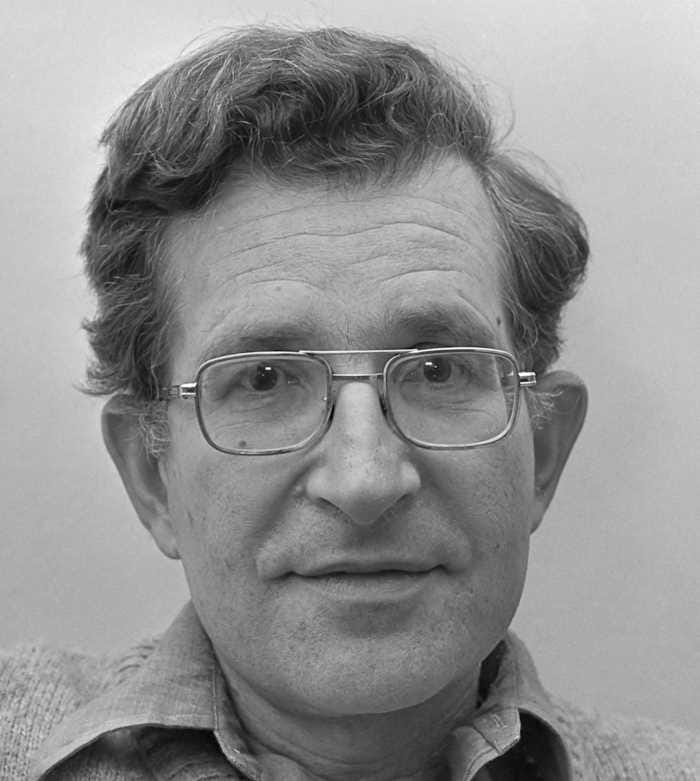

Noam Chomsky and the end of "America bad"

One towering intellectual defined our thinking on foreign policy for a generation. He got a lot of things wrong.

Some outlets are publishing obituaries, but as of this writing, it’s not yet clear whether Noam Chomsky has died. So instead I’ll write an obituary for Chomsky’s ideas on foreign policy, which have had more than enough time to have a deep and lasting effect on how Americans think about their country’s role in the world. Most of that impact, in my opinion, was negative — slightly negative for U.S. national security, but deeply harmful for global stability and human rights.

My first contact with Chomsky was as a child, when my dad — who had been a Vietnam War protester — bought a copy of Deterring Democracy after the 1991 Gulf War. I picked it up off the shelf and read it, and I got the gist well enough. The book is a criticism of America’s support for dictatorial and repressive regimes during the Cold War. That criticism made sense to me. When Bill Clinton ran for President in 1992 and accused George H.W. Bush and his Republican predecessors of “coddling dictators”, I heard a familiar refrain.

But even at the time, something seemed a little off to me about Chomsky’s arguments. In Deterring Democracy, Chomsky excoriates the U.S. for supporting Saddam Hussein in the 1980s, in his war against Iran. He cites Saddam’s use of chemical weapons on Iraqi Kurds as proof of Saddam’s evil. And yet when Chomsky discusses the Gulf War, he dismisses the notion that American foreign policy became more idealistic after the Soviet threat receded. Instead, he argues that the purpose of the Gulf War was to maintain U.S. control over Middle Eastern oil. Obviously oil was part of the reason, but the large number of countries who supported Operation Desert Storm seemed to suggest that international stability was an important goal as well.

When the U.S. and NATO bombed Serbia to protect the population of Kosovo in 1999, Chomsky airily dismissed the stated humanitarian justification for the intervention. Instead, he claimed that the purpose of the intervention was to punish Serbia for not carrying out neoliberal economic reforms:

[T]he real purpose of the war had nothing to do with concern for Kosovar Albanians. It was because Serbia was not carrying out the required social and economic reforms, meaning it was the last corner of Europe which had not subordinated itself to the US-run neoliberal programs, so therefore it had to be eliminated.

Chomsky was also a staunch opponent of the Iraq War a decade later. George W. Bush’s denunciation of Saddam Hussein closely echoed Chomsky’s own — “He gassed his own people!”, Bush thundered, in what could have been a line straight out of Deterring Democracy. But just as in 1991, Chomsky staunchly asserted that America’s claimed reasons for invading Iraq were lies, and that the true purpose of the war was to control oil supplies.

Though Chomsky was right that the Iraq war was a bad idea, it's notable that he refused to give the U.S. any credit for turning on a dictator that he had previously criticized it for supporting. It was not the nature of America’s action in the world that drew his animus — it was the fact of American action itself. Chomsky’s north star as a foreign policy thinker — his fixed belief, around which all of his other beliefs revolved, and to whose contours they were forced to mold themselves — was that America is an Evil Empire bent on world domination. To borrow Imre Lakatos’ terminology, “America bad” was the core of Chomsky’s foreign policy thought, and everything else was an expendable periphery.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Noahpinion to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.