The Afghanistan occupation and the Japan occupation

We learned the wrong lessons from our post-WW2 success

Everyone is talking about the Taliban’s swift reconquest of Afghanistan in the wake of the U.S. withdrawal. As usual, most Americans understand this event only through the lens of their domestic political viewpoints. Conservatives who just a few years ago were praising Trump’s new “America first” attitude and his withdrawal from Iraq are now wailing that Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan is the sign of a dying, decaying empire (that can of course only be restored by a conservative return to cultural and electoral dominance). Some on the left are decrying the U.S. “defeat”, raising the question of whether they think we should have continued occupying Afghanistan forever in order to secure “victory”. Others on the left are bewildered, bereft of talking points except to call for accepting a bunch of Afghan refugees (which of course is something we really ought to do).

Americans are approaching the situation this way because America is an insular country. Americans are among the least likely people to travel abroad, and our foreign language ability is among the world’s worst. Even our economy is unusually closed. When asked to identify Iran on a map, here is how Americans responded:

I’m just sad they didn’t include the Western hemisphere on the map. Anyway, you get the point.

I’m no foreign policy expert, but I have lived overseas (about 4 years in Japan). That experience taught me how insular my own views of the world had been, and gave me a desire to bring the same perspective to my fellow countrymen. Realistically, though, this won’t happen, so instead all I can do is offer my thoughts on a blog.

Basically, my thought is this: Military occupations are much less able to transform countries than Americans tend to think. In particular, we should never go into a war expecting the outcome to look like post-WW2 Japan.

The Afghanistan War

I supported the Afghanistan War in 2001. I’m not a military interventionist in general — I strongly opposed the Iraq War just two years later, and protested against it. But in 2001, the case for war in Afghanistan seemed strong. America had suffered a huge, devastating attack on our territory; the terrorist group who perpetrated the attack was still at large; the Taliban government of Afghanistan was sheltering those terrorists. The case for war, as I saw it, had nothing to do with the odious nature of the Taliban regime — there are lots of odious regimes in the world, and we don’t go invading them just because they’re nasty and bad, nor should we. Instead, it was about eliminating a clear and present threat to the United States, and about punishing those who had been responsible for it.

Ten years later, that case for war still seemed strong. Bin Laden slept with the fishes. The leadership of al Qaeda had all been killed or captured, except for Ayman al-Zawahiri, a cranky old man who we seemed to leave in place in order to alienate as many people as possible before al Qaeda finally slipped into the history books. Though no one will ever say al Qaeda is dead, the centralized, competent organization that attacked us on 9/11 is certainly gone, and the name is now basically just a franchise used by a ragtag bunch of scattered local Islamist gangs who usually lose the wars they’re fighting in. Mullah Omar, the Taliban leader who chose to shelter and support al Qaeda, bought the farm in 2013 (though we didn’t know it til 2015).

In other words, America did what I saw us as having come to do. The threat (al Qaeda) was eliminated, and the punitive expedition seemed to have inflicted sufficient punishment on the people who sheltered them. Accordingly, the U.S. began to draw down troops, and by 2015 our military presence in the country was relatively minor.

At no time did I believe that U.S. military occupation would transform Afghanistan into some kind of liberal democracy. My belief was not due to any deep knowledge about the country itself; just reading a bunch of news articles and talking to a few Afghan doctors I knew in Japan. My impression was that this was a poor landlocked country surrounded by other poor countries, whose economy was based mainly on opium. Additionally, it seemed like a violent tribal society, where the only authority able to impose real order in the past few centuries was the Taliban. Furthermore, I understood the Taliban to be an ethnic militia, representing the Pashtun group who comprised the largest single ethnicity in the country. Given that, it seemed inevitable that Afghanistan would never become a stable liberal democracy, and that the Taliban would be back as soon as America left.

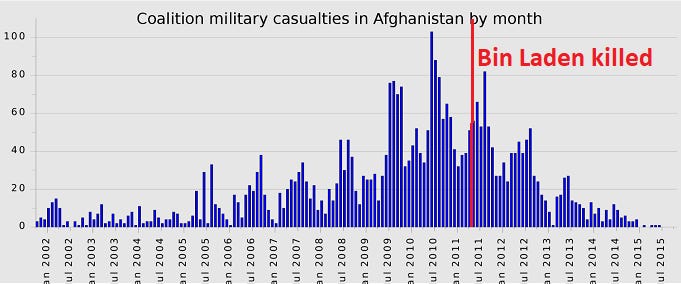

It turns out I was right. The U.S. troop drawdown wasn’t accompanied by Taliban advances or victories; indeed, U.S. casualties dropped to a very low level:

It seemed incredibly unlikely that this was due to a radical diminution of Taliban military capacity; instead, the Taliban were simply waiting for us to go away. Indeed, they were negotiating with us for us to go away, and even fighting alongside us against ISIS. It seemed inevitable that soon we would withdraw troops, the Taliban would take the reins of power again, and that they had learned their lesson not to harbor anti-U.S. terrorist cabals. The punitive expedition was complete, and now the country would go back to its natural rulers. Staying in the country past 2013, it seemed to me, was a mistake — an example of sunk cost fallacy, and a political problem where neither Obama nor Trump was willing to endure the public image fallout of seeing the U.S.-backed puppet government fall on his watch. Better to get it over with.

Biden saw things the same way I did, and here we are.

Of course, lots of people are saying that the U.S. was “defeated” in Afghanistan — as if permanent occupation would have represented some sort of “victory”. Of course, various people have their own political B.S. reasons for saying that the Afghanistan war represents a failure or defeat. But I also think there’s a popular idea that U.S. military occupations ought to be able to transform countries into prosperous stable liberal democracies. That idea is nuts, and it represents us learning exactly the wrong lessons from the resolution of World War 2.

The occupation of Japan

Japan in 1944 was a fascist empire, committing war crimes throughout the Pacific. Today it’s a rich peaceful stable liberal democracy (and a U.S. ally). How did that happen?

To many Americans, wrapped up in their insular worldview, the answer is simple: U.S. occupation transformed the country into what it is today. Take a fascist dictatorship, add some U.S. soldiers, and shazam, rich liberal democracy! So of course the fact that we can no longer seem to pull off this sort of trick means that we’re a fallen, diminished empire and blah blah.

In fact, the U.S. occupation did transform Japan in some important ways. The norm of civilian control, which Japanese people now highly value, was probably cemented due to a long period of U.S. insistence that the military (now called the Self Defense Force) stay out of politics. Douglass MacArthur did implement a program of land reform that made the country more equitable and probably more prosperous.

But the degree of U.S.-driven transformation is vastly overstated. First of all, although the U.S. executed a number of Japan’s wartime leaders, the people who eventually took power were all from that same group of people; there was no thorough political cleansing of the country. One of Japan’s most notable postwar prime ministers, Kishi Nobusuke, was a class A war criminal and former administrator of occupied Manchuria, known as “the Monster of the Showa Era”. Along with some other war criminals, he was among the creators of the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which still rules to this day. He’s also Shinzo Abe’s grandfather. Many other postwar leaders have similar origin stories.

This is not to say that Japan remained fascist (as some left-wing commentators assert). It most obviously and manifestly did not remain fascist. Instead, various leaders who had earlier supported and even participated in fascism decided that liberal democracy was better for the country. One reason they made this decision is that the U.S. had just proven liberal democracy’s economic and military effectiveness by winning WW2. They almost certainly could have restored dictatorship in Japan — the U.S. was clearly willing to tolerate dictatorships among its Cold War allies in Korea, Taiwan and elsewhere — but they chose not to. Instead, they drew from a liberal democratic trend that had existed in Japan well before the military takeover of the 1930s.

Japan’s prosperity, too, was not handed to it by America. Yes, opening American markets to Japanese-made products (partly due to the Korean War) helped the country’s exporters refine their craft. But we’re talking about an advanced industrial society that had managed to develop military technology on a par with the U.S. before the war. Japan had always been intent on being an advanced manufacturing superpower, and its strong industrial policy had little to do with U.S. influence (though it was happy to import manufacturing techniques and technology from the U.S.). Postwar Japanese culture, too, demonstrated a smooth evolution from prewar culture in many ways.

And what about the U.S.-written constitution? Many Japanese people hold this document in high regard, and it’s filled with liberal democratic principles. But in practice, the government pretty much just interprets the U.S.-written constitution to mean whatever it wants, as when Japan’s Supreme Court declared that forcing women to adopt their husbands’ surnames was consistent with the constitutional guarantee of gender equality, or when Abe “reinterpreted” the constitution’s declaration of pacifism in order to allow the country’s current military buildup. These episodes and many others show that when Japan wants to be less liberal, the ghost of Douglass MacArthur has no power to stop it. Which means that the fact that Japan is still quite a liberal nation (and in many ways more liberal after Abe than before!) is not due to American power, but to the country’s own choices.

In other words, modern Japan is a prosperous stable liberal democracy not because of the magical transformative power of U.S. boots on the ground, but because of deep-rooted institutional, political, and cultural forces that were present before the war. The experience of conquering and losing an empire, and of fighting and losing WW2, deeply influenced Japan’s leadership and prompted them to choose the country’s modern course. But that’s not a transformation that the U.S. could have brought about if the country hadn’t had a leadership that both wanted this transformation and was capable of bringing it about.

Like I said, I don’t know as much about Afghanistan, but I assume that like pre- and postwar Japan, it has a dominant political faction that is both capable of governing and has the grassroots support to stay in power. That faction is the Taliban. Unlike in Japan, that faction has neither a history of successful industrialism nor a tradition of liberal democracy to draw on. And unlike in Japan, that faction has no qualms about maintaining its power through the most violent of means. And unlike in Japan, that faction has not recently experienced a catastrophic failed war of conquest that persuaded it to pursue a course of peaceful stable economic development.

Military occupation was simply never going to make Afghanistan into Japan, because military occupation wasn’t what made Japan into Japan.

America is not an empire

Learning the correct lessons from World War 2 means dispensing with the fantasy that American military occupation can have magical deep transformative effects. It did not in the Philippines, it did not in Vietnam, it did not in Iraq, it did not in Afghanistan, it did not in Japan or Germany. Nor should we expect it to.

That doesn’t mean military occupation never has transformative effects on a society, or that it can’t. There are many cases of empires that utterly transformed the societies they conquered. The reason America doesn’t transform places through military occupation is that in many ways that matter, America is not an empire.

One common hallmark of empires is settler colonialism — i.e. sending a bunch of your people to settle the places your army conquers. America used to do this, which is how we got this big land mass; China still does it. But we stopped doing it at some point; you didn’t see Americans moving en masse to settle the Philippines, Vietnam, or Iraq. That assured that those places would never become part of America.

Even when they don’t do settler colonialism, empires generally work to integrate their conquests into their economy, as Britain did with India. The U.S. doesn’t really do this either; the occupied Philippines was always a glorified military base, and Vietnam and Afghanistan were cases of temporarily propping up local puppet governments for the purpose of fighting a war against a bigger enemy (the USSR or al Qaeda). We didn’t economically need Afghanistan or Iraq or Vietnam or the Philippines etc. When Japan and Germany did integrate their economies with ours in order to help themselves develop, it provoked an American backlash!

The flip side of American insularity — what makes it partially a virtue rather than purely a vice — is that it means we don’t really want to conquer other places. We have no use for them economically; Americans are divided between protectionists and free traders, but there’s no real constituency for colonially managed extraction. Nor do we want to move to conquered places; to the extent Americans want to move anywhere other than their hometowns, it’s to hip American coastal cities.

In the decades since the Iraq and Afghanistan wars began, it has become fashionable for Americans to call their country an “empire”. I blame Karl Rove and the neocons. Instead of viewing Afghanistan as a punitive expedition and Iraq as a failed politically-driven misadventure, we decided to accept the mid-2000s CNN conceit that America Is An Empire Now, as if we had somehow gone through some deep fundamental transformation and emerged as post-Caesar Rome. Neocons thought being an Empire sounded exciting and cool. Leftists thought America as an Empire provided the perfect villain for their narrative of anti-capitalist liberation. Foreign policy scholars and pundits loved the intellectual exercise of fitting America into a historical continuum of empires. Normal Americans simply didn’t care, absorbed as they are in their eternal local culture wars, and so accepted the pompous new terminology uncritically.

But it was just never true. America is not an empire, but a nation-state — an insular, self-centered nation state, sometimes a militaristic and aggressive nation-state, but not the kind of entity that seeks to incorporate new territories and new economic satrapies.

And we would do well to remember this. Our foreign policy should be based on our fundamental character as a nation-state rather than an empire. We should be willing to help defend our friends from aggression, and from the encroachment of true empires, but we should not occupy and seek to transform other countries. That is simply not what we do. Hopefully Afghanistan will serve to remind us that that is simply not what we do.

One primary bad assumption about the mission in Afghanistan is that there is some fundamental need for Afghanistan to exist as a single country, that these colonial borders should be maintained at a great cost in human life. The ruling group you mentioned in Japan shared a culture, language, religion, and ethnicity with a majority of the country, although significant minorities existed (Okinawan, Ainu). In Afghanistan, things are much more divided. Would the Tajiks be better served as part of Tajikistan? Would the Persian speakers be better off with Iran? Would they at least be better off separate from the Pashtuns in three countries? Is it fair to expect a fledgling government to solve the complex Sunni/Shia divide?

The fact that we go in there expecting new states that are still figuring out how to collect taxes to solve difficult problems of protecting minorities that remain challenges for advanced states seems so unrealistic it is hard to believe it is possible. However, I don't think we had to settle for letting the Taliban rule over everyone. We failed on this with the Kurds in Iraq, and expected their new democracy to solve the Sunni/Shia problem. Somehow we found peace in Yugoslavia, by getting every group their own country. Why don't we try this approach more often?

I know little about this part of the world, but my son is far more knowledgeable and felt I should offer an alternative view on some of your propositions:

Thanks for the interesting read, Noah. On the two main points – that American military presence does not magically make countries more like America, and that the reason post-war Afghanistan does not resemble post-war Japan is primarily due to local factors – I agree, but I think there are some important misreadings of the situation.

Primarily, the idea that “… the only authority able to impose real order in the past few centuries was the Taliban” is factually wrong, deeply patronising, and promotes a misconception that ultimately serves to excuse America from blame for the outcome. While the name ‘Afghanistan’ is comparatively new, the part of the world to which it refers, historically known as Khorasan, has been well-run for much of its history. Over the past few centuries alone, the Shaybanid Khanate (based in modern Uzbekistan), the Safavid Dynasty of Persia, and the local Durrani Shahs have all been competent and effective rulers of the territory; the cities of Kabul, Herat, Balkh, and Mazar-e Sharif have been cultural centres for centuries.

Even in the 20th Century, the period from the end of the First World War to the very late 1970s was marked by stability, rising prosperity, and integration into global society; while rural areas may have been conservative in habit, as rural areas almost universally are around the world, society as a whole was generally open and becoming steadily more so. Anarchy and misrule has been the historical exception, rather than the rule, and usually occurs on the border with foreign states (like the Raj, or the Sikh state in the late C18 to early C19) or in response to foreign intervention that disrupts local patterns of authority. While Afghan society and its power structures are certainly nothing like Japan’s, and may be less familiar or accessible to outsiders, Afghanistan is not historically ungovernable.

There are some other issues (the term ‘tribal society’ obscures a lot of complexity, and the identification of ‘empires’ with ‘settler colonies and population replacement’ is inappropriate and refers to only one of many possible models of imperial organisation and exploitation, to name just two), but most importantly, the excuse offered for the present outcome – that Afghanistan is simply historically ungovernable – is untrue, misleading, and serves to mask the many failings of the US in its Afghan adventures.