Pinochet's economic policy is vastly overrated

Mining a bunch of copper, helping your cronies get rich, and pumping up land prices is not a "miracle".

Chileans just rejected a new draft constitution at the polls. The draft constitution had been offered in response to massive nationwide protests in 2019, which began over bread-and-butter economic issues but evolved into a wider movement to fully reject the legacy of the dictator Augusto Pinochet, under whose rule the current constitution was written in 1980. I assume the reformers will get to work on a new draft.

In the U.S., Pinochet is often a talking point in economics debates. He was a brutal dictator, who killed thousands and who tortured, imprisoned, and/or exiled tens of thousands more. It’s very understandable that Chileans would want to expunge any portion of his legacy. But in the U.S., it’s his economic policy that continues to be debated decades later. Some libertarians believe that despite the brutality of his regime, he implemented economic policies that were wildly successful in raising Chilean living standards.

Milton Friedman, a leading economist and libertarian thinker of the time, referred to this as the “Miracle of Chile”. In fact, Pinochet was advised by a group of Chilean economists known as the “Chicago Boys”, a number of whom studied under Friedman at the University of Chicago. For decades later, and even to this day, a number of folks on the political right believe in this miracle. For example, here’s what Bret Stephens wrote for the Wall Street Journal in 2010 in an article entitled “How Milton Friedman saved Chile”:

In 1973, the year the proto-Chavista government of Salvador Allende was overthrown by General Augusto Pinochet, Chile was an economic shambles. Inflation topped out at an annual rate of 1,000 percent, foreign-currency reserves were totally depleted, and per capita GDP was roughly that of Peru and well below Argentina’s…Pinochet appointed a succession of Chicago boys to senior economic posts. By 1990, the year he ceded power, per capita GDP had risen by 40 percent (in 2005 dollars) even as Peru and Argentina stagnated.

And here’s Axel Kaiser writing for the Cato Institute in 2020:

Following the failed Marxist experiment of Chilean President Salvador Allende, a free‐market revolution led by the so‐called Chicago Boys in the 1970s and 1980s created the conditions necessary for the country to experience an “economic miracle” that captured worldwide attention.1 As Nobel laureate economist Gary Becker (1997) put it, Chile became “an economic role model for the whole underdeveloped world.”

Even Paul Krugman called Pinochet’s reforms “highly successful”, in his 2008 book.

For many, Pinochet has thus been slotted into a familiar archetype — the authoritarian modernizer, who represses his people but boosts their material standards of living. Debates over the legacy of authoritarian modernizers, whether on the right or the left, typically fall into a politics-vs.-economics frame, arguing whether making the “omelette” of material prosperity requires “breaking a few eggs” of human rights.

But when it comes to Pinochet, I feel like the premises of this debate are flawed. Because Pinochet’s economic legacy is not really an economic miracle at all.

Pinochet’s growth record

First, let’s look at how much Chileans’ economic situation actually improved under Pinochet. He was in power from 1973 until 1990. During that time, Chile’s living standards rose by just 30% — an annualized growth rate of just 1.5%. That would be considered slow growth for a rich country in 2022; for a poor country in the 1980s, it’s just abysmal. In fact, over the years of Pinochet’s rule, Chilean living standards actually fell behind American living standards, even though this was a period of unusually slow growth for the U.S.:

As a developing country, you’re not supposed to fall behind developed countries; you’re supposed to catch up! Poorer countries are supposed to grow faster than rich ones. And Pinochet’s Chile fell behind the U.S. even as it was far poorer in absolute terms:

It’s true, as Bret Stephens points out, that Chile did do better than Argentina and Peru during this time. But those countries were also badly mismanaged, and were getting steadily poorer. When we look at Chile’s growth performance in the Pinochet years relative to its Latin American peers, we see that although it eventually breaks out of the worst-performing group in the late 80s, it was pretty middle-of-the-pack even so:

Now, Pinochet’s record does suffer from a deep depression in the first full year of his rule. You can argue that this was not his fault, and was due to the mess he inherited from the predecessors that he overthrew. But the worst year of that depression, by far, was 1974, so it’s quite possible Pinochet mismanaged this transition (more on this in a bit).

And it’s impossible to blame Pinochet’s predecessors for the even bigger crash in 1982-3, which led to a fall in Chilean living standards of 15%. For reference, U.S. living standards in the Great Recession of 2008-9 fell by around 5%. So a big part of Chile’s slow growth during the Pinochet years is attributable to the economic calamity of the early 80s.

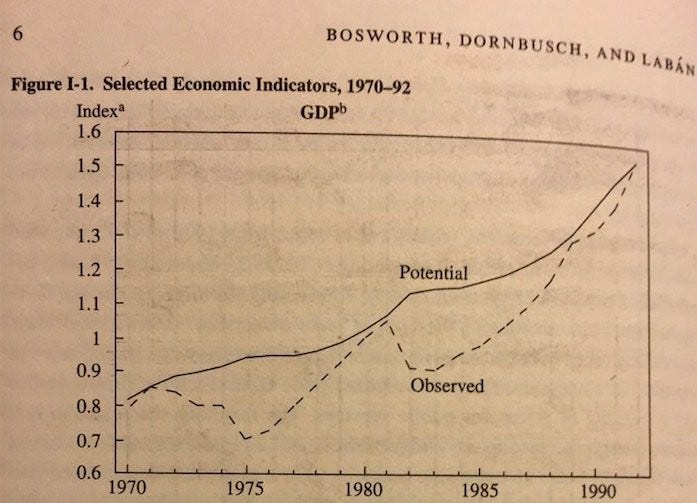

Update: A friends me this excellent 2020 paper by Edwar Escalante that compares Chile’s performance under Pinochet to a synthetic control — i.e., a weighted average of other countries that started out the period with similar characteristics. The upshot:

[R]elative to the control, Chilean income per capita greatly underperformed for at least the first fifteen years after Pinochet’s coup…The evidence suggests that Chile’s remarkable economic growth during the period 1985–1997 did not depend on Pinochet’s autocracy.

And here’s the key graph:

Anyway, that’s the macro story. What about the specific policies that led to this underwhelming outcome?

Pinochet’s big mistakes

The legend of Pinochet actually begins with the legend of Salvador Allende, the democratically elected president that Pinochet overthrew. In the U.S., Allende is best remembered for trying to create a computer system to manage the economy, with a fancy Star Trek style control room (in fact, the system’s primary use was to break a trucker strike). But in fact, Allende mismanaged Chile’s economy, in ways very similar to what Hugo Chavez did in Venezuela. He nationalized much of the country’s industry and ran huge budget deficits (as much as 30% of GDP, double the U.S. deficit in 2020). As oil is to Venezuela, so copper was to Chile — Allende was subsidizing his vast social projects and inefficient state-owned enterprises with copper earnings, and when the global copper price crashed, it took Allende’s whole economic model with it. After three years of this, the economy was experiencing inflation as high as 1000%, and Allende’s attempts to control it with price controls predictably led to widespread shortages and even worse inflation. Wages crashed, living standards fell by 10%, and massive strikes and protests naturally ensued. (Some leftists, predictably, blame this economic disaster on the U.S., but they are wrong.)

When Pinochet overthrew Allende in late 1973 (with a bit of help from the CIA), he succeeded in getting inflation under control through a brutal austerity program. When hyperinflation takes off, you need both fiscal and monetary austerity in order to stop it, and these are always painful. Some economic historians believe that this necessary austerity was the reason that living standards fell by another crushing 13% in 1974.

But it’s worth noting that both Argentina and Israel beat their hyperinflations in the 80s and early 90s without suffering big drops in living standards — indeed, hyperinflation itself was so terrible for the economy that ending it was enough to generate a recovery, even with the punishing austerity. So it seems likely that the economic disaster of 1974 was at least exacerbated by other factors. The political chaos created by Pinochet’s coup is one possible additional factor. Another is the chaos of Pinochet’s initial rapid privatization program. In 1974, Pinochet reversed some of Allende’s nationalizations, often in a corrupt way that rewarded political cronies. Here’s a timeline of privatizations from a 2020 paper by Gonzalez et al., which also has data on the corruption involved:

“Shock therapy” didn’t go well in East Europe, so there’s reason to suspect that Pinochet’s similar program in 1974 caused a similar temporary crash in living standards.

So that may have been Pinochet’s first big mistake. The second was bad macroeconomic and financial policy. The economics blogger Pseudoerasmus writes:

Pinochet also liberalised the capital account, letting in ‘hot money’ capital flows, much of which went into a real estate bubble in the late 1970s. Because of this, Chile faced the debt crisis in the early 1980s just as much as any other Latin American country…The financial austerity in the face of the debt crisis erased the economic recovery of 1973–82. This was purely Pinochet’s mismanagement and incompetence.

Meanwhile, Tyler Cowen writes:

The early to mid 1980s were a disaster, largely because Chilean banks were unsound and Chile pegged to a rising U.S. dollar. This was the biggest economic mistake of the Pinochet regime. It was a huge error which ruined the Chilean economy for years.

Liberalization of a developing country’s capital account — i.e., allowing foreigners to invest a ton of money in your country but also to yank it whenever they want — is a famously risky move. Foreign capital is extremely fickle and volatile, and when it withdraws suddenly, a country typically gets plunged into a classic emerging-market debt crisis. In fact, you can see from the growth graph above that a lot of Latin American countries had debt crises in the early 1980s, though Chile’s was more severe. This is from the IMF in 2001:

In 1978, Chile began to amass a large external debt to foreign commercial banks…Reflecting the privatization of state enterprises and a speculative boom fueled by the liberalization of domestic markets, most of this debt was owed by the private sector…From end-1978 to end-1981, the external debt of the private sector more than doubled, from $5.9 billion to $12.6 billion…

[T]he current account deficit widened further, but the authorities treated it with what they thought was benign neglect…a growing portion of the financing of the deficit was not conducted at “arm’s length,” owing to the close ownership and management linkages between banks and enterprises[.]

In other words, the Pinochet regime encouraged its cronies to borrow too much money, and looked the other way as they built up a huge stock of bad debt. When an economic shock hit (commodity price declines, as usual), the house of cards collapsed, and the Chilean people were left to suffer the consequences. Of course, as Cowen points out — and as is so common in these emerging-market crises — Pinochet’s peg to the dollar made the adjustment more abrupt and painful than it had to be.

In other words, the crash of the early 80s — which left Chile poorer in 1983 than when Pinochet seized power in 1973 — can be laid squarely at the feet of Pinochet’s poor macroeconomic management and cronyist finance.

Pinochet’s structural transformation was underwhelming

In addition to causing one or possibly two massive economic depressions, Pinochet failed to transform the structure of Chile’s economy during his years in office. Pseudoerasmus writes:

Almost all of the economic growth in the Pinochet years was simply recovery from recession, i.e., closing the output gaps that he himself created. There was no change in trend output growth, which is sort of what we expect from ‘miracles’ in economic development.

Tyler Cowen asserts that Pinochet managed to diversify the economy:

Chile moved from very high tariffs to virtual free trade. The Chilean economy diversified and became far less dependent on copper; this included some moves to hi-tech and light industry. The regime gets high marks on this score, as few modern nations have benefited more from free trade.

But I’m distinctly underwhelmed here. Usually, economic miracles — such as the one under Korean dictator Park Chung Hee — are accompanied by industrialization. Under Pinochet, however, we see deindustrialization:

Note that this deindustrialization continued after Pinochet was out of office, as we’ll discuss in a bit.

So if free trade didn’t diversify Chile’s economy into industry, what did it diversify into? Services:

Note the massive decrease in service industries in 1974; I suspect this was due to Pinochet’s hasty privatizations. Also note the huge spike in service industries in 1982 — this was due to the real estate and banking boom, just as Pseudoerasmus and the IMF pointed out.

That is not a healthy sort of diversification. In fact, mineral rents as a share of GDP bounced right back after the real estate boom was over:

I don’t see any diversification or structural transformation in these graphs.

In terms of social policies, Cowen notes that Pinochet’s privatized social security system is “no longer a system to be envied”, and that he increased welfare spending but in ways that were “generally inegalitarian”.

So in addition to causing one or two huge economic disasters during his term, Pinochet encouraged financialization and deindustrialization, and failed to accelerate Chile’s trend rate of growth. This record is less bad than Allende’s, but it’s far from what I’d call good, and it’s certainly nothing that anyone should call an economic “miracle”.

Does Pinochet get any credit for the boom after he was gone?

The one final argument in favor of Pinochet is that although his policies didn’t accelerate growth while he was in power, they paved the way for fast growth after he was gone. Cowen writes:

Much of the superior economic performance of Chile came after Pinochet left the stage…But the roots of this growth spring from the Pinochet years. The moderate and left-wing successors left virtually all of his economic policies in place and of course they were democratic and eliminated the torture.

And Pseudoerasmus writes:

Pinochet’s structural reforms largely survived his rule — albeit with more redistribution under democratic governments, more ‘light’ industrial policy, as well as capital account controls, which were actually implemented by Pinochet after 1982. Clearly, Chile is much closer to the neoliberal paradigm, albeit with anomalies, than Chile was in 1969 or 1973.

Stephens and Kaiser make variants of this argument as well.

In fact, Chile did see a long economic boom after Pinochet was removed from power in 1990. It started outgrowing both the U.S. and its South American peers:

Except for Panama and a couple of tiny countries, Chile is now the richest country in Latin America, with a GDP per capita similar to Bulgaria.

But looking under the surface, we see that Chile has steadily deindustrialized, with manufacturing falling from about 18% of GDP when Pinochet was overthrown to about 9% today. When we look at what Chile exports, it’s still mostly copper with a few other natural resources:

This dependence on a single commodity for export revenue leaves Chile exposed to the price of copper. In fact, it was a drop in the global copper price that caused Chile’s economic growth to flatline in 2013:

(I suspect that this sudden flatlining of what had been two decades of steady growth contributed to the unrest in 2019.)

It’s possible for commodity exporters to get rich — look at Norway, Australia, and Saudi Arabia. But you’re inherently limited by the ratio of resource endowments to population, and vulnerable to commodity price swings. Chile has undoubtedly managed its economy well since 1990, but a well-managed copper mine is still just a copper mine. Unlike authoritarian modernizers in Asia, Pinochet did nothing to switch Chile toward an industrial model that could propel it into the ranks of the developed countries.

Now, maybe there was nothing Pinochet or any of his successors could do about that; structural transformations are really hard! The vast, impersonal forces of economic agglomeration are difficult to overcome, and no one else in Latin America has been able to become a manufacturing-based economy either. But at the same time, there’s not much that’s miraculous here.

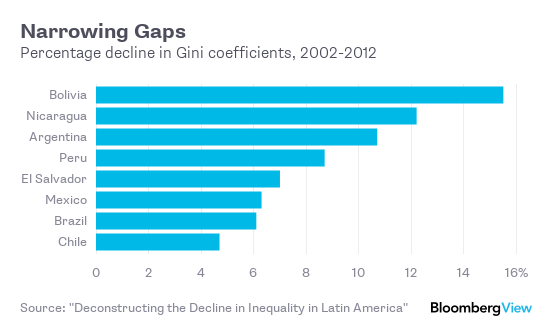

And Chile’s GDP outperformance has also come at a cost — high inequality. Pseudoerasmus points this out:

Uruguay, despite having a lower GDP per capita , has a higher mean income than Chile at every quintile of the income distribution, except the top. I suspect something similar prevails for Argentina.

In recent decades, Latin American countries have generally lowered their sky-high inequality levels. But Chile’s drop in inequality has been more modest than most:

Thus, even if we credit Pinochet with the performance of his successors (and of course that’s a big “if”), the result is decent but not what I would call miraculous.

So to sum up, the standard story of Pinochet — that he was a brutal authoritarian modernizer whose free-market policies produced an economic miracle — just doesn’t hold up at all. He was brutal enough, but his economic policies were not very transformational. He arrested the slide into hyperinflation under Allende, which is to his credit. But his own rule produced repeated economic disasters and failed to transform the economy or accelerate trend growth.

So libertarians should just stop using Pinochet as an example of how free-market policies produce economic magic. The irony here is that there’s a much better example available. There was a dictator in recent history who slaughtered thousands of his own people, but who liberalized his country’s economy, privatizing state-owned enterprises, dropping price controls, and opening up to trade, and whose country did experience a miraculous and sustained economic boom as a result. Heck, he even took economic advice from Milton Friedman.

His name was Deng Xiaoping.

Note that Peru had a somewhat similar growth path after shock therapy and liberalization: moderate growth under Fujimori and faster growth after he left. As much as I despise Pinochet, I think your article may underestimate the long term impact of structural reforms, even if it's likely true that the democratic environment that followed his government was more favorable for growth. One important fact is that Peru's and Chile's new and much more free-market oriented constitutions remained even after they left, and this helped prevent macroeconomic policy mismanagement. Peru's constitution explicitly forbids the government borrowing from the central bank, for example.

I agree that Chile (and Peru) still rely too much on commodities and are not precisely industralized economies. However, they are macroeconomically much more sound that most latin american economies.

Zambia was a copper based economy too. Still probably is but became an highly indebted poor country needing debt forgiveness. Pinochet was a monster whereas Zambian Presidents were, most of them, just corrupt. But it may be worth comparing them to see whst the commodity curse did to Zambia. However not so many available resources, comment or research exists for Zambia.