The Middle East is getting older

Why I'm optimistic about the waning of conflict in the region.

I noticed something interesting about the Israel-Gaza war that seems to have generally been overlooked: The war hasn’t shown much sign of spreading throughout the Middle East. Yemen’s Houthis (one of Iran’s proxy militias) launched a few missiles in the general direction of Israel and bellowed a declaration of war, but no one seems very concerned. Hezbollah, the Lebanese militia that fought Israel to a standstill in 2006, has chosen to stay out of the conflict, as has Iran itself. The “Arab street” that everyone feared back in the early 2000s has certainly had protests in support of the Palestinians, but they’ve been very peaceful. Saudi Arabia has said that it still wants to normalize relations with Israel, conditional on a ceasefire.

This is a very good sign, and it’s far from the dire expectations that everyone was throwing around in the first few days of the war. In 2011, the Arab Spring spread like wildfire, igniting huge, lengthy, bloody wars in Syria and Yemen, as well as various smaller wars throughout the Middle East; the Israel-Gaza war shows no sign of repeating this history.

There could be lots of reasons for this, of course. The region may simply be exhausted after two decades of wars. U.S. deterrence may be restraining Iran’s hand and the hand of its proxies. The Israel-Palestine conflict may simply not be as important to the region as the longer-term cold war between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Etc.

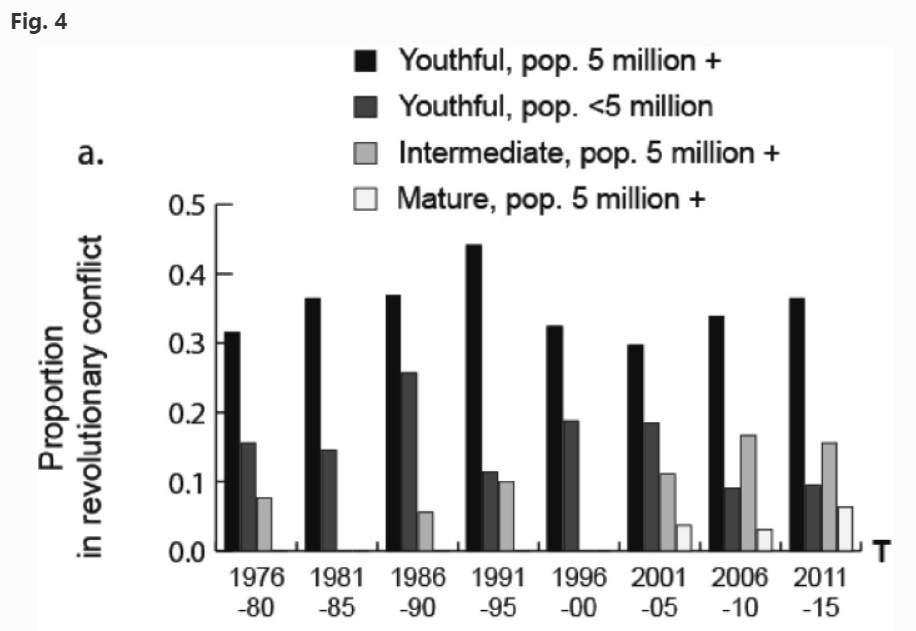

But I think it’s also possible that population aging has something to do with it. There’s a pretty well-established literature linking youthful population bulges to elevated risk of conflict. Of course, that link is just a correlation — it’s obviously hard to find natural experiments that change a country’s age structure, other than war itself. But it’s a fairly well-established correlation. For example, Cincotta and Weber (2021) find that countries with a median age of 25 or less are much more likely to have revolutions:

Urdal (2006) finds:

It has frequently been suggested that…the so-called “youth bulges,” make countries more susceptible to political violence…This claim is empirically tested in a time-series cross-national statistical model for internal armed conflict for the period 1950–2000, and for event data for terrorism and rioting for the years 1984–1995. The expectation that youth bulges should increase the risk of political violence receives robust support for all three forms of violence.

Madsen (2021) writes:

Evidence from the 1990s reveals that countries where people aged fifteen to twenty-nine made up more than 40 percent of the adult population were twice as likely to suffer civil conflict. Between 1970 and 2007, 80 percent of all outbreaks of civil conflict occurred in countries in which at least 60 percent of the population was younger than thirty…Only a few of these countries are rated as democracies, and restrictions on political freedoms, corruption, and weak institutional capacity are also common. Data collected from 1950 to 2000 found that countries where 35 percent or more of their adult populations comprised people aged fifteen to twenty-four were 150 percent more likely to experience an outbreak of civil conflict. The correlation is strongest in the case of countries with consistently high fertility rates. Once the demographic transition is fully under way, outbreaks of conflict are less likely, even though populations remain youthful due to demographic momentum from past high levels of fertility.

Ibrahim (2019) and others find similar results. As always, there are critics of the theory, and some authors make distinctions based on different types of conflicts — for example, Yair and Midownik (2014) claim that youth bulges are less relevant for “ethnic wars”, while Cincotta and Weber (2021) caution that their results are harder to test for “separatist” wars. But be that as it may, the general consensus in the field seems to be that a very young population is correlated with instability and violence.

There are various theories as to why youth bulges might cause conflict. Resource scarcity is an obvious factor in very poor countries. In other countries, there’s a theory that a youth bulge leads to fewer economic and social opportunities for young people — basically, the young people crowd each other out, and this makes them mad. This effect is obviously exacerbated when the economy is stagnating. Also, simply having a lot of young men around without much to lose seems like a risk factor in and of itself.

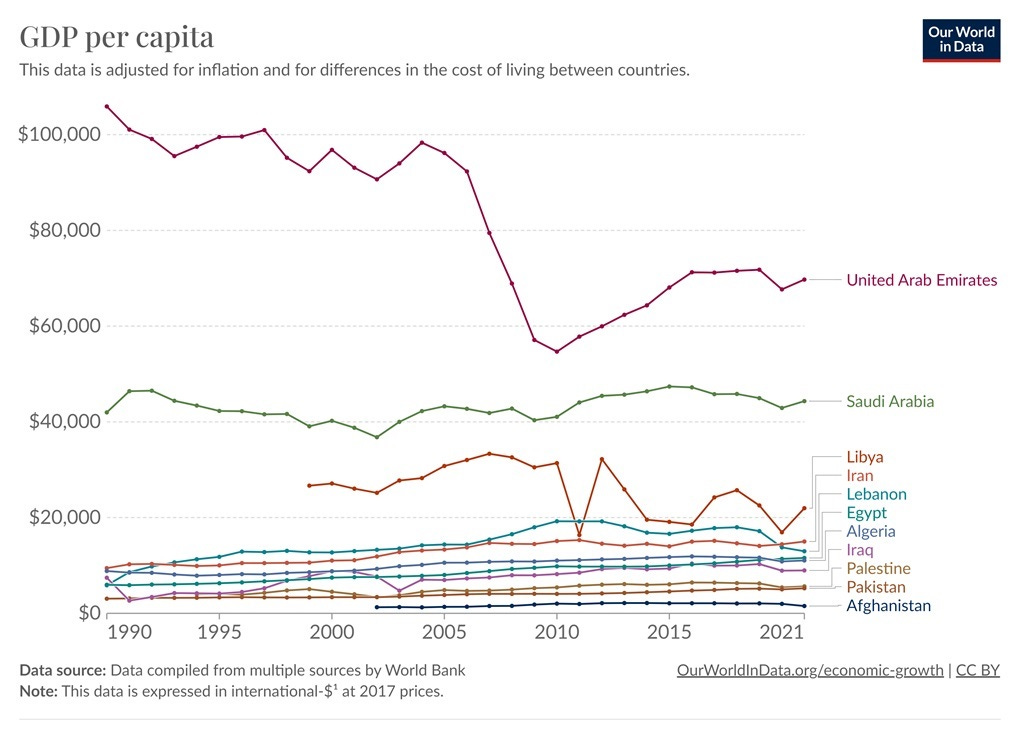

The Middle East’s stagnant economies are obviously a factor in the violence that has ripped across the region (though of course there’s clearly two-way causation there). Whether rich or poor, the countries in the Greater Middle East — I’ll throw Afghanistan and Pakistan into the mix, since they’ve also been a big locus of conflict — just don’t tend to experience much economic growth at all.

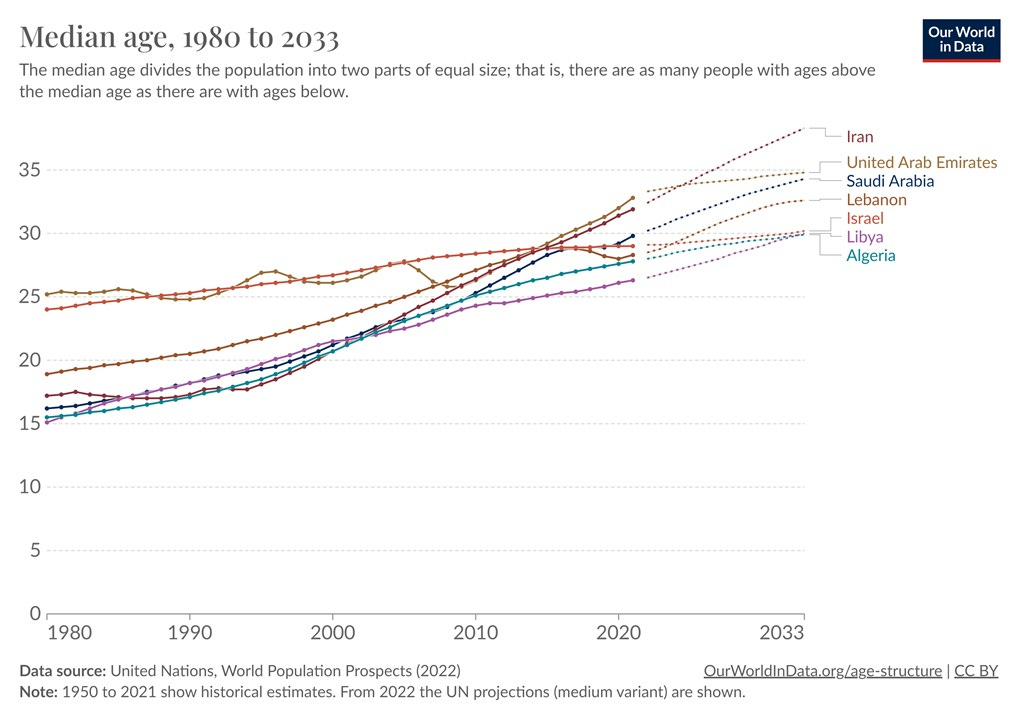

But the good news here, at least from a conflict-avoidance perspective, is that these countries are getting steadily older. There are a number of countries in the region where median age has already passed the 25-year mark:

It’s pretty startling to look at this chart and realize how much things have changed. When Iran threw hundreds of thousands of soldiers against Iraq in “human wave” attacks in the 1980s, the median Iranian was just 17 years old; now, the median Iranian is in their early 30s. That may be one reason Iran has moved away from direct belligerence and toward the use of proxy militias like the Houthis, Hezbollah, and Hamas. Saudi Arabia got involved in the Yemen war, but was reluctant to send ground troops against the Houthis — possibly because the Houthis are formidable, but possibly because the Saudis have relatively few young people to send.

Similarly, the horrible civil wars in Algeria in the 90s and Lebanon in the 80s happened when those countries were far younger than they are today. Hezbollah resides in a considerably older country than in 2006 when they attacked Israel, which may have something to do with why they’re sitting this one out. Of all the countries on this list, only Libya had a relatively recent war.

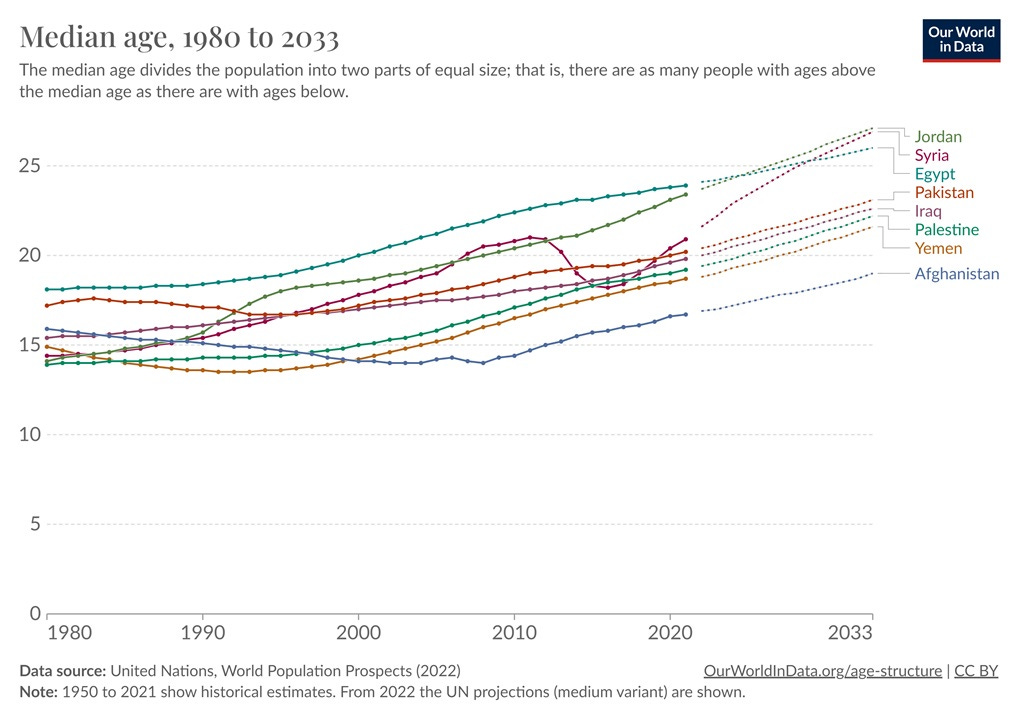

On the other hand, there are a number of other countries in the region that are still pretty young:

I think it’s no surprise that most of the Middle Eastern countries that have had wars in the last decade are on this list. They also include almost all of the countries where Iran has proxies (except Lebanon). And troublingly, Afghanistan, Yemen, Palestine, Iraq, and Pakistan are projected to still be below a median age of 25 a decade from now.

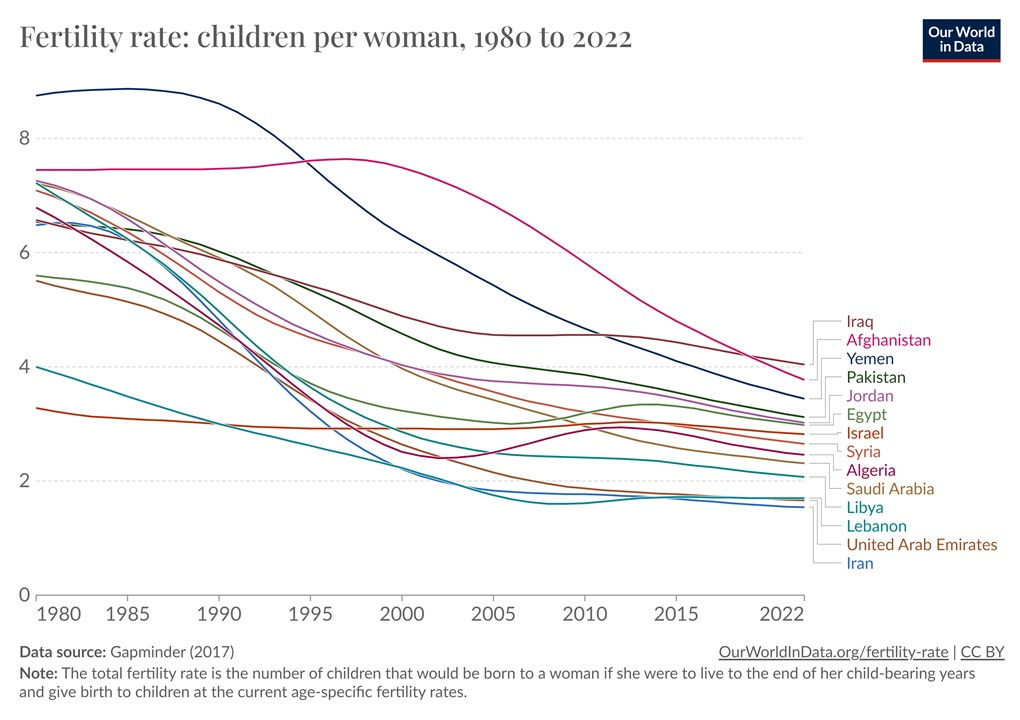

But that said, all of these countries are still aging at a steady clip — as are the countries that are already over 25. The fundamental reason is the big collapse in fertility rates in the Greater Middle East (and across the broader Muslim world) over the past few decades.

(This data source doesn’t have Palestine, but the UN shows it at 3.5 and falling.)

Again, it’s pretty startling to consider some of these numbers. When Iran exploded in revolution and fought a titanic war against Iraq in the late 70s and 80s, its fertility was over 6; now it’s down to about 1.5. When the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001, its fertility was over 7; now, it’s below 4. (By the way, look at that stat and ask yourself if the U.S. occupation might have accomplished more than you thought.)

Falling fertility seems to take the edge off of a youth bulge, even when a country is still pretty young. Urdal (2006) writes:

Youth bulges in the context of continued high fertility and high dependency make countries increasingly likely to experience armed conflict…while countries that are well underway in their demographic transitions are likely to experience a ‘‘peace dividend.’’

Anyway, I don’t want to claim that “demography is destiny” here, and it’s all too easy to look at individual countries and tell just-so stories about how aging and fertility might have affected their conflicts. And even if an older population and fewer children do make war less likely, there are still a handful of war-torn countries — Afghanistan, Yemen, Iraq, Palestine, and Syria — that are still young and still have fairly robust fertility.

But it’s hard not to look at these graphs and feel that something big is changing. The old Middle East, with massive crowds of angry young people thronging the streets, ready to explode into nationalist or sectarian or revolutionary violence, is steadily disappearing, being replaced by a more sedate, aging society. Given the horrific outcomes of the last few decades, it’s hard not to see that as a good thing.

What if it's not the populations getting older, but the borders? If you look at a map, you can see a strange pattern: young borders are violent borders.

Israel is one of a handful of countries partitioned and made independent only after World War 2. Who else is on that list? South Korea, Ukraine, Kosovo, Pakistan, Eritrea, Taiwan -- all countries with a neighbor on the regular edge of war.

Excluding pure no-border-change decolonizations, it seems every single post-1945 state formation has come with at least one "hot" border that regularly flares close to war.

Maybe half of Israel's tensions are simply that neither its citizens or its neighbors have come to take its existence for granted. And maybe that isn't about religion or race or policies, but just the passage of time.

This doesn't excuse Israel or Hamas or the Arab states when they do awful things. But it might mean it's not mysterious why they do those awful things: they still have the embers of a "revolutionary mindset", where the state's rights and extent must continually be asserted in the most idealistic extremes possible. Yet those revolutionary mindsets do decay: everywhere in the world with older borders, war is much rarer. Filter out the world's young borders, and you'd filter out 90% of the interstate war.

If you think Israel is special for having neighbors who regularly threaten to violently wipe it from the map, think about South Korea, or Taiwan. You don't need a special policy or a special religion to have a violent border. To get violence and danger, all you need is to have borders that are young.

Alright I'm a conflict geographer and this is an accurate take. However, Ukraine and Russia have the worst birthrates and demographics and they still went to war because this is Russia's last chance to defend itself before it doesn't have an army of young men to fight with. The real question is the conflict brewing in the Sahel and the ensuing refugee Crisis that will overwhelm Europe soon. Happy to do some geospatial modeling with you on this topic!