Pakistan’s economy appears to be in pretty bad shape. Atif Mian, a Princeton economist who immigrated from Pakistan, recently wrote a long and dire thread about the problems facing his native country:

My first reaction after reading about Pakistan’s situation is that it looks like it’s headed for a crisis similar to the one that recently befell Sri Lanka. I wrote a long post about Sri Lanka the other day, using it to explain the features of the classic “emerging-markets crisis”:

Many of the particular root causes of Pakistan’s situation are different than in Sri Lanka — they didn’t ban synthetic fertilizer or engage in sweeping tax cuts. The political situations of the two countries, though both dysfunctional, are also different (here is a primer on Pakistan’s troubles). But there are enough similarities at the macroeconomic level that I think it’s worth comparing and contrasting the two.

In my post about Sri Lanka, I made a checklist of eight features that made that country’s crisis so “textbook”:

An import-dependent country

A persistent trade deficit

A pegged exchange rate

Lots of foreign-currency borrowing

Capital flight

An exchange rate crash (balance-of-payments crisis)

A sovereign default

Accelerating inflation

So let’s go through each one of these and see how it applies to Pakistan.

1. Import dependence ✔️

Remember, the root cause of an emerging-market crisis is import dependence. This means that a country imports much of the basic goods that it needs in order to live — especially food and fuel. Mian points out that Pakistan is pretty dependent on imports:

Fuel is the biggie here — more than a quarter of Pakistan’s total import bill goes to pay for fuel. In recent years it has become a lot more dependent on imports of liquified natural gas.

Food doesn’t look to be as big of a problem — Pakistan imports a fair amount of food, but it also exports a fair amount. That said, Pakistan’s population is pretty poor and malnourished, so even small disruptions to food imports could cause a lot of suffering there. And a cutoff of fuel imports would probably disrupt local agriculture quite a bit, which could cause output to crash and force Pakistanis to rely on imported food that they suddenly couldn’t afford.

In other words, if Pakistan’s currency (the Pakistani rupee) crashes in value and it suddenly can’t afford imports, its economy is in big trouble.

2. A persistent trade deficit ✔️

Remember that the reason a currency crash represents a crisis for an import-dependent country is that when the currency crashes, it’s a lot harder for a country to buy the foreign currency (“foreign exchange”) that it needs to buy imports.

There’s another way to get foreign exchange — by exporting. When you export, you get paid in foreign currency. But if a country runs a large and persistent trade deficit, then it doesn’t have a cushion to fall back on.

So that’s bad news for Pakistan. It means that when the Pakistani rupee crashes, it will have to borrow to get foreign exchange — at a time when borrowing will suddenly have gotten a lot more expensive.

3. A pegged exchange rate ❌

This is one big difference between Sri Lanka and Pakistan. And it’s good for Pakistan! Sri Lanka pegged the Sri Lankan rupee to the U.S. dollar, so that when the currency crisis came, it came all at once, when the peg was broken. But Pakistan lets the Pakistani rupee float freely. That means that we’re less likely to see sudden, catastrophic downward moves.

That doesn’t mean Pakistan is safe from a currency crisis. What it means, though, is that a Pakistani currency crisis is more likely to be a long, drawn-out affair. That will theoretically give the Pakistani government time to reverse course and fix things before disaster truly strikes. But given the political turmoil in Pakistan, it’s anyone’s guess as to whether or not the government will have the capacity to turn the ship around.

4. Lots of foreign-currency borrowing ✔️

Remember, foreign-currency borrowing makes a country more vulnerable to a big crash in its exchange rate. If Pakistani banks or companies borrow in dollars, it means that they have to pay a certain number of dollars back each year. If the rupee falls in value, that makes those dollar repayments much more expensive. And this comes at the worst possible time — right when a country needs to borrow more money to pay its suddenly expensive import bills! Borrowing in foreign currency is thus a dangerous game.

And Pakistan has, unfortunately, been playing this game. Here’s a chart from Bloomberg showing how much dollar debt is coming due in the next few years:

Now this isn’t as bad as Sri Lanka. The amounts of dollar debt Pakistan needs to pay back in the next couple of years are about the same as for Sri Lanka, but its economy is almost four times as large. So this isn’t as catastrophic, but it’s still pretty bad.

Who has Pakistan been borrowing from? Well, a lot of people — the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the IMF, Saudi Arabia, and Japan. But Pakistan’s biggest foreign creditor is China.

Just like Sri Lanka, Pakistan has been borrowing heavily from China in order to fund domestic infrastructure projects, largely as part of China’s Belt and Road scheme. In fact, Pakistan has received more Belt and Road investment than any other country. But as in most countries, the Belt and Road projects have not been an economic success, due to various local factors that the Chinese planners either didn’t expect or didn’t care about. As with Sri Lanka, Pakistan has been left holding the bag.

Pakistan has been slowing down its Belt and Road projects and begging China for debt relief for years now. But while China has allowed Pakistan to roll the debt over, it has not canceled any of the debt yet — Pakistan is still on the hook. This outcome should give pause to all the people who pooh-pooh the danger of Chinese “debt traps”.

Even without China, though, Pakistan has simply borrowed too much in foreign currencies. In a previous post about Pakistan’s long-term growth, I called it a “low-income consumption society” — Pakistan borrows from abroad just to keep its desperately poor citizenry alive.

5. Capital flight ✔️

Capital flight is generally what precipitates a currency crisis. When people try to get their money out of a country, they have to sell that country’s currency in order to do it, which puts downward pressure on the exchange rate. Suddenly everyone is dumping rupees, so the rupee gets cheaper. Pakistan, unfortunately, is highly prone to capital flight. And this time is no exception — people are rushing to get their money out, and the government is trying to implement capital controls to stop them from getting their money out.

6. An exchange rate crash ❓

Capital flight is putting downward pressure on the Pakistani rupee. There hasn’t been as dramatic a crash as in Sri Lanka, but the rupee has lost around 30% of its value since 2021, and the decline seems to be accelerating:

This isn’t yet a full-on currency crisis, but it’s getting there.

7. A sovereign default ❓

Remember, a currency crash makes a sovereign default likely when a country has a lot of foreign-currency debt. Pakistan hasn’t defaulted on its sovereign debt yet, as Sri Lanka has. But Pakistan’s bond yields have skyrocketed to 27%. This means that people are charging a very, very high price to lend Pakistan money. Why? Because people think there’s a high probability that Pakistan will soon default.

8. Accelerating inflation ❓

If a country has a lot of foreign-currency debt that it suddenly can’t afford to pay back, it can default, and/or it can print local currency to pay back the foreign-currency debt (even though this drives the exchange rate even lower). Printing a bunch of rupees would cause high inflation, as it has in Sri Lanka. So far, Pakistan’s inflation rate hasn’t spiked to the degree Sri Lanka’s has, but it’s not looking good:

So to sum up, Pakistan shares a lot in common with Sri Lanka. It doesn’t have a pegged exchange rate, it’s not as dependent on imported food, and it doesn’t have quite as much foreign-currency debt. But the basic ingredients for a slightly more drawn-out version of the classic emerging-markets crisis are there, and there are some indications that the crisis has already begun.

Pakistan’s long-term problems

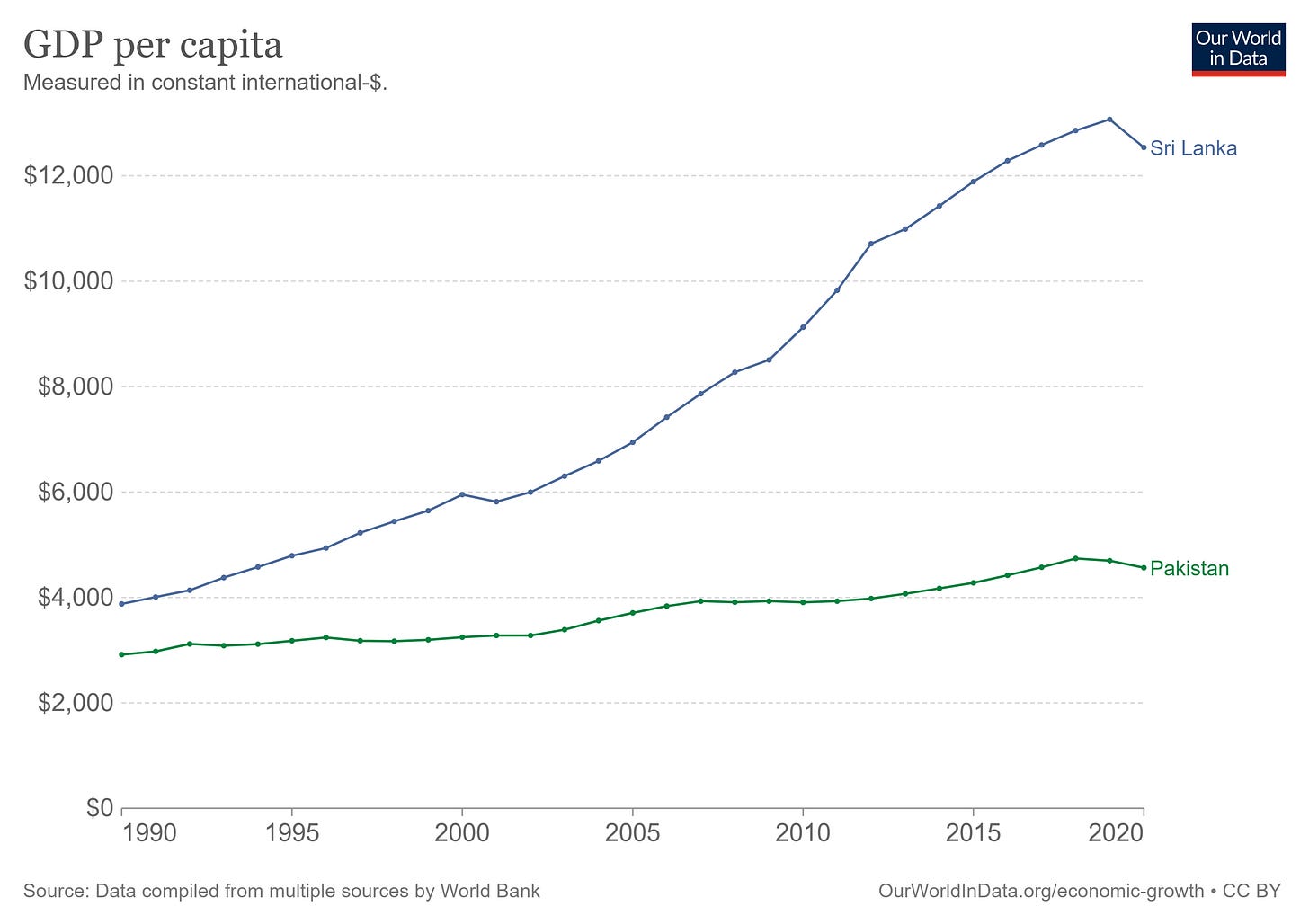

Because Pakistan didn’t peg its exchange rate and didn’t borrow quite as much in foreign currencies as Sri Lanka, it made fewer macroeconomic mistakes than its island counterpart. But in terms of long-term economic mismanagement, it has done much worse than Sri Lanka. No, it didn’t ban synthetic fertilizers — that was an especially bizarre and boneheaded move. But one glance at the income levels of Sri Lanka and Pakistan clearly shows how much the development of the latter has lagged:

Pakistan went from 3/4 as rich as Sri Lanka in 1990 to only about 1/3 as rich today. That’s an incredibly bad performance on Pakistan’s part.

Assessing just why Pakistan has failed so badly for so long is difficult. I wrote a post about it a year ago, but that only scratched the surface:

Basically, Pakistan invests very little of its GDP, so it can’t build up capital over time. Low investment is probably a result of various bad economic policies, but it’s also probably due to political instability — Pakistan frequently alternates between military and civilian control, and civilian administrations tend to be chaotic and fractious (as in the current turmoil). That’s not a very good climate to invest in!

Instead of investing, Pakistan keeps its population on life support with constant external borrowing — from international organizations, from China, from Saudi Arabia, from whoever will loan it money. It uses these loans to fund consumption of basics like fuel. Mian discusses how this has resulted in a perverse fuel subsidy — a pretty common practice for governments that want to keep their populations pacified, but one that Pakistan is particularly ill-equipped to afford.

So Pakistan constantly limps along at the knife-edge of desperate poverty, decade after decade, as generals and politicians fight over who gets to be in charge. Currency crisis or no currency crisis, that is a long-term recipe for disaster.

I was inches away last night from tagging Noah in a tweet to write this exact post, mainly because I hoped he might do the whole South Asian circuit and write a piece on Afghanistan. I was in a Twitter discussion about what's going on with the Afghan banking sector and I realized that some issues, like the implications of the US freezing the assets of the central bank, are over my head.

As it happens I had lunch yesterday with some friends in a rural area of Kabul, at which I was served peaches at three different points during the meal: a little weird although the peaches were very good. Afterwards they took me on a walk through their orchards and I saw what the problem was.

They've got acres of fruit trees and the peaches and plums are fully ripe: you can eat them right off the tree. (Apples and pears not ready yet, I think.) I asked if they were going to hire any labor and they said they would, but clearly most of the crop is going to rot.

They mostly sell in Kabul and they said the main issue was the drop in urban incomes, but Noah's piece made me realize there's another issue as well. Afghanistan also exports a lot of its fruit, mostly to Pakistan, and the fall in the rupee must be hurting sales. (The afghani has also fallen but not as much, so it's strengthened in relative terms.)

I still think it would be great for Noah to write something about this.

Human Capital Flight is also an issue. The lack of medium-term to long-term prospects over many years has meant that large numbers of highly-qualified Pakistanis have voted with their feet.