No, the U.S. is not "a poor society with some very rich people"

We're a rich society with some very poor people.

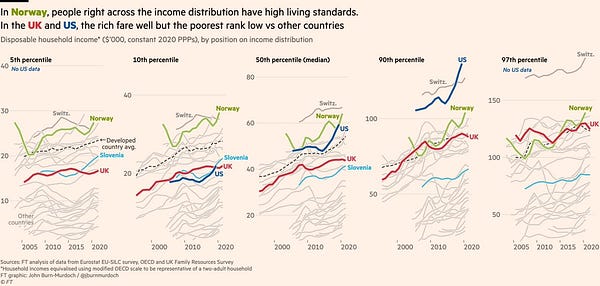

John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times is one of my favorite economics journalists. But when he describes the U.S. as “a poor society with some very rich people”, he’s just not right:

This inaccurate description of the U.S. — which comes from the headline of the article itself, and is repeated in the final sentence — is highly appealing to a lot of people. Many Americans resent the (very real) concentration of wealth at the top of the distribution, and many are (quite rightfully) still upset about decades of slow income growth. And some outside the U.S. resent the smug chauvinism with which some Americans trumpet that their country is the greatest in the world. So it’s little surprise that the tweet above went viral.

And Murdoch is certainly right when he notes that America is a more unequal society than most other rich countries, and that we should focus more on redistributing income to the people at the bottom. I strongly agree with the following:

To be clear, the US data show that both broad-based growth and the equal distribution of its proceeds matter…Five years of healthy pre-pandemic growth in US living standards across the distribution lifted all boats…But redistributing the gains more evenly would have a far more transformative impact…The growth spurt boosted incomes of the bottom decile of US households by roughly an extra 10 per cent. But transpose Norway’s inequality gradient on to the US, and the poorest decile of Americans would be a further 40 per cent better off while the top decile would remain richer than the top of almost every other country on the planet.

But by focusing only on the rich and the poor, Murdoch leaves out something incredibly important — the middle class. Of course it’s important to uplift the people at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. But most people are not at the bottom of the ladder. That’s true by definition. And when we look at how Americans in the middle of the distribution are doing, we see that America is not a “poor society” at all — in fact, it’s one of the richest on Earth.

America’s middle class has higher living standards than almost any other country’s middle class

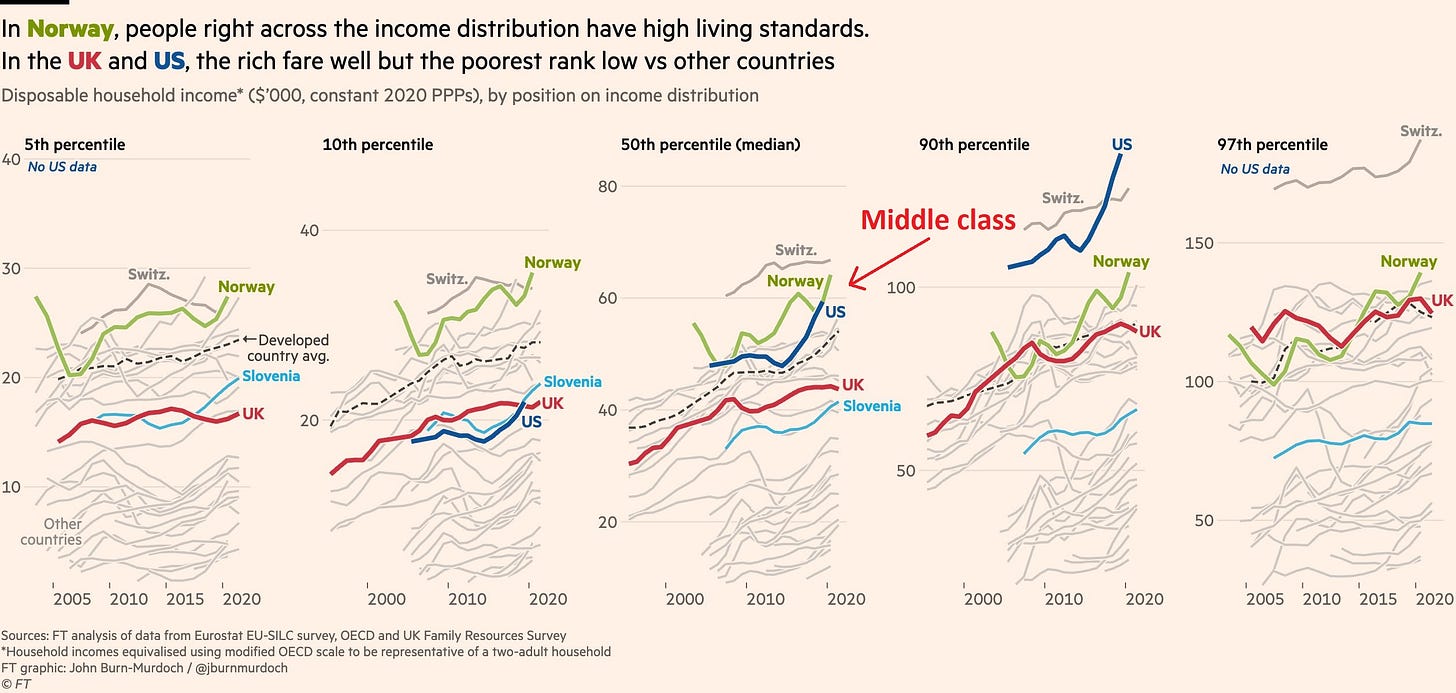

First, let’s take a look at the FT’s own graph. I’ve helpfully labeled the position of the U.S. middle class:

It’s clear from looking at that dark blue line that the median American has a higher income than the median resident of almost any other country on Earth. It looks like the U.S. is slightly behind Norway, but in fact this is an illusion — the U.S. data only goes through 2019, while the data for other countries goes through 2020. If you look at the spot where the U.S. curve touches the Norway curve, it’s clear that the U.S. median was slightly above Norway in 2019, and behind only Switzerland.

In fact, if the U.S. data for 2020 was included on the graph, we’d see another big jump in disposable incomes, since pandemic relief boosted these quite a lot:

Also, the FT’s data — which is proprietary — seems to be a little different than other sources. Here, via Ryan Radia, is a chart showing the OECD data for the most recent years available:

This should be the exact same thing that’s shown in the “50th percentile” panel of the Financial Times graph — median disposable household income at purchasing power parity, adjusted for household size. But you can see there’s a slight difference — the FT has Switzerland’s 2018 number ahead of the U.S.’ 2019 number, while Radia finds the opposite. (This may be because Radia includes some government transfers that the FT doesn’t. When you measure how unequal a society is, you should always use a measure that includes the government’s existing efforts to reduce inequality!)

The FT’s chart also leaves out every percentile between 10 and 50, and between 50 and 90. Here’s a more complete picture of the distribution:

Some people argue that because European countries buy health care for their citizens via the government — which is not counted in disposable income — that it’s not fair to use disposable income as the comparison measure here. But this isn’t right. The U.S. has a relatively low percentage of out-of-pocket health spending — our employers and our government pick up most of the tab. In fact, when we look at “adjusted disposable income”, which includes the value of government services like health care, we find out that the U.S. comes out even more ahead relative to other countries.

In any case, whichever numbers we use, it’s clear that the median American earns more income than the median resident of almost any other country on the planet.

And it’s worth noting that higher average incomes partially cancel out the deleterious effects of higher inequality. A good measure of inequality is the relative poverty rate — the percent of people living at or below half of the median income. In the U.S., this number is higher than for other rich countries — in 2019 it was 17.8%. That means that someone at around the 18th percentile of income in America in 2019 — a working-class person on the edge of being considered poor — lived in a household making $21,400 a year. That’s about the same as the median income of households in Japan, and about 84% of the median income of households in the UK.

In other words, a working-class American on the edge of poverty makes as much as a middle-class person in some rich countries.

Beyond aggregate statistics

Just to drive this point home, let’s look beyond aggregate statistics at some of the actual goods and services that Americans enjoy.

For example, let’s look at housing. On average, Americans have more living space per person than pretty much anyone else, with only Australians and Canadians coming close:

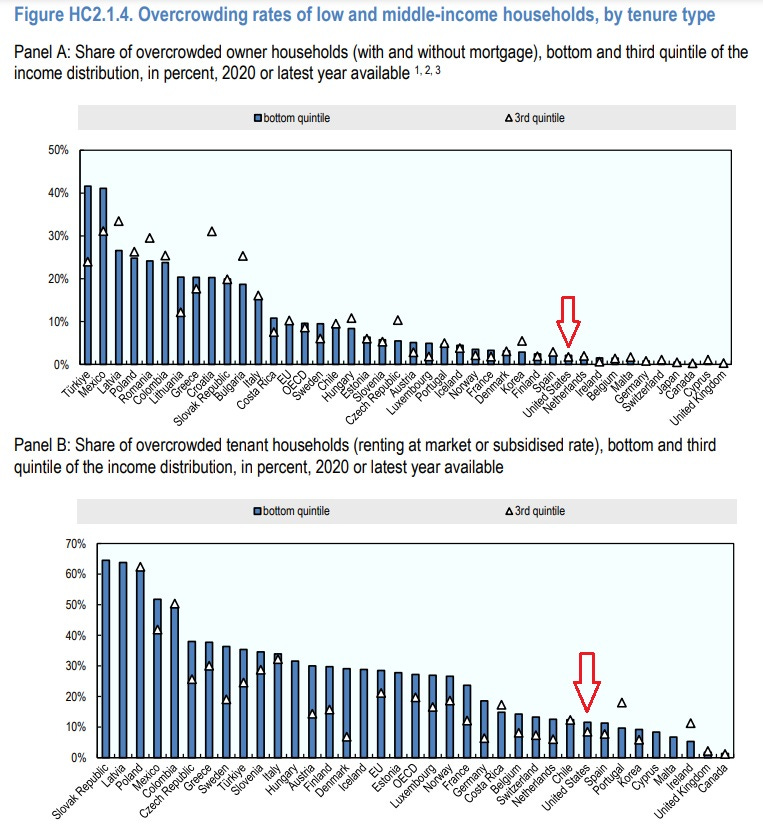

Now, that’s an average, but U.S. data shows that average and median track each other pretty closely — there aren’t a few giant mansions skewing the average here. In fact, the U.S. has a lot of housing space all throughout the distribution. Despite our high income inequality, we have one of the lowest rates of overcrowding among lower-income renters in the OECD:

In addition to their big houses, regular Americans have lots of cars:

This is, again, an average rather than a median, but it’s highly unlikely that a few rich people with thousands of cars are skewing the average here. The typical American is simply quite likely to own a car. In fact, American households are more likely to own a car than households in any other country.

Now, the sprawling suburban single-family-house-and-a-car development pattern is not my personal favorite, and it’s certainly not the best for the environment. But Americans have continuously moved out to the suburbs for many decades, even during the supposed “urban revival” of the 2000s and 2010s. The trend is continuing. Given the choice of where to live, Americans choose big houses and cars. That choice represents material wealth. Nor do Americans pay for this choice with long commute times; the OECD finds that Americans spend less time commuting to work or study than people in almost any other rich nation.

The U.S. also consumes more meat per capita than any other country. That’s not necessarily healthy, and probably contributes to our high obesity rates. Nor is it good for the environment. But it does represent a lifestyle choice — people across the world tend to eat more meat as they get richer. (Again, this is an average, not a median, but it’s unlikely to be skewed by a few rich people eating hundreds of times as much meat as the middle class…food just doesn’t work like that!) The same pattern holds for electricity consumption; Americans use more than almost anyone, except for people in a few rich countries with very extreme temperatures.

Health care is the one exception to the pattern — the U.S. consumes a lot more dollars’ worth of health care than other countries, but only because we pay a lot higher prices. In terms of use of health care services, we’re pretty average.

In any case, it’s very difficult to look at a country where the typical person lives in a larger house, is more likely to own a car, eats more meat, and uses more electricity than people in other rich countries, and to conclude that this is “a poor society”. All of these indicators fit with what we see from aggregate statistics, as well as anecdotes and stereotypes — the typical middle-class American lives a more lavish life than their counterparts in Europe or other rich nations.

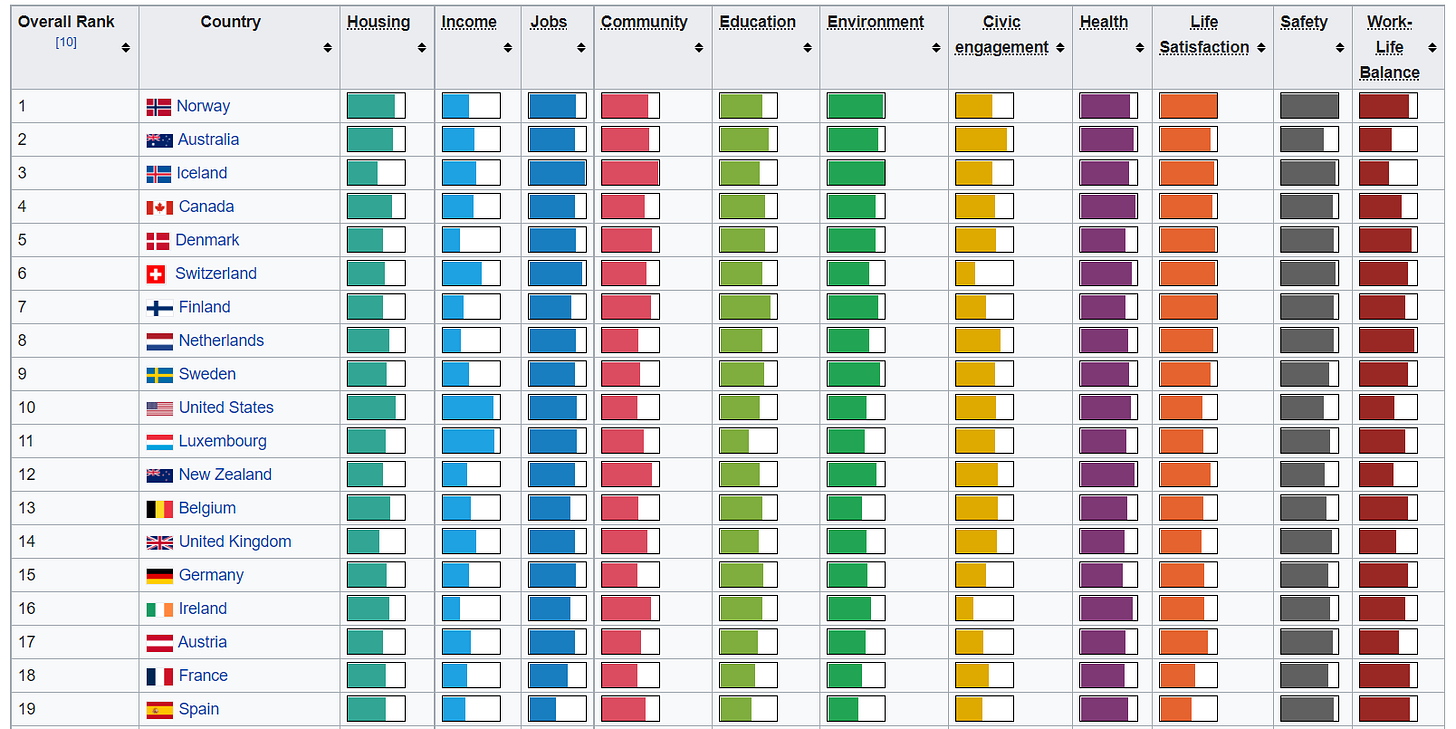

It’s also worth saying a few words about quality of life here. In a post back in July, I noted that in many respects, Europeans enjoy a nicer quality of life than Americans do — less crime, lower obesity rates, and slightly fewer working hours. But in the OECD’s Better Life Index, the U.S. comes out a respectable 10th, behind Canada, Australia, and the Scandinavian countries, but above most of Europe and all of Asia.

Don’t forget the middle class!

It’s incontrovertibly true that America is more unequal than most other rich nations. We have a very real poverty problem; the bottom 10% of our population suffers much more than they ought to. And yes, more redistribution from the top would help to solve this, though that’s far from the only thing we need — in order to create real abundance for the poor and working class, we will have to increase the supply of things like health care and child care, as well as improving public safety and public health.

But this very real problem should not make us forget the importance of the broad middle class. The people between the 10th and the 90th percentile of the income distribution make up the vast majority of the population, the labor force, and the electorate. It is their economic situation, not that of the poor or the rich, that will define the country’s mood.

And the economic situation of the broad middle of the American class structure is simply better than that of their counterparts in other rich countries. The American middle class has plenty of problems — declining upward mobility, gun violence, alcoholism, opiates, family breakdown, and social divisions. But they are not poor people, by any nation’s standards. And to characterize them as such — to imagine that the problems of the American middle class can be largely fixed by redistributing the income of the 90% — is a distraction from the real problems and the real solutions. Yes, redistribution is good, and yes it can help solve America’s high poverty rate. But for the social ills that plague the middle class, the solutions we need will not be so simple.

I think the reason you see dumb takes like this is because it's harder to say "the USA, while a very rich country, has major issues with inequality and the provision of services for the poor, but overall generates a lot of wealth for it's people". Much easier to say dumb shit like "the USA is a poor country with rich people"

Glad to see you mention home sizes -- the graphic here https://www.thezebra.com/resources/home/median-home-size-in-us/ (since 1980) is pretty stunning. Americans need big enough spaces to eat their meat portions.