Progressives should fear inflation more than recession

Raising interest rates will hurt the economy (and the Democrats) less than the alternative.

In 1919, John Maynard Keynes (pictured above) wrote the following regarding inflation:

As the inflation proceeds and the real value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless; and the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery.

Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.

Some American progressives seem to have forgotten Keynes’ warning. Even as inflation continues to rage, they’re frantically fighting against the idea of hiking interest rates. The reason is that they fear that rate hikes would trigger a recession.

For example, when I suggested on Twitter that the Fed hike rates by 200bps (2%) in a single meeting — instead of the steady pace of 25-50bps per meeting that they’re now promising — a number of progressives were quite alarmed. Arin Dube, an economist at UMass-Amherst, foretold that this would cause “very high unemployment”:

MSNBC anchor Chris Hayes said he believes such a move would throw 5 million Americans out of work. And here’s a thread from the Roosevelt Institute’s J.W. Mason from two months ago arguing that a recession is much worse than inflation (it seems unlikely he has changed his outlook since then). Other progressives in the econ world also play up the threat of recession, even if they don’t explicitly weight it against inflation.

The fear of an economic downturn is certainly legitimate. The Great Depression was the greatest economic calamity in our history so far, and the Great Recession that began in 2008 was enormously damaging as well. The Volcker recessions of the early 1980s that ended the 70s inflation didn’t last as long, but the second one was deep and painful and probably left permanent scars on the Rust Belt. The harms of unemployment are concentrated on society’s most vulnerable.

But at the same time, recession isn’t the only economic danger to worry about. Moderate inflation might be tolerable, but high and accelerating inflation is itself a huge danger to the economy. In the extreme case, it can cause total economic collapse. Even if things never progress to hyperinflation, sustained rapid price rises can hollow out the middle class and lead to all the bad things Keynes warns about in the essay quoted above.

It was Keynes and his intellectual successors who left progressives in the West a precious inheritance — a method for balancing the risks of recession and inflation. If we use monetary and fiscal policy to boost aggregate demand when it’s too low and curb it when it’s too high, we can steer the economy between Scylla and Charybdis. But this requires discipline — we have to be willing to “take away the punch bowl” at some point. What separates Keynesians from macro-leftists (like the MMT people) is their willingness to make that call.

And if now isn’t the time to make that call, then when? Inflation is at its highest in 40 years, and much of this appears to be due to excessive aggregate demand. Recessions are bad, but a mild recession now is far preferable to the severe, Volcker-like recession that will be necessary to quell inflation if expectations become entrenched. And on top of that, inflation is probably a much bigger threat to progressive political priorities than a mild recession would be.

Why inflation is more dangerous than recession right now

First, let’s talk about the possibility that inflation will go away on its own, without the need for rate hikes. Unfortunately, supply-based explanations for the recent inflation, which were always a bit suspect, are now looking unlikely:

Every prediction that inflation would be limited to just a few items, or that it would disappear when the post-pandemic supply shocks faded, has proven wrong. Now, Europe’s situation is probably a bit different — they’re contending with much worse energy and food shocks from the Ukraine war. But in the U.S., there is now every sign that this is a broad-based, persistent, demand-based inflation.

Which means that if we decide to bring down inflation, we need either interest rate hikes or fiscal austerity to bring it down. And interest rate hikes are a much better option. The Fed doesn’t have to take my suggestion of doing 4 months’ worth of rate hikes all at once, but Jason Furman is right that the approach should be “whatever it takes”.

Now let’s talk about the balance of risks. If we raise interest rates, could we get a new Great Depression or the Great Recession? It seems incredibly unlikely. Great Depression-like recessions tend to be caused by financial crises, when the economy has a big private debt burden. Recessions caused by tight monetary policy, in contrast, tend to be short and sharp. Compare the second Volcker recession — or the short recessions of the 50s and 60s — with the Great Recession, or the 90s recession that followed the Savings & Loan crisis.

What’s more, when Volcker caused his big recession, he raised the Federal Funds rate to almost 20%. Whereas even the surprise rate hike I called for on Twitter would raise the rate to less than 3%, and Furman only mentions 6%. Unless the economy has become much more sensitive to monetary policy shocks than it was back in Volcker’s time, the economic danger from such modest rate hikes is…well, modest.

The risk of allowing inflation to run wild, on the other hand, is terrifying. Studies show that economies that enter hyperinflation usually have a period of 2-12 years where inflation is elevated but not “hyper”, after which it explodes. The U.S. has now had substantially elevated inflation for about 1.5 years. So for the Fed to allow this to continue, blandly hoping that the problem will eventually fix itself, could be skating close to the edge of a precipice. If the general public decides that the Fed simply doesn’t care about inflation very much, the result could be a self-fulfilling spiral of rising inflation expectations that ultimately immiserates the whole economy.

But a Great Depression and a hyperinflation are both tail risks. Let’s talk about more likely scenarios.

Suppose that the tradeoff is between letting inflation persist at the current level — around 8-9% — for three years, vs. causing a mild recession in which unemployment rose by 3% and then came down over the same amount of time.

First of all, consider the number of people affected. 5 million people losing their jobs vs. more than 100 million people seeing their real wages fall month after month. Remember, the main reason people hate inflation is that their wages tend to be “sticky” in the upward direction — it’s difficult for wages to keep up with prices when prices are rising quickly and unpredictably. Here is a graph of nominal (dollar) wage growth, courtesy of the Atlanta Fed:

You’ll notice that none of the quartiles are above 8.6%, which is the current rate of CPI inflation. Low-wage workers are getting hit less hard, but everyone is getting hit. (Note: This is different from the first half of 2021, where low-end wages outpaced inflation.) What’s worse, 8.6% is the overall CPI; when you look at the prices of things low-income people tend to spend more of their money on (e.g. gasoline), this decline in real purchasing power is going to look even worse.

And real disposable personal income is now falling as well:

This is why the American people are very very mad about inflation right now. In survey after survey, Americans rate inflation as the #1 problem facing the nation. Here’s Pew:

And here’s FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos:

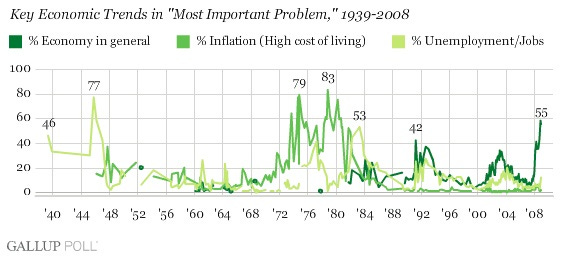

In fact, this fits with the pattern from the 70s and 80s. The number of people naming inflation as the country’s top problem before the second Volcker recession dwarfed the number of people who cited unemployment or the general economy as their top problem during the years of the second Volcker recession:

And this stands to reason, because inflation hurts most people while unemployment only hurts a few. For the vast majority who manage to keep their jobs during recessions, the biggest harm from a weak labor market is that real wages are held down by a pool of unemployed surplus workers. But real wages are going down right now due to inflation!

Now, polls are not a measure of social welfare. Progressives might respond that since a recession hurts the most vulnerable, it’s better to save those vulnerable few, even at the cost of soaking everybody else. That’s a noble sentiment in some sense, but it’s misguided. If the progressive project decides that it’s about soaking the broad middle and working classes to save the jobs of a few, it has forfeited any right to call itself a movement of the masses.

Also, note that it’s a lot easier to offer targeted help to the unemployed during recessions — enhanced and extended unemployment benefits, and various means-tested benefits — than to help the broad middle and working classes during a time of high inflation. There’s simply very little government can do to ease the pain of inflation — it can subsidize consumer goods, but this just drives prices up faster.

In other words, a recession, especially a mild one, is a problem we can deal with much more easily than inflation. Furthermore, it’s a problem that goes away relatively quickly, whereas inflation, if left untreated, can potentially stick around and get worse and worse.

But on top of the asymmetric danger to the economy, inflation also poses a greater danger than recession when it comes to the progressive political project itself.

Inflation puts the progressive political project in danger

Consider the many polls cited above. Inflation is a clear and present threat to the Democratic party right now. If the GOP takes back control of one or both houses of Congress this November, some of it will be due to natural pendulum swings, but inflation will also be a big reason. And if high inflation persists through 2024, Biden’s reelection bid will be in big trouble. Among the potential downsides of inflation is a second Trump term.

Wouldn’t a recession also be bad for the Dems electorally? As far as the midterms go, maybe so (though as we saw in the 70s and 80s, inflation tends to be more hated than unemployment). But if the Fed shocks the economy out of inflation with a mild recession right now, that recession will probably be over by 2024, and Biden’s fortunes will look much brighter.

In fact, there’s a precedent for this. Volcker caused a very severe recession in 1981 that lasted into 1982. But by 1984, it was largely over. And despite the pain of that recession, Reagan was able to win a crushing reelection victory. One of Reagan’s key campaign messages was that inflation was down:

But if the Fed waits until 2023 or 2024 to raise rates enough to crush inflation, Biden could find himself in more of a Carter-like situation. Volcker began his epic rate hikes in the election year of 1980, causing the first Volcker recession in that year. Even though it was a more mild recession than the second one, that small recession, combined with the fact that inflation hadn’t yet come down, might have tanked Carter’s popularity even more than inflation alone.

So in terms of saving the Democrats in 2024, a short, mild recession now is definitely preferable to the same thing — or a more severe recession — two years from now.

But even beyond electoral concerns, persistent inflation presents a grave threat to the entire progressive political project. When inflation is high, it puts political pressure on the government to spend less. Already, that pressure has helped to kill Biden’s Build Back Better bill. And if inflation lasts for two or five or ten more years, it’ll be the same story going forward.

In fact, there’s a good argument to be made that Volcker’s rate hikes saved the progressive project back in the 1980s. As things happened, Reagan ended up cutting taxes but not actually cutting government spending. Had Volcker not brought inflation down, though, Reagan and Congress would have come under enormous pressure to curb fiscal deficits. And there are two ways you can curb fiscal deficits: Raising taxes, and cutting government spending.

Which do you think Reagan would have done? It seems very likely that he would have followed through on his campaign rhetoric and slashed social spending, including entitlements. Because Volcker brought inflation down, however, Reagan felt safe in leaving social spending largely intact.

A future where the Fed fails to quell inflation, therefore, is a future where Democrats have a hard time getting elected and Republicans are empowered to slash spending on health and welfare. Even beyond the immediate harm to American wages, this is an outcome that should worry progressives deeply.

Recessions are scary. But sometimes there are even scarier things out there.

Update: On Twitter, Zachary Carter criticized me for using the Keynes quote that I cited at the top of this post:

Carter notes that Keynes was talking about the postwar hyperinflation that he correctly predicted would arise in Germany as a result of crippling war indemnities. Because Keynes was not talking about interest rate policy, Carter argues, my use of the quote in a post about interest rates is misleading.

But Carter’s criticism sorely misses the mark. The point of my quote was merely to show that Keynes thought inflation was a very bad thing, and that therefore restraining inflation should be one goal of policy. Carter acknowledges this in a later tweet:

The notion of interest rate policy as one of the primary tools for managing aggregate demand (along with fiscal policy), and of the tradeoff between unemployment and inflation represented by demand-shifting policy, came after Keynes; it came from other economists working in the Keynesian tradition. Keynes’ IS-LM model was a key contribution to this idea, but it didn’t get all the way there.

So yes, Keynes thought of inflation as a bad thing, as Carter admits. Keynes also obviously thought of unemployment as a bad thing. Thus, if there is a tradeoff between unemployment and inflation in the present moment, it seems reasonable to think that Keynes would seek a balanced path between the two economic ills. That is all my quote of Keynes was meant to imply, and I think that should have been fairly clear. Perhaps Keynes would have recommended rate hikes as the proper response to persistent inflation, perhaps not; but since interest rates (and fiscal policy) have become our primary tool of demand management, that’s basically what we have to work with right now.

I got into an argument on a popular tech news aggregator about this point, my comment dubbed "...one of the most inane things I've read on HN", and accused of trying to engineer unneeded problems. I guess I really stuck my foot in it, because I think even a month or two ago I think it would have been met with disregard rather than be internet mobbed.

You write:" The Volcker recessions of the early 1980s that ended the 70s inflation didn’t last as long, but the second one was deep and painful and probably left permanent scars on the Rust Belt.". There is no probably about the scars in the Rust Belt. I lived in northeast Ohio until my mid-thirties. The industrial heart of the region was crushed by the Volker Depression. The county which I grew up in, formerly a prosperous manufacturing area, is now a near ghost town with Appalachian levels of opioid addiction. Also, as Brad Delong has pointed out, the long run consequence was the destruction of communities of engineering practice. That is very damaging to the long run performance of the US economy. I agree that inflation is currently too high. However, it doesn't seem to me to be a "hair on fire" emergency.