The death (again) of the internet as we know it

A few big changes are making the online world a more boring place to hang out.

The internet as we know it has already died once. In the 2010s, the rise of smartphones and mass social media (Twitter/Facebook/Instagram) caused what internet veterans refer to as an Eternal September event, for the entire internet. “Eternal September” is an old slang term for when a bunch of normal folks flood into a previously cozy, boutique online space. When the average person got a high-speed pocket computer that linked them 24/7 to the world of social media, the internet ceased to be the domain of weirdos and hobbyists, and became the town square for our entire society.

That wasn’t a great change, in my opinion. The human race didn’t evolve to all be in the same room together. The early internet was a very special time, when the online world served primarily as a temporary escape or a release valve for anyone who didn’t quite fit in in the offline world; mass social media turned the internet into a collective trap, a place where you had to be instead of a place where you could run away to. If you look at charts of teenagers’ well-being in the U.S., you can see that things got better from the mid-90s through the 2000s, and then got dramatically worse:

But the age of mass social media was probably a necessary intermediate step to a better digital world — we learned that communities need moderation and the opportunity for exit. I wrote about that evolution in a post back in 2022:

You can sort of see this evolution in usage statistics. Twitter and Instagram usage are trending down:

Anecdotally, when I meet people in their early to mid 20s, they don’t want to connect over Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook Messenger, like young people did in the 2010s. They just exchange phone numbers, like people did in the 2000s. Everyone is still online all the time, but “online” increasingly means group chats, Discord, and other small-group interactions. As a society, we are re-learning how to center our social lives around a network of people we know in real life, rather than around a performative feed in which we broadcast our actions and thoughts to a bunch of strangers.

Good.

But I suspect there are some additional trends driving young people off of the public internet and into more private spaces. In just the last few years, a number of forces have transformed both social media and the traditional Web. Some of these are making the experience of the public internet more boring, while others are turning it into something more akin to television. Here are a few of the trends I see:

Ads ate the free internet (“enshittification”)

The term “enshittification” was coined by Cory Doctorow, one of my favorite sci-fi authors, and a keen observer of internet trends. In a Medium post in 2022 and an article in Wired in 2023, he argued that a social media platform has a predictable life-cycle:

First it lures a bunch of users with a great (and free) user experience, to create a network effect that makes it hard for people to leave.

Then, in order to make money, it attracts a bunch of business customers by doing things like selling user data and spamming users with ads. This makes the user experience worse, but the users are trapped on the platform by a network effect.

Finally, the platform tries to extract more value from its business customers by jacking up fees, offering its own competing products, etc. This makes the platform a worse value proposition for the business customers, but because all the users are still on the platform, and because of their own sunk costs, the advertisers can’t leave. This is what Tim O’Reilly calls “eating the ecosystem”.

This is a very plausible model of how social media platforms work. And since platform network effects draw users away from traditional websites, it’s increasingly a description of how the entire public internet works.

But for most regular folks, the only step that matters here is Step 2 — the relentless proliferation of ads and other ways that previous user-friendly social-media platforms monetize their eyeballs.

Google is a great example. For many years, Google was the front page of the internet — a plain, simple text bar where you could type what you were looking for and immediately find websites offering you information about what you wanted. In recent years, though, Google has relentlessly monetized its ad search monopoly by increasing the amount of advertising on the platform. For example, if I want to learn about drones on the Web, there was a time when I could just search for “drones”. Now, the first and second pages of results are all ads trying to get me to buy a drone:

And when I get to the actual search results on the third screen down, it’s all just e-commerce sites offering to sell me more drones. I don’t even get to the Wikipedia link until the fifth screen down!

In other words, using Google is now akin to a video game, where the challenge is to craft a search query that avoids ad spam and gets you to the well-hidden information that you actually want. That’s not the most fun video game in the world, so when I can I now use ChatGPT (which is not yet enshittified). But ChatGPT doesn’t work for a lot of things, and so I’m stuck playing this awful, boring video game of “dodge the ads”.

What’s more, platforms that depend on Google for their traffic are often very good at SEO these days, and their sites are often enshittified as well. For example, if you type a question into Google, you’ll often get a bunch of links to Quora. A few years back, Quora was a great place to find quick and in-depth answers to a lot of questions. As of 2024, however, it is…not. Back in February, I screenshotted a Quora results page, and annotated it with my reactions:

For what it’s worth, Reddit is still pretty useful for getting answers quickly and effectively, but I’m sure at some point they’ll figure out how to change that in order to make more money.

I don’t use Facebook much anymore, and Instagram barely at all (and I don’t even have TikTok installed). So I haven’t seen the process of enshittification at work on those platforms, but the stories all indicate it’s substantial.

In fact, all this is to be expected — companies want to make money, and a network effect is a powerful engine of profit. To some degree, the sky-high stock prices of these companies probably always embedded the implicit assumption that they would be enshittified at some point. But nobody knows how severe the enshittification has to get, and for how long, before it overcomes the network effect and people actually just start walking away from platforms — and even from the Web itself. The chart above suggests that this may already be happening.

Algorithmic feeds: back to push media

“Push media” is a term from marketing. It refers to media like TV and radio, where the user’s only interaction with the content is to decide what to watch. The content is thus “pushed” to the user.

When the Web and social media came along, users suddenly got the chance to interact with content a lot more. They could like, upvote, downvote, etc. They could talk directly back to the creators, in full public view, via tweet interactions, Facebook page comments, and so on. But most importantly, users could curate their feeds. With TV or radio, you could switch channels, but with social media feeds, you could assemble a list of content providers that defined your media diet in extreme detail.

You can still do that on some platforms, with what’s now called a “chronological” feed. But platforms have generally switched to — or at least, heavily encouraged users to switch to — algorithmic feeds, in which what you see is determined by an AI. Your views and likes and other interactions still provide feedback to that algorithm, but the feedback is highly imperfect. Excellent Twitter accounts that I used to see all the time now appear only rarely in my algorithmic feed, because they’re the type of content that I tend to read but not to retweet. Keeping them in the algorithmic feed requires constant conscious effort on my part; usually it’s not worth it.

This is a big shift back toward push media. With an algorithmic feed, much of what you see is mediated by the company that owns the platform — it pushes different things to different people based on what its computer thinks they’ll like, but it’s still pushing.

In some ways, algorithmic feeds are even pushier than TV or radio were! With TV and radio you could change channels, and the device would dutifully deliver you the channel you picked. With algorithmic social media, there’s really only one channel, even though it’s personalized — Twitter is just a single feed, TikTok is just a single feed, etc. Sure, you can go to a specific creator’s “channel”, but most content isn’t consumed this way. With TV and radio, a few creators generate huge amounts of content, but social media is more about a large number of creators generating small bits of content. So social media is typically consumed via feeds, and you have only one feed per platform.

I’m not claiming that algorithmic feeds are bad. They’ve helped me discover lots of interesting stuff that I wouldn’t have seen otherwise. But they represent a major qualitative change in what the internet is. For decades, despite all of the changes in platforms — Usenet and IRC to the Web to social media — the internet was still a place where you sought out information and communication with others instead of having content delivered to you. Now, with algorithmic feeds, there’s another layer between you and other people on the internet — a computer that at least partially decides who you hear from and who you talk to.

This means that over time, the internet becomes a more passive experience. The incentive is to keep scrolling, instead of talking to other people. And although Substack is thankfully still subscription-based, if I were trying to make a living by creating content for YouTube or TikTok or Instagram, I’d probably be trying to optimize for whatever I thought the algorithm would pick up. That’s not necessarily bad, but it’s not what the internet used to be.

Update: Here is a good and thoughtful post by Byrne Hobart on this shift.

China and Russia: the Big Boys came out to play

Another big change in the internet is the relentless rise of state actors in the U.S. information ecosystem. Russian disinformation efforts are very old news by now — the Russian government tries not just to influence American opinion on Ukraine aid, but also to generally sow social division in American society. For example, the Russians try to foment panic about immigration:

For Vladimir Putin, victory in Ukraine may run through Texas’ Rio Grande Valley.

In recent weeks, Russian state media and online accounts tied to the Kremlin have spread and amplified misleading and incendiary content about U.S. immigration and border security. The campaign seems crafted to stoke outrage and polarization before the 2024 election for the White House, and experts who study Russian disinformation say Americans can expect more to come as Putin looks to weaken support for Ukraine and cut off a vital supply of aid.

In social media posts, online videos and stories on websites, these accounts misstate the impact of immigration, highlight stories about crimes committed by immigrants, and warn of dire consequences if the U.S. doesn’t crack down at its border with Mexico. Many are misleading, filled with cherry-picked data or debunked rumors.

This is a very old Russian strategy for competition with the U.S.; the Soviets tried to exacerbate racial divisions in America in the 1960s. But social media has supercharged these efforts, because it’s disintermediated. In the 1960s, CBS and the New York Times wouldn’t run Soviet propaganda, meaning the Soviets had to work hard to get their message to American kids through alternative media channels and human networks. In the modern day all they have to do is to sign up for a bunch of Twitter accounts and go directly into people’s replies. Bots have added another force multiplier.

Russian operations have changed Twitter, by flooding the site with accounts like this one:

This has changed my own experience of Twitter on a day-to-day basis — they frequently reply to my tweets, and I see them in the algorithm. More ominously, any discussion on the platform is now liable to get spammed by racist and antisemitic content — some of it driven by bored teenagers, no doubt, but some of it driven by Russian accounts always probing for cracks in the American social fabric.

China is now in on the influence operations game as well. Although it’s much less skillful than Russia at sowing disinformation directly, it has an incredibly powerful weapon in its control of the TikTok algorithm. As social media becomes less and less disintermediated thanks to the rise of algorithmic feeds, being able to tweak those algorithms secretly in order to suppress or amplify certain content becomes an information-warfare superpower.

There is now pretty incontrovertible evidence that China actively manipulates TikTok’s algorithm in order to suppress topics it doesn’t like. Here’s a graph showing relative frequency of hashtags on Instagram and Tiktok — for most political topics TikTok runs at about 40% of Instagram, but for China-sensitive topics it’s more like 1-5%:

This is mostly just silent censorship of Americans’ viewpoints. American TikTok users don’t even realize it’s happening, so it’s unlikely to make their experience of the internet substantially more negative. But over time, TikTok’s promotion of divisive attitudes in the U.S. could potentially infect human opinion, making the internet even more extreme and shouty than it already was.

Of course, there were always actors trying to spam social media with disinformation, influence operations, and so on — corporations, political parties, interest groups, and so on. But the governments of China and Russia are just much better-resourced than any of those other actors — they have a lot more money, a lot more people, and a lot more technology devoted to the effort. The Big Boys have come out to play, and they have changed our internet, generally for the worse.

Slop

The factors I’ve mentioned thus far were in place even before ChatGPT and Midjourney and other generative AI applications exploded in capabilities and came into widespread use. Now, the marginal cost of producing reasonably high-quality images and text has gone to near zero. And so people are using generative AI to fill up social media with…stuff.

The blog Garbage Day, one of my favorite blogs for keeping track of internet memes (the other being Infinite Scroll), has a good post about this…stuff. Here’s a picture of some images from Facebook, featuring kids driving cars made of plastic bottles:

And Max Meyer has been going down the rabbit hole of social media cooking videos displaying nonsense recipes made by AIs, with AI narration. And it only gets weirder from there.

What is the point of images of kids driving cars made of plastic bottles? What is the point of nonsense recipes? The answer is: There doesn’t have to be a point. Since the marginal cost of producing this stuff is essentially zero, and there’s at least some nonzero chance that any one of these random things will catch on and become a meme and get people to subscribe to a channel and make some ad dollars, it makes sense to spam as much of this slop into the world as you can.

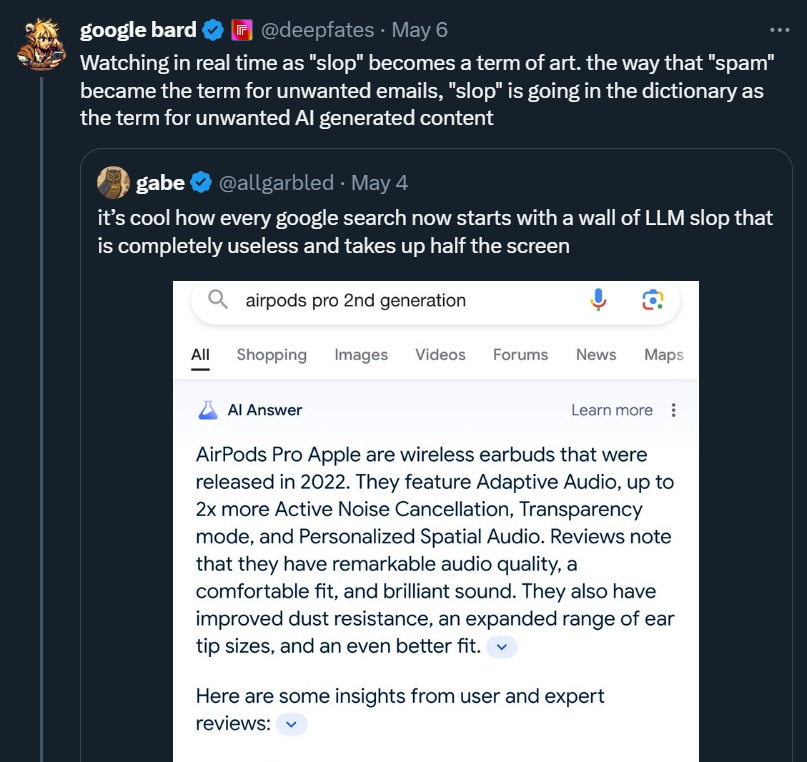

“Slop”, in fact, is quickly becoming the standard term for mediocre-to-bad AI-generated content:

From the standpoint of any single generator of slop, it can be an economically rational proposition to generate more and more of it. But it produces a negative externality, which is that everyone else’s experience of the internet becomes increasingly filled with boring, mildly annoying slop. And in the future, the problem might get even worse; AIs might even train themselves on AI-generated slop, turning the entire internet into a recursive ouroboros of slop. The “Dead Internet Theory” is currently a silly fun conspiracy theory, but it might come true in the not-too-distant future.

Into the Net of Lies cometh the God of Lies

The late Vernor Vinge, one of my favorite science fiction authors of all times, wrote a series in which the galactic internet was dubbed the Net of a Million Lies (obviously making fun of his own experiences on Usenet). This is related to the common saying that “A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on” — since the marginal cost of producing misinformation is much smaller than the marginal cost of refuting misinformation, a free and disintermediated marketplace of ideas will tend to spread a lot of lies. There’s plenty of research showing that misinformation actually spreads faster on social media than true information.

This is why humanity has traditionally relied on informational gatekeepers — newspaper editors, TV anchors, and so on — to prevent us having to become full-time fact-checkers. Social media has very few such gatekeepers, and there was a huge (and ongoing) debate after the 2016 election about whether we need some sort of corporate editorial control in order to cut down on the amount of misinformation spreading on social media.

I won’t recap that debate here, but I will say that generative AI absolutely supercharges the problem. Deepfakes of someone’s voice are now almost trivially easy to produce, AI-doctored images are easy, and deepfake videos are getting there. This isn’t a speculative problem for the future — it’s happening right now.

AI fakery can be used for scams:

A finance worker at a multinational firm was tricked into paying out $25 million to fraudsters using deepfake technology to pose as the company’s chief financial officer in a video conference call, according to Hong Kong police.

The elaborate scam saw the worker duped into attending a video call with what he thought were several other members of staff, but all of whom were in fact deepfake recreations, Hong Kong police said at a briefing on Friday.

AI fakery can be used for personal revenge:

Baltimore County Police arrested Pikesville High School’s former athletic director Thursday morning and charged him with crimes related to the alleged use of artificial intelligence to impersonate Principal Eric Eiswert, leading the public to believe Eiswert made racist and antisemitic comments behind closed doors…Darien was charged with disrupting school activities after investigators determined he faked Eiswert’s voice and circulated the audio on social media in January[.]

AI fakery can be used for politics:

Days before a pivotal election in Slovakia to determine who would lead the country, a damning audio recording spread online in which one of the top candidates seemingly boasted about how he’d rigged the election…The recordings immediately went viral on social media, and the candidate, who is pro-NATO and aligned with Western interests, was defeated in September by an opponent who supported closer ties to Moscow and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

While the number of votes swayed by the leaked audio remains uncertain, two things are now abundantly clear: The recordings were fake, created using artificial intelligence; and US officials see the episode in Europe as a frightening harbinger of the sort of interference the United States will likely experience during the 2024 presidential election.

AI fakery can even be used for corporate media content:

Netflix has been accused of using AI-manipulated images in a new true crime documentary What Jennifer Did…The documentary revolves around Jennifer Pan who was convicted of a kill-for-hire attack on her parents. Around 28 minutes into the documentary, Pan’s high school friend Nam Nguyen is described as a “bubbly, happy, confident, and very genuine” person. His words are accompanied by a series of relevant photos…But upon closer inspection of the images, there are signs of manipulation; one image in particular showing Pan flashing peace signs with both arms appears blatantly manipulated offering evidence that at least some of the image was AI-generated.

It’s not yet clear how deepfakes can be controlled. States are rushing to roll out regulations designed to limit deepfakes, but whether it’ll even remain technologically possible to detect a deepfake as the technology improves is uncertain. One possible future equilibrium is that people just learn not to trust anything they see or hear on the public internet (or on an unverified phone call, text, or email).

Perhaps we’ve finally perfected the Net of Lies by creating a God of Lies to rule over it.

So the internet as we know it — social media sites and the Web — is becoming a generally worse place to hang out. Wading through oceans of advertisements, algorithmic randomness antisemitic Russian bots, Tiktok-poisoned shouters, AI slop, and deepfakes is just not a fun way to spend anyone’s precious limited lifetime.

Better, perhaps, to simply withdraw from the public internet — to spend one’s time chatting directly with friends and in small groups, having fun offline, and maybe watching TV or reading a book or a Substack. That sort of human interaction worked fine before the internet, and it will probably work just fine today. Which is why despite the fact that all of the trends I mentioned are negative, I’m optimistic about the future of our digital communications and our media diet. Maybe someday historians will look back on the era when we lived our lives on social networking sites as a brief anomaly.

My takeaway from Noah's essay is that some Internet companies can only increase revenue by worsening the user experience. It's hard to believe that this will end well for them.

I encountered this paragraph today on ADDISON DEL MASTRO's sub stack.

"The downside of social media is more subtle and corrosive. It’s the mental distress that comes from being made aware of the sheer lunacy with which you share your society. It does something to you—your ability to trust people, your ability to judge words and arguments at face value instead of straining to hear the dog whistle, your general outlook—knowing that people with these views exist. This knowledge never goes away, or breaks down. It accumulates, a mental persistent organic pollutant, and the symptoms of its poisoning are jadedness, guardedness, and distrust."

https://thedeletedscenes.substack.com/p/trolling-alone