Status Anxiety as a Service

The toxic social dynamics of Twitter

Two years ago, my friend Eugene Wei wrote a blog post called “Status as a Service (StaaS)”, which laid out what has become the canonical framework for thinking about social media. Eugene basically divides social media’s function into three dimensions — utility (i.e., direct usefulness), entertainment value, and social capital. He spends much of the post discussing the third of these — the way social networks create new ways for people to gain status and respect. Get the most Twitter follows, or the most Facebook likes, etc., and you’re somebody. Social media has democratized celebrity; anyone can be an influencer.

Anyone, but not everyone. Just as most people can’t become Hollywood stars, most people can’t become social media influencers. But unlike in the old days, when people would obsess over Hollywood actors from afar, nowadays social media allows people to come in contact with their heroes directly. And no network facilitates this more than Twitter.

I continue to believe that Twitter, alone among all social networks created thus far, represents something truly new under the sun. Facebook and LinkedIn more-or-less preserve the networks of personal friendship, hobby interest, and professional networking that exist offline. Instagram maintains the celebrity-fan dynamic, with influencers dominating their pages at an Olympian remove. But on Twitter, anyone can talk directly to anyone at any time, and, short of blocking them, the person they’re talking to can’t stop you from talking to them.

On other social networks, if you created a post, you can delete comments that you don’t like; you are the moderator of your own threads. But on Twitter you can’t. There is a “hide replies” function, but it just sends the replies to a special “hidden replies” section where anyone can peruse them at will. Even if you block someone who replies to you, their reply-tweet remains.

These two quirks of Twitter — free direct communication and almost no ability to regulate replies — make all the difference. Suddenly, people can talk directly to any celebrity, any politician, any journalist or activist or influencer of any kind. And the person they’re talking to can’t stop them.

Eugene sees Twitter as basically a competition to get the most follows and the most likes/retweets:

Early Twitter consisted mostly of harmless but dull life status updates…What changed Twitter, for me, was the launch of Favstar and Favrd (both now defunct, ruthlessly murdered by Twitter), these global leaderboards that suddenly turned the service into a competition to compose the most globally popular tweets…What Favstar and Favrd did was surface really great tweets and rank them on a scoreboard, and that, to me, launched the performative revolution in Twitter…

We are now in late-stage performative Twitter, where nearly every tweet is hungry as hell for favorites and retweets, and everyone is a trained pundit or comedian. It's hot takes and cool proverbs all the way down.

This aspect of Twitter certainly exists. But I think it leaves out something important — the status-conferring role of reply-tweets, and the social role of the people who write them. Reply-tweets very rarely go viral — they have almost zero chance of conferring the kind of clout Eugene describes — but people spend much of their time on Twitter replying to the things they read.

Being able to reply to high-status people, whether they want you to or not, is a heady status-conferring experience. You can say mean shit to the most famous Hollywood movie star, and there’s nothing he can do about it. Or you can say something nice, and hopefully get a reply or a shout-out. This puts you on a plane of near-equality with people who otherwise tower over the social landscape.

Near-equality, but not equality! Chris Pratt may respond to you on Twitter, but at the end of the day he’s still Chris Pratt and you’re not. A 20-follower account might successfully dunk on a 200,000-follower account, but at the end of the day one has 200,000 followers and the other has 20.

This can be maddening. Twitter creates the instantaneous illusion of social equality between influencers and normal people, but then it periodically reminds you that it’s an illusion. When you’re in the replies, giving hell to a famous person who made a bad take or having a conversation with your hero, it seems like a radical leveling of human society. But as soon as the reply-thread is over, the high-status person simply sails back off into the high-status clouds, and you crash back down into the low-status muck.

That process, which repeats itself many millions of times every day, creates some very unusual social dynamics. For example, there’s “the ratio”, in which a mob of reply-tweeters try to leave someone with more replies than likes. It feels heady to be part of a ratio-mob, as evidenced by the people who reply with “just here for the ratio”, or who re-state a rebuttal that many others have already made. (Some people have invented a second type of “ratio” that doesn’t depend on being part of a mob: writing a reply-tweet that gets more likes than the original tweet it’s replying to. I’ve seen Zoomers in group chats bragging about the famous people they managed to “ratio” this way.)

There’s also a strange dynamic between large and small accounts (defined by number of followers). One time a random guy showed up in my mentions and started saying abusive things, but when I responded in kind, he seemed genuinely shocked. He told me that as a big account, it was my responsibility to let small accounts like him “keep me honest”. I.e., he viewed it as my social role to quietly accept whatever abuse he decided to fling my way, with the understanding that it was compensation for the difference in social status that our follower counts conferred.

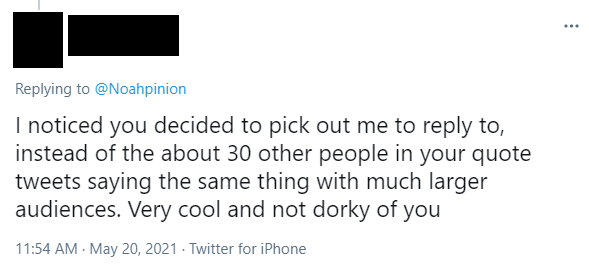

In fact, another example of that happened recently. I responded to some random guy to laugh at how “dorks” had taken a joke tweet of mine seriously, and he wrote:

This unspoken social rule seems driven by Twitter’s unique creation of momentary status-equality illusions. Low-follower folks want to preserve the feeling of sudden elevation they get from dunking on a big account; if the big guy returns fire, it’s a brutal reminder of how fake that moment of equality really was.

Finally, there’s the social dynamic of “blue checks” — verified accounts. For a long time, Twitter paused verification for almost everyone, so the blue checkmarks became an artificially scarce commodity. And though blue checks are nearly useless in terms of actual Twitter functionality, their artificial scarcity creates a status difference between those who have them and those who don’t. And that leads to a sort of class consciousness on Twitter — a resentment of “bluechecks”, and a characterization of them as aloof, self-important, and shallow. If you don’t believe me, just search for the word “bluechecks” on Twitter and scroll down for a bit. You’ll see.

Anyway, my hypothesis is that by bringing people much closer together in social status, Twitter emphasizes the intractable gaps that remain. And this creates constant status anxiety among some Twitter users, who feel a constant need to come back to the app in order to find bluechecks or big accounts to take down a peg — or to assist one big account in taking down another. The constant parade of hot takes that Eugene describes is only half of the Twitter equation; the never-ending search for ratios and dunks is the other half.

And that’s very important for Twitter’s business model. It usually takes a long time to build up a big following (my 200k followers, a number on the smaller end of “big”, were accumulated over the course of a decade). Even a viral hit tweet doesn’t raise your follower count that much. And what qualifies as a “big” account keeps increasing as the platform ages; six or seven years ago, 200k would have been a huge number of followers, but now it’s only OK, since so many other people have now reached 500k or more. In other words, the more years Twitter exists, the more years of each person’s life would be needed to build up a large amount of social capital on the platform.

That means that for most people, becoming a big account is simply out of reach; they need something else to keep them coming back to the app. For many, that thing is status anxiety. Twitter isn’t just Status as a Service — it’s Status Anxiety as a Service. StAaaS, if you will.

As Twitter ages and the distribution of status gets even more frozen in, Twitter will have to rely on status anxiety more and more to keep new users engaged. That will exacerbate the toxic dynamics of Twitter, where every statement is willfully misinterpreted, humor is nigh-impossible, and bad-faith attacks are the universal norm.

Of course, Twitter’s corporate overlords know that their platform is like that, but they’re somewhat stuck. They want to make their product less toxic, but they also want to make money, and they’re not quite sure which changes would make people start quietly abandoning the app for lack of interest. They’ve tinkered around the edges of the basic formula — adding a “hide replies” function, letting people write tweets that you can’t reply to (but which you CAN quote-tweet and dunk on), hiding some reply-tweets below a fold, and so on. Now they’re opening verification back up to the masses, taking away one reason for popular resentment.

But they’ve never taken the crucial step of allowing people to actually drop reply-tweets from their threads or untag themselves from other people’s tweets. Doing that might make Twitter a lot nicer of a place, but it would put bluechecks and big accounts and celebrities at a more Olympian remove from the hoi polloi, which would end up actually reducing their status anxiety.

Thus, Twitter will continue to be the place where Americans go to scream at strangers — where status is conferred not just by little snippets of viral pseudo-wisdom, but by the ability to ridicule and attack those snippets. We should probably think long and hard about whether it’s a good idea to have our public discourse dominated and directed by a platform with that basic dynamic.

This is certainly true, but when I read this I wonder what share of Twitter it represents. Quite a few people, I’m sure, use Twitter not as a status machine, but as a genuinely unique way of finding interesting comment, information, references. This leads to a « quiet » Twitter life made of likes, quote tweets, the occasional reply or thank you note, but this apparent quietness should not mask the immense value of Twitter for these users.

One thing that might be useful is a downvote button, like with Reddit. If I see something on that site that I thinks is stupid or harmful, I don't have to engage with it or let it fester in my brain. I can just downvote and move on. On Twitter, I'm incentivized to engage with content that I think is bad, thus raising its profile and creating a more toxic environment. This doesn't directly get at the zero-sum social climbing that you're talking about, but it could help quiet down the atmosphere of encouraging rancorous discourse.