Should the U.S. increase or decrease defense spending?

It's not as simple as "guns vs. butter".

In a post last week about the future of military technology, I chided those who call for cuts in U.S. defense spending. I argued that it’s a politically bad look to slash military preparedness at a time when totalitarian superpowers invading and massacring their neighbors. And I also argued that since military tech is changing so fast, we need to be ready for anything, which requires putting dollars into more different technological baskets.

That message did not sit well with everyone. Judd Legum, who wrote the blog post I had criticized in passing, tweeted the following:

I reiterate my belief that in terms of the political optics, this is a particularly bad time to be calling for defense budget cuts. It’s one thing for leftists with no real power to call for defunding the military — after all, seeking a diminution of U.S. power is their whole shtick. But for mainstream progressives to call for defunding the military seems like a bad look at the precise moment when great-power conflict has reared its head again. If the purpose of the U.S. Armed Forces isn’t to help guard the world against the likes of Vladimir Putin, then what is it? (To say nothing of the fact that the military is the final guardian against any potential future Trumpist coup!) And with Biden calling for increased defense spending, it’s clear that progressive rage is going to be utterly futile anyway. Why should progressives waste their breath on a doomed effort that makes them look bad?

But OK. I am not a popularist; I think policies should be defended on their merits. People calling for defense budget cuts should not be shouted down or smeared as weak or unpatriotic. Legum’s questions about the proper size of the military budget, and the opportunity costs, are perfectly reasonable, so it’s good to discuss these issues. I’m not a military expert, but I’ll try to sketch out how I think about defense spending.

Guns vs. butter: The opportunity costs of defense spending

Economists have a standard way of thinking about military spending, which you’ll find taught in most 101 classes. It’s called “guns vs. butter”, and it basically just says there’s a tradeoff between using society’s productive power for military goods vs. consumption goods:

This tradeoff is certainly real. During World War 2, we shifted massively in favor of “guns” — GDP soared but consumer spending fell.

Progressives often seem to think in terms of this guns-vs.-butter model. All my life I’ve been seeing arguments like this:

It’s especially galling to see Congress eagerly embrace defense spending increases at a time when Republicans and Joe Manchin successfully used inflation as an excuse to cut off the child tax credit, send millions of kids back into poverty, and kill off Biden’s ambitious climate change agenda. If we didn’t have money for poor kids and staving off environmental catastrophe, how do we have money for fancy new weapons?

I’m galled by that too. I’m incredibly frustrated that the CTC and Build Back Better were cancelled. It’s especially annoying that inflation was used as an excuse, since the Build Back Better bill wouldn’t have contributed significantly to inflation. But I don’t think defense spending is to blame here; we didn’t choose guns over butter, we simply chose “no butter”.

One way to see this is to look at how much less of our economy we spend on defense than we used to:

In the Korean War, which was nowhere close to as big as WW2, we spend over 13% of our entire GDP on the military. In Vietnam is was 8-9%. Reagan’s famous Cold War defense buildup was 6-7%.

In comparison, we now spend less than 4% of GDP on the military. Biden’s $813 billion request would actually represent a slight decrease from the Trump years — less than 3.5% of our >$23 trillion GDP. Defense budget critics like Judd Legum tend to look only at the headline numbers; instead, they should look at the share of GDP, because that represents the fraction of our resources we’re diverting away from other uses.

In other words, defense spending consumed a much higher fraction of our GDP during the halcyon days of the post-WW2 decades — in fact, only for a few years during the late 90s did we divert less of our productive power to defense than Biden wants to do.

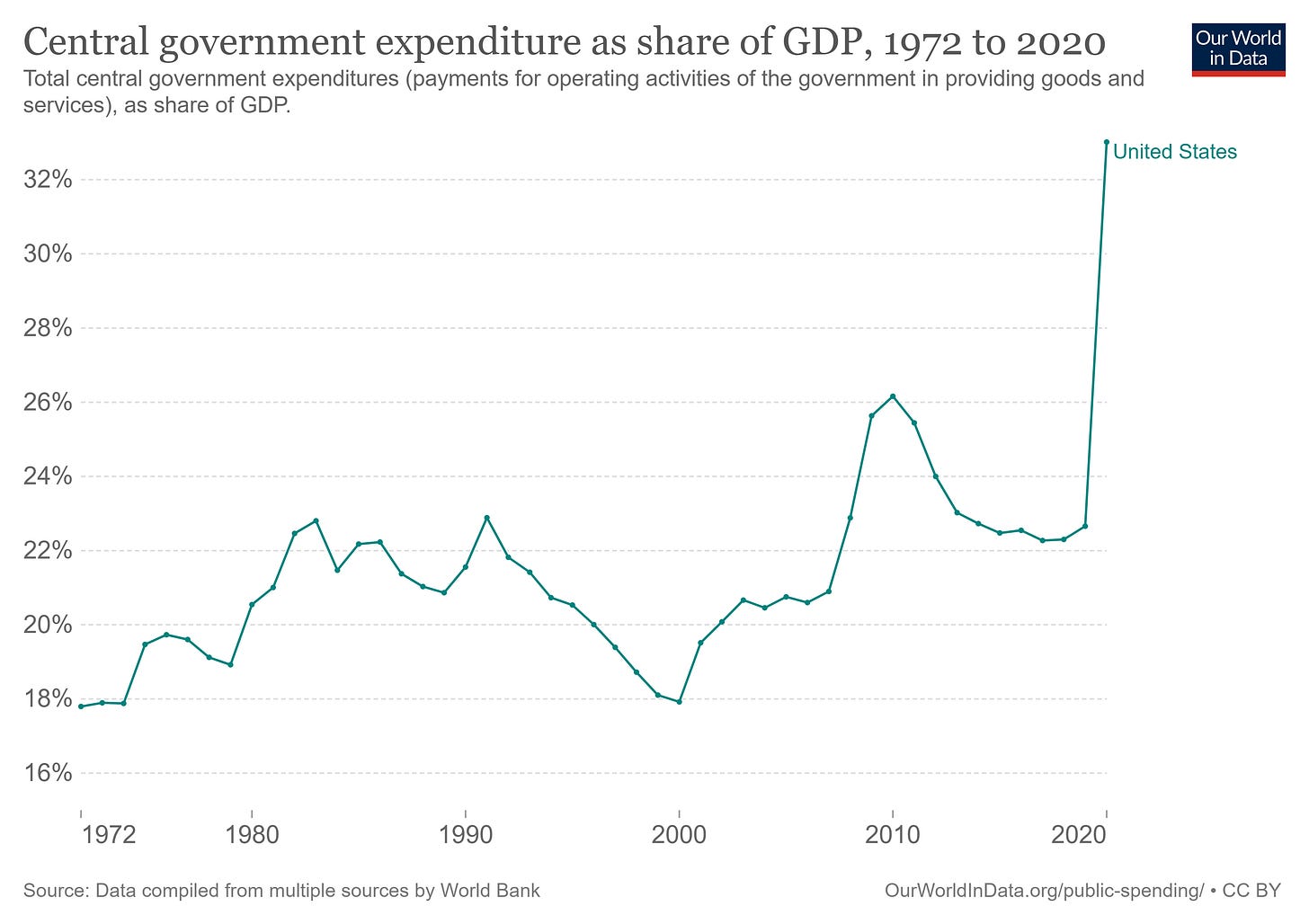

Now compare that to how much our government spends overall. Federal government spending as a share of GDP has generally risen over the decades, even as military spending has fallen:

So the fraction of our economy that the federal government spends on non-military stuff — i.e. “butter” — must be rising. Let’s look at what we spent money on in 2019 (before Covid spending took off):

Note that defense represents a pretty modest share here — about 15% of the total. Critics of defense spending like to trot out pie charts that show defense spending as a huge percent of government spending. But those pie charts only include discretionary spending, which is kind of a meaningless term here — it only means that we’ve decided to label most of our health and welfare spending “mandatory”. (Which sort of suggests that we value health and welfare spending quite a lot!)

Then there’s inflation to consider. Currently, consumer price inflation is running at about 7.9%. Biden’s $813 billion request represents a 7.9% increase from the $753 billion we spent in fiscal year 2021. In other words, Biden isn’t even asking for an increased defense budget in real terms — he’s asking merely to keep the military budget constant.

All this by itself doesn’t prove that $813 billion is the amount that we need to spend on defense. But it severely undercuts the argument that we’re depriving our people to pay for a big military.

How much gets wasted, and how do we cut the waste?

Another thing to consider is the common allegation that much of our military spending is wasted. In his post, Legum cites the notorious F-35 Lightning II, which went way over budget, costs a huge amount to operate, and has persistent problems with performance and breakdowns.

This is a big problem. Not only does the money wasted on the F-35 represent wasted resources that could have been used to buy food for hungry kids, but it points to serious undiscovered problems in our military’s actual fighting ability — perhaps not to the same degree as Russia, whose vaunted army is getting ground up by a much smaller and poorer opponent, but worrying nonetheless. I think you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone who’s happy with the way the F-35 program has gone.

But the next question is, how do we prevent such debacles from happening? Simply slashing defense budgets seems unlikely to do the trick, for the simple reason that the companies that were politically powerful enough within the DoD would have the power to keep their favorite programs going. You can see this in the history of the F-35 itself, which survived the steep cuts in defense spending during the Great Recession, waste and inefficiency intact. Instead, what would likely get slashed in a round of austerity would be smaller, more speculative programs — the kind of forward-looking, innovative things we need to stay ahead of China and Russia. Those Great Recession years saw us fall behind China in certain categories of advanced missiles, and we’re now racing to catch back up.

Another option is just to cut out expensive, fancy programs like the F-35 entirely. But it’s not clear what would replace them. Keeping up with China and Russia requires having fighter jets, and our allies need them too. It’s not clear what the alternative to the F-35 would be. Canada, for example, loudly announced that it wasn’t going to buy F-35s when Justin Trudeau took office. It instead held a competition to determine which fighter plane to buy, and recently settled on…the F-35.

So yes, we need to make sure that boondoggles like the F-35 don’t get repeated, but the answer isn’t to simply slash top-line budgets or to cancel any big new weapons programs. Instead, I suspect that the right move is to introduce more competition to defense contracting — intentionally reducing the dominance of a few big contractors like Lockheed Martin and Raytheon so that they can’t produce boondoggles without losing business.

What about just gutting general waste at the Pentagon? This sounds good, but the amount of such waste is probably not that big. A 2015 report estimated that the Pentagon wasted about $125 billion over five years. That’s a big-sounding headline number, but $25 billion a year out of a budget of $560 billion at the time is less than 5% of overall defense spending. It’s great to cut waste, but the opportunities for savings are relatively modest.

(Also note that when doing these analyses, progressives rarely if ever take into account the substantial boost to the private economy that comes from defense R&D spending.)

Anyway, the problem here is that progressives who want to cut defense spending are approaching it much as they’ve approached police spending — simply pointing at problems in the system and assuming that top-line budget cuts will solve the problem. That’s the same basic approach Republicans tried with welfare programs, and it simply did not work.

It’s a scary world out there

Of course, none of what I’ve said proves that $813 billion is the “right” number for defense spending. In fact, there is no such proof, because there’s no economic model that can tell you what the right amount of defense spending is. Note that this also means that the people who are calling for defense spending cuts have no idea whether $813 billion is the “wrong” number.

But we can talk about some general principles here. The basic reason for the U.S. to spend money on defense is to prevent the world from being dominated by Russia and China. The events of the past six weeks should clearly demonstrate that the era of great-power conflict has returned, that the consequences of simply rolling over for totalitarian superpowers are disastrous, and that the U.S. can play a positive and constructive role in helping the countries of the world defend themselves from invasion.

Critics of defense spending, including Legum, point out that we already spend a lot more than Russia and China do. Indeed, in headline terms, we do spend a lot more:

Some of this gap is overstated. About $50 billion of our defense budget goes to health care, for instance, and U.S. health care is notoriously overpriced compared to that of other countries. Our soldiers’ salaries are much higher too, simply because we’re a rich country.

That will explain only a modest part of the spending gap. Another part is explained by quality — the equipment and training the U.S. buys is often simply better than the equipment and training the Russians buy. As many military analysts have noted, this has taken a huge toll on the Russian war effort in Ukraine. To a large degree, it appears that militaries get what they pay for.

But “you get what you pay for” is kind of a weird reason to argue that we should be paying less, isn’t it? Skimping on things like hours of flight training didn’t make the Russians weaker on paper, but it did make them weaker in the field. When calling for budget cuts, we need to assess whether this would expose us to nasty battlefield surprises in the case of a conflict.

In fact, we’ll probably need to make sure our weapons systems are high-quality if we hope to match the sheer quantity that China is putting out. Observe the magnitude of China’s naval buildup:

Their ships aren’t as good as ours, of course, but again, that’s kind of an odd reason to argue that we should be spending less on ensuring that ours are of the highest quality.

As for what exactly we should be spending our military budget on, I am not a military expert. My instinct is always to spend as much as possible on research and development, and to diversify our spending among a whole lot of different programs that might come in handy in the case of a great-power conflict (just as we started spending money on radar, heavy bombers, and other next-generation weapons years before World War 2 broke out). My instinct is also that we should be spending money on the Navy, since Russia’s failures in Ukraine (and Europe’s increases in military spending) mean that China is likely to be our primary adversary in a great-power war.

That’s just my instinct, though. If you want to read more expert opinions, there are plenty of articles by advocates of higher defense spending, in which they list detailed priorities — to give just one example, see the recent article by defense policy analyst Kori Schake in Foreign Affairs. And of course read the arguments of experts who advocate cutting specific programs.

But keep in mind that the progressives calling for defense cuts are, generally speaking, no more expert than I am in the question of which military systems they need the most. They decry the waste of the F-35, but have no idea what should replace it in our arsenal. Really, they just see what look like big headline defense numbers, and react with disgust — without comparing those numbers to inflation or to GDP.

I don’t think this sort of analysis, or this sort of argument, is going to carry water with the general public. It’s unlikely to even carry water with the Biden administration. Yes, a lot of us are deeply frustrated and upset that Biden’s domestic agenda has been stymied. But the Pentagon just seems like the wrong target for that anger — especially right now.

I am writing this as someone who believes that we need to increase defense spending and also as someone who once worked for Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (in an administrative rather than a scientific area).

There is a difference between efficiency and effectiveness. Lawrence Livermore was high effective but it was never very efficient. It could get amazing stuff done quickly but as one researcher once told me -- cost doesnt matter. This is something that is important for the country and we will spend whatever it takes.

Its well to remember that the government doesnt do science all that well but depends on contractors. And anyone who has been through the challenge of Federal acquisition regulations knows that this is not a place for the uninitiated. On many occasions the government cant do business with the top contractors when such firms lack experience with federal acquisition.

When I worked at Lawrence Livermore, one of the many National Labs regulated by the Dept of Energy it eventually occurred to me that the Dept of Energy was basically a procurement agency. During those days I heard a joke about the 3 nuclear weapons labs managed by the Dept of Energy. It goes like this

When DOE say jump, Sandia says how high sir; Los Alamos says up yours, and Livermore within a few months puts together a $500 million jump management program

Very reasonable proposals. A reasonable defence budget is an entirely different thing from the galling refusal to approve the CTC and renovate America's aging infrastructure. They should be considered separately as Noah has chosen to do here.

Having said that, there is a lovely piece by Matt Stoller on TransDigm and other defence monopolies who obtain exorbitant contracts for sometimes basic military gear or push for expensive white elephant projects like the F-35.

So, until America fixes its monopolization in the defence industry and much else, a lot of that money will be going to tax havens and shareholders, which is a fine thing, but you can't do battle with a Caribbean trust.

The other thing is parallels to China and Russia are not exactly accurate. We have already seen that Russia is losing the war bot out of mediocre equipment but due to mediocre training, inefficient supply lines, and chip shortages among others. These are not problems the American army has. And to the extent that they have them, they are not problems that will be fixed by billions of dollars in budgetary allocation.

Getting the traditional basics right is way more important in wars than fancy gadgets, although few like to admit it.

With regard to China, it has traditionally neglected its military for sensible reasons. It is now building up rapidly. Again, it is not the situation the American army is currently in. There is more need for maintenance, I'd dare say, than growth.

What America needs is investment in technology - all kinds of technology. A DARPA-like project that is not controlled by private institutions who would simply lock it all up behind a wall of patents and who are more interested, as they should, in steady revenues anyway.

The amount of insights and innovation that will unlock will transform the defence industry and much else, faster and better than big routine military budgets.

Defence is a critical aspect of any nation. Pacifism is a lovely ideal in theory. Unfortunately, that is the extent to which its loveliness applies. But the fact that defence is critical, and even more so now, is not a reason to not spend wisely and be long sighted. It's a reason, the reason, to do just exactly that.