Putin is a rest stop on the road of post-Soviet collapse

The narrative of Russian revitalization is more hype than reality.

A popular narrative, popular on both sides of the Atlantic, is that the Soviet Union was a fundamentally weak and ineffectual system, and that Vladimir Putin took over and made Russia great again. This narrative has its roots in both American Cold War propaganda that sought to portray the Soviet communism as hopelessly outmoded, and more recent Russian propaganda that enshrines Putin as a national savior.

The narrative does have some roots in reality. By the time the USSR collapsed, its economy was in a parlous state; the collapse of oil prices, along with macroeconomic mismanagement, had made the country unable to afford food imports. The USSR’s woes were rooted in more long-term weaknesses — unproductive manufacturing that drove the country to gradually become a petrostate, price controls that led to basic shortages, and a closed economy that was unable to effectively import foreign technology or manage its balance of payments. These were all traceable to the ideological weaknesses of Soviet communism, with its emphasis on planning and autarky over markets and trade — mistakes that were repeated across the communist world, until they were correct in almost every country that tried them. These led to the USSR’s eventual economic collapse, despite belated efforts at reform.

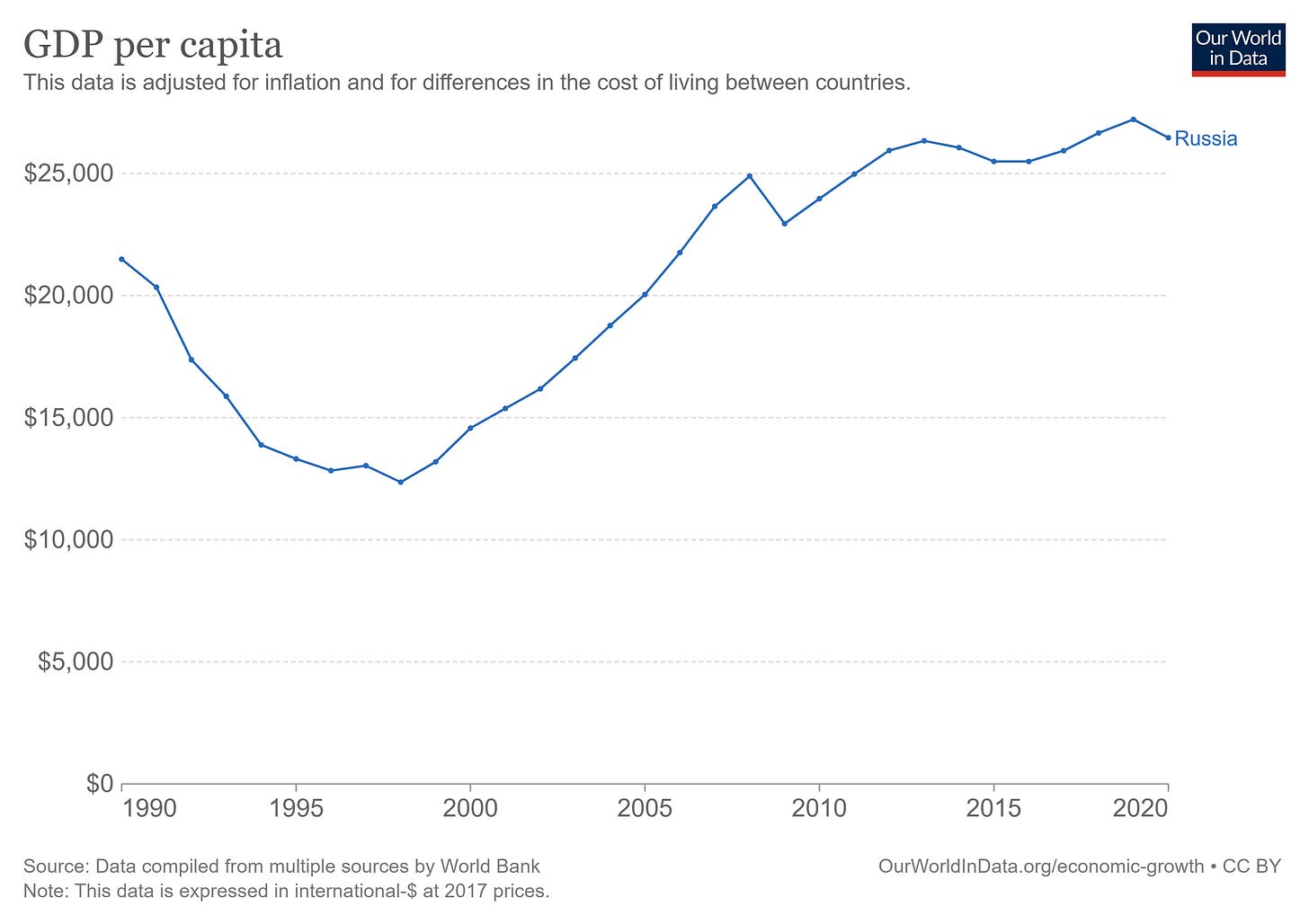

Putin, meanwhile, presided over a pretty dramatic turnaround during the decade of the 2000s. By the time the Great Recession hit, Russia’s per capita GDP had exceeded its pre-collapse levels:

Part of this was because Russia was simply bouncing back from the chaos following the end of the Soviet system. And part of it was due to a massive runup in oil prices from 2003 through 2008:

But Putin’s economic management played a key role as well. Opening up the economy to trade instead of insisting on trying to do everything domestically allowed Russia to specialize in what it was good at doing (i.e. digging up oil and gas), and allowed the central bank to accumulate foreign exchange. The foreign exchange reserves insulated Russia from balance-of-payments crises in several crises — the Great Recession, the post-2014 sanctions, and the 2022 sanctions.

Under Putin, Russia’s society also stabilized from the chaos of the 1990s. There was a 43% decline in alcohol consumption from 2003 through 2019, partly due to Putin’s policies to discourage drinking. The country’s spectacularly high homicide rate fell to fairly low levels:

These factors fueled an increase in Russian life expectancy to higher than Soviet levels (before Covid caused it to fall again):

Russia’s relatively strong economy led to a modest influx of immigrants from other countries of the former Soviet Union, whose economies were mostly weaker. This, combined with a lower death rate, caused Russia’s population — which had fallen in the 90s and 2000s — to grow by about 2 million in the 2010s:

In other words, Putin presided over a real, if modest, revitalization of the Russian economy. And while some of this revival was due to luck, significant parts of it were due to Putin’s leadership and policy acumen.

But look closer at some of these numbers, and it becomes clear that this narrative of Russian revival has been pretty dramatically oversold.

First of all, the increase in population was very small, and it was dependent on a temporary burst of immigration from countries with rapidly shrinking, aging populations. Russia’s fertility rate experienced a minor increase during Putin’s glory days, but never made it to replacement level:

Now, between a fertility drop, the end of immigration and the start of outmigration, the Ukraine war, and Covid, Russia’s population is falling rapidly again. As for social improvements, the decline of alcoholism and homicide is real, but there are some signs that the latter may have been overstated in the official statistics.

Economically, Putin’s miracle stopped in 2008. Oil prices stopped rising, and Russia failed to make any kind of pivot to manufacturing or services to replace the lost revenue. Prudent macroeconomic management may have kept Russia from collapsing in response to the sanctions after 2014, but living standards stopped rising. Russia, which was much richer than Poland, Romania, or the Baltics when the USSR collapsed, now lags these countries significantly. This is quite a reversal of fortunes:

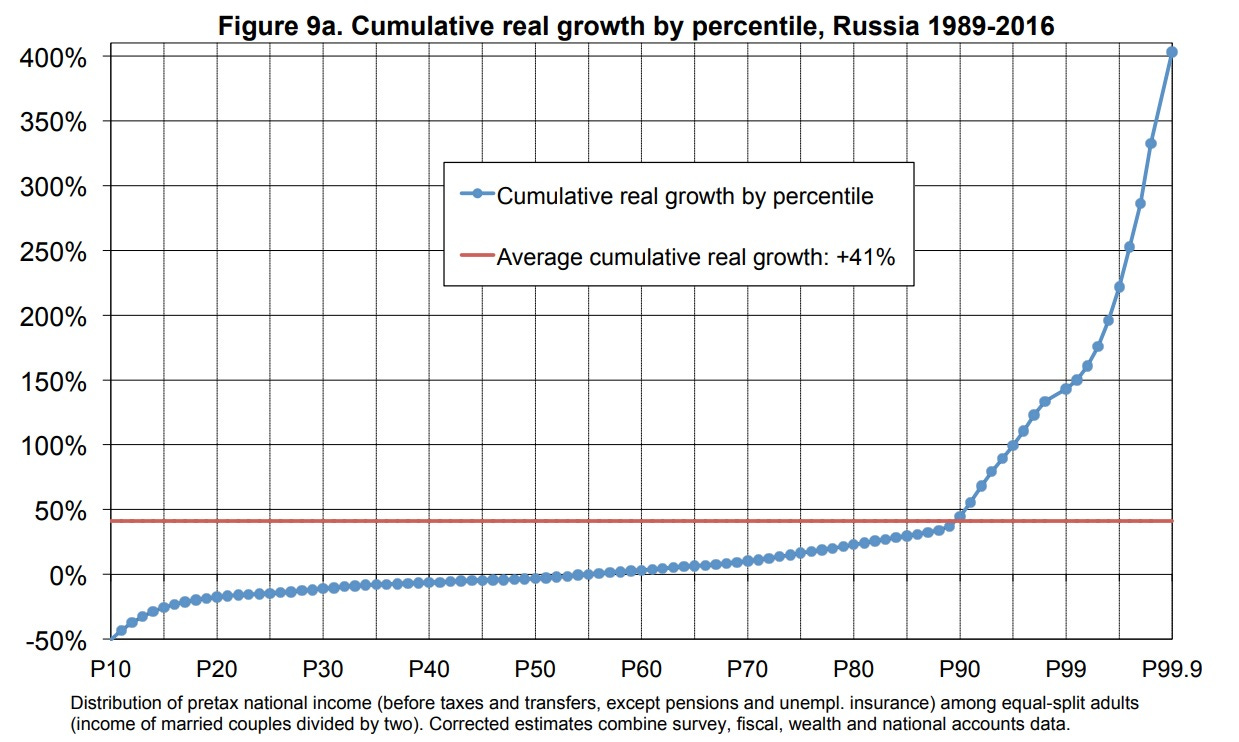

Meanwhile, per capita GDP numbers are averages, so they conceal changes in the distribution of growth. Russian inequality rose massively after the fall of the USSR and didn’t really fall under Putin (until very recently, when rich Russians started getting hit by sanctions). Thus, the median Russian’s income actually declined very slightly between 1989 and 2016, while poor Russians became even more impoverished. Almost all of Russia’s growth under Putin accrued to the top 10% of the country:

This is very different from the 1950s and 1960s under the USSR, when rapid industrialization — even if massively inefficient — managed to raise broad living standards by a considerable degree.

Meanwhile, Putin’s decision to simply follow the logic of comparative advantage — i.e., to let Russia remain a petrostate and rely on imported technology — served the country well in the 2000s but set the country up for long-term stagnation. Oil prices can’t go up forever, and petrostates are notorious for slow long-term growth. Russia’s dependence on Western machinery for oil and gas extraction will also hurt the country even more in the long term, unless Chinese replacements can be arranged.

And embracing trade as a substitute for indigenous technological capabilities left Russia decidedly unprepared for the wars that Putin was determined to fight. Russia’s defense manufacturing relies crucially on imported computer chips, meaning it’s now scrambling to switch from European and American suppliers to Chinese ones. It also relies on Western imports for the machinery it uses to manufacture military hardware, which is one reason tank production isn’t even close to keeping up with its losses in Ukraine.

Putinist Russia’s technological weakness doesn’t just include things the Soviets were bad at, like computer chips and computer-controlled machine tools. It also includes things the Soviets were good at, like space. Russia’s failure to launch more spy satellites leaves it at a distinct disadvantage versus the Ukrainians:

It’s important to remember that Ukraine was also part of the USSR, and was home to a disproportionate share of the old superpower’s advanced manufacturing capabilities, especially in defense. Ukrainian homemade missiles and drones have been wreaking havoc on Russia’s military equipment, even sinking Russia’s flagship.

None of this is to say that the USSR itself was a model of national effectiveness. The communist system was deeply, fundamentally flawed, and by the time the Soviet Union fell it was already degrading from a dysfunctional manufacturing-centric economy into an even more dysfunctional petrostate. But it did manage to hold down inequality, and its stubborn insistence on maintaining some domestic technological capabilities, even at the cost of economic efficiency, gave it a freer hand on the international stage. And it at least kept up the pretense of being a universalist system instead of an ethnic Russian empire built on blood and repression

The age of Putin, in other words, is thus best seen not as the dawn of a new age of Russian power, but as a temporary waystation on the road of Soviet and post-Soviet decline.

But there’s a lesson for the United States and Europe in this story. A country that lets itself be led around by the marginal logic of comparative advantage will end up with short-term economic gains, but these gains may be offset by the loss of deeper technological capabilities. In the 2000s and 2010s it made short-term economic sense for the U.S. and Europe to let China process most of the world’s lithium and cobalt, make all the world’s batteries and consumer electronics, mine all the world’s rare earths, and so on. But just as with Putin’s decision to continue Russia’s transformation into a petrostate, those short-term profits came at a cost. We are just now starting to wake up and realize that cost.

Most of all, Putin and his cronies seem preoccupied with the demographic decline of Russia. Correctly predicting that this is the number one reason for Russia's declining geopolitical fortunes.

Russia's demography is actually worse than the numbers suggest. It is true that Putin has succeeded in keeping the population sort of stable by lowering mortality and welcoming immigrants from post-Soviet nations. But the main problem, low fertility rates, are still there.

These low fertility rates contain a demographic bomb of sorts. The end of the Soviet Union meant a collapse in Russian fertility. The number of births in Russia halved between 1987 and 1993. I know of no other advanced country at peace that has experienced something similar. The bomb here is that the girls born in 1987 are still adding to the birth numbers of Russia while the girls from 1993 are only now entering motherhood in force. Halving the number of potential mothers will of course wreak havoc with birth numbers.

All this is known to Putin and his government. Most probably, demographic considerations have played a part in recent Russian foreign policy. When unable to manufacture new Russians themselves, Russia is simply conquering Russians from neighboring countries that have some to spare.

One crucial element that I think you miss is the impact of outward migration, which saw many of Russia’s best and brightest go to Israel and the US (and even a few to Australia). This has now accelerated again.