People have been asking me for a while to do a post about my writing process. In fact, I don’t have much of one. I just read some stuff, and then I write what I think about it and hit the “publish” button. Sometimes I outline just a little bit by writing down some section headings at the start of the post, but that’s about it. I don’t even really edit, since it almost always ends up interrupting the flow and sounding clunkier than what I originally wrote.

Anyway, what I think might actually be helpful, or at least interesting, is to write down some writing advice — which also offers some window into why and how I write. Obviously each writer is going to have different advice, so nothing here is gospel.

Write because you need to write

This is the most important thing. Writing because it’s your job — because you need to do it in order to make money — is soul-crushing stuff. I would never, ever want to do that, not least of all because it’s not a lucrative or an easy career. I salute the people who do it out of pure altruism.

I, however, being a lazy and selfish person, write mainly because I need to write. I feel a deep compulsion to comment on what I read and what I see happening in the world. And not just occasionally, but constantly; I can read Twitter for an hour and come up with five ideas for posts, because of that ever-present-burning need to comment on everything.

But why? It’s not because I think my opinions are pure liquid gold, and that I understand everything, and that if only the masses would listen to me, the world would be fixed. There are writers who do have that sort of grandiose self-image, but I’m not one of them. Instead, I write because I need to organize my own thoughts. I need to make sense of the world, and a big part of the way to do that is by writing. And if you’re that kind of person, you should probably at least have a blog.

Write to learn

To make sense of the world, you need to learn about it. And writing lets you do that in several ways.

First, to write about something you should read about it first. One of my PhD advisors told me to read 100 papers for every one paper I write. For blog posts and op-eds the ratio is probably lower (maybe 20?), but the principle is the same. If you aren’t already an expert on something, you won’t become an expert on a topic by reading 20 articles, but you can certainly get a general idea of the topic, the arguments that other people are making, and so on. Read other blogs, read academic papers, read the news, read Twitter.

But in fact, background reading isn’t the only way you learn from writing — sometimes not even the main way. When you put down your thoughts, other people will respond to them. They will have different perspectives. Sometimes they’ll know things you don’t know, sometimes they’ll be totally full of crap. More often, they’ll just be thinking about the issue from a different frame of reference, or applying different ideas and bits of knowledge. Reading responses to what you write — both positive and negative — will help you understand the issue better. And then writing responses back to those people will further hone your thinking.

Humans are not fully autonomous thinkers; we are collective beings. We learn by conversation.

Show other people your writing

When people ask me for help with writing, the biggest problem they have — by far — is that they’re reluctant to show other people what they write. They delay and delay, revising and rewriting, and after all that they’re still embarrassed when they show me what they’ve written. And they wouldn’t dare show it to a friend or coworker.

I’m not going to tell people their feelings of embarrassment, perfectionism, and shyness are bad or invalid. There’s nothing wrong with being embarrassed, perfectionist, or shy. But it does mean you’re probably not going to be a writer.

Showing other people what you write is absolutely essential. It helps you understand how your ideas get through to others. That’s important for learning how to get your point across, but it’s also important for organizing your own thoughts; if what you’ve written is incoherent or flawed or contains dubious assumptions, other people will often catch that. Feedback allows you to improve both the quality of your communication and the quality of your thinking itself.

That said, most of the stylistic advice people give you will be useless. Those people aren’t writers, and if they are, their style of thought and communication is probably pretty different than yours. Instead of obeying people’s advice, watch them — see what ideas they take away, what they understand and don’t understand, etc. And listen to their thoughts about the substance of what you wrote. But if they tell you to rearrange the paragraphs or change the intro or the tone or whatever, just smile and nod and then do what works for you.

“How do you write so much?”

I don’t know. How do you manage to have such an active and fulfilling social life?

Responses, takes, theses, lessons, roundups, and narratives

So now we come to the question of what to write about. Obviously that totally depends on what your field is. But I find that my posts can be divided into a few subcategories:

1) Responses are when someone writes something and you respond to it — either to agree, to disagree, or just to riff off of what they wrote. My ongoing series “Answering the techno-pessimists” posts are all responses to one post that one other blogger wrote! There’s often a temptation to be snarky, aggressive, and dismissive when responding to someone you disagree with, and while that can be fun, it’s not always the most persuasive or effective approach.

2) Takes are when something is happening in the world and you want to give your thoughts on it. For example, I saw Biden unleashing a lot of economic policy proposals, and I wrote a post trying to make sense of them. Remember that you don’t always have to have a take on everything that happens; if you resist the urge to weigh in on every news event, the takes you do make will probably be higher in quality.

3) Theses are when you have an idea about the world that you want to advance. For example, I recently wrote a post hypothesizing that the recent global wave of protests is on some level a response to rising illiberalism. The danger of writing this sort of post is that people tend to be very protective of their theses — once you go out on a limb and declare that This Is How The World Works, any disagreement can feel like a threat to your intelligence, your social status, your very being. You need to resist that, because defending theses to the hilt instead of modifying them in response to new evidence and new ideas is something that makes people less effective at understanding the world. It also, frankly, makes them annoying.

4) Lessons are when you have some piece of expertise and you want to explain it to the world. For example, I wrote a post explaining why Jevons’ Paradox (an economic phenomenon where increased efficiency leads to increased resource use) won’t slow the transition to green energy. In general I think these are always good to write, because if you really have some expertise, then sharing it with others adds value.

5) Roundups are when you gather a whole bunch of arguments, evidence, or other relevant info into one place. For example, I wrote a post summarizing evidence that immigration doesn’t reduce wages, and another summarizing evidence that minimum wage has only a small effect on employment.

6) Narratives are posts where you want to explain how you think about the world, but it’s a gestalt impression rather than a clearly articulated thesis. My post about weeb culture falls under this heading.

There are probably more types than this, and some posts can’t be clearly categorized as one or the other, but hopefully this list helps provide a rough template to think about the purpose of the post you’re writing.

Foxing vs. hedgehogging

I got the concept of “foxes” and “hedgehogs” from Philip Tetlock. In forecasting, “foxes” are people who synthesize a diverse array of information, while “hedgehogs” rely on one big theory. Foxes tend to be better at making actual concrete predictions, while hedgehogs are good at propelling ideas into the discourse.

When I write, I think about what I’m trying to accomplish. If I want to give a reader the best total picture of an issue that I can deliver with a single post, I bring in a lot of different threads, different pieces of evidence, different arguments, etc. On the other hand, if I think there’s some really important central takeaway that readers need to walk away with, I’ll skip the complexity and just focus on the main point. I think of this as foxing vs. hedgehogging.

Which is really just a way of saying that you should think about what you’re trying to accomplish with each post.

Write less than you know

This is an important thing that’s hard to explain. It’s related to the idea, mentioned above, that you should read many articles for every article you write. But it’s actually more than that.

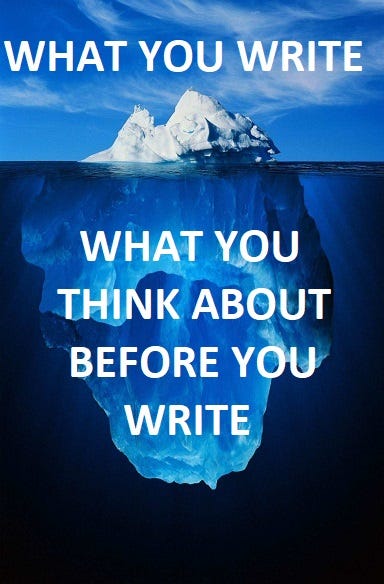

A solid argument is constructed not just of the things you write down, but also of plenty of things you didn’t write down. There’s plenty of background knowledge and context required to decide which facts to include and which not to include; which arguments to address and which to ignore; which aspects of an issue to focus on, etc. etc. That background knowledge can’t all be written down in the post. It’s in your head, not on the page.

Part of this is anticipation of counterarguments. If you want to build the best possible case, you should make sure that you’re capable of addressing the best possible counterargument. This is a form of steelmanning, but it’s not the tendentious act of actually writing down potential opposing arguments; instead it’s something you do internally, in preparation for making your case. Understanding how someone might disagree with or doubt or challenge what you write will help you write something that’s harder to disagree with, doubt, or challenge.

Finally, lots of people are going to doubt that you really know what you’re talking about, and to prove that you do know what you’re talking about might take thousands of words. So you have to drop subtle indications that you have done your homework and that you have the requisite background knowledge to opine on a topic. Doing this is an art that requires long practice — in involves subtle turns of phrase, strategically placed links and citations, or just the structure of the argument itself. It’s your way of communicating to people that although you’re putting your thoughts on a page, you’re not putting all your thoughts on the page.

How to break in

Finally, here’s some pragmatic advice if you aren’t already a well-known writer and you want to become one. The first thing you have to do is to figure out how to add something novel to the discussion. This isn’t necessary for being a good writer, but it is necessary for being a successful writer. You can teach people about something they don’t understand. You can come up with fresh and exciting takes. You can rehash old stuff but with a writing style people enjoy. There are lots of ways to add value.

One thing you can do, which works for a lot of people but which I don’t recommend, is to get noticed by aggressively criticizing famous and influential people in an area. This is often effective for breaking in, because fights attract attention, because criticizing ruling orthodoxy is new and different almost by definition, and because the famous and influential people can sometimes be baited into trying to punch down (which almost never works out well for them). In fact, I did this quite by accident, simply by being a pissed-off grad student whose angry blog got infinitely more attention than he had anticipated. But — take it from me! — there are big downsides to this approach. First, you make enemies. Second, being a jerk becomes your shtick, and before you know it you’re doing it professionally. Third, as they say, if you come at the king, you best not miss; the internet is littered with the forgotten posts of bloggers who tried to snark on smart people and just ended up looking like dorks.

I should also note that there are some very bad and unethical ways you can break into the discourse — spreading disinformation, attaching yourself to unsavory political movements, pumping financial assets, and so on. Don’t do these things. You only have one life; don’t waste it being a schmuck.

After breaking into the discourse, you’ll need to grow your audience. I have two basic pieces of advice on how to do this. First, just like a startup trying to grow its customer base, look at your metrics and your feedback. Figure out which kind of people are interested in things you write. Play around with new topics and new formats to see if you can find hidden pockets of interest (and just for fun, of course). Look at how people react to the things you write, and iterate and improve.

And second, get to know the other writers in the field. Writers are a professional community, and it pays to be part of that community. Follow them on Twitter, go out for drinks, whatever. If they don’t give you tips and ideas or promote your stuff or make other useful introductions, at least you’ll make some friends!

Anyway, that’s about all the writing advice I can think of. Hope that helps. Oh, one more tip: Don’t spend too much time trying to think of a pithy concluding sentence.

Wow! Such pure Noah Smith thought! Thank you!

Good stuff, thanks. As primarily a writer of occasionally cogent emails I wish I had your apparent talent for leaving stuff out without doing much editing. My initial cut almost always rambles and it is on my own review I see that I might actually have a valid point of view in there somewhere. So then chopping away at it to reveal said argument is extremely valuable. More power to you if you write close to a finished draft the first time!