Noahpinion’s readership has grown a lot since I started this blog. There are a lot of posts that I wrote in the early days that I really liked, or which have strongly influenced things I’ve written since then, but which most of the current readers probably haven’t seen. So I thought I’d start occasionally re-upping some of my favorite items from the most distant parts of the Noahpinion archives, with some updates on how those posts have aged.

“I will never get to go to Hong Kong” was one of my first posts, about a trip I took to Hong Kong during the height of the protests there. Obviously the title is metaphorical; it’s about how the city’s unique culture was already being forcibly altered by relentless pressure from the CCP, a process that has only accelerated over the last three years. Hong Kong was a mainstay of the free world in the 80s and 90s — an exporter of widely beloved films and other cultural products, a place to do business, a unique global nexus of ideas and commerce. Seeing it so casually crushed, despite the population’s massive and desperate effort to preserve their way of life, was an experience that I must admit had a bit of a galvanizing or even radicalizing effect on me — and not just me either. It created in me the sinking certainty that if something wasn’t done, Hong Kong’s fate could befall more and more places.

I’ve been writing about China much more these past two years than I used to, and while the main reason is because of the big changes in the U.S.-China economic relationship, a part of it can be traced back to that experience in Hong Kong.

In October 2019, I went to Hong Kong for the first time. I had two reasons for going: First, because I had never seen the city, and it was one of Earth’s great legendary metropolises. Second, because Hong Kong was then in the middle of a wave of truly massive protests that had been going on for months, and threatened to change the city forever. I wanted to see the protests because they felt like history, and I wanted to glimpse the place itself before it changed.

I spent the first few days taking in the city, walking the streets, visiting the shops, guzzling dim sum and pu-erh tea, and waiting for my friend (let’s call him “BB”) to arrive. BB is a Chinese American who travels to Hong Kong fairly frequently, and had been to the protests before, and it was in part thanks to his stories that I had decided to go. Our plan was not to get involved; we sympathized with the protesters, but this wasn’t really our fight.

The first night my friend arrived, we went to a peaceful protest, with maybe a few thousand people, in a small urban park. I had heard that the HK protesters liked waving American flags, but to be actually confronted with thousands of people who still believed that my country stood for freedom was quite a shock.

As for the protesters themselves, they were the usual mix you’d expect in the U.S. — regular folks of all ages, mixed with a few young black-clad anarchist-looking types. Doctors got up and made speeches about what it was like helping save protesters on the front lines, even at the risk of their careers. The cops didn’t even show up.

The next day, however, is when things really kicked off. BB and I found ourselves standing in a park called Salisbury Garden, on the Kowloon (mainland) side of the city, along the water, surrounded by maybe five or ten thousand protesters.

I saw American flags again, and the old colonial British flag of Hong Kong. I also saw plenty of signs that read “Protect Muslims” — a reference to the Uighurs of Xinjiang, suffering under Chinese government repression.

There was a tense standoff between cops and protesters. Insults were hurled. A girl was arrested. Protesters surged forward and tried to “de-arrest” the girl, and a fight ensued. If you want you can see a video of the fight, taken by the excellent journalist Xinqi Su, who somehow happened to be in all the same places as BB and myself on that day.

Anyway, tear gas started flying, and of course BB and I did what any self-respecting American idiots would do — we ran right toward the tear gas so we could see it up close. At which point a giant wall of gas went up right in front of us, and we both huffed a bit of gas, which finally persuaded us to beat a retreat. After that BB put on his gas mask. The next half hour consisted of police kettling and herding the protesters away from Salisbury Garden along the waterfront in a tightly packed crowd, while both sides hurled taunts at each other.

Shortly after that, as the late afternoon deepened into evening, protesters re-converged in the middle of Nathan Road, the big commercial street that runs right through the middle of Kowloon. Police tried to keep the street clear, but it just wasn’t happening.

That was when I heard the protest song “Glory to Hong Kong” for the first time. If you haven’t heard it, you should watch this video. It’s a nice tune, but the deep and obvious reverence the protesters all had for the song was something I hadn’t ever really seen before.

And that’s when it all came together. I know a national anthem when I hear one. And the feeling I was seeing in the faces of the Hong Kong protesters was patriotism. Not the meme-like faux-patriotism of people who replace their American flag bumper stickers with Confederate ones whenever a Democrat is elected — this was the deep, passionate patriotism of a people united in a struggle for national self-determination.

What I was seeing was an independence movement.

Not officially, of course. The protesters’ five demands included universal suffrage, but said nothing about severing Hong Kong from China. But what I realized, after attending the protests and talking to the protesters, was that Hong Kongers — especially young ones — no longer really see themselves as being of one people with the PRC. Hong Kong has never been an independent country, or even a true democracy — the British, who built the place, initially repressed the locals even more than China has yet done. But Hong Kong has its own history, its own institutions and traditions, its own culture, and even its own language (Cantonese), all of which are mostly distinct from the mainland. Hong Kongers might have dreamed of joining China while languishing under British rule, but now that that has happened, many are deciding that their new overlords are no more native than their old ones; almost no Hong Kongers under the age of 30 identify as Chinese.

But Hong Kong would make a tiny country — only 7.5 million people, smaller than New York City. Against the might of China they have no chance for independence. Thus the flag-waving attempt to appeal to foreign allies — the U.S. or global Islam, anyone who might be able to stand up to their superpower overlord.

No one will. Hong Kong is universally recognized as being legally part of China, the British Empire is a memory, the United States is embroiled in our crippling internal divisions, and global Islam can’t even be bothered to stand up for the Uighurs. The protests have already largely been crushed by a draconian new security law that has taken away most of the autonomy Hong Kong still retained. Protest leaders have been jailed, critics silenced, etc. etc.

So it’s the end of Hong Kong as we know it. But in fact that Hong Kong had already begun to end many years ago, and these protests were in some way a last gasp. Under steady Chinese pressure, Hong Kong’s status as a free-wheeling financial entrepot has long given way to an oligarch-dominated sclerotic economy based on real estate. This has led to a loss of economic opportunity and sky-high rents, which helped fuel the anger of the protesters.

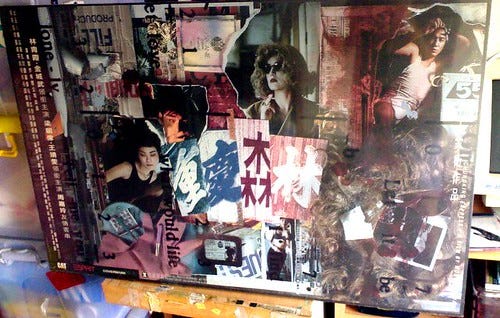

The freewheeling Hong Kong that I had seen hinted at in films like Chungking Express, that had given rise to Stephen Chow’s mo lei tau comedies and Jackie Chan’s zany kung fu and Chow-Yun Fat’s thrilling action movies, is a place you just can’t go anymore. Hence the title of this post. Sure, every city in every era is a place that will never quite exist again; you can’t visit San Francisco in the Summer of Love, or attend a salon in 1700s Paris. But Hong Kong is something else — a nation that never really had a chance to become a nation, a unique and special little civilization being swallowed up by the Manifest Destiny of a vast and implacable empire.

So, where was I? Oh yes, the end of the story.

BB and I had quite a night on Nathan Road, as the protests became increasingly confrontational and the police response more violent. We saw toppled camera poles, Starbucks signs smashed, bricks ripped off the street and hurled at cops and at mainland tour buses. We saw protesters beating a man they said was a “Chinese spy.” We saw a mother with her infant tear-gassed in the street. We tasted tear gas ourselves, two more times. I regretted not buying a gas mask for myself.

Finally we went to see a train station exit that we heard had been firebombed. While we took photos, the police cordoned off the entire area and rushed in and began to rip off people’s masks, search their backpacks, and herd some people into vans. BB and I tried to escape the cordon by saying we were just tourists, but it was a little late for that. Several blocks had been kettled, and there was no escape.

So we ducked into the open lobby of an old apartment building, hoping to hide from the cops. An old security guard opened the grille to let us into the elevator, and BB and I got in along with two protester girls. Together we rode up to the top floor and climbed to the roof, where we watched the police round up the protesters in the sealed-off area we had just escaped.

The girls spoke great English (neither BB nor I speak Cantonese), and we talked to them for a while. They laughed when I asked if they were students; one was a teacher, and the other a fitness instructor. They were struggling middle-class people in service jobs, who like millions of others had risked a lot to come out here and protest.

The police were still sealing off the area we had come from, so in order to escape we’d have to go out the back of the building. The protester girls had a friend who called them and told them there was a way out, so we took the steps down, looking for the exit. That turned out to be the wrong stair, so we climbed back up dozens of floors and found the maintenance stair. This was a crumbling, disintegrating dungeon of a stairwell that looked like it hadn’t been renovated since the 1950s, with tiny little hobbit-doors leading off to who-knows-where. As we descended — the girls going first, tiptoeing to make sure no cops were waiting for us — BB and I looked in one aperture and saw the old security guard, standing by a bank of glowing screens. He gave us a thumbs-up sign as we passed.

“The villagers are helping the rebels!” I whispered to BB. It was all very young-adult-novel.

We made it to the bottom, where we met the girls’ friend. She guided us into an alleyway, and at the end I saw the cops, standing in a line with their backs to us. The girls we had been with bolted in one direction (we never saw them again), while their friend led us in another. On tiptoe we rushed past the cops and into another street that hadn’t been sealed off. BB and I immediately ran out of the protest zone and took an Uber back to our hotel on the island side.

So our little tourist adventure ended, and BB and I flew back to our own divided, declining country, where a few months later we found ourselves joining our own huge protests. And the Hong Kong protesters fought on bravely until COVID-19 came and China seized the opportunity to crack down. The little territory is now being used as a laboratory for authoritarianism, with policies designed by an apparatchik who is an ardent admirer of Nazi philosopher Carl Schmitt. China now reserves the right to arrest Hong Kong activists anywhere in the world, and it’s trying hard not to let Hong Kongers escape to countries like Canada.

Because the real world doesn’t work like a young adult novel, or a 1980s movie, or a video game — the story often ends when the empire strikes back.

But I guess I’ll end this story with a warning to China. Yes, you managed to crush the Hong Kong of the 90s and the 00s out of existence. But that culture lives on in the minds of a generation of Hong Kongers that you’ve insisted on keeping within your borders. And the more you integrate Hong Kong into China, the more pieces of that culture will have a chance to spread. The thing about empires is…they are what they eat.

Good story. Hong Kong's demise is a heartbreaking outcome. There was a time when I would respond, "Hong Kong!" without hesitation when asked what my favorite city was. I last traveled there in the '90s; I think going back now would feel like visiting a grave.

Great one Noah. My wife and I with our two kids have decided to leave our city last month and moved to London. It was devastating to see how Hong Kong, our home, has changed. No one would ever want to leave their home but people did throughout history. Years later when we look back, it would be a lot more clearer than it is now.