s new industrial policy does this. It tells American consumers and workers that they’re going to get cheap electricity, a nice new electric car, a better job, safety from climate change, and safety from domination by the Chinese Communist Party. And it tells American businesses that they’re going to get cheaper energy, cheaper computer chips, and government assistance if they produce things in those sectors.

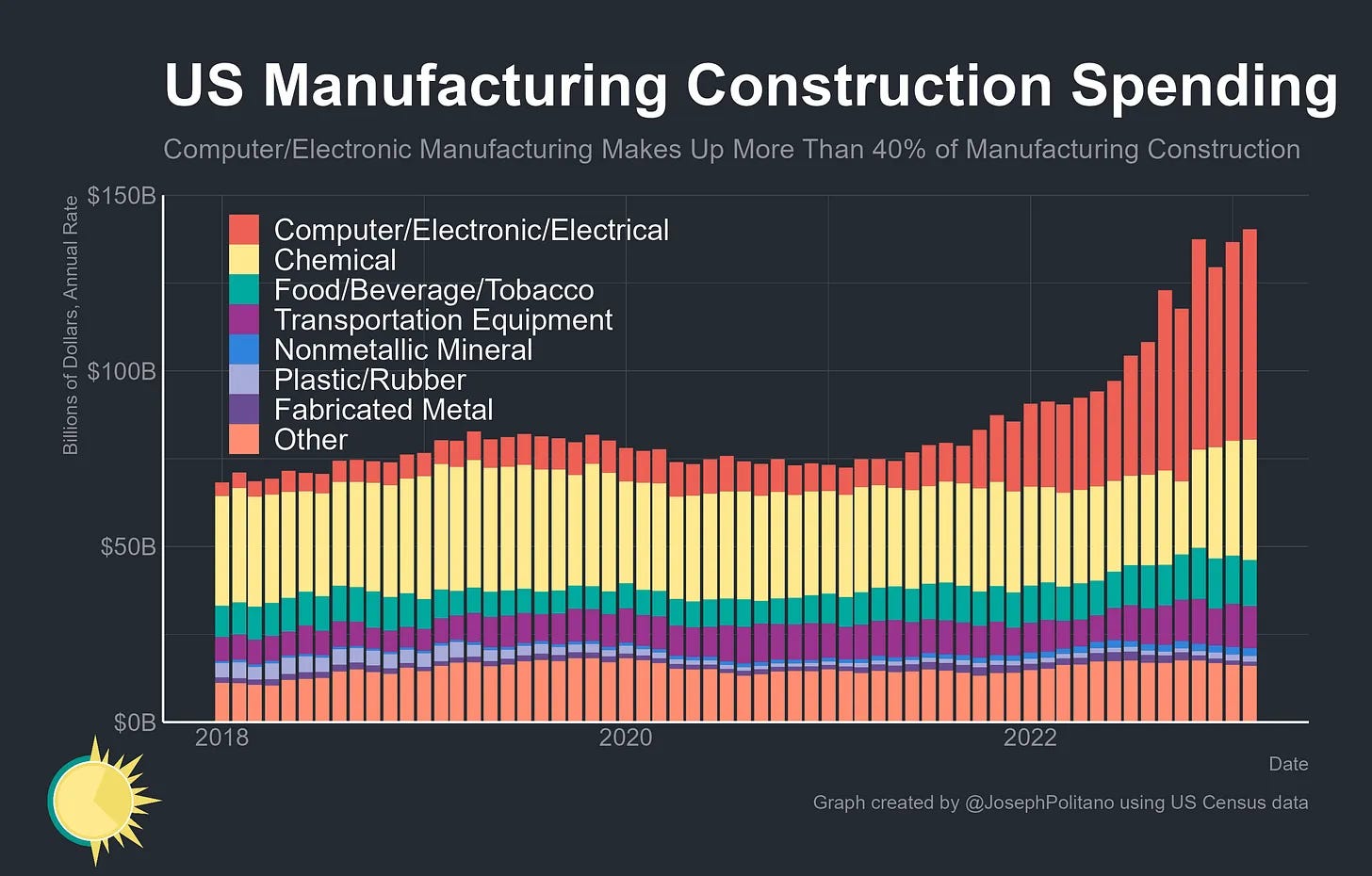

Anyway, there are signs that the vision is working. Though U.S. factory construction in general remains stagnant, new construction in the electronics sector is absolutely booming:

Government spending on climate change is also rising by billions a year.

Of course, it remains to be seen how much of this increased spending will be eaten up by excessive U.S. infrastructure costs, NEPA delays, Buy American provisions, and other toppings on the “everything bagel”, and how much production capacity in chips and green energy we’ll actually get. But the simple fact that money is being spent on actual, physical production capacity at the government’s behest is an encouraging sign.

And I think there’s one more crucial point to understand about the new industrial policy consensus: It’s going to be bipartisan, even though the parties will disagree on many of the details.

To survive the inevitable power transitions in America, a policy paradigm must be bipartisan; at some point, and in fact at many points, Republicans will gain control of Congress and/or the Presidency. If Republicans don’t support at least some of the core features of the new industrial policy, they’ll just repeal and replace it as soon as they win an election.

Fortunately, there are a number of signs that Republicans and Democrats are going to disagree about the implementation of the new industrial policy, but not its basic contours. First, there’s the fact that Trump himself designed some of the pieces of the new policy regime, and was the first President to break publicly with the old free-trade consensus. There’s also the fact that while the IRA was voted in along party lines, the CHIPS Act and an infrastructure bill were bipartisan, and the GOP also included some climate spending in a Covid relief bill back in December 2020.

And beyond these political facts, there’s clearly a bipartisan consensus that China is a big threat and needs to be countered. As in Cold War 1, superpower rivalry looks like the great unifier of American politics. But there’s also a surprising glimmer of bipartisan belief in the inadequacy of free-market economics. Democrats frame this in terms of reducing inequality, while Republicans frame it in terms of boosting the (GOP-supporting) working class. I don’t think either party is fully sincere about this — Democrats have to cater to their high-earning supporters, while Republicans still despise labor and reflexively recoil at any attempt to help the poor. But in general both parties seem to like the idea of creating good jobs for the working class, especially if this happens via the reshoring of industry. It’s only on climate change where there’s little room for agreement between the two parties, which is why no Republicans voted for the IRA.

What Democrats and Republicans will fight over is the implementation of the new industrial policy. Already we can see the battle lines being drawn. If you read publications and speeches from the Roosevelt Institute, they’re all about using industrial policy to help labor, weaken the dominance of powerful corporations, and reverse economic inequities. Meanwhile, conservative thinkers, some of whom appeared at a recent event by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, are going to fight for a version of industrial policy that’s more favorable to business, more deregulatory, more inclusive of fossil fuel industries, and which doesn’t involve giveaways to Democratic interest groups.

These fights over the nature of industrial policy will be fierce, and sometimes even bitter. But we shouldn’t let them obscure the larger point, which is that both parties now agree on the need for industrial policy, and on many of its broad contours. It appears that America has found its new economic policy consensus. What remains to be seen are the results — how effectively the new policy regime can be implemented, and how well it achieves its goals. It’ll also be interesting to see how the economics profession contributes to the effort (a topic for another post).

But in any case, industrial policy is back, and it looks like it’s here to stay for a while.

Update: Eric Levitz also has a good post about this shift, which also includes some useful thoughts on why U.S. industrial policy doesn’t threaten Europe.

The traditional success stories for industrial policy are catch-up stories: the American colonies learning to make what they'd once bought from Britain, Japan and the Asian Tigers going from poor to rich.

Can industrial policy make a real difference in countries that are already rich and have high labor costs?

I guess we'll find out!

Do we really have to give up on free trade though?

My hope has been that we better articulate the distinction between "strategically important" things like semiconductors and "random crap" like sneakers and fidget-spinners...

I have a son who is a bit of a Bernie-type socialist, and he gets caught up on the healthcare issue a lot to say markets don't work. My counter is always that *most things* aren't like that - free market capitalism is doing just fine for getting you Doritos and donuts and most "normal" things you purchase. I feel the same argument applies to free trade.