The case for high-skilled immigration reform (and how to make it happen)

A guest post by Alec Stapp and Jeremy Neufeld

I’m a fan of all kinds of immigration — I think they all strengthen our country. But I pay special attention to high-skilled immigration, for a number of reasons — because it’s strategically important, because it gives our economy an especially big boost, and because convincing skilled immigrants to come is not always easy.

In the last year or so, the Institute for Progress — a new think tank in D.C. championing policies to speed up technological progress — has been pushing hard to increase skilled immigration. So I asked IFP cofounder Alec Stapp and Senior Immigration Fellow Jeremy Neufeld to write a guest post laying out the case for focusing on skilled immigration, and what specific steps they’re looking at.

Immigration is America’s superpower. According to research by William Kerr at Harvard, between 2000 and 2010, America received more migrating inventors than every other country combined.

However, for decades, our broken immigration system has stacked obstacles in front of immigrants, succeeding in spite of itself thanks to the overwhelming desire of global talent to move here. But this pattern of migration that has served the U.S. so well is starting to change. Facing ever-growing wait times for green cards in the United States, talented immigrants are increasingly looking abroad for opportunities. According to a survey released last year by Boston Consulting Group, for the first time Canada has replaced the U.S. as the most desirable location for migrants moving for work.

Luckily, there are a number of novel executive actions and legislative reforms to boost high-skilled immigration that have recently become politically tractable.

But first, we have to understand the broader context of immigration as a political issue. If we want to make tangible, concrete progress in this critical area, then we should focus on two questions: How do we maximize the benefits from the level of immigration that citizens of a democracy are willing to tolerate? And how do we build public trust over time to increase the rate of immigration in a way that is politically sustainable?

The best answer to both questions is via high-skilled immigration.

How do we maximize the benefits from immigration?

For a given level of immigration, scientists, engineers, inventors, and entrepreneurs deliver the largest benefits.

Despite making up just 14% of the population, immigrants are responsible for 30% of U.S. patents and 38% of U.S. Nobel Prizes in science. A team of Stanford economists recently estimated that nearly three quarters of all U.S. innovation since 1976 can be attributed to high-skilled immigration.

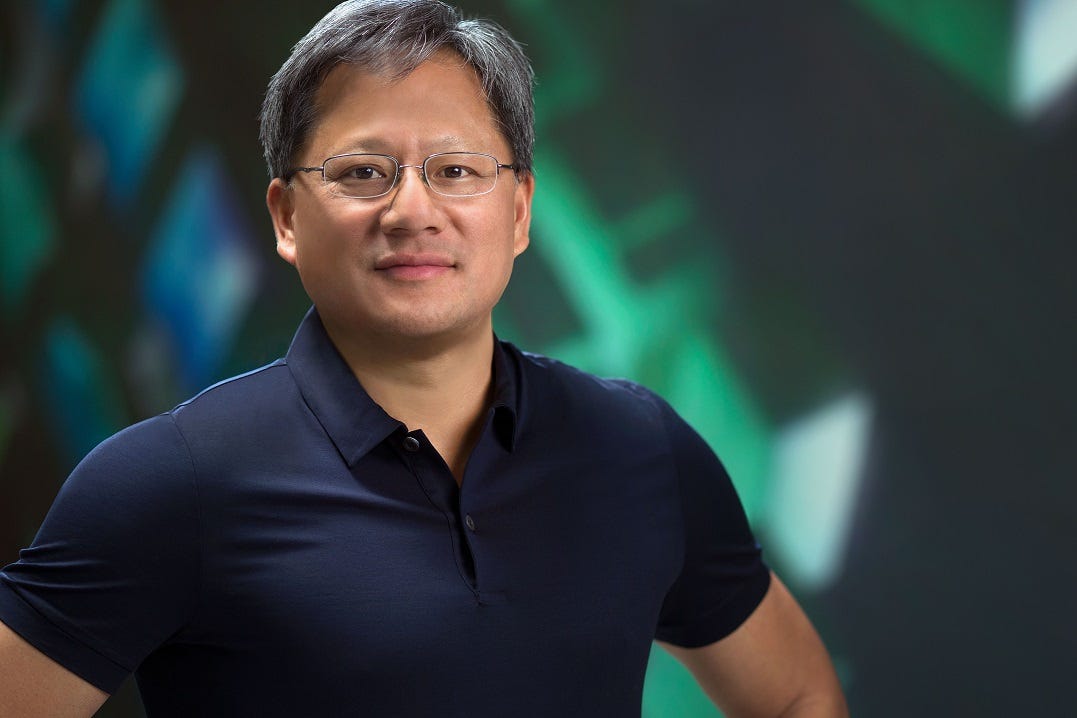

Immigrants’ contributions in the business world are comparably impressive. Recent analysis by the National Foundation for American Policy found that 55% of billion-dollar startups in the U.S. were started by immigrants. Somewhat ironically, the U.S. is actually the home of the most valuable company cofounded by someone born in “South Africa (Tesla), Russia (Alphabet), Ireland (Stripe), Taiwan (Nvidia), Kenya (Cognizant), Lebanon (Moderna), or Bulgaria (Robinhood),” as Byrne Hobart recently pointed out.

Shifting superstar talent to the U.S. benefits not only our country but also the world. Immigrants are more productive in the United States than in other countries because we are at the frontier of science and technology and have unmatched innovation clusters centered around world-class universities and deep capital markets. One recent paper looked at competitors in the International Math Olympiad competition and followed them throughout their careers. This study found that “migrants to the U.S. are up to six times more productive than migrants to other countries — even after accounting for talent during one’s teenage years.” Further, immigrants help bring technologies from the frontier to developing countries.

And immigrants aren’t just economic contributors. Lawmakers in Washington increasingly recognize that skilled immigration can be a powerful lever against a belligerent China. Today, defense-related industries disproportionately turn to international talent to find workers with advanced STEM degrees. And there is nothing new about the idea that attracting the best and brightest can be a major strategic asset — it has been a major benefit to U.S. security from the Civil War through WWII, the Cold War, and beyond.

How do we increase immigration in a politically sustainable way? Other developed countries have figured out how

Increasing the rate of immigration in the short run is counterproductive if it sparks a political backlash that ultimately leads to restrictions on immigration in the long run. In a paper analyzing U.S. election data, Anna Maria Mayda and coauthors show that high-skilled immigration does not carry a political cost (in fact it appears to be a political asset), but low-skilled immigration does. Research by Martin Ruhs shows that greater high-skilled immigration is correlated with a country being more open to immigrants.

Countries like Canada and Australia, though smaller than the U.S. in absolute size, have a much higher foreign born share of their population. They’ve been able to do this, in part, by using some version of a “point system” or other selection mechanisms that tilt immigration toward highly educated or skilled workers. In the U.S., only 36% of immigrants have a college degree, while in Canada and Australia, the shares are 65% and 63% respectively.

We can also look to the U.K. as a case study. Prior to Brexit, E.U. citizens were able to live, work, and study in the U.K. and negative public sentiment toward immigration rose with the annual rate of immigration. But after the Brexit referendum, once the public felt they were in control of their borders, negative sentiment toward immigration plummeted while immigration rates remained high, according to recent analysis by the Financial Times. And after free movement ended post-Brexit, the U.K. government expanded opportunities for high-skilled workers, launching its Global Talent visa and the High Potential Individual visa.

As this example shows, supporting incremental changes to boost high-skilled immigration, while working to secure the border to promote a perception of control, might be the clearest path to strengthening public trust in expansionist immigration policies.

Why comprehensive immigration reform hasn’t succeeded

A majority of Americans (66%) say they would prefer to either increase the rate of immigration or keep it the same, according to Gallup. A minority — 31% — want to decrease it. But here’s the catch: Voters who oppose immigration care about the issue much more deeply than voters who support immigration. And their willingness to vote on this issue in Republican primaries is why many Republican politicians campaign on immigration restriction. Polls also show that voters “trust” Republicans more than Democrats on immigration (37% to 27% in one recent poll), which is why Democrats’ electoral chances suffer when the salience of this issue goes up in the media (e.g., when there’s video on cable news of migrants at the Southern border).

Fortunately, voters are more positive about high-skilled immigration. According to Pew, 78% of voters support high-skilled immigration, including 63% of those who said the country should allow fewer or no immigrants. But if high-skilled immigration reform is so popular, why hasn’t it happened yet? On the Republican side, party leaders say they support legal, skilled immigration, but in practice key members block any legislation that would actually increase the total number of immigrants. Meanwhile, Democrats have pursued a fruitless strategy since the early 2000s of tying all immigration issues together in the hopes of passing comprehensive immigration reform.

Why the time is right for a different approach

After their best chances of comprehensive reform evaporated, Democrats appear to be trying a new strategy. Last year, Senator Menendez, a key Democratic leader on immigration issues, expressed new openness to an incremental approach, saying that “if there are moving vehicles where parts of [immigration reform] can happen, I think all of us would certainly say we want to … attach significant elements to a moving vehicle.” And this approach appears to be picking up steam as lawmakers recognize that importing the world’s top talent is our best tool for staying ahead of our adversaries. The America COMPETES Act, which included a provision for a green card cap exemption for immigrants with advanced STEM degrees, passed the House of Representatives in February with nearly every Democrat voting in favor of the bill.

Republicans seem to be interested too. Senator Todd Young said earlier this year that “in terms of skills-based immigration reform, I think it’s essential to maintaining our national competitiveness.“ His comments have been echoed by other members of his caucus such as Senators Cassidy, Cornyn, Braun, and Lankford. Even Senator Chuck Grassley, a longtime immigration skeptic, has said this is an issue on which he has “changed [his] mind completely.”

With the return of Great Power politics, policymakers understand that high-skilled immigration is how we can beat China and Russia. Less than 0.1% of China’s population is foreign born. On surveys, potential migrants do not say they want to move to China. And since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the tech talent pipeline is flowing out of Russia, not into it. But we’re not currently taking advantage of this potential influx of talent to stay ahead of our rivals. Earlier this year, dozens of former national security leaders, including Cabinet-level officials from both parties, warned Congress that targeted STEM immigration reforms are a national security imperative. Meanwhile, Chinese leaders claim U.S. complacency about high-skilled immigration is a Chinese asset. And as Chinese incomes increase, Chinese talent recruitment programs may prove more attractive than they have been so far.

Unfortunately, the America COMPETES Act stalled after passing the House and the green card cap exemption for immigrants with advanced STEM degrees didn’t make it into the compromise bill — the CHIPS and Science Act — that President Biden signed into law on August 9th. Which is a shame, because the $52 billion in subsidies for US-based semiconductor manufacturing will not be nearly as effective without the necessary talent to actually build and staff the fabs. The founder of TSMC doubts the U.S. can become a world leader in computer chip manufacturing because we lack the talent. So far he’s been proved right: the 5 nm fab in Arizona has already reportedly experienced delays because of labor shortages.

Legislation can fix our high-skilled immigration pipeline now

While Congress could theoretically redesign the high-skilled immigration system from the ground up, this is a pipe dream any time soon. However, modifying existing programs is an easier lift, and has enormous potential to reinvigorate America’s moribund high-skilled pathways.

There’s much for Congress to do, from allowing international students “dual intent” to make it easier for them to stay after graduation, to providing the necessary resources to USCIS to process visas efficiently and bring their system into the digital age.

The most essential action Congress should take is to lift the overly restrictive caps that are holding back green cards from highly qualified and promising talent. Employment-based green card caps are the key bottleneck for high-skilled immigration that only Congress can fix.

This bottleneck imposes major limitations on U.S. potential in two ways. First, it makes the U.S. a less attractive destination for potential immigrants, especially as compared to other countries like Canada and the UK which have taken active steps to attract talent with faster, more flexible options for permanent residency. Second, they force the immigrants who still want to come here through poorly designed and restrictive temporary visa programs that limit their opportunities while they wait for a green card. Many students who lose the H-1B lottery elect for more schooling they don’t really want since they are barred from employment. And many people stay at “safe” companies rather than take risks with startups.

In other words, we’re inflicting a double wound: denying ourselves access to top minds, and even for those who do come into the country, keeping them from pursuing their full potential. Lifting these caps would ensure that immigrants have the freedom and ease to put their talents to the best use.

Fortunately, Congress appears increasingly open to this idea. In addition to the green card cap exemptions for advanced STEM degree holders in the America COMPETES Act, the House version of the Build Back Better Act included provisions that would have lifted the green card caps for people in the United States who have been stuck in the green card queue for at least two years, if they paid a fee. And the White House suggested a version of this idea in the Ukraine supplemental bill that would have exempted certain Russian scientists and engineers from the caps.

While none of these provisions has been passed into law, there’s clearly growing interest on Capitol Hill in targeted cap exemptions. With support from both Republicans and Democrats, these provisions could be a part of bipartisan immigration negotiations in the Senate. And even if those talks fall apart, there will be opportunities to attach the provisions to future spending bills. Lawmakers could use reconciliation (where the door appears to be open for high-skilled cap exemptions unlike other immigration proposals dealing with the undocumented), the annual National Defense Authorization Act (given the increasing realization of the strategic importance of talent for the defense industrial base), or Department of Homeland Security appropriations bills. Especially if paired with sufficiently high fees, high-skilled immigration can be a pay-for that brings in revenue and reduces the price tag of big bills.

The political possibilities could be even wider if Democrats were open to negotiating on certain family sponsorship categories. The F-4 category for adult siblings is already basically unusable because of decades-long backlogs (people getting F-4 visas today have already been waiting for at least 15 years — and often longer — and the likely wait times are far worse for people applying today) and Democrats have shown a willingness to cut the category in previous immigration deals. Democrats may be less willing to make such concessions in an even more polarized political environment, but it would open the potential for more ambitious reforms if the Republicans’ interest in merit-based immigration proves to be more than lip service. So far, Republicans have yet to offer a merit-based reform bill that adopts a point-system without slashing legal immigration levels. But they could substantially shift the debate if they separated their calls for greater selection from proposals to decrease immigration.

Executive action

Beyond the halls of Congress, the executive branch also has significant power to improve high-skilled immigration. In January, the White House announced four initiatives to help the U.S. attract and retain STEM talent from around the world. It was an excellent first step, but large opportunities remain.

The O-1 visa for extraordinary ability is an uncapped category established by Congress, where the specific criteria for what counts as “extraordinary ability” is left to the executive. It does not require an employer-sponsor and gives recipients much more freedom to work, change jobs, or start new companies than other visas. An ambitious administration could use the discretion left by Congress to turn the O-1 into a visa program to rival the H-1B among the most talented people looking to come to the U.S. The administration should consider making it easier for startup founders to use the O-1, and broadening eligibility for people working in critical fields such as artificial intelligence.

The J visa for exchange visitors is another uncapped category ripe for additional executive reform. The Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs is empowered to determine valid exchange categories. The current list could be expanded to promote intellectual exchange in both academia and the private sector. Further, the executive branch could adjust the requirement that exchange visitors return home for two years after the end of their program. This requirement doesn't apply to visitors from countries that have decided to waive it, and the U.S. benefits when such visitors decide to stay. The executive branch could retain more exchange visitors if a government body with an interest in securing STEM talent in the American workforce (such as the National Science Foundation or the Department of Defense) established objective eligibility criteria for J-1 holders to apply for an Interested Government Agency Waiver.

The H-1B is the biggest high-skilled program in the United States, and it too has significant problems that could be addressed by executive action. This year, employers filed nearly 500,000 petitions for 85,000 H-1B visas. Instead of allocating these scarce visas to the most valuable talent, USCIS runs a lottery in which world class experts have essentially the same chance of winning as entry-level IT workers. The lottery was established by USCIS, not Congress, and replacing this system has bipartisan support — the Trump administration attempted to replace it by executive order and it featured in a Biden campaign promise. While Trump’s attempt was ultimately struck down by the courts, it was for procedural reasons (it was an action taken by an unlawfully sitting DHS Secretary) and not on the merits of the proposal.

Executive actions naturally carry some risk both from the courts and from future administrations. In theory, Congress could of course pass any of these reforms without such risks and without the policy design constraints inherent to executive action. Nevertheless, executive action is still very promising given the large improvements to high-skilled immigration it affords in the absence of congressional movement. Further, because high-skilled immigration is perhaps the least polarized corner of immigration, executive reforms are likely to endure across changes in administration.

Better sooner rather than later

Given all the options for high-skilled immigration reform and the increasing momentum in DC, major changes are now within the realm of possibility.

As Senator Maria Cantwell, the chair of the Senate Commerce Committee, told Politico recently, “I think the question is whether you do [high-skilled immigration reform] now or in 10 years. And you’ll be damn sorry if you wait for 10 years.”

Let’s not wait.

Great article, don't disagree with a word.

"A majority of Americans (66%) say they would prefer to either increase the rate of immigration or keep it the same, according to Gallup. A minority — 31% — want to decrease it."

This is misleading framing.

The percentages from the poll are 31% less, 33% more, 35% same.

You could just as easily say "64% want less or the same amount...and only 33% want more."