Progressives need to learn to take the W

Outrage is only one motivation for change, and it comes with a cost.

I have gotten some mild pushback for praising the sunny, positive vibes of Kamala Harris’ presidential campaign. Shouldn’t we care about substantive policies rather than empty rhetoric? Well, obviously substantive policy is important, but it doesn’t just materialize out of a vacuum — you need to build popular support for it. And rhetorical attitudes can be very important for doing that.

There are a number of reasons I think the Democrats’ new, more positive vibes will be conducive to better policy, and I plan to write about all of them. But one reason is that I think positivity could fix one of the biggest problems with progressive messaging — the obsession with outrage as the sole motivator for change.

A lot of things in the world are worth getting outraged about (in my opinion). Outrage has been a successful motivating force for many positive changes in the past — civil rights, prison reform, suffrage expansion, and so on. I expect it will be a powerful and important motivator for many positive changes in the future as well. But it’s not the only motivator, and it’s not always the best approach in every situation.

One problem is that outrage often manifests as the search for a bad actor or villain to get mad at. The housing shortage in big U.S. cities is certainly very real. But lots of progressives have approached this problem by blaming developers, “luxury” housing, and corporate landlords. Those actors are not actually to blame for the housing shortage.

Developers are the people who actually build housing — you won’t actually create housing if a developer doesn’t build it. Many developers are nonprofits, and yet have difficulty building homes in California because regulations make construction incredibly expensive. And yet many left-NIMBY types oppose new housing construction on the grounds that it would (supposedly) make profits for developers. Meanwhile, “luxury” housing is a marketing buzzword — any new housing gets called “luxury” because people need to sell it to tenants.

And although concentrated ownership by corporate landlords could indeed become a problem for affordability in the future, corporations currently own far too tiny a sliver of the housing market to be a major factor:

The focus on blaming developers and corporate landlords hasn’t just distracted some progressives from more effective approaches. It has caused some of them to turn their perpetual firehose of outrage against YIMBYs, simply because YIMBYs understand that developers are not the problem. That’s highly counterproductive, since YIMBYs generally have the correct approach to improving housing affordability in America.

As for YIMBYs, they do get mad at NIMBYs who block new housing, but it’s not the core of their theory of change — instead of marching against NIMBYs in the street, YIMBYs work on translating ideas for increased housing supply into helpful legislation, and building broad coalitions of interest groups to support that legislation. So far, it’s bearing some results. Encouragingly, the Harris campaign and the Biden administration — and an increasing number of legislators — seem to be embracing the idea.

But I think there’s another, more subtle cost of perpetual outrage as a theory of change. I think it leads to premature exhaustion and unnecessary disillusionment, by preventing progressives from realizing when they’ve had major successes.

A big example is the War on Poverty. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, poverty was a horrendous problem in America. By the standards of the day, more than one-fifth of Americans lived in poverty in 1962, even after more than a decade of rapid economic progress. That poverty generally meant food insecurity, horrendous housing conditions, and lack of access to basic medical care. It was definitely worth getting outraged about, and many people were outraged.

So progressives did something about the problem. That something was LBJ’s War on Poverty, also known as the Great Society. Its main provisions, rolled out in 1964 and 1965, were Medicare and Medicaid, food stamps, federal education funding, and some job provision programs. The last of these probably didn’t help much, but Medicare, Medicaid, and food stamps became important pillars of America’s welfare state, providing poor people and old people with the basics of food and medical care.

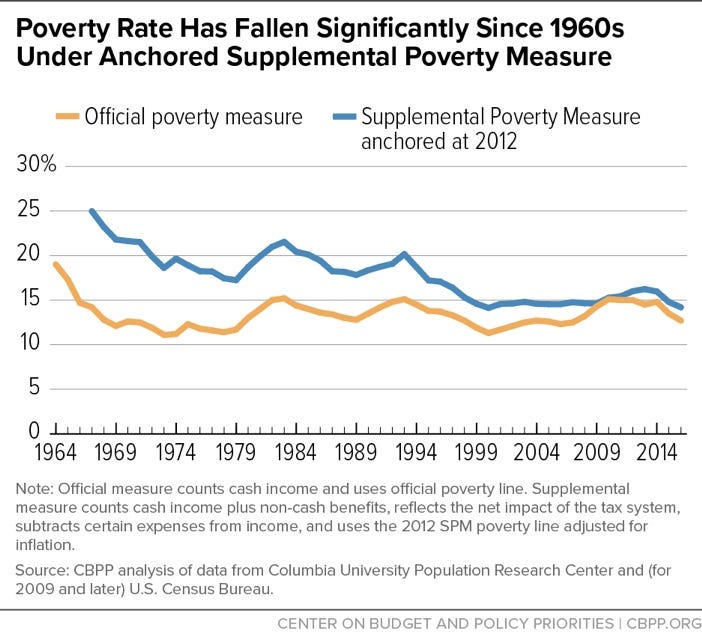

Lots of conservatives will tell you that the Great Society was a failure. They’re wrong. Poverty rates fell by a huge amount in the years after LBJ’s programs were passed. Of course, correlation isn’t causation; the late 60s were a time of rapid economic growth. But the reductions in poverty continued throughout the 1970s, long after growth had stagnated:

But this actually understates the fall in absolute poverty by quite a lot, because it allows for changes in the definition of who’s poor. Burkhauser et al. (2021) have tried very carefully to create consistent measures of absolute poverty rates over time, both in terms of income and consumption. They find that when you hold the definition of poverty constant, the rate fell from about 22% before the Great Society to about 2-3% today:

It’s not hard to see that government programs are behind much of the fall in poverty. When you exclude the impact of those programs, the poverty rate is much higher! Giving poor people food and medical care really does make them less poor — as does giving them housing vouchers and cash subsidies like the EITC. The welfare state does what we created it to do.

And yet it’s not just conservatives who fail to appreciate the staggering magnitude of this success. Progressives like Matthew Desmond regularly claim that poverty in America is intractable:

In the past 50 years, scientists have mapped the entire human genome and eradicated smallpox….infant-mortality rates and deaths from heart disease have fallen by roughly 70 percent, and the average American has gained almost a decade of life…The internet was invented…On the problem of poverty, though, there has been no real improvement — just a long stasis. As estimated by the federal government’s poverty line, 12.6 percent of the U.S. population was poor in 1970; two decades later, it was 13.5 percent; in 2010, it was 15.1 percent; and in 2019, it was 10.5 percent.

Desmond’s belief that poverty hasn’t fallen relies on the official poverty measure, which updates its definition of “poor” over time, so that more and more income/consumption is required in order to be defined as “not poor”. On one hand, it’s fine to have measures like this — as our country gets richer, our floor for what constitutes a minimum acceptable standard of living should rise. But if we want to measure the impact of welfare programs like food stamps, Medicaid, and the EITC, we can’t just update our standards in order to cancel out the effect of these programs, and then conclude that America hasn’t done anything to reduce poverty!

Nor is Desmond the only progressive who claims that poverty in America hasn’t fallen — progressive influencers like Robert Reich regularly repeat this claim. Part of this might simply be unfamiliarity with how poverty is defined, and failure to think carefully about how to measure the impact of antipoverty programs. But there have been plenty of wonky articles written debunking the talking point, and yet it persists.

My hypothesis is that some progressives don’t want to acknowledge the success of the War on Poverty — and of subsequent welfare programs like the EITC and Child Tax Credit — because they’re afraid that acknowledging past successes might reduce outrage, and thus reduce momentum for further reform.

We encountered this quite a lot in the 2010s, regarding the issue of racism in America. It’s blindingly obvious that America is much less racist than in the 1960s — whether using the common definition of racism as bigotry and discrimination, or more academic notions of “structural” racism measured by disparities in outcomes. But in the 2010s, if you pointed this out, enraged progressives would excoriate you with some version of “So you think everything is fine, and that racism has been solved?”. Acknowledging real progress was seen as an attempt to defuse popular pressure for change.

Simply put, many progressives seem not to know how to acknowledge their own victories — in the parlance of our times, they refuse to “take the W”. They’re so dependent on outrage as their motivating force that they recoil against any positivity that might sap that wellspring of anger.

This ends up hurting progressive causes, for a number of reasons. Most obviously, it leads progressives to incorrect conclusions about which tools are effective for achieving their goals. If you insist on telling yourself — and the world — that poverty in America hasn’t fallen, you’ll discount the power of the welfare state. That will also play into conservative hands, since the idea that welfare programs are ineffective is central to the arguments against them.

Another reason progressives shouldn’t rely exclusively on outrage is that it’s probably a lot more powerful in the short term than in the long term. Organizational behavior researchers and management experts will generally tell you that flagellating your employees can motivate them to greater efforts for a while, but will eventually lead to burnout and cognitive exhaustion. Theories of long-term motivation, like the broaden-and-build theory and self-determination theory, emphasize harnessing positive emotions of hopefulness and growth.

It’s reasonable to think that activism, politics, and social change work much the same. Outrage will get people into the street, or motivate a boycott or a pressure campaign or a backlash election. And that will often provoke a fairly immediate policy response. But over time, staying outraged all the time probably leads to general burnout and exhaustion.

You can see this happening in the 2020s, after years of sustained outrage — activists are finding themselves unable to sustain their energy. Protests against abortion bans have been fairly anemic. And it’s not hard to see why — rates of depression among young progressives have soared. There’s a fair amount of research suggesting that political negativity is being “internalized” — for example, this is from Gimbrone et al. (2022):

We hypothesize that increasing exposure to politicized events has contributed to these trends in adolescent internalizing symptoms, and that effects may be differential by political beliefs…Depressive affect (DA) scores increased for all adolescents after 2010, but increases were most pronounced for female liberal adolescents…It is therefore possible that the ideological lenses through which adolescents view the political climate differentially affect their mental wellbeing.

After decades of progress against poverty, racism, and sexism, the progressive culture of the 2010s told young Americans that everything in their country was horrible and that they needed to revolt against it. They obliged, pouring into the streets in anger and provoking a bit of real change. But in the end, the momentum ran out, because sustaining constant negative emotions is a form of self-punishment, and self-punishment incurs heavy long-term costs.

On top of that, outrage eventually reduces the desire for social change among the broader non-activist public. Plenty of surveys show that Americans are exhausted with politics, and are now actively tuning politics out. That’s obviously due to both progressive and conservative outrage. But basically, if you want the nation to be able to actually care about anything at all in the political sphere, you should realize that years of nonstop shouting comes with a price.

Again, this is not to say that outrage is never appropriate, or that it’s never effective. Sometimes it is. But it’s suboptimal to have it be the one and only motivating force behind all pressure for social change. You need positive motivations too — hope, including rational hope based on past successes, is important.

That’s why I’m happy that the Harris campaign has embraced “joy” as its motif. Some progressives are inevitably unhappy with this, but a surprisingly large number are embracing it. After so many years of being told to think that the world is going to hell in a handbasket, the chance to actually feel good about the nation and the world must feel like a breath of fresh air. America has come a long way, and it’s really a pretty great place despite its problems, and sometimes you just need to take the W.

I agree. I never got over progressives' downplaying of the significance of the ACA (Obamacare). The pre-existing conditions protections are enormously popular and had a profound impact on millions of Americans who were previously denied health coverage.

There were a lot of problems with the implementations of healthcare exchanges, and it did raise prices for certain people who were able to buy health insurance before its implementation. But it nearly HALVED the uninsured rate -- it went from over 17% to around 10%.

People like me, who had pre-existing conditions, COULD NOT buy health insurance before the ACA except through an employer, and there were few regulations on what employer plans had to cover. I grew up with parents who didn't have steady jobs with benefits and they were constantly struggling to pay for my insulin and test strips (type 1 diabetic) and trying (and failing) to get us on Medicaid. Without the ACA, I probably would have had to get a full time job at 18 to get insurance. I don't know if I would have been able to go to college. I can hardly overstate the impact this legislation has had on my life.

So why didn't progressives scream it from the rooftops that the ACA was a huge win for American access to healthcare?!? Why did they let Republicans label it Obamacare and successfully pretend it was a bad thing for YEARS?!? I have a feeling it's because they thoughr that acknowledging this landmark legislation might have cooled people's enthusiasm for Medicare for all or other, even more progressive, healthcare legislation. I doubt it, though. As you said, they should take the W.

An illustration I like of the progress we have made in terms of absolute poverty (if not relative poverty) is from the National Health Examination Survey of the early 1960s, called Total Loss of Teeth in Adults, which estimated that HALF of all adults over 65 had lost ALL their permanent teeth from both their jaws (in c. 1960). Today, the CDC says it is about 10%.