SVB and the Fed

Charting a course between inflation and bank failures.

The banking panic of 2023 appears to be over, as swiftly as it began. Just a couple hours after I published my last post, the government took decisive action to stop the crisis from spreading. It did two things:

It guaranteed all the deposits of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank (another medium-sized bank that failed), using something called the Deposit Insurance Fund. This is a government-mandated insurance fund paid for by other banks.

It created a program called the Bank Term Funding Program, which will lend a bunch of money to other shaky banks in case they need to get cash quickly to pay their depositors.

Silicon Valley Bank’s depositors are already able to access their money. The U.S. government works very fast, when it wants to.

This ended the panic. The stocks of other medium-sized regional banks went down on Monday, but there was no major wave of deposit withdrawals across the nation. Which isn’t surprising — this is exactly how economic theory says things should work. Once people know that they can get their deposits out of their bank regardless of what other people do, they have no reason to pull their deposits, and the panic ends.

This leaves a lot of loose ends to tie up and issues to mull over. For example:

Who will be able to access the Deposit Insurance Fund? Does this mean all uninsured deposits are now de facto insured? If so, how long will that last?

Will there be any new regulation on medium-sized banks, to go along with the implicit deposit guarantee? Should there be?

Was this a “bailout”? Does it matter?

What will be the long-term effects of this episode on the relationship between the U.S. government and the VC/startup industry?

Those are all important questions, and I’ll write posts covering all of these things. But today I want to focus on one very important loose end: the implications for interest rate policy and the macroeconomy.

Banks were in danger because interest rates went up

The first key thing to understand here is why the government acted so quickly and decisively. The key here is that the banking panic really did have the possibility of spreading beyond SVB, and beyond the tech sector and California in general. This is from a (very good) Washington Post writeup on the crisis:

Over the weekend, [government officials] began to see banks outside of tech-heavy New York and California showing signs of volatility. Bank executives told federal officials that major customers had warned they would withdraw their money and move it to a Wall Street giant for safety first thing on Monday morning.

If it had just been a case of some panicky VCs spreading fear and confusion, the panic probably just would have stayed in tech-world like every other tech crash. But there was a reason the panic had the possibility of spreading. That reason was interest rates.

For 40 years, interest rates were basically a one-way bet. They just went down and down and down. The reason was that there was no inflation, so central banks kept lowering interest rates more in order to fight each recession, and then having little reason to raise them once the economy recovered. But then in 2021, inflation reappeared after a decades-long absence, and interest rates stopped looking like a one-way bet:

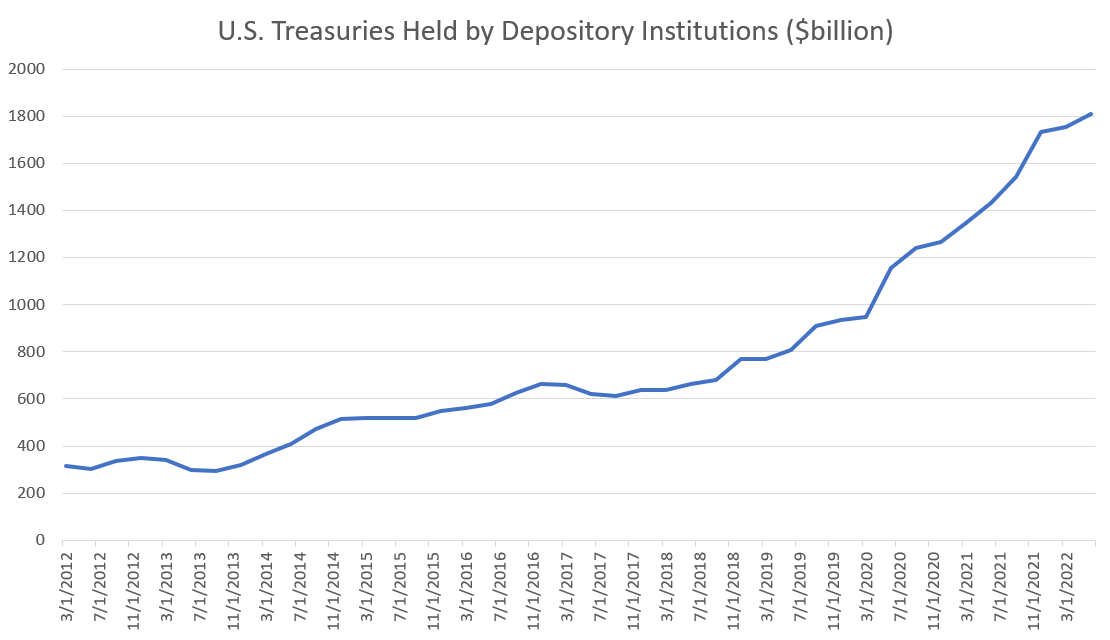

Surprise!! But by that time, banks had bought a ton of long-dated Treasury bonds and other long-dated government bonds. This made them vulnerable to a rise in interest rates.

The incomparable Matt Levine has a great writeup of why rising interest rates created problems for banks. I’ll just give you the short version. Banks borrow short to lend long; when depositors ask for their money bank, banks have to sell their long-maturity assets to raise cash to pay off the depositors. If the long-maturity assets have gone down in price, that reduces the amount of cash the banks can get by selling them. This makes them more vulnerable to a run.

When interest rates go up, the price of long-maturity fixed-rates bonds (for example, 10-year Treasury bonds) goes down. So the fact that interest rates went up meant that a lot of banks saw the value of their assets drop, making them more vulnerable to runs. That was why there was a chance of the SVB panic spreading beyond the tech sector. And that is why the government acted so forcefully.

Was it a mistake for banks to hold so many long-maturity bonds? Larry Summers says it was:

But I think Summers’ argument just doesn’t make sense here. Saying that borrowing short to lend long is “one of the most elementary errors in banking” is like saying that jumping out of a plane is “one of the most elementary errors in skydiving”. Without borrowing short and lending long, there really isn’t much of a reason for a bank to exist!

And if you’re going to borrow short and lend long, the U.S. government is basically the safest entity you can lend to. Treasury bonds are highly liquid (i.e. you can always find a buyer), you know exactly what they’re worth, the default risk is practically nil, and they’re not going to drop in price if you have to sell a bunch of them.

This is why a bunch of other banks throughout the land also have a lot of Treasuries. And it’s why, when the government pumped a ton of money into the economy during the pandemic, and people stashed that money in banks, the banks bought even more Treasuries.

And what this means is that the Fed, by raising interest rates, is reducing the value of banks’ assets, and thus is making our banking system less stable. Under normal circumstances, the Fed would respond to this week’s events by simply cutting rates — just like it did for 40 years. But there’s a reason it can’t easily do that this time — inflation hasn’t gone away.

Inflation just isn’t going away

As it happens, inflation numbers just came out. Core inflation, which is what the Fed targets, is still around 5.5%, whether measured month-over-month or year-over-year:

As usual, I recommend Jason Furman’s monthly thread for a good update on various alternate measures of inflation:

You can see that inflation has come down substantially since mid-2022. That partial victory is due to a combination of the demand-reducing effect of the Fed’s rate hikes, and the supply-increasing effects of lower oil and gas and food and shipping costs.

But the partial victory is only partial; inflation is still well above target. That’s going to keep making people mad because it puts downward pressure on their real wages and incomes (for reasons economists don’t entirely understand). But even more significantly, it means the Fed is in danger of losing its credibility.

Central banks live in terror of losing their credibility. If people believe that a central bank isn’t willing to do whatever it takes to keep prices from spiraling out of control, then they’ll raise their prices, because they think everyone else is going to raise their prices, and the central bank won’t act to stop the madness. So then when the central bank finally decides that enough is enough, it has to raise rates far more — and cause far more damage to the economy — just to convince everyone that things have changed and the hawks are once more in control.

The Fed really, really doesn’t want that to happen. And every month that inflation stays at 5.5% tends to cement 5.5% as the new normal — and to convince the American business world that the Fed doesn’t really mind 5.5% that much. Thus, the Fed has a good reason not to let inflation linger there for a long time.

Are we now living under “financial dominance”?

So this puts the Fed on the horns of a dilemma. If it keeps raising rates, more things will break in the financial system. Bank balance sheets will get weaker, putting them in more danger of bank runs like the one that just happened to SVB. But if the Fed pauses its rate hikes or cuts rates to ease the pain in the banking world, it runs the risk of losing its credibility and letting inflation go out of control, necessitating even bigger rate hikes and even more pain in a few years.

This is just the normal inflation-unemployment tradeoff, but with a financial angle thrown in. Bank weakness is bad because it causes banks to pull back lending, thus reducing growth and employment. Bank failures are bad for the same reason, only more so. But banks also have a lot of political clout, and banking panics are seen as huge public relations disasters for the government — as are bailouts, when those become necessary to stop a panic.

We might call this situation “financial dominance” (echoing the term “fiscal dominance”, which is when the central bank can’t raise rates because it’s afraid of making it hard for the government to pay the interest on its debt). Some economists think financial dominance is already making the Fed slow down its rate hikes:

There’s also the question of whether the Fed’s new Bank Term Lending Fund will be a sort of backdoor monetary easing that actively counteracts rate hikes. The BTLF will loan money to banks to help them pay depositors out in case of a run. But the knowledge that they’re now run-proof could make banks lend money more aggressively — which would push up demand, and therefore push up inflation.

To sum up, SVB made it very clear to the Fed that fighting inflation will also break things in the financial system. The hope is that regulation and special pro-stability measures will be able to shore up the banking system while letting the Fed continue to hike rates and reduce aggregate demand enough to quash inflation. If that hope fails, then we will face some difficult and painful choices with no great outcomes.

Update: My friend Balaji Srinivasan says that “the Fed caused the banking crisis” via higher interest rates. It’s true that inflation-fighting efforts made banks more vulnerable, yes. But Silicon Valley bank and the crypto banks (Signature and Silvergate) were vulnerable not just because their government bonds declined in value, but also because they took lots of uninsured “jumbo” deposits from very risky depositors (crypto people and startups). That was a risky business model. In fact, as Matt Levine has pointed out, it was doubly risky because the two risks were correlated — higher interest rates cause crypto to crash, and they also dry up VC funding and force startups to use their cash deposits to make payroll, in addition to lowering the value of Treasuries and other bonds. So SVB and the crypto banks were taking a lot of risk on top of standard interest-rate risk, which is why they were the first banks to fail.

Also, Balaji is very wrong to say that U.S. government bonds were “the riskiest” bet you could make. In fact, Treasuries are safer than any other fixed-rate bond of similar maturity. (You can make floating-rate loans, but those are risky in a different way). Treasuries are subject to interest rate risk, as any first-year finance class will teach you. But their risk of default is the lowest. If you’re going to borrow short and lend long, Treasuries are the safest thing you can buy. (And if you’re not going to borrow short and lend long, why are you a bank in the first place?)

Update 2: Banks in other countries are also experiencing fragility, showing that the difficulties resulting from the new inflationary era and the accompanying rate hikes are not limited to the U.S.

The problem for these smaller banks isn't just that interest rates went up. It's that they had a flood of deposits when interest rates were extremely low, mainly due to the various stimulus programs. The smaller banks couldn't grow their loan portfolio at a comparable rate to the increase in deposits so they had to buy more bonds. Then with swollen bond portfolios, rates went up causing large unrealized losses and at the same time, deposits were shrinking as the excess cash was disappearing. SVB is an extreme version of this story but I've been hearing about community banks feeling this funding stress since last fall.

I can't see how the FDIC can make a credible commitment not to bail out depositors in future (they didn't bail out Indymac, but that brief period of bravery ended with the GFC). So, it would be better to make the guarantee explicit, and regulate accordingly (roughly, turn them into public utilities).