Progressives need to tell the positive story about immigration

Fortunately, it's true.

One big story in politics this week is a new poll showing that the Hispanic shift toward the Republican party in 2020 might not have been a blip:

Many have been quick to dismiss the poll as an outlier, and the general progressive narrative has been that it’s too early to tell if the shift is real. Sure, fine. But it seems to me that when control of the country is on the line, it’s probably wiser to get out ahead of possible shifts, rather than waiting a decade for the data to confirm that the shift actually happened.

If the Hispanic shift to the GOP turns out to be significant and enduring, progressives will be tempted by plenty of off-the-shelf explanations: “Hispanics are white-adjacent”, “Hispanic men are macho”, “It’s just education polarization”, and so on. All of these explanations have deep empirical shortcomings, in addition to probably being bad messaging. But instead, I want to talk about a big explanation that I think most progressives are missing so far: The stories we tell about immigration.

Three stories about immigration

There have been Hispanic people in America from the start, and some can trace their American roots back quite far, but most Hispanic Americans today are either immigrants, children of immigrants, or grandchildren of immigrants. And so the stories that we tell about immigration have deep and immediate relevance to these folks’ lives and the lives of their families.

What I call the traditional immigrant story goes something like this: Immigrants come to the U.S. to better their lives, escaping religious persecution, stagnant societies, economic destitution, and so on. In America, they start out at a disadvantage due to lack of language skills, connections, and money, and they often face discrimination. But they work hard, learn English, save money, get an education, and fight their way up into the middle class, winning a permanent place for themselves in the tapestry of American society. Then new waves of immigrants come from new countries, and the process repeats, adding to our Nation of Immigrants.

As we all know, this is far from the only story that Americans tell about immigration. Since the birth of the republic there have been restrictionists who seek to cut off the inflow of people from foreign lands. They tell all kinds of scare stories: Immigrants are poor and will sponge off the welfare state, immigrants are dangerous criminals, immigrants will take our jobs and drive down our wages, immigrants are politically subversive, immigrants are culturally alien, immigrants are imported votes for the other political party, and so on. Donald Trump often seemed to be telling exactly this story, and he was successful in making opposition to immigration a pillar of Republican policy. Now, his ideological successors and hangers-on have woven together all of these anti-immigrant narratives into one unified story of a “Great Replacement”, painting immigrants as an invading army intent on dispossessing and displacing the existing population.

But I think what’s less generally realized is how over the last five or six years, progressives have started telling their own dark, negativistic story about immigration. In this telling, immigrants are basically refugees, who come to America out of necessity, because Western imperialism stole the wealth of their homelands and made those lands unlivable. Now, the story goes, people from countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa have no choice but to migrate to the imperial center for survival. This story is best embodied by Suketu Mehta’s 2019 book This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant's Manifesto, which has received fulsome praise from various figures in progressive media. According to the narrative in that book, immigration is not a golden opportunity but a form of reparations — a payment that is owed to the victims of Western imperial depredations.

Additionally, progressive messaging on immigration during the Trump era has focused almost exclusively on the mistreatment of asylum seekers by the Border Patrol and the deportations of the undocumented by ICE. Combining this with Mehta’s story of immigration-as-reparations paints immigrants as a people brutalized twice — once when the West devastated their homelands, and again when they are brutalized in the imperial center.

To say that this dark, negativistic progressive story of immigration is complete bullshit would be going too far. Yes, some countries are sending desperate migrants abroad in part because America destabilized them — especially Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Honduras, the source of the migrant “caravans” that have gotten so much press in recent years. And yes, ICE and CBP often mistreat immigrants, and act with impunity and extra-constitutional license. These abuses deserve negative attention and need to be fixed.

But at the same time, we need to keep some perspective. The migrants detained or turned away at the southern border while they await their asylum hearings represent a very small percent of the total inflow of population in recent decades. Only about a quarter of the immigrant population is unauthorized, and most illegal immigration has historically been for economic opportunity rather than fleeing violence instability. Meanwhile, the countries that send immigrants tend to be on the economic upswing -— research by Michael Clemens has shown that it’s when countries start to climb out of poverty that they start to send people abroad.

In other words, the dark story of immigration that some progressives have been turning to does not describe the experiences of most immigrants, and by extension it does not describe the family histories of most of the children and grandchildren of immigrants.

Instead, the traditional immigrant story — the one about opportunity and upward mobility — is broadly accurate.

The traditional immigrant story is (mostly) right

Most immigrants see their kids move up substantially in the income distribution. A seminal 2020 paper by economist Leah Boustan and Ran Abramitzky tracked literally millions of U.S. immigrants and their children over 200 years, and found the following:

Using millions of father-son pairs spanning more than 100 years of US history, we find that children of immigrants from nearly every sending country have higher rates of upward mobility than children of the US-born. Immigrants’ advantage is similar historically and today despite dramatic shifts in sending countries and US immigration policy. Immigrants achieve this advantage in part by choosing to settle in locations that offer better prospects for their children. These findings are consistent with the “American Dream” view that even poorer immigrants can improve their children’s prospects.

(They focus exclusively on men so that changing gender roles don’t complicate the historical comparison.)

Here is a Bloomberg graph I made of their key finding for immigrant men and their sons between 1997 and 2015:

Notice that in this graph, we’re seeing the performance of sons who were born to immigrants at the 25th percentile of the income distribution. In other words, we’re looking at the sons of borderline-poor immigrant fathers. These are not rich immigrants who come over with money and resources. These are people who start at the bottom.

And despite starting at the bottom, they work their way up. Children of borderline-poor immigrants from every country surveyed except Jamaica end up better off than the children of borderline-poor fathers born in the U.S. This includes Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. (It also includes many children of undocumented immigrants, though as the authors note, we’d expect the kids of the undocumented to show even more upward mobility relative to their parents.)

So the immigrant version of the American Dream is far from dead — instead, it’s the norm. The children of immigrants who come over with very little tend to make it into the middle class. And that includes white and nonwhite immigrants alike.

This is not to say that immigrants and their children and grandchildren face no barriers; indeed, they face plenty. Discrimination is still rife — the U.S. is an unusually welcoming and tolerant country, but bigotry and exclusion are common even in the best of countries. And undocumented status is the biggest barrier of all, inhibiting upward mobility in a vast number of ways. Rather, these obstacles are part and parcel of the traditional immigrant story; the story is that immigrants and their kids and grandkids move up despite all the crap that gets thrown in their way.

And they clearly do.

Hispanics perfectly fit the traditional immigrant story

As the graph above shows, the traditional story of immigrant upward mobility applies in some form to people of every race and from every region of the globe. But Hispanic Americans embody that story more perfectly than any other group in the country today. Most Hispanic immigrants came to the U.S. not as high-skilled workers recruited by companies for technical and professional jobs, but as laborers in the manual labor and service industries. (This has changed in recent years as illegal immigration from Mexico dried up, but was true for a very long time and throughout all of the peak years of the late 80s, 90s, and early 00s.) There are many exceptions, but the typical Hispanic American family story starts at the bottom.

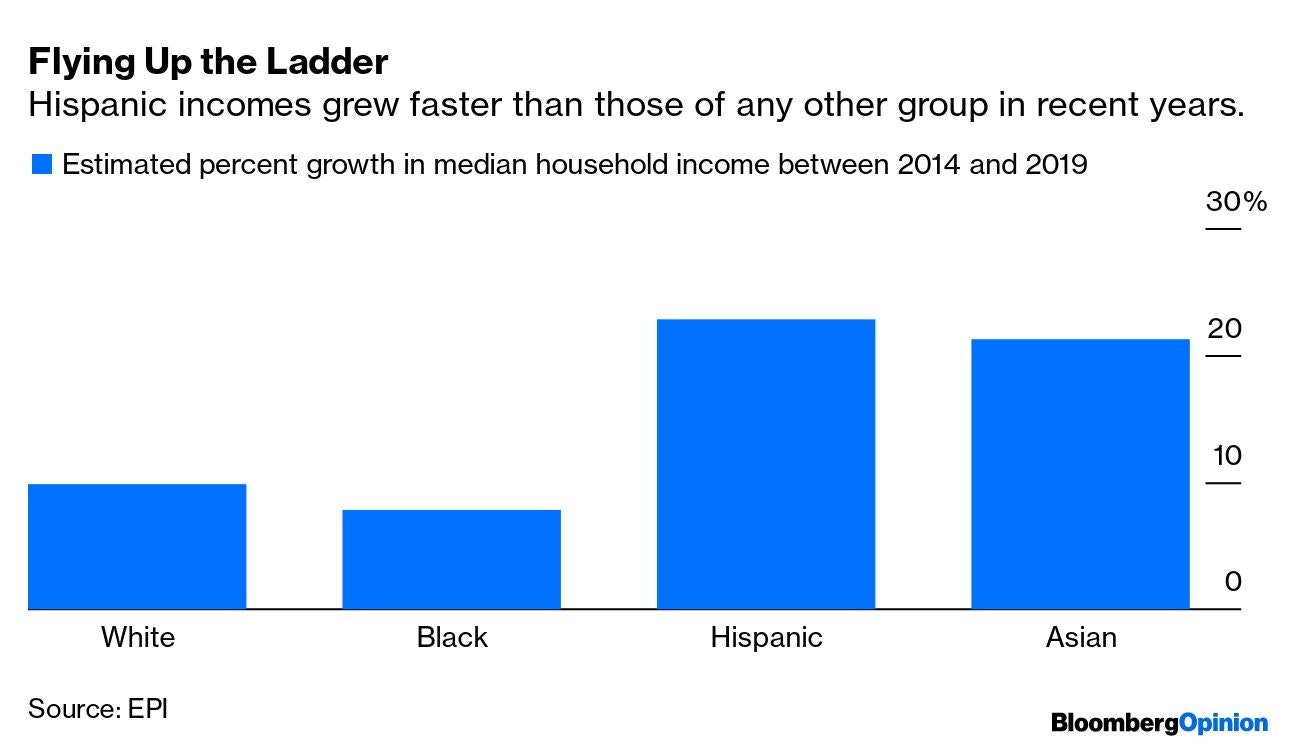

But it doesn’t end at the bottom. The graph above shows the upward mobility of second-generation Hispanic Americans. This upward mobility has continued in recent years; in the boom before Covid, Hispanic incomes grew at a higher percentage rate than any other racial group:

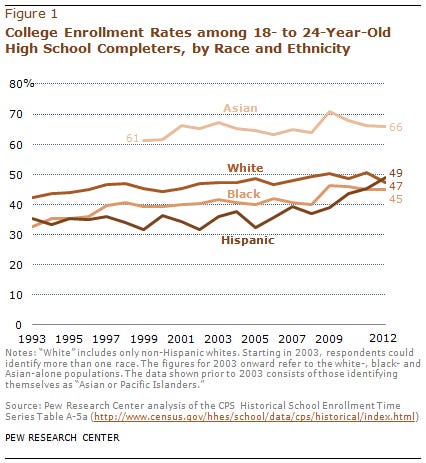

But income is far from the only piece of data to illustrate the Hispanic rise. There’s also education; Hispanic dropout rates have plunged, and college enrollment rates have soared.

Hispanic Americans pretty much all speak English by the second generation, too. You can decry the need for people to learn English in order to prosper, but the simple fact is that it helps an awful lot. And Hispanics are learning English even faster than previous waves of immigrants did.

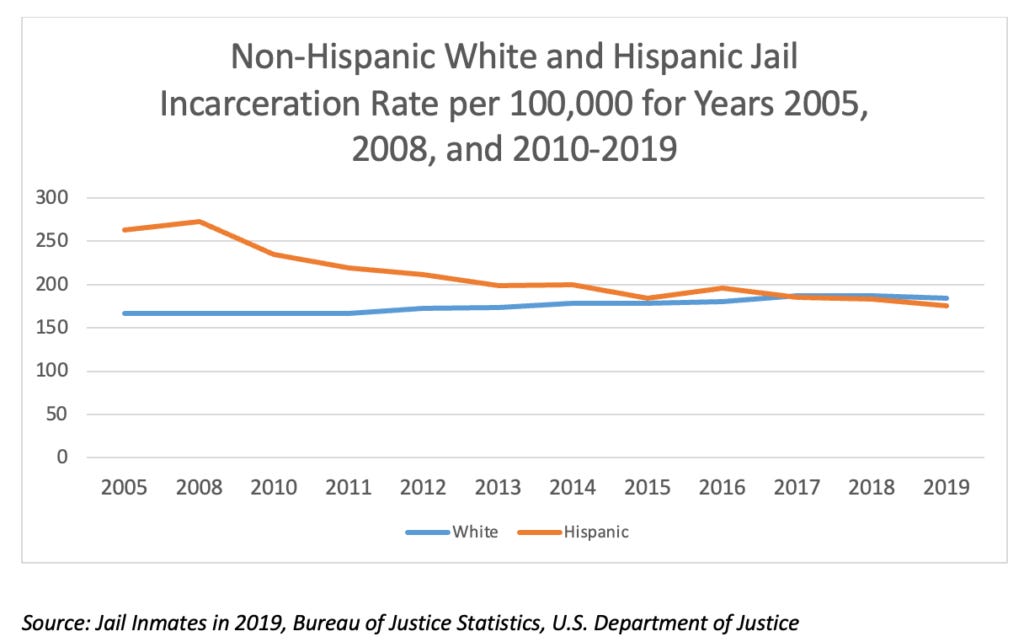

And Hispanic Americans are integrating peacefully into American society, as shown by falling rates of incarceration:

As Keith Humphreys points out, Hispanics going to jail at a lower rate than Whites is pretty amazing in light of the fact that the average age of Hispanics is so much younger than that of Whites (young people tend to commit far more crime than older people).

Now, skeptics will point out that income is not the same as wealth, college enrollment is not college completion, and jail is not prison. On all those metrics, Hispanics have closed some of the gap with non-Hispanic whites, but a gap does remain.

Still, the trends show clear upward progress and bode very well for the future. You have to get income before you can build wealth, you have to enroll in college before you can graduate, and you have to go to jail before you go to prison. So it looks very likely that Hispanics are going to close the remaining gaps in the years ahead. Economists, analyzing income mobility trends, forecast that Hispanics will catch up with non-Hispanic Whites.

And crucially, this progress doesn’t just exist in statistics and economics papers. Hispanics themselves are highly cognizant of their journey into the middle class. Their economic optimism outstrips the national average:

Many polls find that Hispanic Americans are more likely than average to believe in the American Dream than others. This is not to say they don’t expect obstacles or believe in discrimination; many do. But in general, they believe they’ll be able to overcome these.

In other words, the Hispanic immigrant story, broadly characterized, looks an awful lot like the positive traditional story that we tell about past waves of immigrants: Grit, hard work, education, upward mobility, overcoming obstacles and discrimination, and eventually winning parity with more established groups. Yes, it’s a generalization, and it won’t fit everyone’s family story, and we should care about the people whose outcomes are less fortunate than the average. But telling stories is incredibly important in both policy and politics, and this one is as real and accurate as such a generalization can be.

Progressives need to tell this story

Some progressives are certainly still telling this story — especially elected politicians like Biden. But in the age of social media and cable news, progressivism is defined as much by news hosts and NYT writers and university administrators as by senators and governors. We need the thought leaders of this broad progressive movement to turn away from the dark, negativistic story of immigration-as-tragedy, and back to the positive, optimistic traditional story of immigration-as-triumph.

Some progressive activists will resist this story, believing that to trumpet the success of Hispanics will mean blaming Black Americans for persistent gaps in income and other metrics — in other words, the creation of a new Model Minority myth. This is probably why the University of California told its faculty and staff not to say “America is the land of opportunity”. But this makes little sense to me. Is it so crazy to imagine that structural racism in America is primarily directed at Black Americans (and Native Americans), rather than at immigrant groups? Even a casual reading of history suggests that this is the case. There is simply no comparison here, implicit or explicit.

Other progressives may worry that telling a positive story about immigration creates the impression that everything is fine with America, thus sapping popular energy to fight for change. But I see this as wrongheaded. Anger may be a good short-term motivator, but in the long run it turns to despair and encourages passivity. Optimism is necessary for sustained long-term motivation. And a positive story about immigration is exactly the kind of patriotic message that can help progressives draw a contrast with the scare stories that Trump’s movement has been trying to shove down our throats.

Because eventually — perhaps very soon — Republicans will wake up and realize that Hispanic votes are gettable for them. And at that point they will start walking away from the Great Replacement madness and start telling positive stories about the Hispanic immigrant experience, painting themselves as the party that lets people get ahead. This is exactly how Reagan sold the GOP in the 80s, and you had better believe it could happen again. If Democrats are the party that tells Hispanic Americans that they’re a brutalized, permanently excluded minority, and Republicans tell them they’re regular Americans on the road to success, I predict that quite a number of Hispanic voters will choose party that offers them the latter story.

Because the positive story of Immigrant America isn’t just nicer and more pleasant. It also happens to be true.

Progressives don't just choose not to own this positive story, they spit on it.

Republicans embrace it.

Want proof?

When Jamaican-born Winsome Sears Became the first female LT Gov in Virginia, Republicans cheered wildly. Fox News played her victory speech on a loop as she talked about her father coming here with nothing but a desire to work.

As a Republican, grandchild of poor immigrants, it put a lump in my throat and a tear in my eyes. We all fell in love with Winsome despite not knowing her the day before.

How did progressives respond?

"Black White Supremacist win race because Republicans don't want to teach history of slavery in schools. "

Someone made a montage of progressives calling Winsome Sear a white supremacist - it went on and on and on.

Democrats spat on the immigrant made good. It was disgusting.

so i guess i can tell this story. a good friend of mine who is a successfully accomplished scientist with a tenured professorship left his position at a top R1 university on the west coast a few years ago. there were various reasons, but one thing he found personally grating was the tokenism and assumption by his fellow faculty members that he was was the son of hardscrabble economic refugees. at one point a colleague praised the fact that his kids were in a fancy private school and said something that implied the school's openness to diversity must have been a factor.

the issue with that assumption is that my friend has a much better pub record than the colleague, was making 500K a year through salary+consulting, and comes from a very affluent and upper-middle-class family of physicians. he eventually left the elite world of academic science for the private sector because the story academics tell about latinos like him is so monotone and he felt ridiculous wondering always to correct their obvious misimpressions that his doctor father must have come to this country as a farm laborer or dishwasher...